We can never cover all the deserving women artists in one issue, so in a modest gesture, we asked our writers to pitch a woman artist they’d like to champion in 200 words, to squeeze in just a few more.

Gala Porras-Kim

The sprawling, splintered and paradoxical poetics used to describe Los Angeles are evoked in the work of Gala Porras-Kim, each bubbling with alternatives ripe for excavation. Porras-Kim rearranges and reframes cultural artifacts, objects and documents to unhinge and de-center the heterogeneous modernist subjects that have long dominated museum practices and shape the so-called “cultural mainstream.” While her work is not confined to subjects and institutions in Los Angeles, this city lends itself to the motivations underlying Porras-Kim’s practice that promote expansive representations of identity and cultural heritage. For most of the 12 million people of the greater LA area, it’s nearly impossible to avoid feeling the tensions of day-to-day life in a city segregated by design and oriented around shifting modes of capitalism in an increasingly globalized world. Porras-Kim prioritizes the many “other” lived experiences and embodied histories that have been marginalized or omitted from institutional discourse.

Porras-Kim’s practice serves as a vital reminder that this work will never end—nor should it—because as arbiters of knowledge and culture, museums must remain expansive and malleable to allow for new systems of care, representation and learning to occur. Her work emerges from the challenges embedded in LA’s cultural landscape and the city’s legacy of artists and alternative practices that continue to push art and institutions forward.

––Lauren Guilford

Gala Porras-Kim, photo by Paul Salveson, 2021; courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles and Mexico City; ©Gala Porras-Kim.

Gala Porras-Kim, A terminal escape from the place that binds us (installation view), 2021. Photo by Paul Salveson, 2021. All images courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles and Mexico City. © Gala Porras-Kim.

Eileen Cowin

Throughout her 50-plus-year career, Eileen Cowin has created enigmatic and beautifully sequenced multi-panel photographs and single-channel, multi-channel video installation works, in addition to large-scale public art projects. Cowin’s emotionally charged imagery is narrative-based and often draws from literary or news sources, yet in Cowin’s worldview nothing can be taken for granted. She exults in the unexpected, be it a photograph of an urban deer caught in the headlights—a metaphor for lost innocence and hesitation—or a multi-panel narrative like her newly commissioned photo-narrative: “You are heading in the right direction,” installed in the Martin Luther King Jr. station of the Metro Crenshaw/LAX line, which invites viewers to imagine the lives of the people depicted in the pictures as they travel on the trains. Cowin’s dreamlike images are simultaneously fantasy, fact and fiction.

In her recent works, meaning comes from juxtaposition, as in the differing expressions of loss in recent large-scale images of flowers set against black backgrounds. Cowin has created an expansive and thoughtful sequence of images that poetically address increased anxieties over the current political climate.

An astute looker and reader, Cowin analyzes personal and universal moments in her work, presenting the everyday as something extraordinary.

––Jody Zellen

Eileen Cowin; courtesy of the artist.

Eileen Cowin, Time of Useful Consciousness, 2014/2022. Courtesy of the artist.

Kristin Bedford

If we’re talking about LA women artists who are blazing right now, we’ve got to talk about photographer Kristin Bedford. Bedford spent 2014–19 exploring lowrider culture in East LA, greater Southern California and Nevada. The resulting series, “Cruise Night,” consists of color photographs as exquisitely saturated as a custom paint job on a 1964 Chevy Impala. Bedford photographed not only the cars, but their driver/creators (including many women), their tattoos and family snapshots with former vehicles. She also recorded oral histories, giving her subjects voice within the project. Never a gawker and hardly a motorhead, Bedford was interested in the personal and collective creative expression of this culture.

Italian publisher Damiani released Cruise Night as a photobook in March 2021. A #1 bestselling photobook on Amazon, it has since sold out—the lowrider community being a big part of that. In October 2021, Just Memories Car Club organized a Cruise Night book signing and car show at the Autry Museum, attended by over 1,000 people and hundreds of lowrider vehicles. Meanwhile, Bedford’s photographs have enjoyed international exhibitions—a rare appreciation for authentic LA outside the home ground. “Cruise Night” is at Galerie Catherine et

André Hug in Paris this November.

