It was interesting to walk through the Jasper Johns exhibition, Something Resembling Truth, only a couple of days after my first look at Mark Bradford’s new paintings at Hauser & Wirth. Bradford’s paintings marked something of a departure for him – continuing to move steadily away from the grid-like mappings that were once seemingly a foundational element to his work, and towards an almost centrifugal style of composition – ever more richly layered and textured, spatially and almost temporally complex – they hold the viewer’s attention and pull us right in into their vortices. Even the titles hinted at the fresh narrative charge and density of some of these paintings. You felt a roller-coaster tug as your eye followed (and fell into) some of the more vivid, primary passages; and – well, we weren’t in Kansas anymore….

And what, we might ask, would that have to do with Jasper Johns? Not necessarily all that much – though a friend of mine saw echoes of Johns’ more colorful and tightly meshed ‘between bed and clock’ cross-hatch paintings in a few of Bradford’s still more tightly wound, thickly (and colorfully) embedded whirlwind passages. Although both share some affinity for cartographic approaches and strategies, the common ground between the two artists amounts to nothing less than consciousness itself. For all his cool, his emotional disengagement, and will to neutralize or complicate the gestural or more expressive passages in any given work, Johns is fairly transparent about his process – the role of hand, brush, color/palette, device and external objects or references incorporated into the work. That we may still find an element of mystery in some of these works of almost methodical de-mystification is a sublime irony. There’s as much modesty as ambition to the way both artists approach the mapping of consciousness. With Johns especially, we’re made acutely aware of how time impinges upon the artist’s domain. There’s a kind of internal geo-positioning at work in Johns’ art that always returns us to the locus of its germination – the studio. (Bradford in turn seems to check the impulse toward infinite extension with a kind of internal deconstruction.)

The story (his own) about Johns dreaming himself painting an American flag and, upon awakening the next morning, assembling his materials and painting that iconic painting, long ago entered the folklore of contemporary art history. To this day, I’m not sure if I really believe it. It might have been an American flag he saw in that dream; but, by Johns’ own words, it was a dream. Dream images may bear some resemblance to the corresponding objects in waking life – but as often as not, they indicate a phenomenon at some remove from the corresponding physical actuality. Revisiting these paintings – and I don’t mean simply the white or gray or secondary inversions (e.g., green and orange), I can’t help but think that this ‘dream image’ references not only the commonplace object (though in this instance, one with considerable political baggage), but an underlying restatement of its spirit and inspiration. Moreover, Johns’ process (or what we know of it) is fairly deliberative. Although a facile and prolific draughtsman, Johns does not arrive at his chosen subjects and motives randomly.

As a literal representation, Johns is ‘painting over’ the American flag, effectively neutralizing its symbolic values, painting them out. It’s also something of an existential inquiry: how are those values arrived at, constructed? There is also the matter of its design scheme – its compartmentalization (or for that matter any flag’s design: the rectangular convention, the color blocks, one perhaps more dominant, in alternately vertical or horizontal orientation, discreet national symbolic insignia), its colors, its striping. (And of course, the U.S. flag’s design and creation carries its own baggage of history and legend.)

As a literal representation, Johns is ‘painting over’ the American flag, effectively neutralizing its symbolic values, painting them out. It’s also something of an existential inquiry: how are those values arrived at, constructed? There is also the matter of its design scheme – its compartmentalization (or for that matter any flag’s design: the rectangular convention, the color blocks, one perhaps more dominant, in alternately vertical or horizontal orientation, discreet national symbolic insignia), its colors, its striping. (And of course, the U.S. flag’s design and creation carries its own baggage of history and legend.)

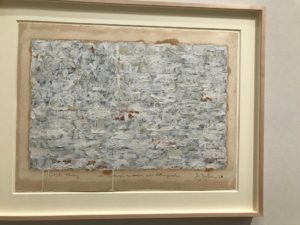

Setting to one side the American mythology, Johns is compartmentalizing, too. This is a kind of landscape – ground (and foreground), horizon line or lines – always shifting with the changing light, and star-filled sky (or at least that corner we’re claiming of it). Call it a landscape fit for the nascent Television Age (or the Kefauver hearings? – recalling that Johns is a transplant from South Carolina; New York is still fresh for him). The flags are still something to see – possibly because they have bled off some of their iconic power as art historical legacies. We can take a moment to appreciate what Johns made of those stripes with a mix of newsprint and encaustic – its dramatic materiality. It’s already an exaggerated kind of mark-making. He’s tearing it up a bit – these are turbulent fields. The ‘expression’ is effectively contained. ‘Gesture?’ – we’re silently prodded. ‘You mean the flag isn’t enough?’

