Your cart is currently empty!

Making Art Concrete

“Making Art Concrete: Works from Argentina and Brazil in the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros” makes for a companion exhibition to the Palm Springs Art Museum’s “Kinesthesia,” also shown under the rubric of the Getty’s PST: LA/LA initiative. It wasn’t intended as such, but the pairing across the Los Angeles Basin was inevitable: the two shows examine postwar abstraction in urban South America and its ties to the European avant-garde, notably to tendencies that derived from the geometric stylization and functional thinking of De Stijl and the Bauhaus.

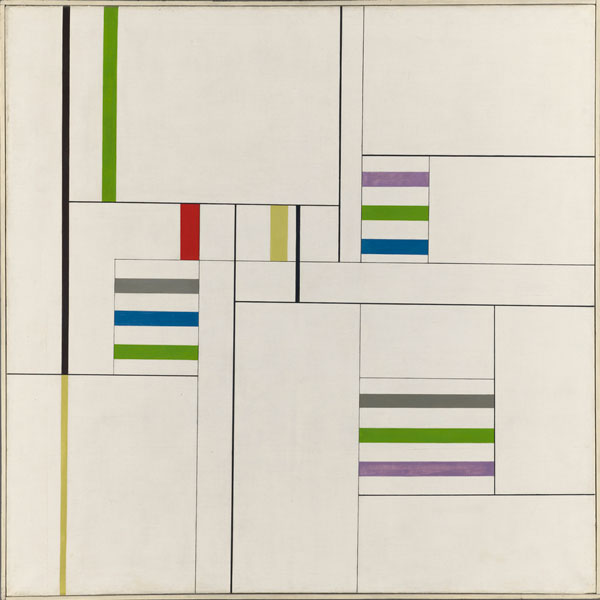

The roots of Concrete Art on the South American east coast go back to the Bauhaus and especially to Paris-based Dutchmen Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg. Doesburg, founder of De Stijl, continued to rally geometric artists around the world until his untimely death in 1931. Several Latin American painters active in Paris came under Doesburg’s sway, and brought their chastened approach to form and image back home.

If the Kinetic Art movement brought the constructivist soul of prewar Europe up to mid-century technological standards, the Concrete Art movement kept constructivism itself alive, finding in it further practical and ideological articulations of color, design and space—including kinetic art, but also op art, shaped painting and minimalism. All these phenomena were internationally celebrated in the 1960s, but, as “Making Art Concrete” demonstrates, they were prefigured by the work of Concretistas as far back as the mid-1940s. (Only one work here postdates 1960.)

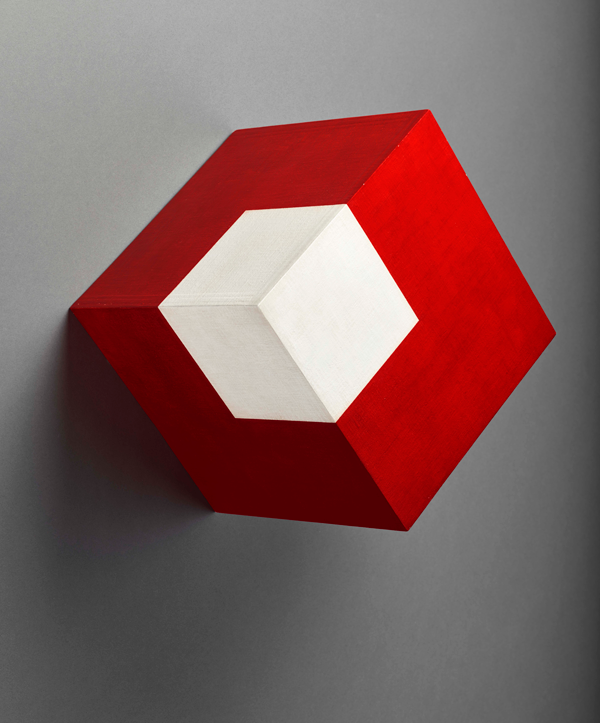

If anything, “Making Art Concrete” is even more geographically circumspect than “Kinesthesia,” limiting itself to work from Argentina (Buenos Aires) and Brazil (Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo). Conversely, while pared down to 16 artists, the Getty show emphasizes collectively derived approaches and ideals (representing six self-declared movement-groups) rather than focusing on the contributions of individuals as “Kinesthesia” does. Still, the show marks the oeuvres of several artists as ripe for renewed and expanded exposure. From Argentina, the shape-shifting paintings of Rhod Rothfuss, Juan Melé, Tomás Maldonado, and Raúl Lozza argue for a geometric painting whose physical edges conform to its pictorial contours, while Alfredo Hlito adapts a De Stijl vertical-horizontal composition to his own rhythmic concepts. Out of Brazil, Lygia Clark, Willys de Castro, Judith Lauand, and Hermelindo Fiaminghi propose an almost architectural reductionism, while the ever-inventive Hélio Oiticica goes them one further with startlingly contemporary monotone panels from the mid-50s.

“Making Art Concrete” was co-organized by the Getty Research Institute and the Getty Conservation Institute, giving the small, proper show its own oblique angles. The GRI had done a show of Concrete Poetry, a distinctly Brazilian invention, earlier this year—avant LA/LA lettre, you might say—and a very few items have carried over. Meanwhile, the GCI has scrutinized the paintings in the show for their materials and methods, finding some very creative techniques on the part of artists who often relied on unconventional and fugitive substances. The visual poetry makes clear formal reference to the painting it accompanies. The conservation documentation is more obtrusive, pulling us time and again into video-stand lectures set right by the objects in question, but is fascinating in and of itself.