Despite their welter of contrivances, and their aesthetic dependency on such elaboration, Amir Fallah’s paintings maintain a deep, charming and abiding sense of mystery. Like so much current painting that conflates figurative and abstract elements—and like so much painting that self-consciously crawls or explodes off the canvas onto the supporting walls —Fallah’s art makes an involved display of its manifold and heterogeneous elements. Unlike so many of his peers, however, Fallah makes such pictorial spectacle work, visually and theatrically—not simply through formal cohesion (which he is often willing to diminish or even risk foregoing), but through the image’s own visual drama. Fallah’s current work in effect embodies the “performance” itself, the stage sets, and the hall housing the audience.

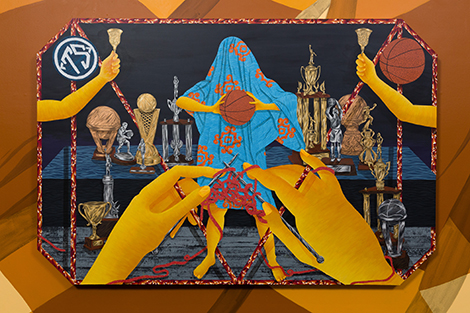

Fallah is an aesthetic maximalist, filling his canvases—and the walls on which they hang—with busy patterns, bright colors and unobtrusive but persistent touches of trompe l’oeil. As restless as fireworks, they refuse to sit still long enough to behave as pictures; but pictures—or at least presences—constitute the conceptual as well as optical nucleus of Fallah’s entire approach. The images, after all, have been assembled conceptually even more than they have visually: the back stories to the installations overall as well as to their components reside in the process of assembly. The paintings in “From the Primitive to the Present” (all works 2015), Fallah’s Chinatown installation, were all devised as imaginary portrayals of members of a family whose belongings he had found and purchased (not by accident) at a North Hollywood estate sale. Everything from fabric patterns to old photographs to clothing to journals found their way (sometimes literally) into these paintings. “Perfect Strangers in Santa Monica” (all works 2014-15) also comprised a number of constructed “portraits,” although this time, since the painting-project was conducted in collaboration with local college and K-12 students, the paintings resulted from the active input of the subjects and their relatives and friends. The core of the installation was a platform-mounted, igloo-like enclosure inside which four eccentrically shaped, in fact rather heraldic paintings hung. The gallery’s own walls displayed montages of family photos and other personal ephemera, the kind(s) on which Fallah depends to “build” his presences, this time brought to him by his collaborators and given their own berth, and dignity, in the overall presentation.

A 3D display anchored the heart of “From the Primitive to the Present” as well, but here Fallah set out discrete objects cast in multiple from his estate-sale cart-away. Coffee cups, crucifixes, construction hats and other objects sat drenched in the same earthy grays, browns and yellows that predominated throughout the show. The color scheme for “Perfect Strangers” was darker and more enveloping, a soft nighttime to the downtown installation’s harsh day. Such a contrast hinted at a deliberate binary relationship between the two exhibitions. Resulting from different processes, they said different things, but spoke to each other from either end of town.