Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: Art magazine

-

Dozie Kanu’s “to prop and ignore”

Manual Arts, Los AngelesThe sculptures in Dozie Kanu’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles flirt with functionality but refuse to reveal a clear purpose. Instead, these stylish hybrids possess the elegance of aspirational interior design and the subtle menace of dystopian relics. Many of the works contain familiar elements—a vintage headboard, an ATM machine, rubber plungers—but their relationship to our bodies is permanently transformed. The plunger heads are attached to spiky metal sticks—making them nearly impossible to hold. Meanwhile, the ATM machine stands covered in matte black clay, its buttons buried. These forms speak to recognizable material needs and domestic space, but the logic that binds these combinations remains poetic, not practical.

Sparsely installed in an airy barn-like structure, Kanu’s material choices invite close study. In trial foundation study for victorian revival (all works 2021), a few stalks of charred bamboo stick out from a large array of earthy-red blocks with rounded edges. The smooth bulbous bricks feel chic and futuristic while the bamboo recalls improvised structures built without steel reinforcing. Though uniform appearance, tiny imperfections in the surfaces of the pillow-like bricks indicate that they are sculpted and finished by hand. A rectangle of plywood lies on the floor next to this cluster, its flat face forming distinct wings of this tidy assemblage. After noticing a sliver of reflected light on the floor, I got on my hands and knees to inspect closer. Kanu placed thin steel plates beneath each block like a metallic coaster—a detail that feels integral to the character of the work even though it is nearly illegible. He also carefully notched the bricks to receive the sections of bamboo, neatly holding them in place. The peculiar specificity of these decisions lands like the syllables of a foreign language in which our comprehension is limited. These delightfully strange moments elicit curiosity, wonder, and excitement punctuated by occasional flashes of recognition.

Dozie Kanu, trial foundation study for victorian revival, 2021 trial foundation study for victorian revival resembles modular construction techniques, and a framed floorplan on a nearby wall adds specificity to the architectural allusions in the title. The outline of the structure depicted corresponds to the shape of Kanu’s sculpture and the labels on the rooms in this schematic contain markers of affluence—or at least suburban stability: “family room”, “breakfast nook”, and “two-car garage”. The comfortable proportions of this suburban home contrast with the lean aesthetics of Kanu’s sculpture, which manages to feel both luxurious and like an improvised prototype. The choice to reimagine the foundation of this particular home in a sculptural vocabulary feels personal but without nostalgia. Is this his childhood home? Or a home he coveted? Suburban developments are not known for innovative design, but they document how aspirations coalesce into physical structures. This pairing left me contemplating the seemingly paradoxical accomplishments of visionary architecture: structures that transform the scope of our dreams while responding to practical needs.

Dozie Kanu, Slessor 2.0, 2021 Elsewhere in the show, the artist’s juxtapositions strike a more confrontational note. Slessor 2.0 consists of a face-off between two small head-shaped masses that contain bright lights. Modeled on the type of sparring helmets common in martial arts, these hand-carved pieces of black marble are the size of grapefruits and nearly identical except for the pattern of delicate white veins running through the stone. These tiny helmets sit atop steel pipes that connect to a sinister-looking piece of found metal with two dozen openings in its parallel tubes—a gas burner it turns out. The scene is puzzling. Staring through the openings in the marble to determine the source of the light doesn’t yield any more information about the protagonists of this bizarre duel. A piece of frosted glass hides the bulb, and a fan somewhere inside hums continually (presumably cooling the lightbulbs). The individual components of this piece aren’t all that wild, but collectively they generate an unruly energy. This haunted appliance would certainly illuminate a room, but the intensity of its vibes would not be easy to live with.

Dozie Kanu, At The Moment, 2021 At The Moment is the most overtly political work in the show, and also the funniest. The sculpture is essentially an ATM machine covered in matte black clay with the artist’s fingerprints visible all over its surfaces. The cash machine sits atop what can only be described as a small prison cell—binding blackness to the racist machinery of carceral capitalism. Kanu’s transformation immediately evokes the predatory and exclusionary financial practices that form one of the sturdiest legs of white supremacy in this country. After all, this is the kind of ATM that you would find at a bodega, not the fancy touchscreen kind at the bank. Other aspects of the work are just plain silly. Oval-shaped wings protrude from either side of this tall box, as to propose that this defunct terminal might as well make itself useful and become a table. The dimpled clay coating also has the effect of making this banking device look plump and cartoonish—as if it were a racist but jovial Teletubby.

Kanu’s use of found objects brings a layer of complexity into the work without puncturing the ambiguity that makes his sculptures visually compelling. The success with which he integrates heterogeneous materials comes from the focus and restraint with which these elements are composed. Forging new aesthetic languages often requires cannibalizing the past, but the problems we address rarely change. Kanu’s enigmatic assemblages feel like relics from a future civilization whose hopes and fears mirror our own.

Dozie Kanu: “to prop and ignore”

Manual Arts, Los Angeles

May 6th – September 15th, 2021

Peter Brock is an artist based in Brooklyn, NY.

-

Remarks on Color: Subterranean Smog

September’s HueSubterranean Smog is not one color or another, but a sickening miasma of grays, browns and a lingering smoky orange. Drawn from the bowels of the earth, SS identifies with the antihero — Pig Pen in Charlie Brown, Sir Gawain, the Green Knight, Alex from a Clockwork Orange, Lestat from the Vampire Chronicles. A self-proclaimed anarchist, apocryphal, and constantly distracted, the Great SS wanders the streets of Boise Idaho in search of the meaning of life. Once, for a moment in October of 1975 he thought he discovered it in the recesses of a cherry donut, but alas it was only a sugar rush.

In an attempt to counteract his saturnine nature, and to finally commit to being one solid hue, Subterranean Smog purchases thirteen burnt orange suits with matching socks the color of apricots. For the first time in his dingy life, SS commits to something, and the sheer fact of this gives him hope for the future.

Despite walking down Main Street in the full spectacle of an ever-brightening morning, wearing such garishness as would put Liberace to shame, Subterranean Smog still feels strangely invisible and nondescript. So, he hires a marching band to accompany him to the grocery store, then adorns his body with all manner of orange flowers, and even dips his body in saffron to garner some much-needed attention. But the fact of his inherent and unavoidable bleakness, smoggy and ill-suited to the rarified life, soon catches up with him.

Realizing he cannot change the truth of who he is and the permanent dinginess of his nature, SS decides instead to embrace it completely, marrying his High School sweetheart, Sky, and even going so far as to open a Smog Check Station in the center of an abysmal little town on the outskirts of nowhere.

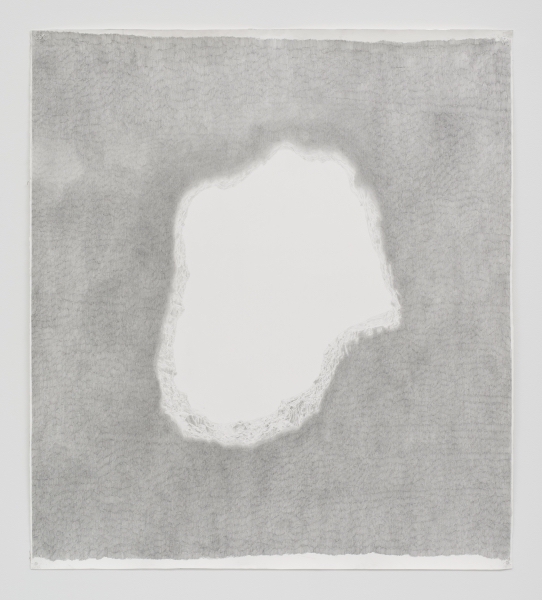

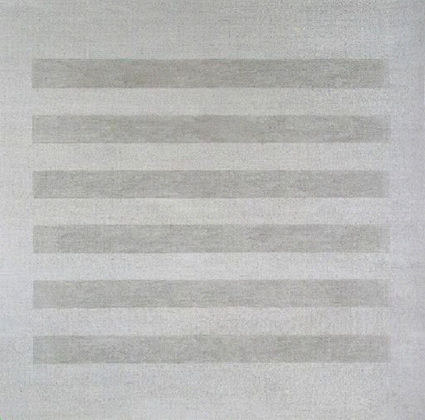

Toba Khedoori, Untitled (hole), 2015 Leslie Hewitt, Sudden Glare of the Sun (installation view), 2012 Larry Pittman, Twelve Fayum From a Late Western Impaerium, 2013 Anish Kapoor, Arqueologia, Biologia, 2016 Albrecht Dürer, Young Hare, 1503 Herald Nix, Untitled Shuswap Lake, B.C. #19 Oct. 12th 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Wilding Cran Gallery Laura Owens, Untitled, 2004 Agnes Martin, Untitled, 1997 Joan Miró, The Birth of the World, 1975 -

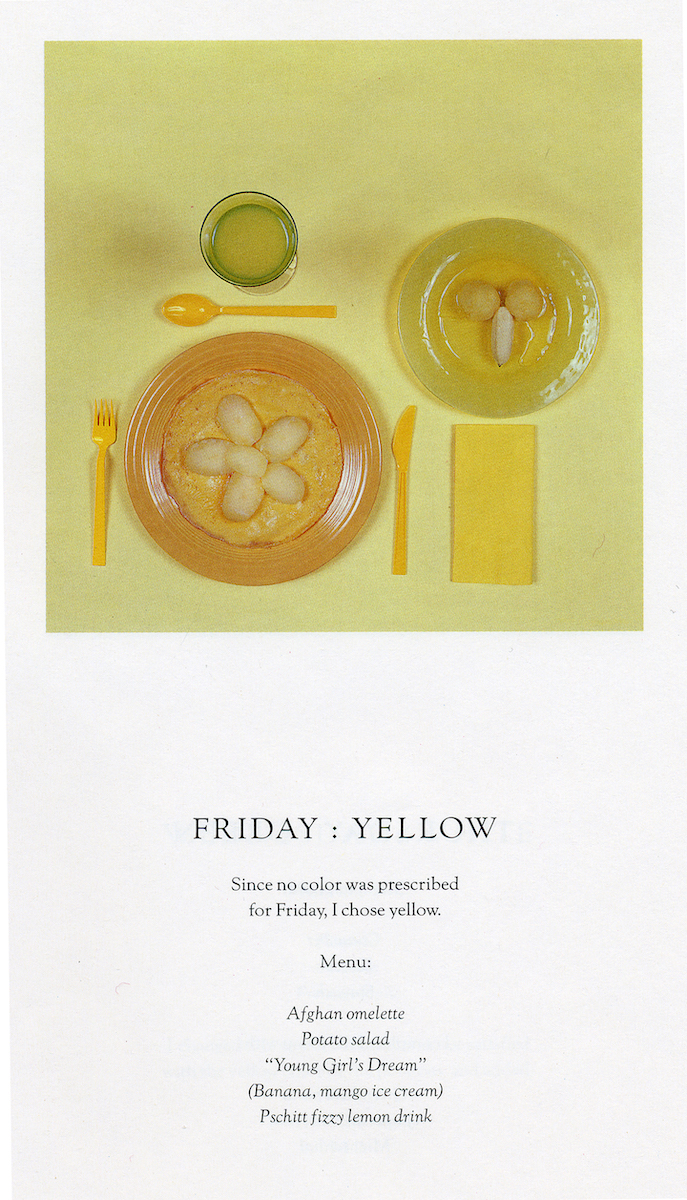

Remarks on Color: Lachrymose Lemon

August’s HueLachrymose Lemon cannot stop weeping. She sobs uncontrollably at everything all the time: the changing of the guards at Buckingham Palace, softball games, dinosaur conventions, the day her favorite chicken finally laid an egg. From the moment the sun rises to the last feeble rays of the day, Lachrymose Lemon greets the world through her tears. She’s what’s called an “indiscriminate crier,” “a perpetual weeper,” “a permanently salty dog,” and these monikers have served her well as for decades her tears have been used to great effect, though she claims manipulation never once entered her mind.