The ‘dreamwork’ here amounts to a kind of actualization – a very different kind of ‘action painting’ – engaging the subject not through its image but through the thing itself, merging subject with object; moving still further away from depiction to deconstruction. Simultaneous with effectively painting over the flag, he dramatizes its materiality, shredding the surface (or certainly the newspaper and encaustic that merge with its pigments), as if to complicate and interrogate its valuation color bar by color bar. No artist is entirely free from history; and however cool or detached he might be professionally, Johns is no exception. The beginning of the Television Age also marked a new consciousness of the country’s precarious social fabric and its complicated and frequently corrupt political culture. Johns career begins at a moment when the entire American culture is examining its values.

This is not to call Johns’ work political in a conventional sense, but simply to underscore its resonance with both New York School painting and art-making and the Zeitgeist at large. Everywhere in his early work, Johns is examining valuation and the tools and devices we use to shape, construct and translate it. (It could almost be called a ‘cross-examination’: consider the early “Construction With Toy Piano of 1954” (not in this show) in which Johns places his object ‘mapping’ beneath a 12-key toy piano keyboard – especially interesting in that the value progression here encompasses tonality – but deliberately complicates pitch intervals by stenciling numbers over them (a fragmented seven-note scale – presumably omitting half-tones).) It has been remarked (and by Johns himself) that Johns sought subjects/motives from among objects or signs that went essentially unnoticed, whose conventional meaning was immediately grasped and accepted without question. That is certainly part of it: how better to take the measure of a culture’s values? But I think Johns moves rapidly from that initial impulse to a much more deliberative process.

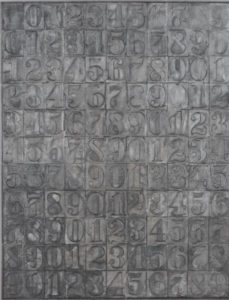

Johns enjoys a certain notoriety for his reticence about discussing his work or process. But whether we examine the work thematically or chronologically, it’s hard to see why it’s much of an issue. He’s fairly straightforward about it: to paint over (or wash over – his dense pencil/graphite washes take on the quality of a rubbing); to interrogate value by means of virtually mathematical operation – addition, subtraction, multiplication, even (less successfully) division; neutralizing gesture and ‘expression’ to expose and define meaning – or ‘something resembling’ it. Naturally he is drawn almost immediately to the domain of symbolic meaning and the systems devised to organize it. He’s fascinated with the notion of their simultaneous arbitrariness and internal logic – and subjects them to the arbitrariness and logic of his own contrapuntal method. The Roman alphabet and Arabic decimal order are variously gridded and compressed. A ‘transparent’ “0 through 9” may be both muddled and disordered (not unlike that toy piano keyboard). Which asserts primacy? – the ‘3’, the ‘5’, ‘1’, ‘4’ or ‘9’? It’s just a hunch on my part – although I think there has been some discussion of it in critical or academic discussion of his work – but I’ve always thought some of this (relatively early) work indirectly influenced by Joseph Cornell and his “Medici Slot Machines.”

Johns enjoys a certain notoriety for his reticence about discussing his work or process. But whether we examine the work thematically or chronologically, it’s hard to see why it’s much of an issue. He’s fairly straightforward about it: to paint over (or wash over – his dense pencil/graphite washes take on the quality of a rubbing); to interrogate value by means of virtually mathematical operation – addition, subtraction, multiplication, even (less successfully) division; neutralizing gesture and ‘expression’ to expose and define meaning – or ‘something resembling’ it. Naturally he is drawn almost immediately to the domain of symbolic meaning and the systems devised to organize it. He’s fascinated with the notion of their simultaneous arbitrariness and internal logic – and subjects them to the arbitrariness and logic of his own contrapuntal method. The Roman alphabet and Arabic decimal order are variously gridded and compressed. A ‘transparent’ “0 through 9” may be both muddled and disordered (not unlike that toy piano keyboard). Which asserts primacy? – the ‘3’, the ‘5’, ‘1’, ‘4’ or ‘9’? It’s just a hunch on my part – although I think there has been some discussion of it in critical or academic discussion of his work – but I’ve always thought some of this (relatively early) work indirectly influenced by Joseph Cornell and his “Medici Slot Machines.”