––Allison Strauss

Kristin Bedford taking photos by the LA River for the project “Cruise Night”; courtesy of the artist.

Kristin Bedford, No Soy De Ti/I Don’t Belong to You. Courtesy of the artist.

Penda Diakité

I am a long-time admirer of Malian-American artist Penda Diakité, whose work explores what it means to inhabit a body codified as both Black and woman.

So often, the bodies of Black women and femmes are relegated to categories that center only our productivity and usefulness: caretaker, laborer, birther. But in Diakité’s world, these reductive categories are deprived of their power. Through her mixed-media collages, Diakité reveals the many colors, textures, stories and memories that constitute Black womanhood. Her subjects are profoundly multidimensional, demanding the viewer’s earnest consideration, refusing monolithic classification. Viewing Diakité’s work, I feel my own complexities—my rough edges and tender vulnerabilities—avowed in mosaic splendor.

When speaking of her work, Diakité has said that she explores Black feminine identity as if “our soul’s experience was reflected in our appearance.” I am thankful for her willingness to tell the fuller richer truths of those souls, which are bursting at the seams with new stories to tell.

––Donasia Tillery

Penda Diakité, 2022, courtesy of the artist.

Penda Diakité, Mandiani, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist.

Andi Campognone

Andi Campognone began her professional career as an artist, creating photographs that compelled viewers to engage with—and participate in—her images. She transitioned into curatorial work, running two commercial galleries and serving as curator of the Riverside Art Museum. In 2011, Campognone became founding director of the Museum of Art and History (MOAH) in the City of Lancaster in the Antelope Valley region of California’s vast Mojave Desert.

While building innovative exhibitions at MOAH, Campognone has focused on collaboration and community building. She has partnered with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the LA County Department of Arts & Culture on projects intended to serve wider audiences. In 2014–15, for example, she worked with social-practice artist Suzanne Lacy and the LA Arts Commission on the “Antelope Valley Art Outpost.” The “placemaking” program used art and public practice as “tools to inspire development in the communities of the Antelope Valley.” Campognone remains a passionate advocate of connecting artists and government in problem-solving issues like the environment, sustainability and education.

In 2016, Campognone founded Kipaipai, an ongoing series of workshops and residencies for artists that supports career development and builds community. Kipaipai (“to inspire” in Hawaiian) has served artists throughout the US, sewing the threads of connection across the country.

––Betty Ann Brown

Andi Campognone at MOAH, 2021, photo by Marne Lucas, courtesy of Andi Campognone.