Crocodile tears helped her purchase her first home, a grand affair that sadly overlooked a pig farm in Wisconsin; an Audi convertible with a license plate that reads “cry me a river,” and several whirlwind trips around the world. Lachrymose Lemon discovered that most people are more than happy to lower the price on just about anything in assurance that the sobbing might finally come to an END. In fact, she cries so much that the Guinness Book of World Records once interviewed her for a special edition called The Extreme Body which included a man with hemorrhoids the size of grapefruits.

She hasn’t watched a sad movie in over thirty years and those various YouTube videos of abandoned and abused animals send her over the edge every time. The governor of California once approached Lachrymose about the drought crisis with the idea that her excessive tears might be desalinized, which could possibly save the entire West Coast from immolation. She agreed quite eagerly at first only to cry about it for absolutely no reason later.

On any given day you can find various buckets indiscriminately placed throughout the house in case a sudden deluge overcomes her. Her husband often complains that he has yet again “kicked the bucket” on his way to the bathroom in the middle of the night. The fact their house is a veritable minefield of tears makes it impossible to socialize, and so Lachrymose Lemon bumbles on into her oh so solitary life, sour and forever alone.

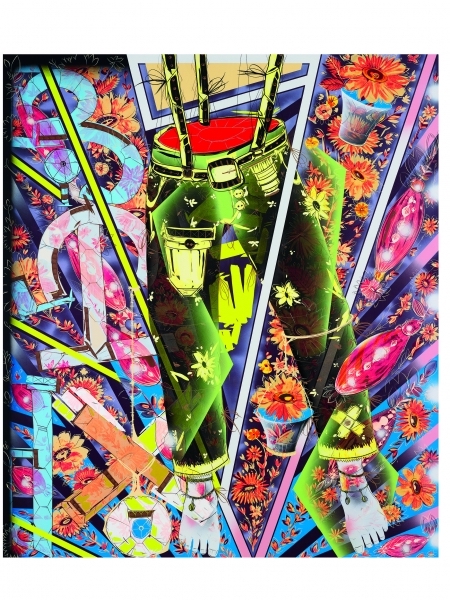

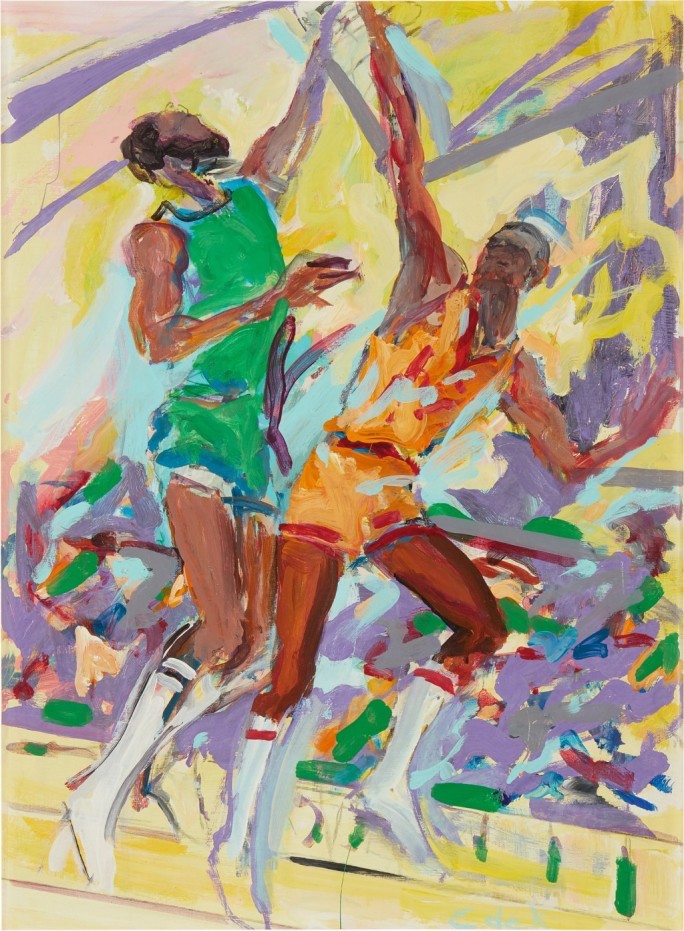

Lari Pittman, Untitled #2, 2009 Alex Hubbard, Mariposa Reina, 2014 Arshile Gorky, The Artist and his Mother, 1936 Sophie Calle, The Chromatic Diet Paul Cézanne, Gardanne, 1885-86 Elaine deKooning, Basketball #1-A William Scott, Bowl Eggs and Lemons, 1950 -

GALLERY ROUNDS: Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Group Exhibition “Above & Below”Fans of Los Angeles’ Craft Contemporary museum will enjoy Above & Below at Shoshana Wayne Gallery. The exhibition features twelve artists working in textile art, ranging from ethnic craft traditions to the wildly unconventional.

The show marks the Los Angeles debuts of Madame Moreau and Yveline Tropéa. Moreau anchors the traditional end of craft in the exhibition with Henry Christoph flag, a beaded ceremonial vodou banner depicting Haiti’s revolutionary war hero and king. Tropéa’s canvases too are covered in beading, illustrating abstracted people and creatures that suggest folklore influences. The French artist lives part-time in Burkina Faso where she has been influenced by Yoruba beading, and where she hires and trains women–disenfranchised kidnapping survivors of Boko Haram–as beaders. Similarly, Gil Yefman felted a bedspread size wall hanging in the show with Kuchinate, a craft collective of African women refugees in Israel.

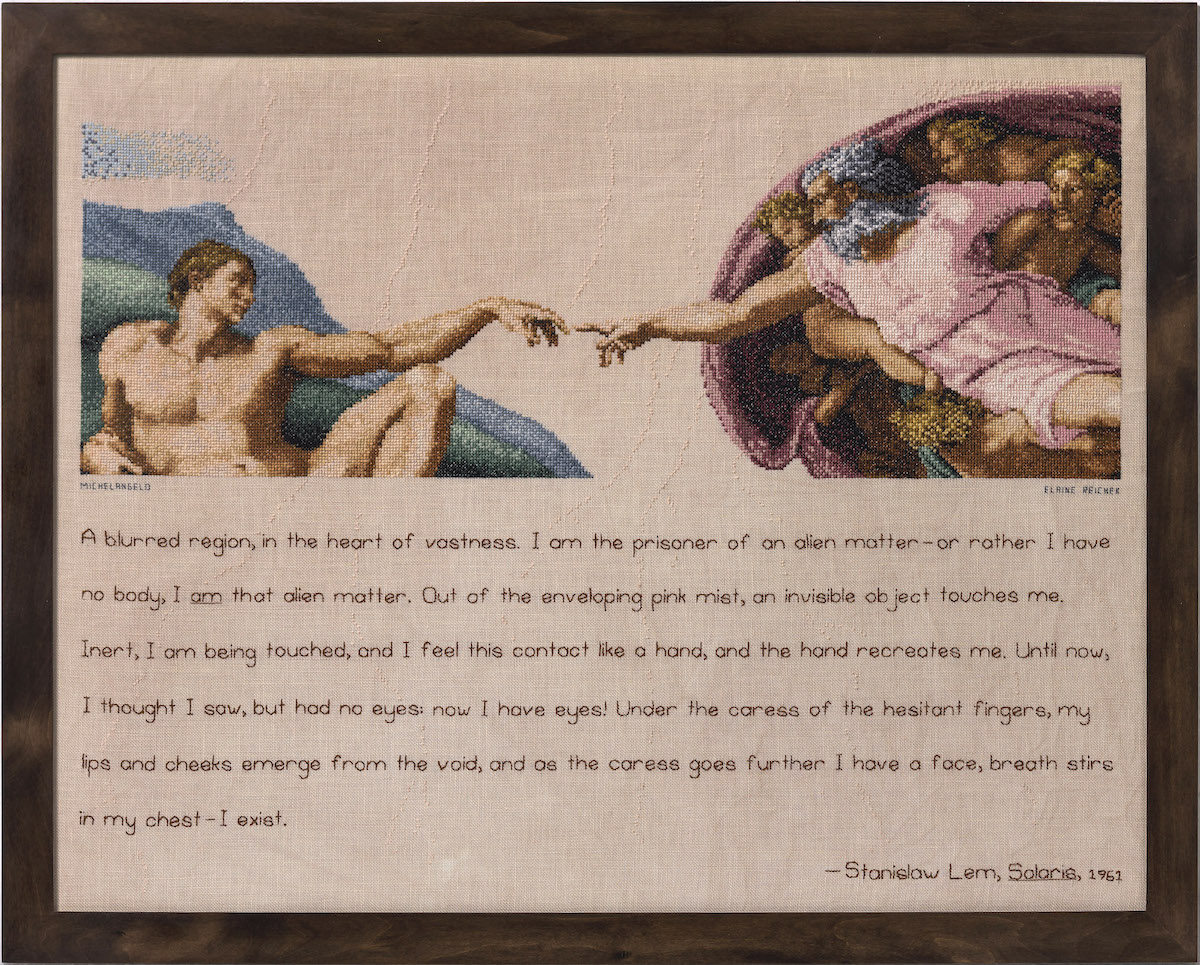

Madame Moreau, Henry Christoph Flag, c. 2020. Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery. Photo by Gene Ogami. Textile art has a long history of dovetailing with feminism, placing value in traditional “women’s work,” as exemplified by Elaine Reichek’s Sampler (A blurred region). Sabrina Gschwandtner likewise draws on this history to pay tribute to early motion picture film editors, largely women whose names are forgotten. Her Hands at Work (For Pat Ferrero) Diptych consists of 16mm film strips sewn into two quilt-like patterns mounted on lightboxes.