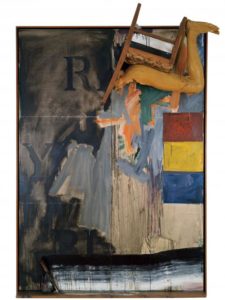

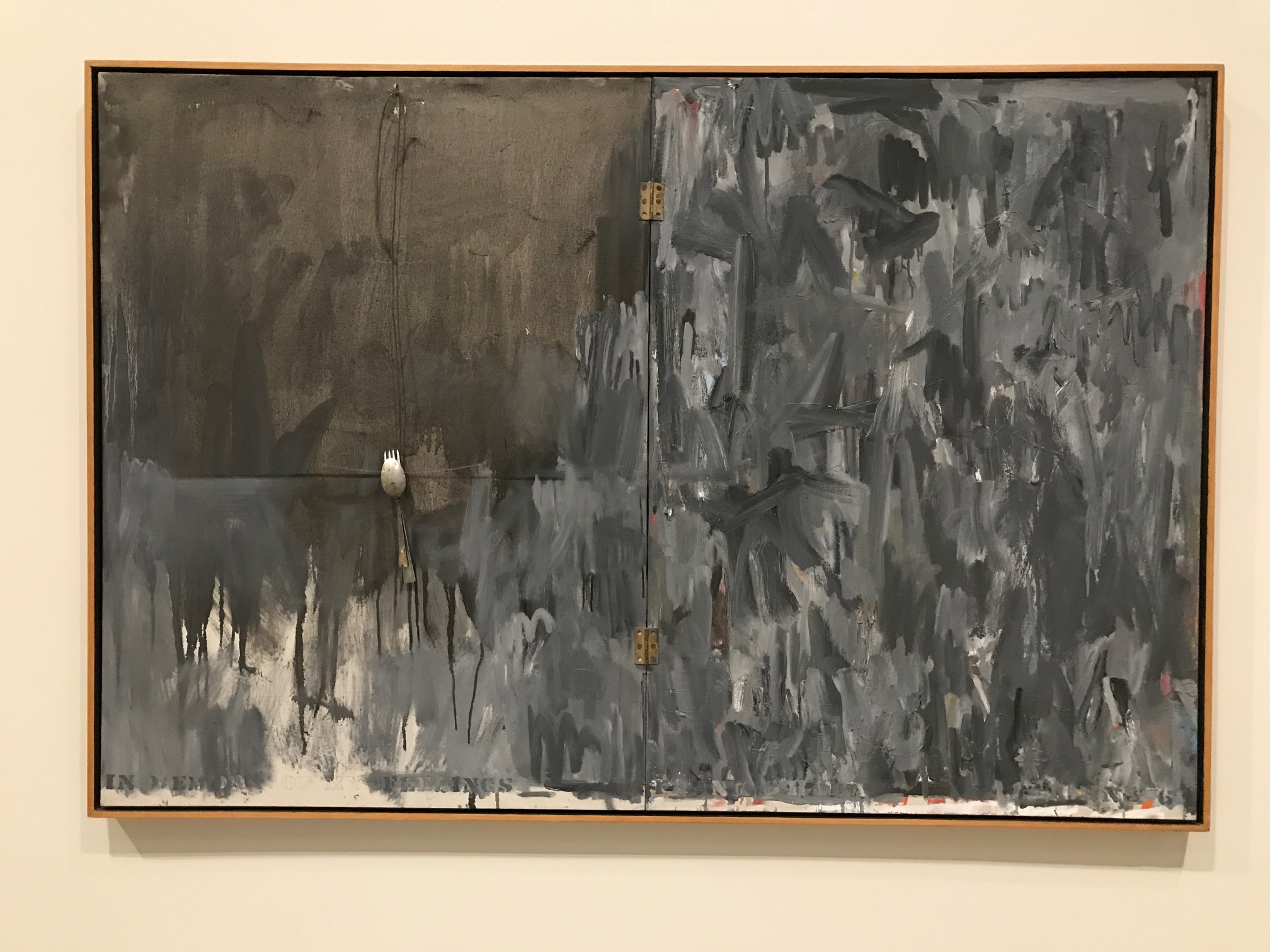

How better to neutralize gesture or expression than by machine-processing it? This isn’t exactly the direction Johns is taking his process – the hand is always in evidence, however restrained. But it’s hardly accidental that not long after these variously chromatic, painted-over, gray-washed, and stenciled arrays, he begins to trace or actually insert tools and assorted ‘devices’. At the same time, Johns seems intent upon differentiating some of these devices, tools (accessories? – and still later, ‘souvenirs’) from the stuff of ‘collage’ – consistent with his painting-over/making-over process. These are extensions – a repertoire Johns eventually extends to his personal anatomy (e.g., “Watchman,” 1964); or still earlier, moving beyond the notional ‘rubbing’ to an imprint of his own skin (e.g., “Skin With O’Hara Poem,” 1963-64 – there are several iterations of this subject, but this lithograph is one of the most moving – and who said Johns was never emotional?). Up against the limits of time, Johns seems to be geo-positioning – fixing the moment squarely in his studio. More than any other mechanical bit encompassed by this painter’s ‘toolbox,’ the hinge seems most crucial. It’s also noteworthy that – hinges, hooks, rulers, stretchers or plaster casts notwithstanding – Johns resists calling any of these works ‘combines.’ I don’t think it’s accidental that it was around this time that Johns and Robert Rauschenberg split (though I believe they continued for some time to collaborate on their display advertising business).

How better to neutralize gesture or expression than by machine-processing it? This isn’t exactly the direction Johns is taking his process – the hand is always in evidence, however restrained. But it’s hardly accidental that not long after these variously chromatic, painted-over, gray-washed, and stenciled arrays, he begins to trace or actually insert tools and assorted ‘devices’. At the same time, Johns seems intent upon differentiating some of these devices, tools (accessories? – and still later, ‘souvenirs’) from the