New portraits and still lifes by Mònica Subidé channel the aesthetic of circa-1906 Paris and Barcelona with such organic authenticity that they could credibly pass for recently discovered works by an unknown genius of that era’s avant-garde—yet they are imbued with an urbane air that belongs to the present. Stylized in a schematic mode that deploys nearly abstract shapes as elements of image, her portrait subjects’ physical aspects, such as hair, facial features and anatomy—as well the garments, adornments and furnishings that surround them—are all rendered with strong, minimal lines containing chromatic pieces like the solder in stained glass.

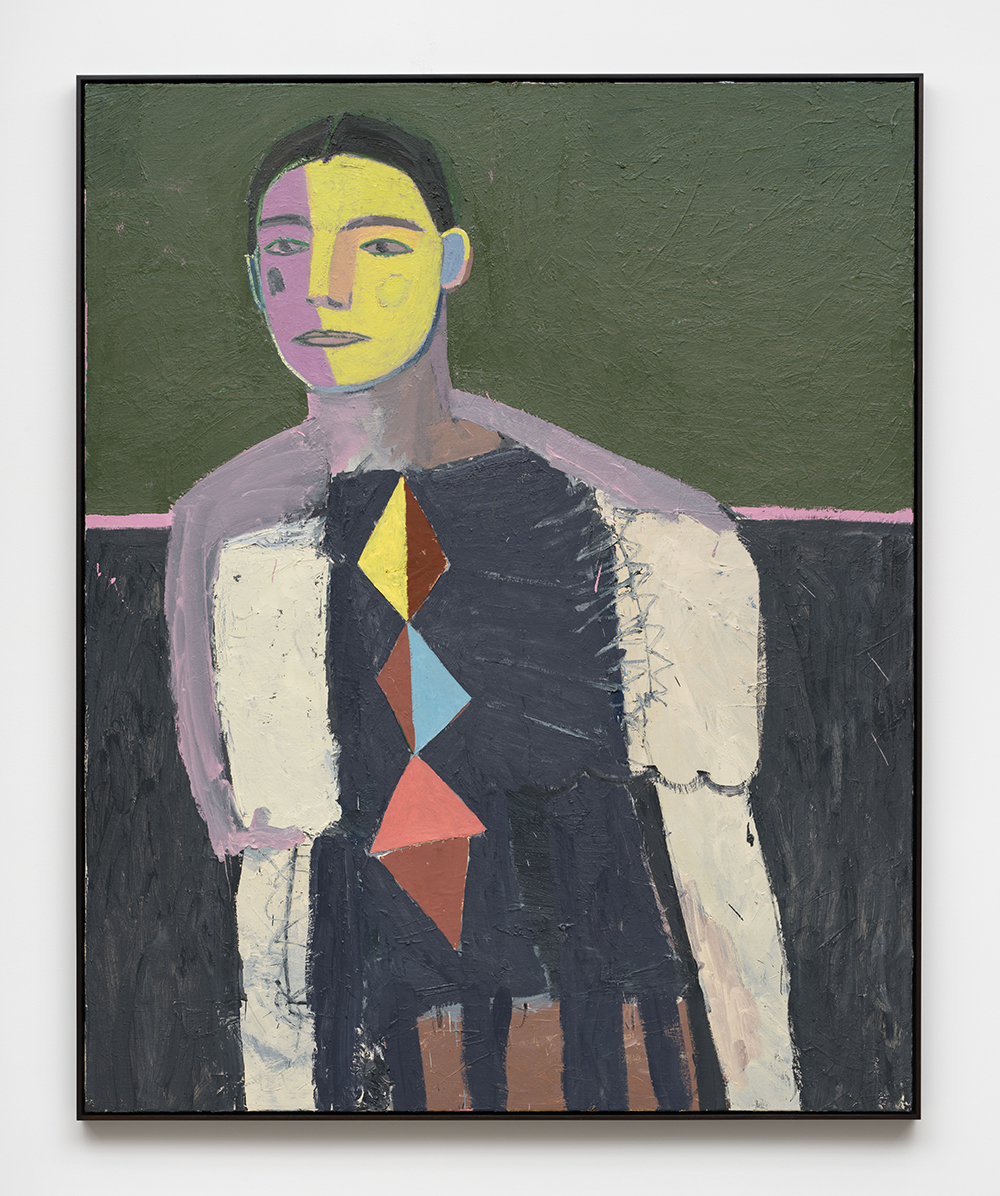

The evocation of Picasso is intentional and well met, fluently speaking the language of lofty arched eyebrows, aquiline noses flanked by pure color, bone structure by means of planar color forms, and chunky flowers in flat-fronted vases. Further, Subidé’s The red ear (2023) expresses its melding of physiogonomy with abstract gesture very much in the manner of Matisse’s 1905 woman in The Green Stripe, and there’s even a pensive Harlequin in her piece The yellow room (2023). Picasso’s portraits of his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter inspired the exhibition title “Teresa’s wings,” as well as Subidé’s From Marie Thérèse (2023)—a painting that depicts a charming figure with a cantilevered armature set against a bruised purple background. The subject’s wide lovely face is half blue and a quarter green with her head quixotically cocked, all balanced on a strong cylindrical neck and haloed by dark sculptural tresses.

Mònica Subidé, The yellow room, 2023. © Mònica Subidé. Photo: Paul Salveson. Courtesy of the artist and Nino Mier Gallery.

Elsewhere, a ghostly sketched-in bowl of oranges holds space for whichever of Cézanne’s you can also imagine or might prefer (I’m partial to the one in the Art Institute of Chicago, but those at The Met and MoMA both have their charms). It scarcely matters which particular bowl of oranges you have in mind; Subidé functions as an art-historical wormhole, an avatar for a way of painting that explores our world by going beyond realism. Subidé’s disarming oil palette of rambling rose, cornflower blue, taffy yellow, felted gray, veined black, a rather imperious lavender, disconcertingly chipper green and fruit-punch red is saturated, but not at all intense. Not quite dusty—though there is an old-soul quality to them that further speaks to their art-historical lineage—but the effect is somehow both ashy and bright.

The works have a surface texture that’s flatter than impasto, but it still speaks to the body mass of oil paint itself, occasionally augmented by elements of collage using her own drawings. This depth of surface amplifies the textural quality as an optical matter, breathing air back into compressed pictorial space. It also opens up a dimension of experiential depth and nuance, giving narrative even in the absence of context, and imparting, if not emotion, at least mood, without drama. That’s what the eyes are for. Despite their schematic nature, whether making contact, pointedly averting their gaze, or simply lost in thought, her paintings are brimming with enough feeling to make each one feel alive.