The current textile art renaissance is also dovetailing with the LGBTQ movement. Transgender artist Max Colby’s assemblages burst with camp, sprouting phallic shapes covered in beads, plastic flowers and Christmas ornaments. These works find their closest kin in the show in a beaded and studded punching bag, Cloudbuster, by Jeffrey Gibson, a queer Cherokee Choctaw artist. Conical metal beads known as jingles–which adorn the dress of pow-wow dancers–cover the lower half of Cloudbuster, tempting visitors to punch it and make it rain, at least sonically.

Jeffrey Gibson, Cloudbuster, 2013. Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery. Photo by Peter Mauney. As well as beading, weaving is a prominent technique in Above & Below, with interpretations by Terri Friedman, Din Q. Lê, Anina Major, James Richards, and Frances Trombly. Friedman’s wall-sized tapestries particularly push the boundaries of weaving with riotous combinations of colors, textures, negative space, and hidden messages. One aptly says, “Alive.”

Above & Below

June 15-August 28, 2021

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Vera Lutter

Los Angeles County Museum of ArtOne of the most uncanny things about the photographs in Vera Lutter’s exhibition Museum in the Camera, is the fact that many of the galleries depicted, as well as the buildings themselves are no longer there. Lutter shot on site at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) from February 2017 – January 2019, before the recent widespread demolition meant to make way for the new museum structure.

Using both stationary room-sized and portable smaller-scaled pinhole cameras, Lutter created images of both interior and exterior spaces at LACMA, as well as individual works of art. A pinhole camera is a camera without a lens. Light passes through a small hole that functions as an aperture projecting the object or scene in front of the “hole” onto the opposite wall, photographic paper or film. Pinhole cameras usually require long exposure times that results in motion blur as well as the absence of any objects that move continuously in front of the lens. The image created is also a backwards and upside down negative.

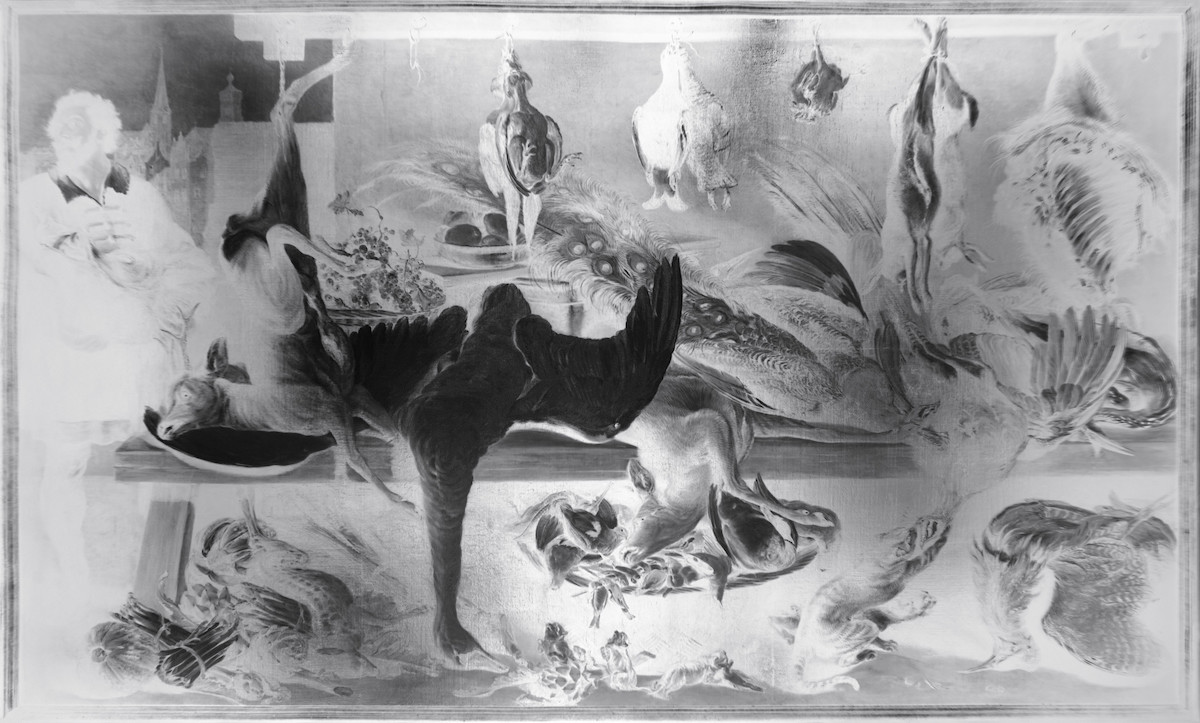

Vera Lutter, Art of the Pacific, II: September 21, 2017–January 5, 2018, 2017–18, unique gelatin silver prints, commissioned by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art through an artist residency supported by Sotheby’s, © Vera Lutter, digital image courtesy of the artist Before gravitating to pinhole cameras in the early 1990s, Lutter turned her New York loft into a camera obscura to project large inverted images onto mural sized sheets of photographic paper to create unique large-scale negatives. She later constructed room-sized cameras she could use on location. Working with a crew at LACMA over two years, Lutter was able to fabricate not just one, but four room-sized cameras that she used to capture aspects of the museum, documenting exhibitions, gardens and the various buildings on LACMA’s campus. She also built smaller pinhole cameras to make individual photographs of specific objects of art and paintings. To create the oversized three panel image European Old Masters: December 7, 2018 – January 9, 2019 (2018-19) Lutter hid the camera behind a specially constructed wall and positioned the vantage point, the gallery lights and even the paintings to perfectly recede in space. The resulting photograph is an eerie and ghost-like image of the gallery in which these old master paintings hung. As a black and white negative, the walls are dark and the is ceiling white with black spots where the lights were positioned. The frames surrounding the artworks glow against the dark walls and in relation to the now lightly rendered paintings. The reflective corridor is devoid of people due to the month long exposure.

Vera Lutter, Art of the Pacific, II: September 21, 2017–January 5, 2018, 2017–18, unique gelatin silver prints, commissioned by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art through an artist residency supported by Sotheby’s, © Vera Lutter, digital image courtesy of the artist Art of the Pacific, II: September 21, 2017 – January 5, 2018 (2017-18) is another three panel photograph (97 1/8 x 168 inches) where Lutter positioned objects and artifacts for the camera. Using objects from LACMA’s Pacific Islands collection, Lutter composed the photograph based on aesthetics, rather than factual relationships stating, “I was allowed to pick all my favorite pieces…. I brought all these characters together that aren’t from the same tribe, and aren’t from the same island, and might not really speak the same language, but I wanted them all to talk to one another.” In the resulting photograph, the three-dimensional objects appear flat, their tonalities a surreal group of tones due to the fact that the image is a negative. The arrangement of objects were similarly finessed by Lutter from inside the camera to maximize the compositional balance within the image.

Installation photograph, Vera Lutter: Museum in the Camera, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2020, art © Vera Lutter, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA Included in the exhibition are pinhole photographs of individual artworks carefully shot on custom made “copy-cameras.” There are pinhole cameras arranged to face easels onto which Lutter placed specific paintings. Though recognizable as paintings, Lutter’s photographs highlight different aspects of the originals as again they are presented as reversed black and white negative images.

When Lutter first visited LACMA to contemplate the project, she became enamored by the area known as Rodin’s Garden. Not only was it beautiful, but it represented Los Angeles, with its billowing palm trees and traffic just beyond the fence. The plaza was both quasi-urban and a cultural landmark simultaneously. Her image, Rodin Garden, I: February 22, 2017, (2017) exemplifies this experience. Though recognizable, the quality of light and blurriness of the treetops takes one beyond reality into a dream-like environment. It is curious that Lutter includes two versions of this image, one is high contrast, while the other is much darker (over-exposed) with a more muted range of tones.

Installation photograph, Vera Lutter: Museum in the Camera, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2020, art © Vera Lutter, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA Lutter’s images call certain photographic truths into question. While they were made with a camera, what was placed in front of the aperture (pinhole) changed due to the long exposures (some took several months). These images are single shots that were created not in fractions of a second, but over time and this durational aspect gives the finished photographs an uncanny quality. Although “real” they appear surreal because LACMA no longer has many of the courtyards or galleries Lutter documented and most of the art is in storage. Wandering through her exhibition, one cannot help but reflect on the demolished architecture and memories of the museum. While the works on view in Museum in the Camera serve as a reminder of what LACMA was, more importantly they are intriguing images and new works of art that re-present what is gone in surprising and unusual ways.

Vera Lutter

Museum in the Camera

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

April 1 – September 12, 2021

-

John Knuth’s The Dawn

John Knuth and Writer Matt Stromberg talk Horseshoe Crabs, Manet, Realism and Kids in a Vaccinated WorldJohn Knuth is a Los Angeles-based artist who recently had a solo show with Hollis Taggart Gallery in Southport, CT. His work explores how humanity and material and the natural world intersect and influence each other. “The Dawn” ran from May 15–July 3.

MATT STROMBERG: From its title, the show has an unmistakably optimistic tone. what makes you hopeful? is it for a return to pre-pandemic life, or the possibility of a new way of living?

