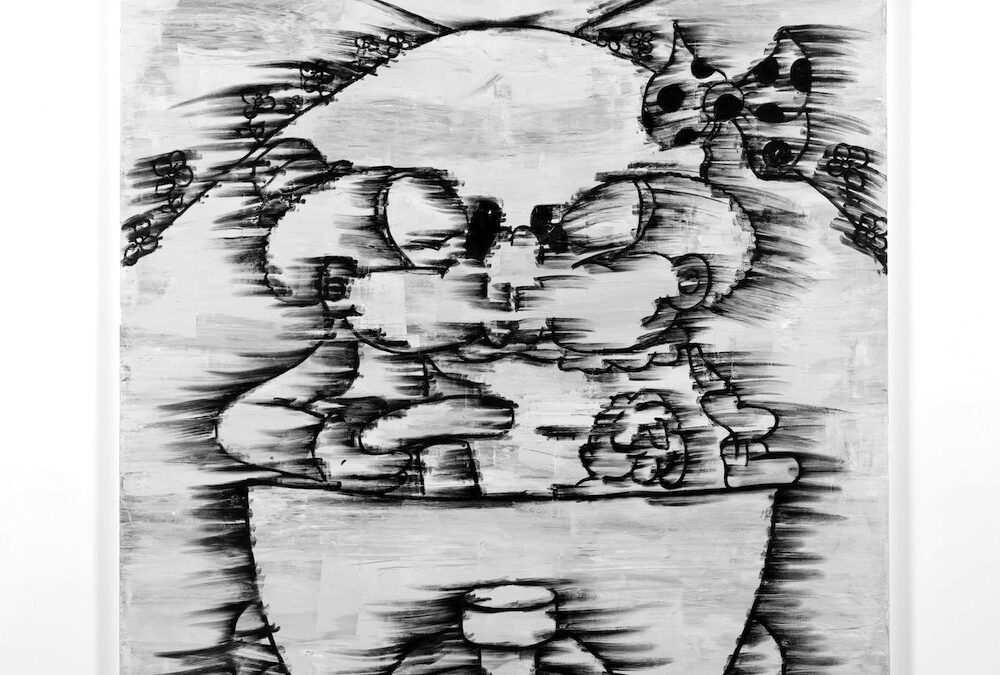

Ah, yes, the front room at Hauser & Wirth: the room you usually walk past on the way to the better shows in the back. There’s a certain type of painting one expects here: Blue Chip filler, the type of young artists who get mentioned in Vanity Fair articles. Where...