John Knuth is a Los Angeles-based artist who recently had a solo show with Hollis Taggart Gallery in Southport, CT. His work explores how humanity and material and the natural world intersect and influence each other. “The Dawn” ran from May 15–July 3.

MATT STROMBERG: From its title, the show has an unmistakably optimistic tone. what makes you hopeful? is it for a return to pre-pandemic life, or the possibility of a new way of living?

JOHN KNUTH: Yep! The show is conceived around the idea of rebirth. We have been in pupation quarantine for the past year. The vaccines are rolling out and we are emerging like brood X cicadas! I feel it. I think we all feel it.

I caught covid in August and it hit me harder than I think I realized at the time. I had lingering brain fog for about six months. Something changed in me after the vaccine and I have a renewed engagement, inspiration and outlook.

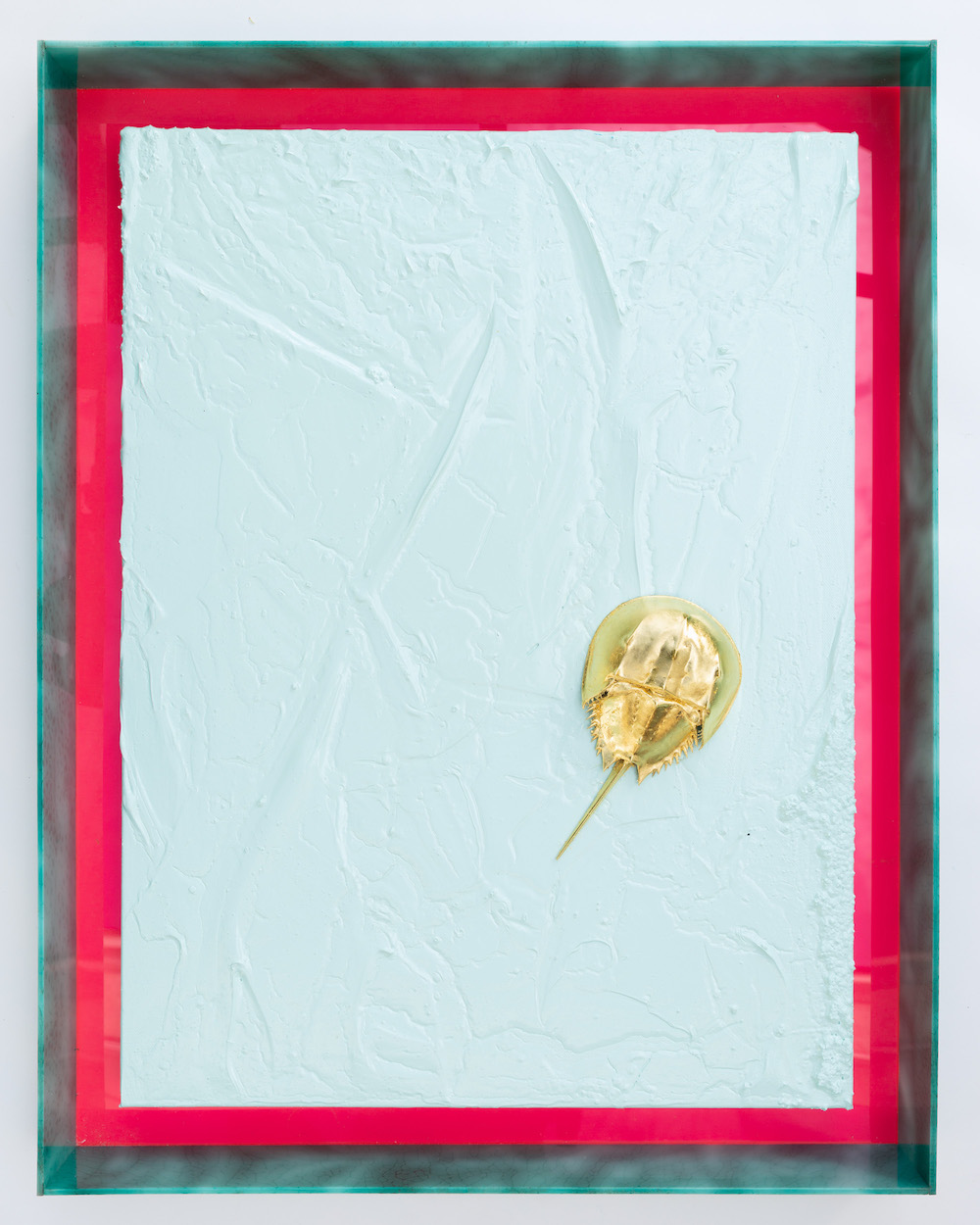

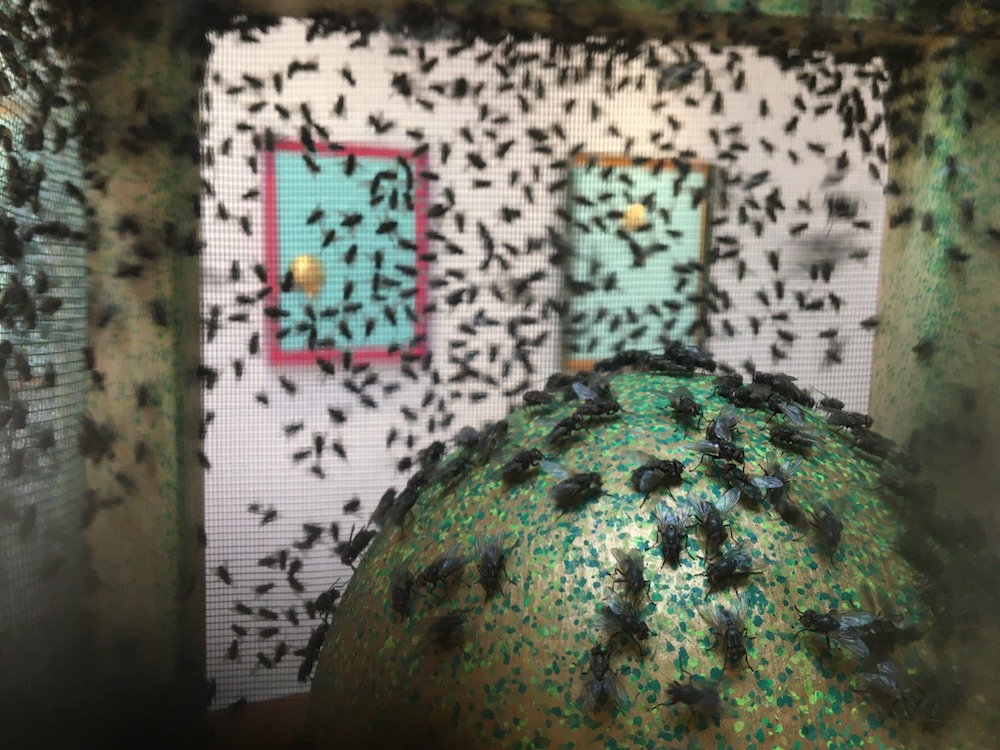

“The Dawn” became the theme for the show. All the colors and compositions for the fly paintings were made with the sunrise in mind: Yellow, oranges, reds, blues and metallics. I added ostrich eggs as a symbol of rebirth and an acknowledgement of the spring. I also added gilded horseshoe crab paintings and turned them into icon paintings celebrating the importance they play in our vaccines.

Installation view “The Dawn.” Photo credit: Ian Byers-Gamber

There’s an element of sacrifice in your work, whether in the form of the flies who live their whole lives just to make your paintings, or the horseshoe crabs who give their blood to make vaccines. Is that reflective of the kind of religious upbringing you had in Minnesota?