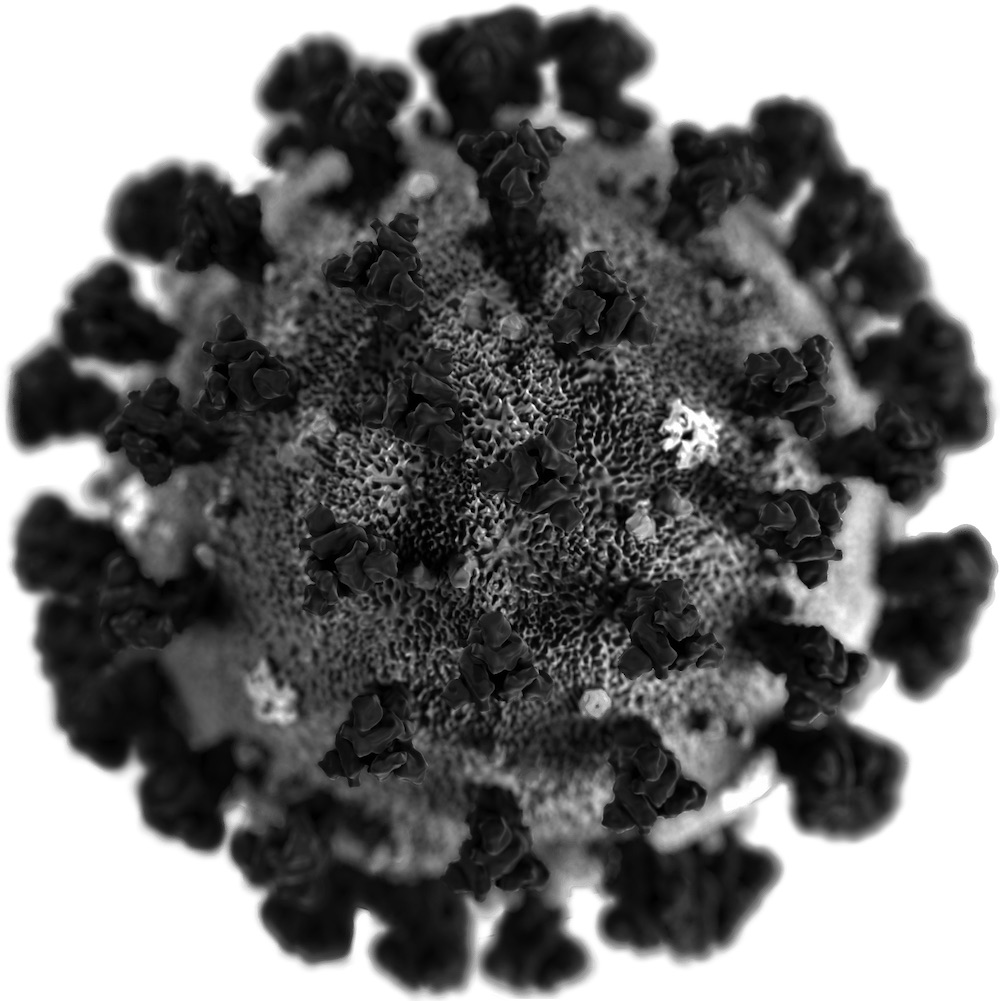

JOHN KNUTH: Yep! The show is conceived around the idea of rebirth. We have been in pupation quarantine for the past year. The vaccines are rolling out and we are emerging like brood X cicadas! I feel it. I think we all feel it.

I caught covid in August and it hit me harder than I think I realized at the time. I had lingering brain fog for about six months. Something changed in me after the vaccine and I have a renewed engagement, inspiration and outlook.

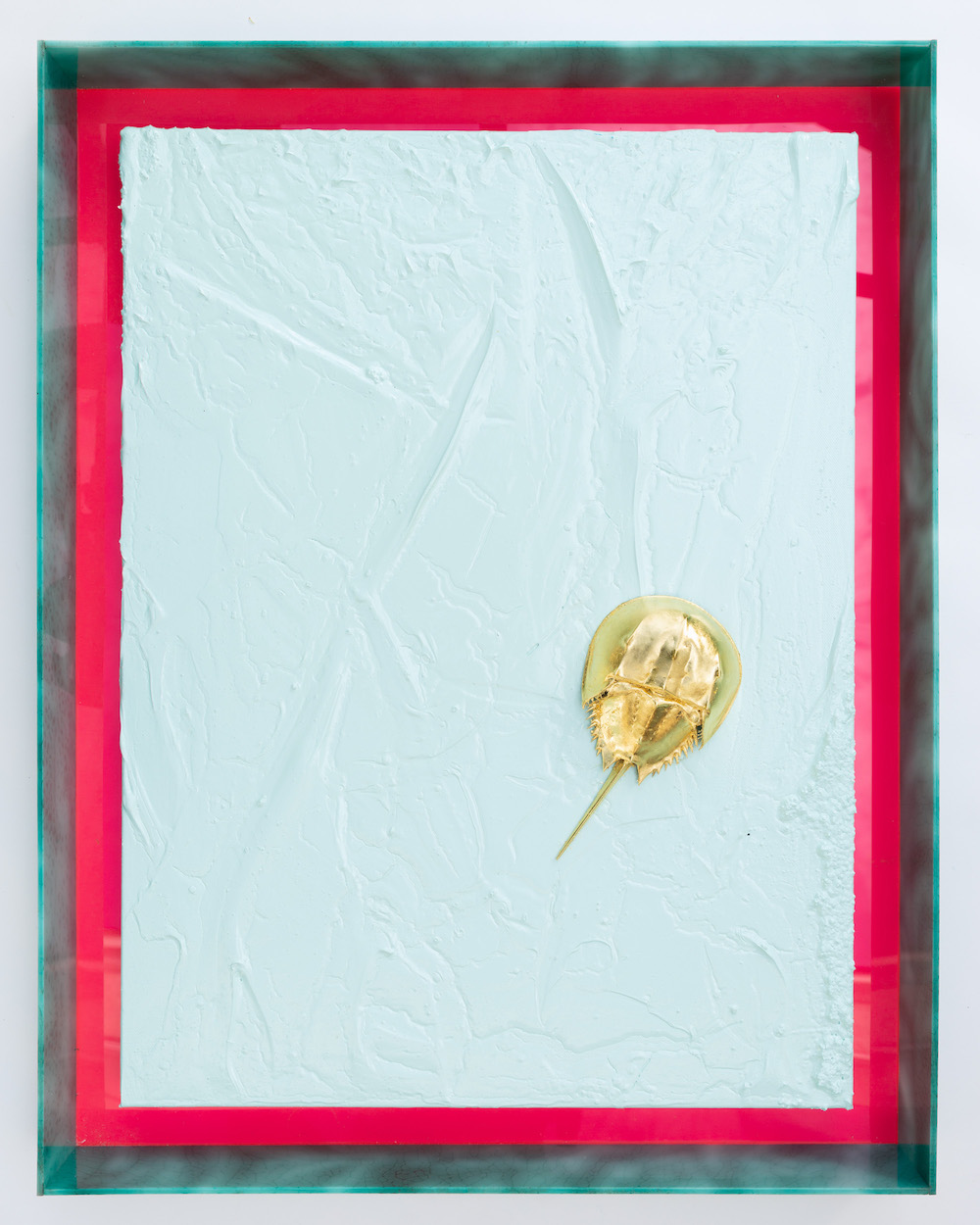

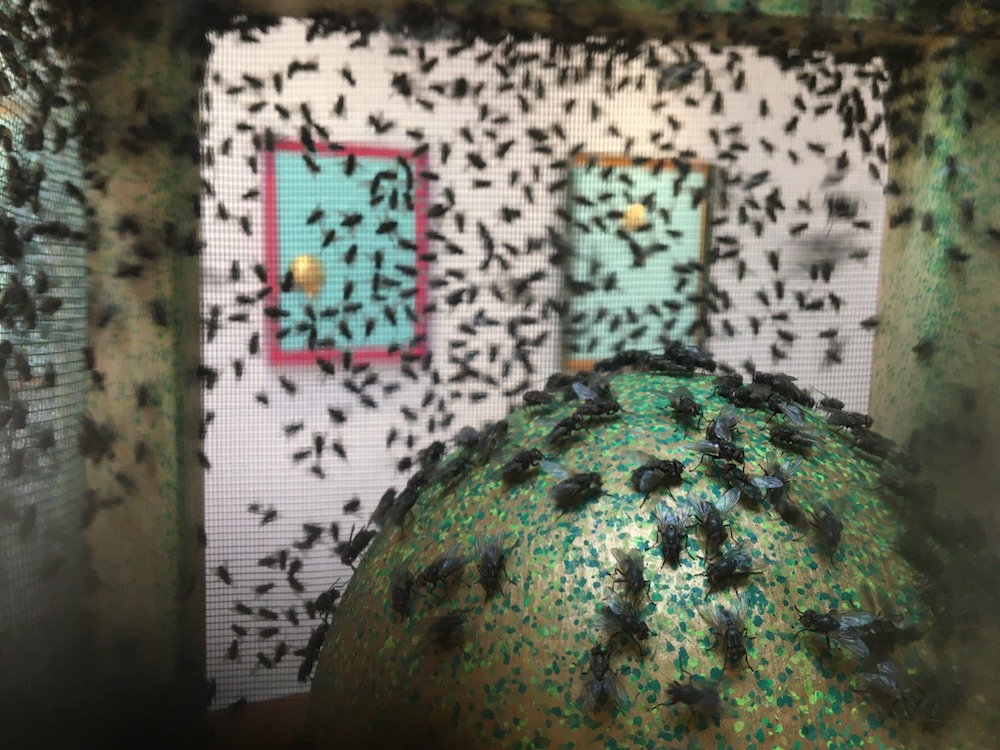

“The Dawn” became the theme for the show. All the colors and compositions for the fly paintings were made with the sunrise in mind: Yellow, oranges, reds, blues and metallics. I added ostrich eggs as a symbol of rebirth and an acknowledgement of the spring. I also added gilded horseshoe crab paintings and turned them into icon paintings celebrating the importance they play in our vaccines.

Installation view “The Dawn.” Photo credit: Ian Byers-Gamber There’s an element of sacrifice in your work, whether in the form of the flies who live their whole lives just to make your paintings, or the horseshoe crabs who give their blood to make vaccines. Is that reflective of the kind of religious upbringing you had in Minnesota?

There are certainly religious themes that are in this show. I gilded horseshoe crab shells with 22 karat gold leaf to turn them into byzantine icon paintings. Horseshoe crabs are instrumental in our vaccine production and most intravenous drugs. Each spring on the east coast, thousands of horseshoe crabs are harvested and milked for their bright blue blood to be used in testing in pharmaceuticals and specifically vaccines. That’s because these animals’ milky-blue blood provides the only known natural source of limulus amebocyte lysate, a substance that detects a contaminant called endotoxin. If even tiny amounts of endotoxin—a type of bacterial toxin—make their way into vaccines, injectable drugs, or other sterile pharmaceuticals such as artificial knees and hips, the results can be deadly. Without putting it too lightly their blood gives us life. I also thought of these paintings as my Warhol Marylin Monroes. Or refocusing the idea of the religious icon painting—Of course the idea of the egg is a symbol for Easter and rebirth.

