Lover’s Eyes:

Eye Miniatures

from the Skier

Collection, 2021

Ed. Elle Shushan;

essays by Graham C. Boettcher,

Stephen Lloyd, and Elle Shushan.

Photography by Nik Layman.

280 pages

Giles Ltd.

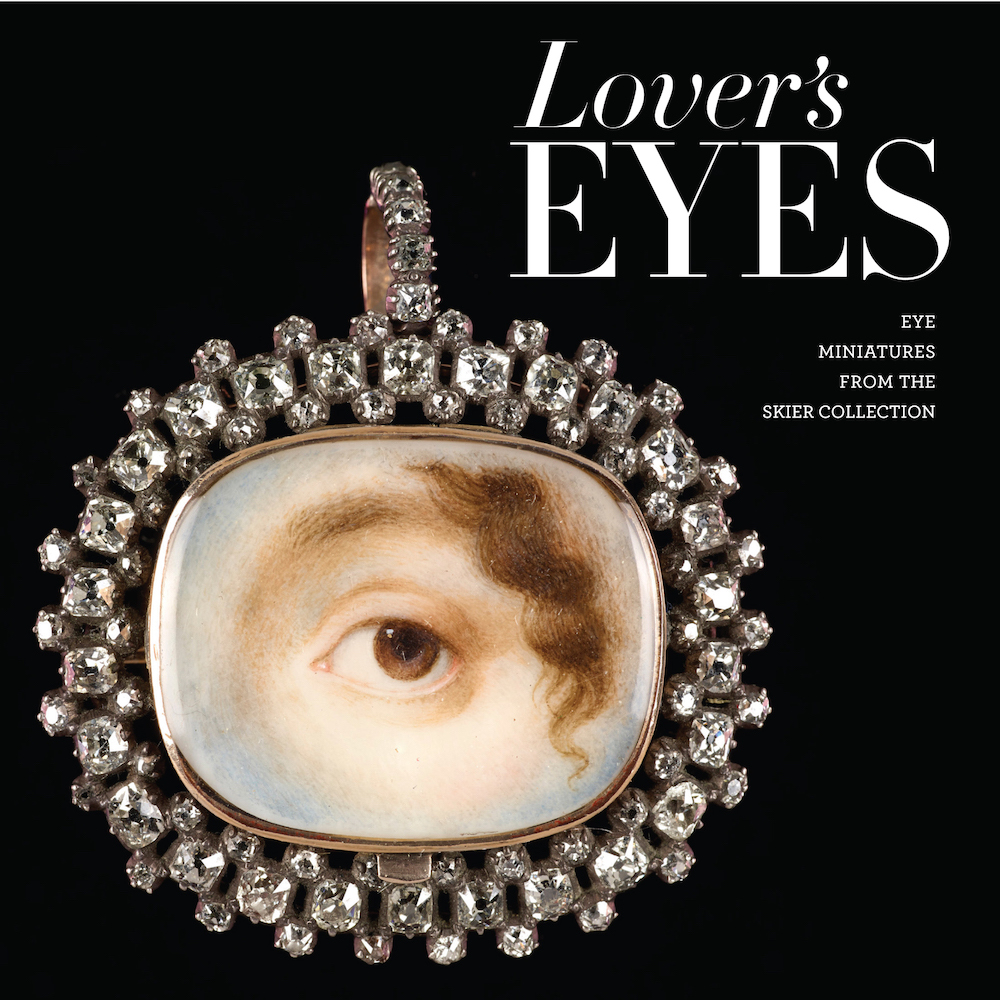

Lover’s Eyes, a new catalog on eye miniatures, lets us peer at one of the most extensive private collections of these weird and wonderful 18th- and 19th-century works—most of which stare right back.

Eye miniatures were briefly in vogue in England at the end of the 18th century, their popularity inextricable from the story of the Prince of Wales’ love for Mrs. Maria Fitzherbert and his commission of several of the tokens. As always, the truth is a bit more complicated than the romance, and dealer Elle Shushan provides a fair overview of the trend’s history, situating the works within the traditions of portrait miniatures and sentimental jewelry. Stephen Lloyd provides further detail on court artist Richard Cosway, the best-known painter of the form. Cosway actually went unpaid for his trend-setting eye miniatures: rather than risking offense to his royal client by insisting on invoices, he leveraged the prestige of royal patronage into the rest of his business (“working for exposure” is nothing new).

Typically painted in watercolor on ivory, eye miniatures were often set in intimate pieces like bracelets, brooches, pendants or rings. The catalog also contains several boxes and a unique wallet, while the essays cover other exceptions that prove the rule—like the oddly surveilling 1840s eye miniature that was set in a mantelpiece. Essays on the symbolic languages of gems and flowers, which were often included in the miniatures’ settings or painted alongside, show much potent meaning could be contained in one tiny object and in how many ways they communicated to their viewer or recipient.

Book cover

Most interesting was the essay on the afterlife of eye miniatures, a little-studied field: Graham Boettcher adds much with his survey of how later artists took inspiration from the trend. Magritte and Dali brought Surrealist takes into view; some might add the oversize eyes of the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough commissioned for the ceiling of Blenheim Palace in 1928 to that category. Boettcher also explores how contemporary artists have played ironically with the form’s conventions, from making miniatures of the eyes of famous works—a game of “spot the painting”—to creating animal eye miniatures or commemorating other fragments of the body. Fatima Ronquillo depicts people of color with and in portrait miniatures, often combining the format with the tradition of Mexican milagros, or devotional charms; her pensive works have the added effect of highlighting the racial homogeneity of the trend’s earlier subjects.

Flipping through the vast collection of eyes, I was paradoxically struck by the individuality of each one, down to the finest detail of facial features and settings. Despite—or because of—the fact that most of the eyes remain anonymous, their gazes hold endless fascination. In the context of distance and disconnection, people often look for objects that can make them feel close. We’re more likely to send a selfie than an eye these days. But Lover’s Eyes shows that time has not changed the creative variety of ways we try to look at and see one another.