stuff of ‘collage’ – consistent with his painting-over/making-over process. These are extensions – a repertoire Johns eventually extends to his personal anatomy (e.g., “Watchman,” 1964); or still earlier, moving beyond the notional ‘rubbing’ to an imprint of his own skin (e.g., “Skin With O’Hara Poem,” 1963-64 – there are several iterations of this subject, but this lithograph is one of the most moving – and who said Johns was never emotional?). Up against the limits of time, Johns seems to be geo-positioning – fixing the moment squarely in his studio. More than any other mechanical bit encompassed by this painter’s ‘toolbox,’ the hinge seems most crucial. It’s also noteworthy that – hinges, hooks, rulers, stretchers or plaster casts notwithstanding – Johns resists calling any of these works ‘combines.’ I don’t think it’s accidental that it was around this time that Johns and Robert Rauschenberg split (though I believe they continued for some time to collaborate on their display advertising business).

For Johns, every subject is a device – an activation or intervention in a meta-morphological field of phenomena or objects variously freighted or depleted of meaning or significance. In this occasionally arbitrary universe, there’s really nothing arbitrary about Johns’ seizing upon targets, or more specifically, the ‘bullseye’ target – a departure from the rectilinearity of the subjects/devices that coincide with or immediately precede them. (One might consider the various celebratory decorative trimmings that are extensions of flags and pennants – e.g., the swags and bunting draped everywhere in national holiday observations.) Beyond its shape, its primary color scheme and discrete concentric zones circling the bullseye, it’s a device that can be extended axially or otherwise in any number of directions. It’s a Norse shield; it’s the eye itself; you may ignore it, but not if you’re aiming at it – and what exactly are we aiming at? We’re presented with an entirely different order of progression here; it’s not something we can relate to passively; and there’s an entire history to it, too – a mythology, if you will.