I’d say the influences of my childhood are certainly throughlines in this show. I grew up on a creek catching snakes and turtles and going to church with my family. I also grew up reading Warhol books. So it is all a part of the thinking in this work.

John Knuth, Horseshoe 1. Photo credit: Ian Byers-Gamber Where do you get the horseshoe crabs from?

I originally wanted to paint with horseshoe crab blood, but no one would sell it to me. It costs $16,000 a pint! I was trying to buy even just an ounce but the companies that harvest and sell it to pharmaceutical companies would not sell it to me. (I should note that no horseshoe crabs were harmed in the production of this show. They have exoskeletons and they shed their shells, so people collect them and sell them online.) You can purchase anything online. In the past year I have purchased rattlesnake venom, a million maggots, ostrich eggs, horseshoe crab shells etc… How do you see artists responding to the Covid-19 pandemic? You see much more art than I do. I don’t know if I have really seen any art that is directly about it yet.

It’s a good question. lots of artists’ recent work has been shaped by the pandemic. You’ve all been alone in your studios, with nothing but your thoughts to keep you company. No students (in person at least), no collectors to schmooze, no fellow artists to connect with. Even if the art is not directly about the pandemic, its about loneliness, alienation, apocalypse. Or engaging with the idea of a reset, that we just go back to “normal” after the pandemic, but we need to actually think about what’s important, how we want to act and live after this cloud lifts. The dawn right? The new dawn, rebirth, the egg. its not about status quo, it’s about a new world.

Installation view “The Dawn.” Photo credit: Ian Byers-Gamber You go and see exhibitions multiple times a week. How has the pandemic and now the vaccine roll out changed your feelings of seeing shows?

To be honest, i never felt unsafe at galleries, even during the middle of the pandemic. Like they were never really that many people at a gallery in the before times. I felt much more anxious at Costco, with scores of people pressing up on you, chin-masking it. Now I feel downright gleeful to be in a gallery. There’s been a funny thing over the past month or so where I’ll go to a gallery, generally a smaller storefront gallery, with my mask on and the gallerist and I lock eyes, and we both take our masks off, since we’ve both been vaxxinated. Its a small intimacy, a show of confidence, of trust. which is quite rare in the art world.

Are you looking at art differently in a vaccinated world?

Taking a break from gallery-going has only made me appreciate seeing art in person so much more. It is a social and physical activity. I rely on instagram and social media to keep me updated, discover new work, share what I like, but it’s not a replacement. Art is a physical thing (unless of course when it’s not), but there’s a smell, a dance you do around objects, even paintings, that doesn’t translate to the screen. Thankfully we had a way to keep us connected and inspired throughout the past year, but as long as artists are picking up a brush, or a lump of clay, or even setting up a fly pen to make work, then we need to see it in person, there’s no alternative.

Installation view “The Dawn.” Photo credit: Ian Byers-Gamber Agreed, it is wonderful to be back in front of the physical objects. I guess my question is more of an emotional or if how you are thinking about art has changed? For instance, I went to the Norton Simon the week it opened back up. It’s a place my wife and I love to visit and it’s our stop to see some masterpieces and have happy hour in the garden. We took our one-and-a-half year old son to see his first art museum. I could tell he was connecting with the paintings. We look at a lot of art books at home together. But when we were in front of Eduard Manet’s Ragpicker, Mateo seemed to connect to the painting. It was quite an emotional experience for me. I think with the incredible homelessness issue in LA and missing a connection to humanity the painting changed for me. I was so touched that Mateo was reaching out and emoting towards the painting. I didn’t expect to be so deeply touched by the experience. Mateo’s reaction and my empathetic experience of that painting in that moment will be a treasured memory.

Mateo at Norton Smith. Photo credit: John Knuth That’s a sweet story about your son, what do you think it was about the Manet that he connected with? Usually when our kids are drawn to figurative work, it’s because the subject looks like someone they know, they can relate it to their own lives. When we’ve taken our kids to the museum, I see them connect more with the physical experience of being there than with the images per se. Like seeing Burden’s Metropolis 2 at LACMA—which is obviously a kid favorite because it’s just a giant race track with dozens of toy cars and trains—it still couldn’t compare to the actual construction going on outside on Wilshire Boulevard) or Nikita Gale’s Private Dancer at CAAM, which is basically a theatrical lighting truss on the ground, with lights flashing and spinning, programmed to coincide with a silent version of Tina Turner’s “Private Dancer.” They couldn’t get enough, running all around it, chasing the lights. What it really drove home for me was the embodied experience of viewing art; these are social spaces where we encounter objects, not just images.

Stromberg’s kid in front of Metropolis II, Photo by Matt Stromberg Which circles back to your work I think, because it’s not just about image creating, but these are objects you’re creating, even the fly paintings have a complex, built-up surface (and a smell!) that doesn’t quite carry through on the screen. And then your decision to incorporate actual horseshoe crabs instead of representations, and the neon plexi which can never quite translate in a photo.

Another stray thought is that as much hope is embodied in your new work, the horseshoe crab as a symbol of science’s mastery over illness, they’re also a bit of a momento mori. The horsehoe crab has been around for hundreds of millions of years and will likely be around after we’ve made ourselves extinct. Some future alien race will find your gold painted horseshoes in their plastic frames (which will most likely not degrade for hundreds of years), and perhaps think it was a portrait of a notable crab painted by a crab artist, with humans never entering their reconstructed narrative. It’s similar to the Ragpicker in a way, the lowliest of the low, whom we walk by and ignore. But the canvas that Manet is painting on will presumably one day just be another pile of rags for another ragpicker to collect and sell to eek by.

I think much of this conversation goes back to Manet or Courbet and Realism who Manet certainly comes out of that lineage. Maybe not as a painting style but as way of approaching art or thinking or making. I think of myself as a realist artist meaning I try to engage with the world, and make artwork that is involved in the world not romantic, not escapist, not nostalgic, not art about art. I make art of and about the world. It is important that the horseshoe crab is real and that the gold leaf is real and not gold paint. It is not a representation it is the real thing. In our vaccinated world this impulse to participate and experience is even stronger.John Knuth was born in 1978 in Minneapolis, Minnesota and lives and works in Los Angeles, California. He received an MFA from University of Southern California and a BFA from the University of Minnesota. Knuth’s recent solo exhibitions Powerplant at Brand New Gallery, Milan, Italy; Base Alchemy at 5 Car Garage, Santa Monica, CA; Master Plan at Andrew Rafacz Gallery, Chicago, IL; Elevated Uncertainty at Marie Kirkegaard, Copenhagen, Denmark; and Fading Horizon at Human Resources, Los Angeles, CA. His works has recently been included in group shows at International Print Center, New York, NY; Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY; MassArt, Boston, MA; Self-Titled, Tilburg, NL; Los Angeles County Museum of Art in Los Angeles, CA; and the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Matt Stromberg is a freelance arts writer based in Los Angeles. He contributes to a range of publications including the Los Angeles Times, Hyperallergic, Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles, The Guardian, The Art Newspaper, KCET Artbound, Terremoto, Artsy, frieze, and Daily Serving.

Editor’s note: This dialogue took place early July, before the resurgence of COVID19 (again).

-

OUTSIDE LA: Un/Common Proximity

Group Exhibition at James Cohan, NYDuring the last year, proximity became a defining characteristic of our daily lives. Geographic proximity limited our access to family, friends and resources, and ideological proximity determined the news we consumed, the information we shared and the concepts we viewed as true or false. This proximity was disruptive, unprecedented and marked a dramatic shift, the repercussions of which are still evolving. This shift is at the heart of the current show at James Cohan. Presenting the work of the 2020-2021 NXTHVN artist fellows, “Un/Common Proximity” reflects the resilience and growth from the last year, as well as the ongoing need for change.

NXTHVN’s annual fellowship is awarded to seven artists and two curators. As was common during the pandemic, the fellows—Allana Clarke, Alisa Sikelianos-Carter, Daniel T. Gaitor-Lomack, Esteban Ramón Pérez, Jeffrey Meris, Ilana Savdie, and Vincent Valdez—had to adjust to new protocols and formed their own quarantine pod, working and growing together as the world around them changed.

Allana Clarke, Relentless, 2021, cocoa butter and beeswax. Courtesy James Cohan. A clear marker of growth, Meris’ sculpture titled Catch A Stick of Fire (2021) hangs from the ceiling with tendrils bursting like a chandelier. At the end of the arms are spider leaf plants, regenerated by hanging grow lights. Next to Meris’ piece is Relentless (2021) by Clarke that addresses the theme of resilience with the word “relentless” written in three-dimensional cocoa butter and beeswax installed directly onto the wall. The use of cocoa butter alludes to healing and self-preservation and relates to Clarke’s exploration of anti-Black sentiment in Western standards of beauty and the methods and materials used to adhere to them. The work is a testament to the ongoing experience of being Black in a society dominated by white norms.

Clarke’s sculpture points to a major dichotomy underlying the works in the show. While we’ve overcome many hardships during the pandemic, inequality and racism remain. Bringing this issue to the forefront, Valdez’s Just A Dream (In America) (2021) is a monumental painting of an exhausted boxer sitting in the corner of a ring in front of patriotic banners and two men, coaches or sponsors, dressed to indicate their wealth. The juxtaposition of the boxer, identified in an essay by curator Claire Kim as Chicano, with the presumably white figures in the background highlights the racial and economic inequalities in America. The painting, installed on two concrete blocks and leaning against the wall, is accompanied by an audio piece by Justin Boyd featuring Jimmy Clanton’s song Just a Dream (1968) that mourns lost love. The song plays softly like a quiet, sorrowful elegy to false hopes of the American dream.

Installation view of Un/Common Proximity with Jeffrey Meris (left) and Vincent Valdez (right). Courtesy James Cohan. As Kim notes in her essay, Valdez’s message is both “resolute and heartbreaking,” two words that can be applied throughout the show. Indeed, resolve and heartbreak have been constant companions to all of us over the last year. What is clear from the show is that although proximity very literally brings us closer together, it also uncovers the ways in which we are deeply divided.

Group exhibition: NXTHVN Studio Fellowship artists

James Cohan, New York

June 12 – August 13, 2021

All photos by Phoebe d’Heurle.

