DUELLING REVIEWS: MARY CORSE

AND ALL AT ONCE: SUMMER at Various Locations

If you’re reading this, it’s too late. Summer came and went. Pool parties in the Valley? Over. Midnight drives on Mulholland? Gone. We don’t care that you went to Sicily, that your credit score’s crippled because of it, or that you haven’t k-holed at Marcelino’s since...

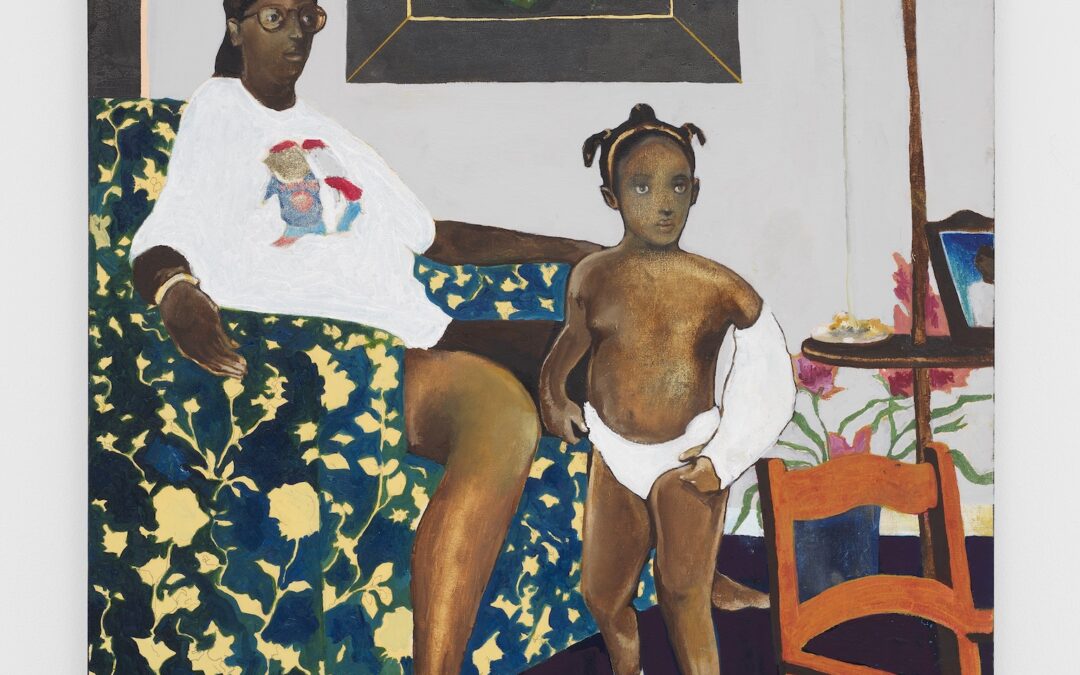

NOAH DAVIS at Hammer Museum

For those familiar with the late painter Noah Davis and the lasting influence of his Underground Museum—the Arlington Heights exhibition space he operated with his wife and collaborator, Karon Davis—the Hammer Museum’s eponymously titled retrospective survey of the...