This is what brings us back to Johns – and a style, technique and vision that, notwithstanding his stylistic, painterly, and proto-Conceptual antecedents (Duchamp principal among them), might just as easily be compared to the zero-degree prose and drama of writers like Gide and Beckett. Micro-mapping his consciousness on the broadest platform (even within the confines of his studio), Johns pulls the viewer to a place underlying our apprehensions, expectations, and implied consent – the embedded mythologies that inform or effectively neutralize our perception and/or relationship to the subject. Johns dredges this up in a moment of extended duration. I thought the show’s title managed to sum up this aspect of Johns’ work rather succinctly (though I’m not completely sure that’s what they were aiming for). It’s not about a ‘truth’ tested, or subjected to analysis or established by proof; it’s about something we give implicit consent to. As in (for the kids out there) ‘this is becoming a thing’ – a new reality – although I’m not sure even this exactly does justice to Johns’ process. And it’s not as if Johns never contradicts himself or complicates the work in a direction that’s ultimately counter-productive. (We see this more often as Johns moves through his career – accumulating not merely his own dreams and ‘souvenirs’, but the cultural baggage of an international art star, seemingly taking stock of his influences and antecedents, addressing the art historical canon.) No one can salvage a “False Start” the way Johns can, but there’s no way to finesse a false finish.

With the bullseye target, Johns goes one better than ‘squaring’ the circle. Holding it stationary, he adds the array of ‘faces’ – eyes hidden (the implicit blindfold, in a sense; sharing the single ‘eye’ of the target itself), with the optional reveal (Johns varies the hinged panel that opens to the faces, or separate panels for each slot – as he does with a second iteration that breaks down the decoy/identity into discrete body parts including a face that just barely includes the eyes, as well as an ear, both hand and foot, even phallus. It’s a ‘gesture’ deconstructed and rationalized. It’s a signing by the senses – sight, sound, touch; even broaching the notion of a copulation – and what else is shooting a bull’s eye after all? (I don’t think it’s accidental that even more than his flags, the targets were widely publicized and reproduced in the years immediately following their execution and well into the 1960s.) In the meantime, we also see Johns ‘neutralizing’ the expressive brush stroke somewhat more aggressively. The muddling of applications – whether in (mostly primary) colors or grays, blacks and whites becomes bolder, almost explosive, replete with drips that feel comparatively baroque.

With the bullseye target, Johns goes one better than ‘squaring’ the circle. Holding it stationary, he adds the array of ‘faces’ – eyes hidden (the implicit blindfold, in a sense; sharing the single ‘eye’ of the target itself), with the optional reveal (Johns varies the hinged panel that opens to the faces, or separate panels for each slot – as he does with a second iteration that breaks down the decoy/identity into discrete body parts including a face that just barely includes the eyes, as well as an ear, both hand and foot, even phallus. It’s a ‘gesture’ deconstructed and rationalized. It’s a signing by the senses – sight, sound, touch; even broaching the notion of a copulation – and what else is shooting a bull’s eye after all? (I don’t think it’s accidental that even more than his flags, the targets were widely publicized and reproduced in the years immediately following their execution and well into the 1960s.) In the meantime, we also see Johns ‘neutralizing’ the expressive brush stroke somewhat more aggressively. The muddling of applications – whether in (mostly primary) colors or grays, blacks and whites becomes bolder, almost explosive, replete with drips that feel comparatively baroque.

Johns was already deep into his evisceration of linguistic and cultural conventions and value assignments by way of his muddled primaries and secondaries and contradictory stencilings; and, beyond the matter of ‘devices’, presumably focused on tools and extensions (I tend to think of it as Johns’ groundwork for a poetics and rhetoric), when it is said that Rauschenberg presented him with a simple map – the kind handed out to elementary school students, suitable for coloring. I can accept this a few decades after the fact only because it seems increasingly clear that Johns has not been unconscious of addressing his own mythology right alongside the embedded cultural mythologies of his most seminal work. (‘When the fact becomes legend….’ etc.) Still I have to believe Johns would have eventually arrived at this ultimate cultural/political ‘painting over’ at some point after his flags. Could there have been a more arbitrary ‘overlay’ than the political boundaries of the western United States? Johns has at this with some gusto. I’ve always loved the fact that he includes some of the Mexican states and Canadian provinces. (e.g., Chihuahua; Saskatchewan); and the adjacent bodies of water are always at least as important as the landmass. (Or at least that’s what the painting on the canvas tells us: for someone as intent upon neutralizing the expressive brush, Johns has a way of inviting the viewer in for a closer look. It’s not for nothing he returns to Frank O’Hara (effectively sectioning a ‘flag’ into a hinged ‘book’ for “In Memory of My Feelings—Frank O’Hara” – this in 1961, the same year as his first “Map”). There are two in this show, including MoCA’s beautiful greiged-out specimen from 1962 that once belonged to Marcia Weisman. There is also a second O’Hara tribute – this one, a lithograph of the original charcoal “Skin,” with an uncommonly elegiac poem (“Skin with O’Hara poem,” 1965). “Manifest Destiny”? O’Hara captures more than a little of where Johns may be headed (along with the rest of us!).