-

Shoptalk

Return of Art Fairs, Painting is “In,” and What The New Normal Looks LikeThe New Normal

We thought the world would end in fire, or possibly in ice. And now we know it can end with a virus. As a child growing up in Taiwan and then later in the US during the Cold War, I often imagined—and literally dreamed—how the world would end. Earthquakes and nuclear holocaust were my usual Apocalyptic scenarios. I did occasionally imagine a strange, contagious disease, but not one quite like COVID-19 where the entire world would be held hostage, so widespread and for so long.

Now as we slip back into public life, we realize that we have changed, and so has the world we return to. Many people will continue to work from home, in full or in part. Students have gotten trained in online classrooms. As someone who’s been teaching on Zoom, it’s clear that online education can’t match the real-life one, though it can certainly supplement it. Museums and galleries have run virtual exhibitions and presentations, and are now reopening at limited capacity. By the time this is published, they could be at increased or full capacity. However, in the past year programming has undergone a radical shift—with more, deserved attention paid to POC and women artists. The world we return to is not the world we left last March. How could it be? Which changes are to be enduring and systemic remains to be seen.

“Shattered Glass” show at Deitch Projects Painting

Painting is coming back, and in a big way, but the painters being featured are not the ones highlighted in the past. There was the extraordinarily exciting “Shattered Glass” show at Deitch Projects, curated by Melahn Frierson and AJ Girard, with 40 POC artists, many of them young and emerging and based in California. I went on the closing day, and there were a couple hundred people there—the largest event I’d attended in a while. And what an energy, what a charge as the artists mixed happily with family and friends, old and new, mostly masked but not able to keep distances. Girard was giving tours, there was a fashion show, and lots and lots of photos were sent to Instagram.

There was also some excellent painting. La Piedra Negra by Vincent Valdez, was one that stopped you in your tracks: a very large painting of the head of a woman, resting sideways on a rock as if listening to something. Her background is a city on fire or perhaps an especially flaming sunset—hauntingly beautiful and not a little unsettling. There were paintings by the Finley brothers: Kohshin Finley’s monochromatically toned Marque and Tiffany shows a young couple in a quiet moment of tenderness, while Delfin Finley’s Rumination portrays the back of a young man with loops of colored ropes slung over his shoulders—a real tour de force of photorealist painting.

The two-woman show at L.A. Louver with Rebecca Campbell and Heather Gwen Martin was a good pairing, featuring two painters with dramatically divergent aesthetics. I thoroughly enjoyed the first show for Brooklyn-based abstract painter Patricia Treib at Overduin & Co.; her lyrical shapes are part Matisse cut-out and pure whimsy.

Sister Corita Kent’s studio in Hollywood Comings and Goings

Galleries continue playing musical chairs. Luna Anaïs has moved from a downtown space to Tinflats in Frogtown—and launched with an opening party drawing a lively, multi-generational crowd for a show featuring Gloria Gem Sánchez and Tidawhitney Lek. Owner Anna Bagirov (full disclosure: Bagirov also helps Artillery with its marketing) is very happy with the bigger space, though it’s leased on a temporary basis, so who knows how long they will be there.

Von Lintel has made another move. They were in Culver City for years, then moved to DTLA, and on May 15 reopened in Bergamot Station with a show by Christiane Feser. “Sadly downtown has suffered immensely from the pandemic,” said Von Lintel via email. “Closed store fronts and countless homeless seem to dominate the scene. I decided that easy access and parking were important for this next post-COVID phase, all of which Bergamot Station in Santa Monica offers.”

Earlier that month, on May 1, I visited Bergamot for a group show opening at Craig Krull, and it was heartening to see how many people showed up. The reception was out in the parking lot, and it was like homecoming week, with lots of longtime-no-see greetings, and people announcing, “I’m fully vaxxed, too.” Even so, we mostly kept our masks on when not drinking.

In recent years Bergamot has been gutted by departures and the uncertainly of development. I recall that at one time there were two competing projects, one that included a hotel and other retail, but right now nothing seems to be underway. There are quite a few empty spaces, and it would be great if more galleries could find their way there.

Hauser & Wirth is adding yet another gallery to its well-feathered cap, with a second LA location. Their current spot in a former flour factory in DTLA is already an art destination, and now they’ve leased a new space at 8980 Santa Monica Blvd. in West Hollywood, scheduled to open fall 2022. The 10,800-square-foot space will be designed by Annabelle Selldorf of Selldorf Architects, designer of their DTLA location. And yes, there will be a restaurant.

Something that is not coming or going, but staying, is Sister Corita Kent’s studio in Hollywood, which she used for making her activist art and teaching from 1960 through ’68. It’s now in private hands, and the owners were planning to tear it down for a parking lot. (Hmm, remind you of a certain Joni Mitchell song?) On June 2, the LA City Council voted unanimously to approve the studio as a Historic-Cultural Monument, thus saving it from demolition. Eventually, the Corita Art Center, which started the petition to save the building, hopes that it can be made into a cultural center. It is plain, even drab, in appearance, but it is historical, and a very small percentage of sites related to women or POC have achieved Historic-Cultural Monument status. Kudos to the preservationists!

LA Art Show—coming soon! Art Fairs Return

And they’re baaack! The LA Art Show had to back out of its usual January slot, but it has rescheduled itself into the LA Convention Center for July 29–August 1. They’re billing a “European Pavilion,” which I’m looking forward to seeing. https://www.laartshow.com/

The Felix Art Fair is also returning that same weekend, and to their old venue, the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel. This time they’re taking up only the first floor “cabanas” around the pool and focusing on just 29 Los Angeles galleries. Get your tickets early for this one—it’s always crowded. https://felixfair.com/

-

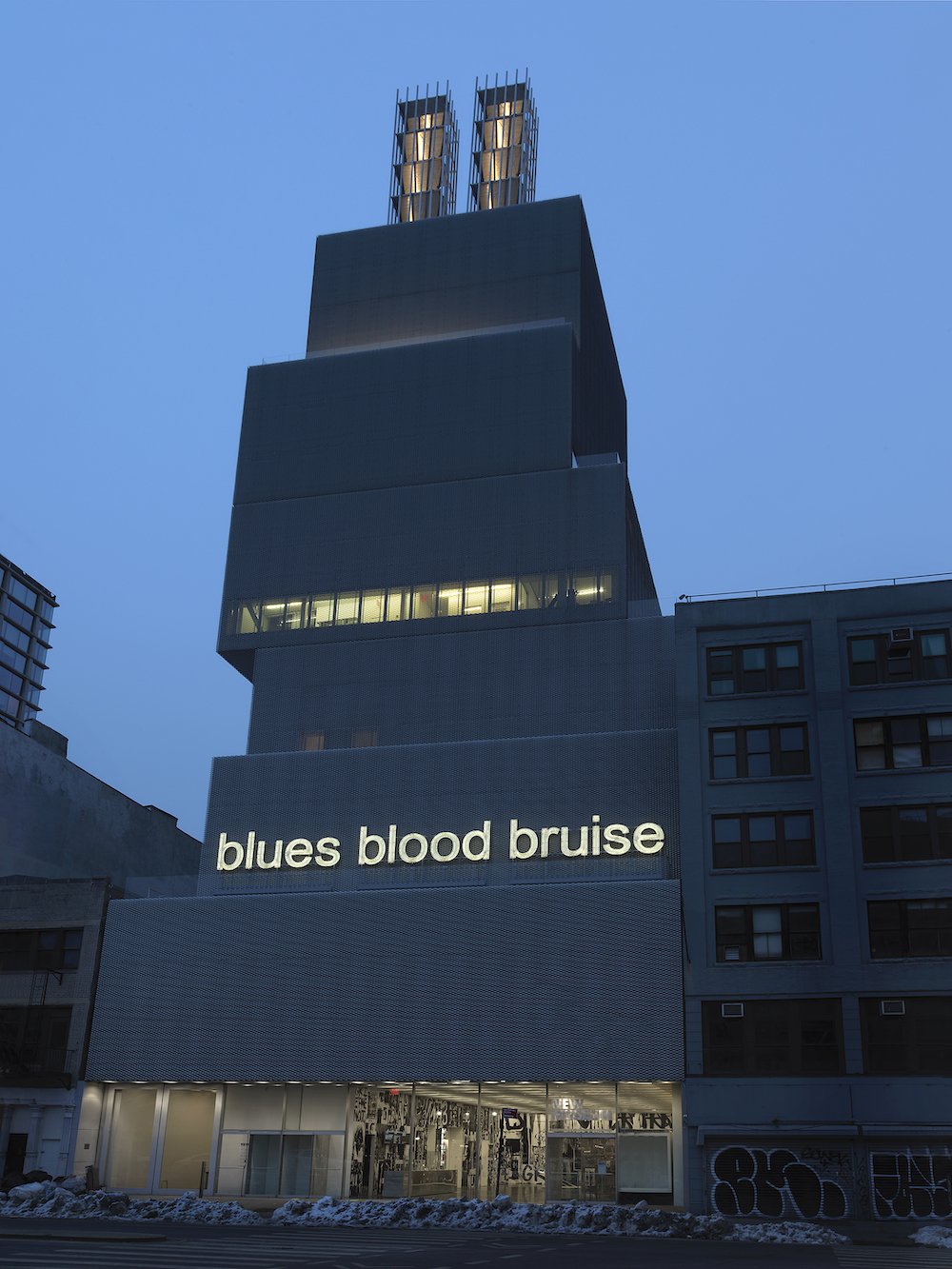

Black Grief Examined at New Museum, NY

“Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” By Okwui EnwezorGrief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, 2020

By Okwui Enwezor

264 pages

Phaidon/New Museum, New York

In a pivotal scene in Francis Ford Coppola’s film The Godfather a Mafia don grieves over the body of his dead son. “Look how they massacred my boy,” the weeping father intones, and the audience grieves with him. A worldwide audience is moved by the pantomime death of a handsome movie actor.

Another dead son, this one truly dead and made so just a few years after the theatrical death, is viewed in an open coffin. He is just a boy, and he is disfigured, gruesomely distorted. He is missing an eye, he is swollen, and he is, was, real. Upon the perpetrators there is no comeuppance visited. There is no justice.

“Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” 2021. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni In Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America—a piercing title that recalls the Reagan era—the late author and curator Okwui Enwezor had envisioned an exhibition where writers and artists excavate, examine and enliven the antithetic of Black and America. His death at age 55 prevented his completion of the project but it has been dutifully and beautifully realized by Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Ligon and Mark Nash.