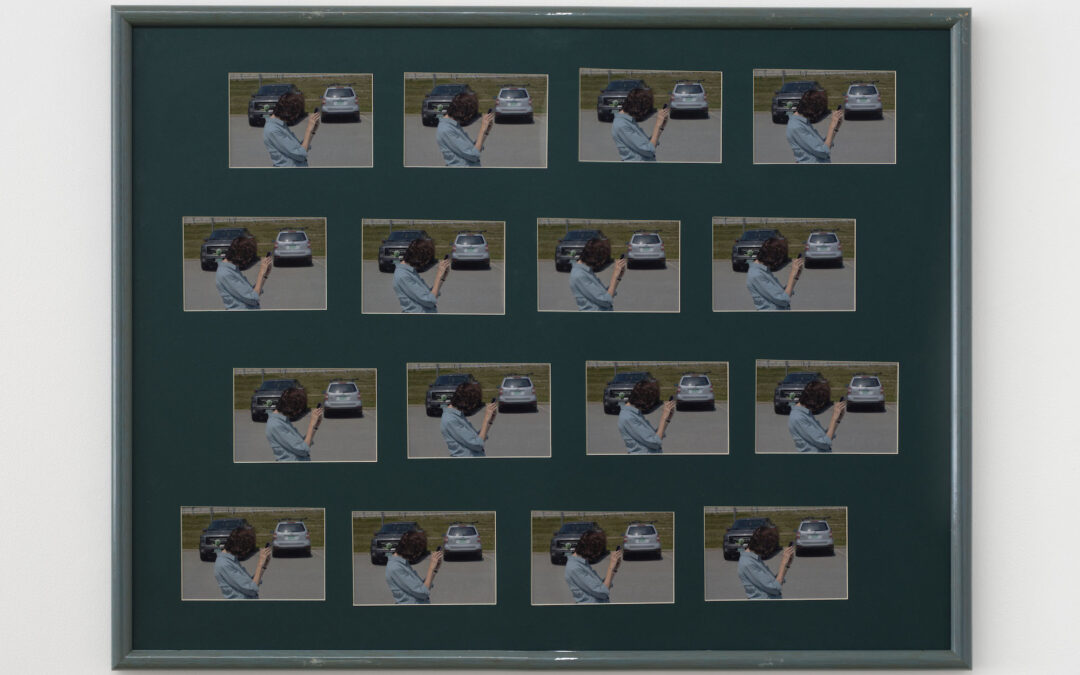

2025 CALIFORNIA BIENNIAL: Desperate, Scared, But Social at Orange County Museum of Art

Navigating the tension between impulsive expression and mastery of one’s craft is a fundamental aspect of the artist’s journey. A similar tension underscores the construction of personal identity that defines adolescence, and hence, the Orange County Museum of Art’s...

HOT! AND READY TO SERVE at American Museum of Ceramic Art

In her 1986 essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Ursula K. Le Guin reimagines human history not as a tale of conquest, but as one of containment. She proposes that the first human tool was not a spear, but a vessel—a bag, a bowl, a bottle. If stories are “carrier...

THE NEW DAVID GEFFEN GALLERIES at LACMA

Once, when I was 12 or 13, I was looking at Fernand Léger’s 1925 painting Composition in the European wing of LACMA’s since-demolished Ahmanson Building when I noticed a small termite crawling across the surface. Slightly alarmed, I notified an elderly gallery...

WILHELM SASNAL at BLUM

The news of BLUM’s abrupt closure after 30 years in Los Angeles reframed the landmark gallery’s final exhibition, Wilhelm Sasnal’s “AAAsphalt,” into an inadvertent elegy for contemporary art in Los Angeles. Entering the massive complex on an early July afternoon, I...

KAORU UEDA at Nonaka-Hill

The night I saw Kaoru Ueda’s self-titled show at Nonaka-Hill, I found myself later at a friend’s house watching YouTube videos of marine life. The viewing experience of the vibrating patterned creatures felt nearly identical to Ueda’s obsessively precise paintings of...

JULIANA HALPERT AND CHRIS KRAUS (With Additional Art by Luis Baez) at Bel Ami

To read a novel is to play detective. The detective novel leverages this symmetry: the reader identifies with Sherlock Holmes’s or Philip Marlowe’s driving curiosity. Our favorite sleuths want to get to the heart of the crime; we want to get to the end of the story....

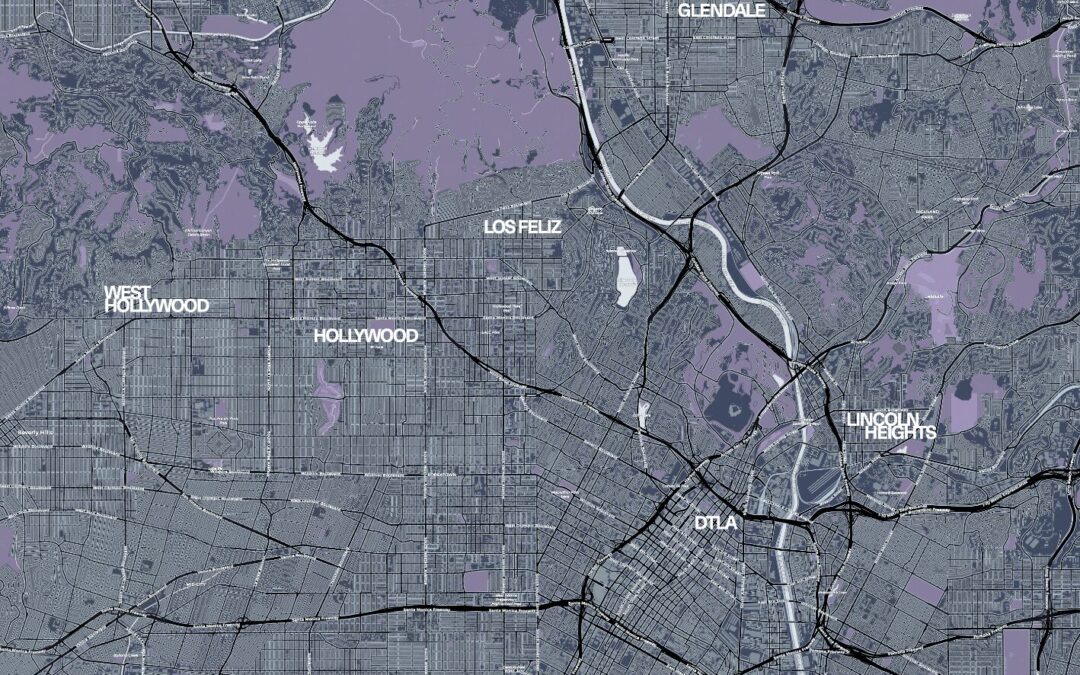

IN SEARCH OF A CITY

Summer is museum season. I’m writing this in early August, a month during which the Angeleno art viewer’s options are fairly clear: Sweat it out on Melrose in pursuit of every lackluster group show; escape to the beach, like the dealers who phoned in those group shows...