Johns was already deep into his evisceration of linguistic and cultural conventions and value assignments by way of his muddled primaries and secondaries and contradictory stencilings; and, beyond the matter of ‘devices’, presumably focused on tools and extensions (I tend to think of it as Johns’ groundwork for a poetics and rhetoric), when it is said that Rauschenberg presented him with a simple map – the kind handed out to elementary school students, suitable for coloring. I can accept this a few decades after the fact only because it seems increasingly clear that Johns has not been unconscious of addressing his own mythology right alongside the embedded cultural mythologies of his most seminal work. (‘When the fact becomes legend….’ etc.) Still I have to believe Johns would have eventually arrived at this ultimate cultural/political ‘painting over’ at some point after his flags. Could there have been a more arbitrary ‘overlay’ than the political boundaries of the western United States? Johns has at this with some gusto. I’ve always loved the fact that he includes some of the Mexican states and Canadian provinces. (e.g., Chihuahua; Saskatchewan); and the adjacent bodies of water are always at least as important as the landmass. (Or at least that’s what the painting on the canvas tells us: for someone as intent upon neutralizing the expressive brush, Johns has a way of inviting the viewer in for a closer look. It’s not for nothing he returns to Frank O’Hara (effectively sectioning a ‘flag’ into a hinged ‘book’ for “In Memory of My Feelings—Frank O’Hara” – this in 1961, the same year as his first “Map”). There are two in this show, including MoCA’s beautiful greiged-out specimen from 1962 that once belonged to Marcia Weisman. There is also a second O’Hara tribute – this one, a lithograph of the original charcoal “Skin,” with an uncommonly elegiac poem (“Skin with O’Hara poem,” 1965). “Manifest Destiny”? O’Hara captures more than a little of where Johns may be headed (along with the rest of us!).

: : :

in a season of wit

it is all demolished

or made fragrant

sputnik is only the word for “traveling

companion

here on earth

at 16 you weigh 145 pounds and at 36

the shirts change, endless processions

but they are all neck 14 sleeve 33

and holes appear and are filled

the same holes anonymous filler

no more conversion, no more conversation

the sand inevitably seeks the eye

and it is the same eye

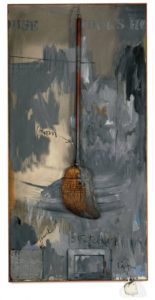

Johns is personal before he is political; but for all his patented reserve, he’s alive to experience outside the studio. He almost certainly craves it. But there’s also some distrust there. (Consider if you will, “Liar,” from 1961 – not the only iteration of this subject (de/vice?) I believe.) The devices come back to the studio – which he’s not afraid to characterize as a “Fool’s House” (1962 – in which the broom seems to do double duty as a kind of pendulum). The studio is where he can set them to work in ‘off-label’ applications, if you will – the off-label operations that plot some part of his consciousness.

