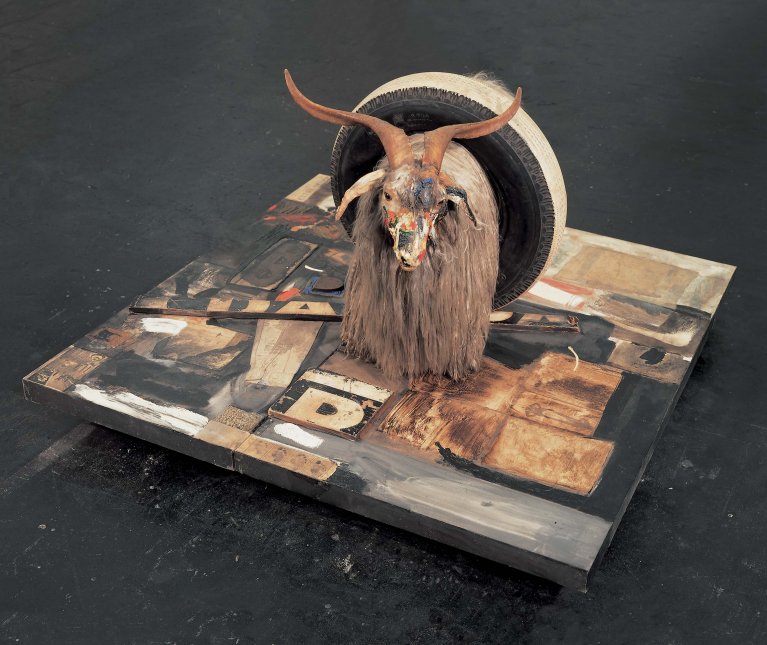

Almost exactly 10 years ago, one of my favorite (and certainly most improbable) curatorial projects was unleashed upon the world: Renee Fox, who was overseeing the development of the Beacon Arts Building in Inglewood (at least its cultural aspect) invited me to do...