STAYING SANE(ish) WITH DR. TRAINWRECK — (print exclusive) Remember the Plan?

Remember I had a plan to discuss overused and oversimplified terms in a way that anyone can understand? In an accessible, user-friendly but without being patronizing manner. Well fuck that. I quote NWA: “Fuck crossing over to them; let them cross over to us.” And to...

AN ARTIST ANSWERS QUESTIONS B. Anele

Tell us who you are. Hi, I go by the name of B. Anele. I am a trans disciplinary artist originally from the South, but somehow, I consistently find myself in other locations. My work as an artist has found me in the midst of being someone who is looked out for while...

COLLECTING THOUGHTS Erin Saluti

Tell us who you are in 50 words or less. I am a multi-hyphenate creative and collector, founder of The Edicurial Collection, and founder and creative director of Eittem, a functional sculpture studio in Manhattan. Trained in art history and interior design, my...

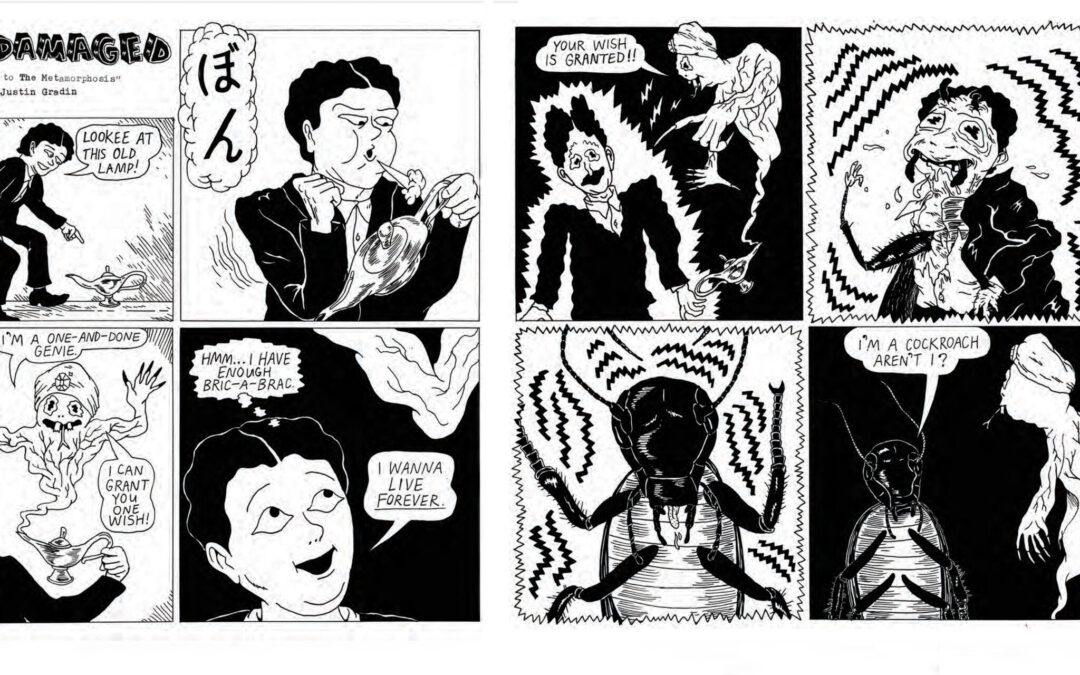

ART DAMAGED Prologue to the Metamorphosis

POEMS

Drink On It Palm Springs is a white blur, scorched into the fabric of time, an escape from the density of sycophants, uggos, and sadsacks. Until now, I had only seen desert flowers on Instaflam, posted by those true believers eager to reveal their sensitivity to...

GALLERY DOGS

LUDOLOGY

Deliver to us, in JPEG form, a pair of artworks—one from before 1900 and one from anytime after—that have an interesting visual connection (that is: one any viewer can plainly see). Most interesting juxtaposition wins! Artillery will choose a winner from the entrants....

STAYING SANE(ish) WITH DR. TRAINWRECK — (print exclusive) Dear Dr. Trainwreck

Dear Dr. Trainwreck, How can I, a layman, tell the difference between someone I have to cut some slack for because of their mental health diagnosis, and someone who is just being a jerk and blaming their diagnosis? Don't some conditions make conversations around this...