Johns has a way of making us feel the passage of time. We alternately swing and suspend ourselves in many of these works. As he is becoming famous during the 1960s, we see evidence of his encounters with other artists (who will soon enjoy their own fame), notably including Warhol. He’s more transparent about his preoccupations and strategies – though he calculatedly avoids attempts at ‘valuation.’ Johns shows them to us not so much as fungible ‘devices’, but – on the same continuum with his targets – as ‘decoys.’ We’re compelled to keep looking, but prompted to quickly move on. There is a period in the late 1960s when he seems to lose his ‘voice’ (a concept he clearly understood, though Samuel Beckett, among other writers, gave him access to a literary voice he seems to have recognized as an analogue of his own), and falls back on his now classic subjects and devices. Johns is awkwardly placed in relation to the Pop movement that has already swept the art world – considered a progenitor, yet unlikely to tap into any of its endless stock of commercial and mass media imagery. If anything, Johns seems to retreat still further from the mass-cultural image, his focus shifting to the interstitial. He might easily have worked in the appropriated interstices of such images; but little of this material comes back to his studio. I can only speculate here, but there are a number of deterrent factors that work against Pop influencing or redirecting his practice. Part of is simply the sense that once returned to the world as a finished artwork, its ‘hidden noise’ (if I can borrow a Duchampian metaphor) will be exposed and its broadcast, mass-reproduced commodified actuality returned to the mass-commercial domain from which it was plucked. Obviously this worked for Warhol, and Lichtenstein to some extent. They’re addressing mythologies, too – but typically mythologies that are already commodified if not culturally metastasized. The other problem is Johns’ avoidance of the figure. In the Johns-ian universe, the figure is either a shadow or a decoy. It’s quite a few years before Johns takes up this problem (not incidentally also addressing issues of transaction and commerce).

Johns has a way of making us feel the passage of time. We alternately swing and suspend ourselves in many of these works. As he is becoming famous during the 1960s, we see evidence of his encounters with other artists (who will soon enjoy their own fame), notably including Warhol. He’s more transparent about his preoccupations and strategies – though he calculatedly avoids attempts at ‘valuation.’ Johns shows them to us not so much as fungible ‘devices’, but – on the same continuum with his targets – as ‘decoys.’ We’re compelled to keep looking, but prompted to quickly move on. There is a period in the late 1960s when he seems to lose his ‘voice’ (a concept he clearly understood, though Samuel Beckett, among other writers, gave him access to a literary voice he seems to have recognized as an analogue of his own), and falls back on his now classic subjects and devices. Johns is awkwardly placed in relation to the Pop movement that has already swept the art world – considered a progenitor, yet unlikely to tap into any of its endless stock of commercial and mass media imagery. If anything, Johns seems to retreat still further from the mass-cultural image, his focus shifting to the interstitial. He might easily have worked in the appropriated interstices of such images; but little of this material comes back to his studio. I can only speculate here, but there are a number of deterrent factors that work against Pop influencing or redirecting his practice. Part of is simply the sense that once returned to the world as a finished artwork, its ‘hidden noise’ (if I can borrow a Duchampian metaphor) will be exposed and its broadcast, mass-reproduced commodified actuality returned to the mass-commercial domain from which it was plucked. Obviously this worked for Warhol, and Lichtenstein to some extent. They’re addressing mythologies, too – but typically mythologies that are already commodified if not culturally metastasized. The other problem is Johns’ avoidance of the figure. In the Johns-ian universe, the figure is either a shadow or a decoy. It’s quite a few years before Johns takes up this problem (not incidentally also addressing issues of transaction and commerce).

It’s around this time that Johns takes up the flagstone wall that will become one of his stock motives in the next decade; and not long thereafter, he came across the cross-hatching device that has figured into so much of his work ever since. It’s hard to say whether he came across the cross-hatching device before or after his encounter with the Edvard Munch self-portrait “Between the Clock and the Bed.” (It’s almost as if Johns uses the motif to address the problem of portraiture, only to dispense with the portrait altogether.) This becomes a dominant motif in Johns’ work over the decades since he first makes reference to it. It lacks the iconicity of his previous work; but then Johns is always looking for a way to subvert the iconic. The cross-hatching becomes infinitely elastic in his hands – variously pitched, rotated, inscribed and faceted, lozenged, crystallized and embroidered; with palettes ranging from primaries to secondaries or still more chromatic; or rendered in black-and-white, grisaille or greige. At their richest and most animated, they seem almost to dance – or at least move. Johns’ homage to Duchamp’s formidably armored ‘Nude’ (or the inaccessible ‘Bride’ – a work Johns has frequently obsessed over)?