There are certainly religious themes that are in this show. I gilded horseshoe crab shells with 22 karat gold leaf to turn them into byzantine icon paintings. Horseshoe crabs are instrumental in our vaccine production and most intravenous drugs. Each spring on the east coast, thousands of horseshoe crabs are harvested and milked for their bright blue blood to be used in testing in pharmaceuticals and specifically vaccines. That’s because these animals’ milky-blue blood provides the only known natural source of limulus amebocyte lysate, a substance that detects a contaminant called endotoxin. If even tiny amounts of endotoxin—a type of bacterial toxin—make their way into vaccines, injectable drugs, or other sterile pharmaceuticals such as artificial knees and hips, the results can be deadly. Without putting it too lightly their blood gives us life. I also thought of these paintings as my Warhol Marylin Monroes. Or refocusing the idea of the religious icon painting—Of course the idea of the egg is a symbol for Easter and rebirth.

I’d say the influences of my childhood are certainly throughlines in this show. I grew up on a creek catching snakes and turtles and going to church with my family. I also grew up reading Warhol books. So it is all a part of the thinking in this work.

John Knuth, Horseshoe 1. Photo credit: Ian Byers-Gamber

Where do you get the horseshoe crabs from?

I originally wanted to paint with horseshoe crab blood, but no one would sell it to me. It costs $16,000 a pint! I was trying to buy even just an ounce but the companies that harvest and sell it to pharmaceutical companies would not sell it to me. (I should note that no horseshoe crabs were harmed in the production of this show. They have exoskeletons and they shed their shells, so people collect them and sell them online.) You can purchase anything online. In the past year I have purchased rattlesnake venom, a million maggots, ostrich eggs, horseshoe crab shells etc… How do you see artists responding to the Covid-19 pandemic? You see much more art than I do. I don’t know if I have really seen any art that is directly about it yet.

It’s a good question. lots of artists’ recent work has been shaped by the pandemic. You’ve all been alone in your studios, with nothing but your thoughts to keep you company. No students (in person at least), no collectors to schmooze, no fellow artists to connect with. Even if the art is not directly about the pandemic, its about loneliness, alienation, apocalypse. Or engaging with the idea of a reset, that we just go back to “normal” after the pandemic, but we need to actually think about what’s important, how we want to act and live after this cloud lifts. The dawn right? The new dawn, rebirth, the egg. its not about status quo, it’s about a new world.

Installation view “The Dawn.” Photo credit: Ian Byers-Gamber

You go and see exhibitions multiple times a week. How has the pandemic and now the vaccine roll out changed your feelings of seeing shows?

To be honest, i never felt unsafe at galleries, even during the middle of the pandemic. Like they were never really that many people at a gallery in the before times. I felt much more anxious at Costco, with scores of people pressing up on you, chin-masking it. Now I feel downright gleeful to be in a gallery. There’s been a funny thing over the past month or so where I’ll go to a gallery, generally a smaller storefront gallery, with my mask on and the gallerist and I lock eyes, and we both take our masks off, since we’ve both been vaxxinated. Its a small intimacy, a show of confidence, of trust. which is quite rare in the art world.

Are you looking at art differently in a vaccinated world?

Taking a break from gallery-going has only made me appreciate seeing art in person so much more. It is a social and physical activity. I rely on instagram and social media to keep me updated, discover new work, share what I like, but it’s not a replacement. Art is a physical thing (unless of course when it’s not), but there’s a smell, a dance you do around objects, even paintings, that doesn’t translate to the screen. Thankfully we had a way to keep us connected and inspired throughout the past year, but as long as artists are picking up a brush, or a lump of clay, or even setting up a fly pen to make work, then we need to see it in person, there’s no alternative.

Installation view “The Dawn.” Photo credit: Ian Byers-Gamber

Agreed, it is wonderful to be back in front of the physical objects. I guess my question is more of an emotional or if how you are thinking about art has changed? For instance, I went to the Norton Simon the week it opened back up. It’s a place my wife and I love to visit and it’s our stop to see some masterpieces and have happy hour in the garden. We took our one-and-a-half year old son to see his first art museum. I could tell he was connecting with the paintings. We look at a lot of art books at home together. But when we were in front of Eduard Manet’s Ragpicker, Mateo seemed to connect to the painting. It was quite an emotional experience for me. I think with the incredible homelessness issue in LA and missing a connection to humanity the painting changed for me. I was so touched that Mateo was reaching out and emoting towards the painting. I didn’t expect to be so deeply touched by the experience. Mateo’s reaction and my empathetic experience of that painting in that moment will be a treasured memory.

