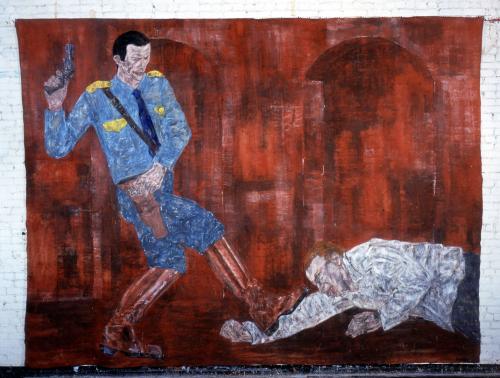

It’s been a tumultuous week in Los Angeles; and for a change, we can’t blame it entirely on the Putin-wannabe currently installed in The White House or his cronies and GOP enablers – notwithstanding the fact that he happened to blow into town this same week to pick a...