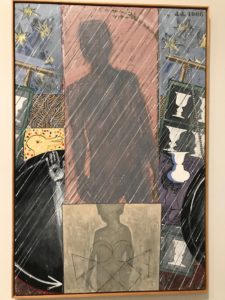

At a certain point (the 1980s), Johns finally returns to the figure. He might well argue that he never left it; and it’s not as if body parts, or references to individuated identity are entirely missing from his work up to this point. But around this time Johns is locating his own zero-ground – really the groundwork of modernism: not just shadowing Duchamp (and he clearly adores Duchamp’s ‘dust’ drawings, his post-Cubist proto-conceptual pseudo-mechanical drawing and painting), but returning to (all but tracing) Cezanne, Picasso, revisiting Barnett Newman, alternately excavating techniques and devices from the art historical canon, and referencing his own as if they were mere footnotes. Cross-hatching elides into the faux-bois of late Cubism (and even trompe l’oeil, which seems faintly ridiculous). A photograph transfer of Leo Castelli is foregrounded (but jigsawed as if pieced from a puzzle), along with a postcard-type print of the Leonardo “Mona Lisa” (and so labeled) – an homage to Duchamp, but also plainly a joke. Some of this work takes on the quality of a puzzle. We have come a long way from the device-subjects of his early works to something inescapably personal.

At a certain point (the 1980s), Johns finally returns to the figure. He might well argue that he never left it; and it’s not as if body parts, or references to individuated identity are entirely missing from his work up to this point. But around this time Johns is locating his own zero-ground – really the groundwork of modernism: not just shadowing Duchamp (and he clearly adores Duchamp’s ‘dust’ drawings, his post-Cubist proto-conceptual pseudo-mechanical drawing and painting), but returning to (all but tracing) Cezanne, Picasso, revisiting Barnett Newman, alternately excavating techniques and devices from the art historical canon, and referencing his own as if they were mere footnotes. Cross-hatching elides into the faux-bois of late Cubism (and even trompe l’oeil, which seems faintly ridiculous). A photograph transfer of Leo Castelli is foregrounded (but jigsawed as if pieced from a puzzle), along with a postcard-type print of the Leonardo “Mona Lisa” (and so labeled) – an homage to Duchamp, but also plainly a joke. Some of this work takes on the quality of a puzzle. We have come a long way from the device-subjects of his early works to something inescapably personal.

Instead of ‘complicating’ the painting, Johns is at this point simply making complicated paintings. He also has to be aware that they don’t ‘scan’ quite as easily as his device-subjects; and moving forward between the 1980s and 1990s, the subjects (which seem to range from deepest sense memory to vague apprehensions of preordained disaster) appear somewhat more organized. In a sense, he has moved from one interstitial mythology to another – not so much his own mythology, but a larger mythology that enfolds and envelops him. Finished appearance to one side, in so much of this work he is not compartmentalizing so much as unpacking; ‘pasting up’ rather than painting over. His souvenirs are devices and vice-versa. In his series “Seasons” (all four of which are assembled in the Broad’s show), he makes explicit his ‘deep dive’ into the past, his ‘full circle’ return to ‘devices’ and landmarks that plotted the course of consciousness. In a later untitled work, a blueprint of a childhood home is overlaid almost as an architectural element. The work is as flat as ever; but it’s as if Johns invokes depth as an overshadowing past which must inevitably return to the surface.

‘Between clock and bed,’ he locates rope and ladder, classic vessels (and the silhouettes traced by their moldings, flags (and Castelli – the man who showed them to the world) and (again from Picasso), reference to a fallen Icarus – a cautionary tale no less timely now than when it was first recorded. The mythologies are multiple here. ‘Values,’ per se, are not neutralized, but rather presented neutrally. If those vessels and silhouettes represent a kind of ‘grail’ for Johns, we understand that it is imposed on no one else. ‘Truth’ is not a singularity in Johns’ domain; neither is he asking for the viewer’s consent. Hence my ambivalence about the reference to ‘truth’ in the show’s title. Certainly Johns aims for a ‘flicker of grace’ in his work; but the thing that ‘resembles truth’ is that unnameable thing that persists and survives the seasons of shadow. Johns presumes only to show us what is important to him. To salvage meaning and grace at a moment when both seem to be under daily assault is achievement enough – and well worth revisiting.

Bravo Ezrha Jean Black!

Wonderful and insightful essay, Ezrha! Loved the carefully examined refeferences**** !!!