Mateo at Norton Smith. Photo credit: John Knuth

That’s a sweet story about your son, what do you think it was about the Manet that he connected with? Usually when our kids are drawn to figurative work, it’s because the subject looks like someone they know, they can relate it to their own lives. When we’ve taken our kids to the museum, I see them connect more with the physical experience of being there than with the images per se. Like seeing Burden’s Metropolis 2 at LACMA—which is obviously a kid favorite because it’s just a giant race track with dozens of toy cars and trains—it still couldn’t compare to the actual construction going on outside on Wilshire Boulevard) or Nikita Gale’s Private Dancer at CAAM, which is basically a theatrical lighting truss on the ground, with lights flashing and spinning, programmed to coincide with a silent version of Tina Turner’s “Private Dancer.” They couldn’t get enough, running all around it, chasing the lights. What it really drove home for me was the embodied experience of viewing art; these are social spaces where we encounter objects, not just images.

Stromberg’s kid in front of Metropolis II, Photo by Matt Stromberg

Which circles back to your work I think, because it’s not just about image creating, but these are objects you’re creating, even the fly paintings have a complex, built-up surface (and a smell!) that doesn’t quite carry through on the screen. And then your decision to incorporate actual horseshoe crabs instead of representations, and the neon plexi which can never quite translate in a photo.

Another stray thought is that as much hope is embodied in your new work, the horseshoe crab as a symbol of science’s mastery over illness, they’re also a bit of a momento mori. The horsehoe crab has been around for hundreds of millions of years and will likely be around after we’ve made ourselves extinct. Some future alien race will find your gold painted horseshoes in their plastic frames (which will most likely not degrade for hundreds of years), and perhaps think it was a portrait of a notable crab painted by a crab artist, with humans never entering their reconstructed narrative. It’s similar to the Ragpicker in a way, the lowliest of the low, whom we walk by and ignore. But the canvas that Manet is painting on will presumably one day just be another pile of rags for another ragpicker to collect and sell to eek by.

I think much of this conversation goes back to Manet or Courbet and Realism who Manet certainly comes out of that lineage. Maybe not as a painting style but as way of approaching art or thinking or making. I think of myself as a realist artist meaning I try to engage with the world, and make artwork that is involved in the world not romantic, not escapist, not nostalgic, not art about art. I make art of and about the world. It is important that the horseshoe crab is real and that the gold leaf is real and not gold paint. It is not a representation it is the real thing. In our vaccinated world this impulse to participate and experience is even stronger.

John Knuth was born in 1978 in Minneapolis, Minnesota and lives and works in Los Angeles, California. He received an MFA from University of Southern California and a BFA from the University of Minnesota. Knuth’s recent solo exhibitions Powerplant at Brand New Gallery, Milan, Italy; Base Alchemy at 5 Car Garage, Santa Monica, CA; Master Plan at Andrew Rafacz Gallery, Chicago, IL; Elevated Uncertainty at Marie Kirkegaard, Copenhagen, Denmark; and Fading Horizon at Human Resources, Los Angeles, CA. His works has recently been included in group shows at International Print Center, New York, NY; Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY; MassArt, Boston, MA; Self-Titled, Tilburg, NL; Los Angeles County Museum of Art in Los Angeles, CA; and the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Matt Stromberg is a freelance arts writer based in Los Angeles. He contributes to a range of publications including the Los Angeles Times, Hyperallergic, Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles, The Guardian, The Art Newspaper, KCET Artbound, Terremoto, Artsy, frieze, and Daily Serving.

Editor’s note: This dialogue took place early July, before the resurgence of COVID19 (again).