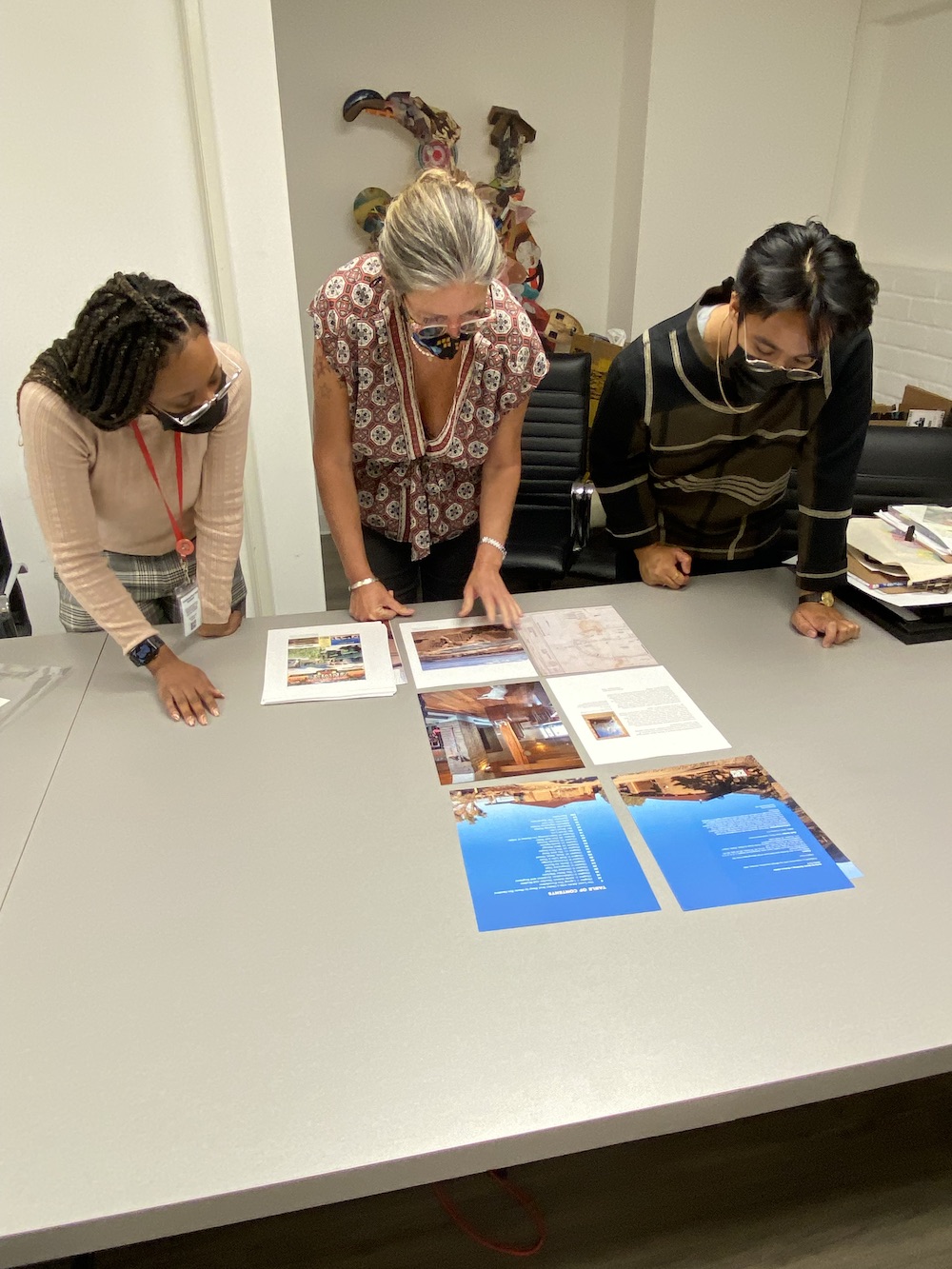

Andi Campognone working with curatorial staff at MOAH. Courtesy of Andi Campognone.

Samantha Fields

Samantha Fields’ paintings unfold along a darkly fanciful and increasingly multifaceted continuum of disaster and perception in storm fronts, fires, abandoned dreams and other metaphors for societal decline, mediated by uncanny photographic intercessions. She’s currently painting storms—their violent clashing and cleansing suits the era, and opportunities to expand her jewel-toned naturalism are many. She started on them

pre-lockdown, after photographing multi-tornadic phenomena in Texas. When everything changed—BLM, the lengthening pandemic, the insurrection, massive wildfires—she turned instead to the “American Dream” paintings: landscapes of winter’s discontent festooned in confetti and party balloons.

Recently, in Texas again, she photographed myriad storms which will be on view at Rory Devine Fine Arts in October. Her prismatic “Worlds Within Worlds,” based on dreamlike, anxiously shifting photos of her own backyard, were shown this summer at Berkeley’s Traywick Contemporary, and her affecting wildfire paintings are in two institutional shows this year. Along the way she became chair of the art department at California State University, Northridge—the first woman to hold the post—where she’s focusing on access, interdepartmental collaboration, and local and international exchanges. “When I came on board,” she says, “I kept asking, ‘Can I do this? Can I do that?’ and the answer was always, ‘You can do whatever you want.’ So, hell yeah, let’s do all the things!”

––Shana Nys Dambrot

Samantha Fields, courtesy of the artist.

Samantha Fields, If You Lived Here, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.