Tiona Nekkia McClodden, THE FULL SEVERITY OF COMPASSION, 2019 in “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” 2021. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. The book by Phaidon and exhibition at the New Museum feature the work of essayists and artists whose work is both moving and haunting. Considering the historical similarities between Black deaths in the antique and the contemporary, Saidiya Hartman, in her essay, Dead Book Remains, conflates the horrors visited on past and present Black bodies as being something to be expected; that while their labor may have value their personhood does not. In My Soul Looks Back in Wonder Naomi Beckwith records the evolving status of images of negritude, from persecution to resistance, and specifies how the co-option of Black pain as seen in the Whitney Biennial’s choice of artist Dana Shutz’ Open Casket (2016) painting of the decomposed Emmett Till was so cack-handedly considered; a throwback souvenir for unreconstructed white folks, like baseball manager John McGraw’s lynching rope souvenir, or dreadlocked ski-bums in Vail.

The artworks featured include The Full Severity of Compassion (2019) by Tiona Nekkia McClodden, a fully blackened cattle squeeze chute, suggestive of bodily coercion, experimentation and consumption. Similarly haunting is Drainer (2018) by Julia Phillips, a ceramic cast of a woman’s torso suspended above a concrete shower drain, a peculiar bodily dissection of unknown or willfully dismissed history.

Julia Phillips, Drainer, 2018 in “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” 2021. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Many of the artists included are so widely known that their contributions become less powerful. Celebrity transforms their work into spectacle, clouding the visceral bite they might otherwise convey. The majority of works and essays, however, reach deeply into our sensibilities, insisting that we either embrace or dismiss, to vehemently choose sides.

Yet the rise of righteous protest and demand versus the naked and eager retaliation that it faces has not prefigured a concluding détente but a death spiral of the republic, suggesting that any hope of equity will ultimately devolve into a tense and simmering stalemate.

-

Reconnoiter: Kimberly Brooks

Interview with the artistThe acorn never falls too far. At age 12, an enterprising artist stood in front of White on White, the Kazimir Malevich painting at MoMA NY. She tugged on her father’s sleeve and asked the surgeon, “What does it mean?” His answer inspired Kimberly Shlain Brooks toward a career in the arts. Her question sent Leonard Shlain on a decade-long inquiry which produced the 1991 bestseller, Art & Physics. Shlain dedicated his studies to the art of science; his daughter focused on the science of art. Her new illustrated book, which reveals safe practices for oil painters, may revolutionize the popularity of the once-hazardous medium.

ARTILLERY: You are a busy practicing and exhibiting artist. How long have you been painting and where has that taken you?

KIMBERLY BROOKS: I started painting when I was in college, spending the first five years painting the figure. I have moved through so many phases since then, from portraiture to landscape. As I enter my 30th year with the medium, I am flirting with abstraction. I have an exhibition this summer at Zevitas Marcus in Culver City.

Beyond the title of your new book, The New Oil Painting: Your Essential Guide to Materials and Safe Practices, what can we learn?

I think oil painting is one of the most misunderstood of all the art materials, the diva of all mediums. Most people think they need solvents. This, among other reasons, causes many artists to opt for acrylics. I longed for a little black book on oil painting, a basic understanding that had everything I needed to know, about the materials, as I use them. I conferred with scientists, conservators and historians. I wanted to make it easily accessible, so I illustrated it with drawings, and thanks to Chronicle Books I have color photography as well.

What prompted your research? How far did you investigate?

I used to have a studio in Venice. One hot day, when I had been painting with all the smelly stuff, I suddenly had trouble breathing. It really freaked me out. I knew I had done some kind of damage, but I didn’t know how long it had been brewing. I then spent the next year trying every other media on earth to see what would satisfy me. Nothing measured up to oil painting.

How far did I investigate? Exhaustively. I ultimately learned that you really don’t need all those fancy, toxic things. An experienced oil painter may balk. Hopefully that person will get the book and discover how beautiful and simple oil painting can really be if it’s used the way science, not history, recommends.

Photo by Stebs Schinerrer Acrylic or oil? Your thesis challenges the choice most artists have made. Thoughts?

Definitely oil. I think acrylic can be fine for very geometric work but I don’t like the way it dries so flat and fast. For me, it is not as sensual.

All of your many projects are redefining the term “synergy.” What is First Person Artist?

First Person Artist is an interview platform where I talk with notable artists and we answer questions from the audience. During the pandemic, I started hosting “Fireside Chats” and “Vampire Cocktail Hours,” where we gather to look at art online. If any readers are interested in attending the next event, they can sign up at Firstpersonartist.com.

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Naotaka Hiro

The BoxTwo side-by-side paintings face the gallery’s front door, awaiting visitors like sentries. They have all the elements that characterize Naotaka Hiro’s “Armor” exhibition, namely colorful swatches and fervid mark-making that expands from a vertical center line. The frequently butterflied compositions as well as abstracted renderings of fingers clue viewers into Hiro’s anatomical inspiration and process.

In the main gallery, visitors are again met by two side-by-side paintings, these nearly floor-to-ceiling on raw, unstretched canvas. Two large circles are cut out of each one. The holes allowed Hiro to insert himself through the canvas, ball it around his upper body and over his head (imagine a canvas dumpling with human legs) and proceed to dye the piece from the inside. Then he came out of the cocoon and worked from what he’d blindly started.

Installation view, Naotaka Hiro “Armor” at The Box, 2021 The artist employed a similar process for the exhibition’s central body of work, six 8 x 7 feet freestanding paintings on plywood. Each piece began laid flat, with short legs attached like on a coffee table. Hiro slid under the “coffee table” and, lying on his back, painted the underside, loosely tracing himself. He often worked with both hands. Then he flipped the piece over and worked sitting and standing on top of it. He then repeated the process until all the binaries blurred. The six paintings are arranged in a horseshoe, with a bronze cast of the artist’s torso (primarily) positioned before them.

Installation view, Naotaka Hiro “Armor” at The Box, 2021 The gallery’s back wall dazzles with ten 58 x 42 inch paintings on wood, focused on parts of the body rather than the whole. One has hand-sized holes cut out, suggesting another blind painting technique. Around the corner, a second bronze torso—this one more skeletal—ushers visitors into a screening room with a video of the artist at work. Beside that is a room of the artist’s sketches.

Installation view, Naotaka Hiro “Armor” at The Box, 2021 “Armor” presents process-oriented work about the body inspired by the COVID-19 pandemic (Hiro contracted COVID early on) and concurrent American socio-political upheaval, including attacks against Asians. The work, however, stands on its own visually and will continue to do so beyond this historic period.

Naotaka Hiro: Armor

May 29-July 24, 2021

All images ourtesy of the artist and The Box LA. Photographs by Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

-

Outsider Art Fair & Takashi Murakami

“Super-Rough” Group Show, New YorkOutsider art is on display in full force in SoHo with a special exhibition hosted by the Outsider Art Fair and curated by Takashi Murakami. Focusing solely on sculpture, the exhibition brings together works by nearly 60 Outsider artists, a term that generally refers to artists who are self-taught. The exhibition is titled Super-Rough, a play on the term “superflat” that was coined by Murakami and refers to a style characterized by flatness and inspired by Japanese consumer culture, including manga and anime. Refreshingly unfiltered, the works in the show offer an imaginative exploration of materials, colors, and forms.

Installation view with works by Ryuji Nomoto and Yasuhiro Hirata, Yukiko Koide Presents. Upon entering the expansive exhibition space, I was confronted by a monumental, raised platform rife with sculptures that were anything but flat. While a few larger installations and wall pieces hung along the sides of the room, the vast majority of the nearly 200 sculptures were on this center platform. Abandoning the traditional art fair arrangement in which works from different dealers are separated into distinct sections and booths, the sculptures were all displayed together, allowing for close comparison of each piece. Also a departure from the art fair model, the exhibition is on view for nearly three weeks, running through June 27th and allowing for more time to visit.

Installation view with detailed view of works by Ryuji Nomoto and Yasuhiro Hirata, Yukiko Koide Presents. In line with the title Super-Rough, there were many artists who explored the physical boundaries of their materials. Displayed next to each other, artists Ryuji Nomoto and Yasuhiro Hirata, both from Japanese gallery Yukiko Koide Presents, are two memorable examples. In Nomoto’s untitled sculptures, the artist created colorful mounds that at first appeared to be wild bundles of string, but were actually made of colored glue. Piled into amorphous shapes, the works looked like they were slowly moving, as if pushing off of their wooden bases. Installed next to these was a cityscape of colorful cylinders by Hirata. All titled Corn on the Cob (2005-2020), Hirata’s sculptures, which looked to me like perfectly crafted ceramic vases, were a range of sizes and covered in small dots. Upon closer inspection, I was surprised to see they were actually made of paper tubes painted with acrylic. Even more surprising were the dots across the surface, which were not dots at all, but rather steel nails that the artist hammered into the tube, seen more clearly when viewed from the open sides.

Installation view with Paul Amar, Galerie Pol Lemétais and Gil Batle, Ricco/Maresca Gallery. Further down the platform was an assortment of glittery, colorful figures by Paul Amar. Playful and highly detailed, the figures resembled small altars and were made entirely of seashells. Next to Amar’s sculptures were pieces by Gil Batle that defied materials even further. Though they appeared to be stone, they were actually carefully carved ostrich eggshells with details so minute that a magnifying glass was provided for a closer look. Pairing the two artists together, I was struck by how they masterfully manipulated the unexpected material in such different ways.

Overall, the sculptures in Super-Rough were interactive, imaginative and playful. Having just viewed an exhibition of highly academic, critically acclaimed drawings at a nearby gallery, I was amazed at what artistic production free from stylistic and academic pretense could look like. It was refreshing reminder of how genuinely surprising art can really be.

Outsider Art Fair “Super-Rough” Group Show

Guest curator: Takashi Murakami

150 Wooster Street, New York

June 9-27, 2021

All photos by Annabel Keenan.

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Rebecca Campbell

L.A. LouverThe radiant and complex paintings in Rebecca Campbell’s exhibition “Infinite Density, Infinite Light” draw from the past, yet are very much about the present. They explore the nature of family, the freedom of being a child and the fragile nature of memory. Using found images including family snapshots and Polaroids, Campbell transforms isolated moments into stories about the people in her life— be it her children or parents. Within each work, she uses different painting styles to create an evocative journey through her own history.

Although the exhibition is predominantly a show of paintings, Campbell also includes a sculptural installation in the center of the gallery that directs the interpretation of the works. Titled To the One I Love the Best (2017), this mixed-media piece consists of a collage of translucent silk banners suspended from copper piping. They contain enlarged reproductions of concert tickets, a Western Union Valentine’s Day Telegram, handwritten letters and other documents that span different periods in Campbell’s family’s life.

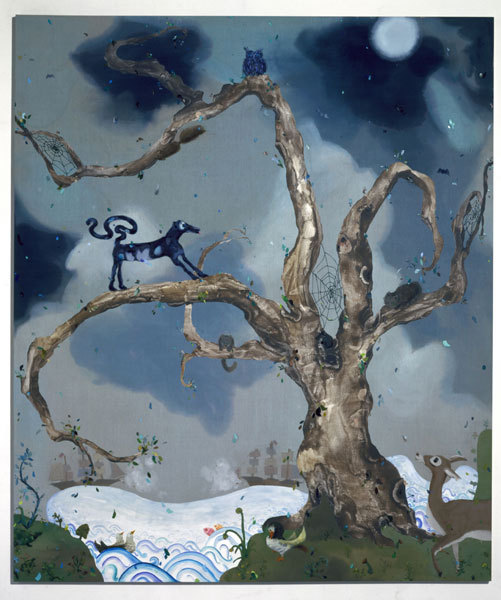

Rebecca Campbell, To the One I Love the Best, 2017, installed in Rebecca Campbell: Infinite Density, Infinite Light, L.A. Louver In her paintings, Campbell often juxtaposes realistically rendered areas with looser, more abstracted brush strokes and thicker applications of paint. These gestural markings create a dream-like sensation that suggests the passage of time as evidenced in Nature Boy (2021), a large painting of Campbell’s son in the woods. The boy wears a white T-shirt with red letters that spell the word LOVE and holds a single plant stem. Behind him is an inkling of a path that leads to a giant tree trunk painted abstractly with swirling strokes in a range of soft colors. Campbell’s mélange of styles enhance a narrative that weaves past and present, dream and reality. The setting is simultaneously peaceful and unsettling as the child’s expression is one of defiance and awe.

Most of the paintings in Infinite Density, Infinite Light challenge the idea that there is a straightforward narrative about family: children growing into adults, having children of their own and negotiating the wonders of life. While Campbell depicts her subjects with compassion, at times she places them in potentially ambiguous situations interrupting what is represented in the original photographs with an abstract overpainting that suggests a divergent trajectory. In this exhibition, Campbell invites viewers to bear witness to her personal journey, while simultaneously suggesting it could resonate universally.

Rebecca Campbell

Infinite Density, Infinite Light

L.A. Louver

May 24 – July 2, 2021

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Patrizio di Massimo

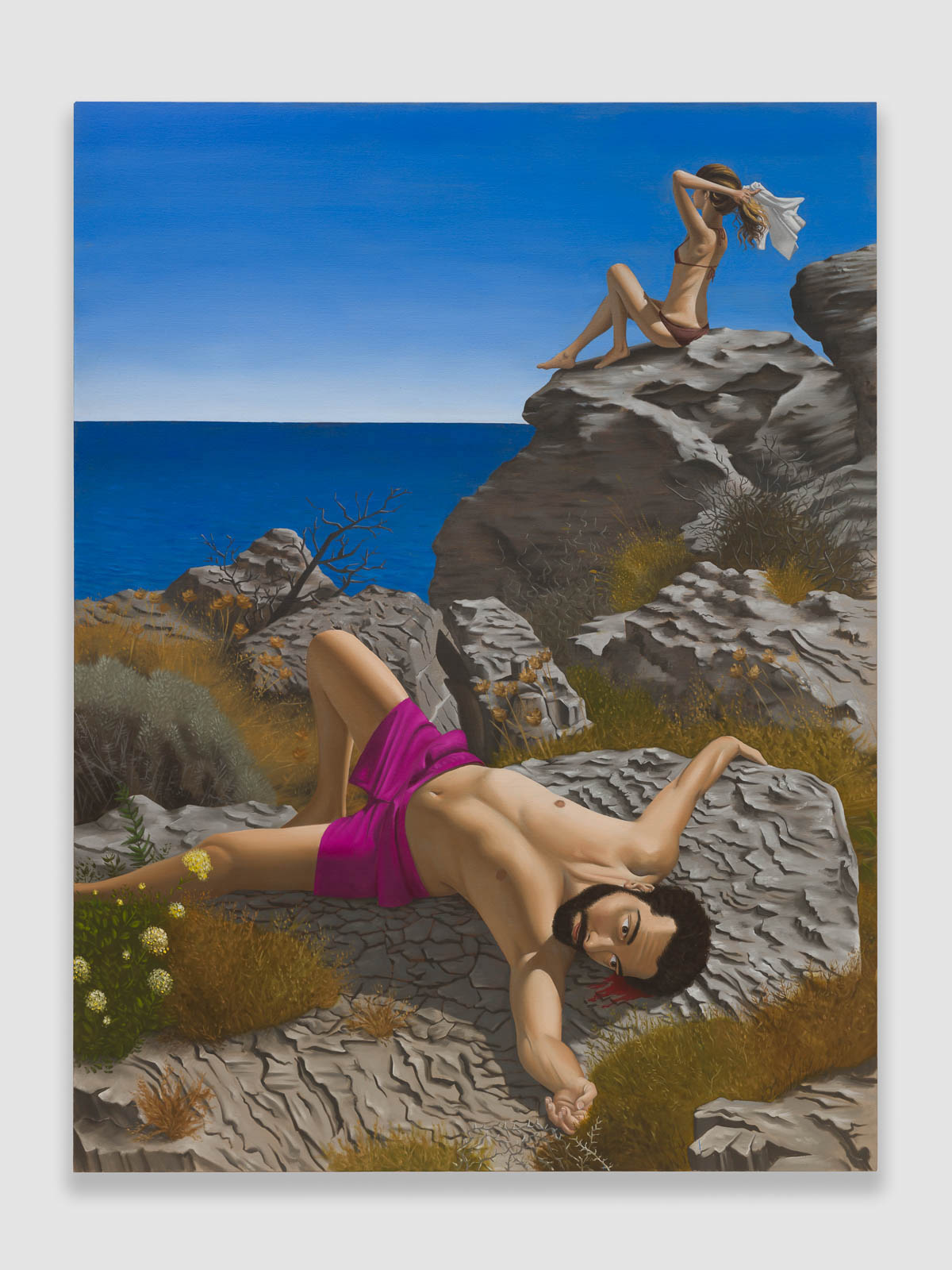

François Ghebaly GalleryLike Schrödinger’s cat, the figures populating the canvases of Italian painter Patrizio Di Massimo’s paintings exist in two potential states at once. In his newest exhibition, Close at Hand at François Ghebaly Gallery, time/space freezes in each of the five paintings on view, creating a pseudo quantum superposition. There is an antagonist and protagonist in each melodramatic mise-en-scène—the antagonist caught ‘red handed’—their deeds immortalized in paint. Unsettlingly it is up to the viewer to decide the final resolution of the narratives.

For one example, in the painting Mum’s Floral Robe (2020) two figures are suspended in a state of struggle at the pinnacle of action/reaction. A female figure leans over a sofa, grabbing the “mum” in the scene by the scruff of her robe. The antagonist female figure also has her hand suspended in the air, as the mother screws up her face in theatrical terror. When initially viewed, this appears as the millisecond before a violent act. Yet when scrutinized further, the faces seem comical and playful, as if they’re only play fighting.

Patrizio di Massimo, The Island, 2020. Two bathing-suit-clad figures inhabit The Island (2020). A man lays seemingly dead at the forefront of the painting, splayed on a rock face, his arms opened at awkward angles and red blood pooling underneath his head. A woman is perched unabashedly above the man on a cliff and facing the ocean—she removes an article of clothing while basking in the breeze and brilliant sun. The discontinuity between the figures make the viewer wonder how connected they are? Is this the moment immediately following a vicious murder, or is the woman basking in blissful ignorance?

Installation view, Patrizio Di Massimo, Close at Hand, 2021, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles As stated in the press release the series was “completed over the course of fluctuating waves of lockdown… [and] shows the unruly side of intimate vicinity, especially when imposed under duress.” Each paintings offers more questions than answers. As indicated by the name of the show, the hands of each character in the paintings offer an implied theatricality which suggests a mock-reality, humorously representative of one of the oddest years in recent memory.

Patrizio di Massimo: Close at Hand

May 22 — June 19, 2021

All photographs by Paul Salveson. Courtesy of the Artist and François Ghebaly Gallery.

-

GALLERY ROUNDS: Emil Alzamora

Lowell Ryan ProjectsEmil Alzamora’s “Waymaker” is like journeying through a series of time warps. Cement, steel and wood figures loom in various states of decay like Greco-Roman relics in a museum. Yet a modern sensibility invites the sculptures into a surrealist dream conjuring a restrained body, mangled by metal. His sculptural figures are caught in a violent tempest of industrial materials that weave in and out of linear time.

Emil Alzamora, Wormhole at Cladh Hallan, 2021 Wormhole at Cladh Hallan (2021) gives us a clue as to how Alzamora considers the body’s narrative history. Cladh Hallan is reportedly the only place in Great Britain where prehistoric mummies have been excavated. By alluding to a wormhole, Alzamora plays with the limits of time. He casts a dramatic resurrection by reconstructing forms out of rubble. His inventions are kin to Mesopotamian lamassu, a divine hybrid of human and animal. In Alzamora’s case, he unites the materials most commonly used in construction to introduce the human/industrial hybrid. He leans into the construction process through additive and subtractive techniques to highlight the procedure of the build.

Emil Alzamora, Hone Redux, 2018 Surrealist psyche unshackled, Alzamora’s sculptures stand among the fluid and powerfully charged sculptures of Umberto Boccioni. In fact, his provocative and alluring forms far outweigh any conceptual fodder. A practicing sculptor since the late ‘90s, Alzamora is a master craftsman when it comes to design. From the aquiline arms of the figure in Star Suit (2018), to the pocketed seams along Hone Redux’s (2018) ribs, Alzamora captures the ambition and drama of Henry Moore’s work while maintaining sensitivity to subtle expression. The arched back and exaggerated neck of Waymaker (2021) imitates Persipine’s deserpate clamor for freedom in the Baroque marble sculpture The Rape of Proserpina. Likewise, Hone Redux bears striking resemblance to the ancient Crouching Aphrodite and Crouching Venus sculptures. No doubt Alzamora was stuck with inspiration from the ancient world and his industrial time warps tunnel us into a futuristic dystopia studded with impeccable design.

Emil Alzamora “Waymaker”

May 8 – June 19, 2021

All photographs courtesy of the artist and Lowell Ryan Projects.