Your cart is currently empty!

GETA BRATESCU

Romanian-born, having lived through the tragic absurdities of communism, Geta Bratescu represents the strongest blending of conceptual rigor and narrative impulses. Her wide-ranging oeuvre encompasses drawing, sculpture, video, performance, collage and animated film. In the first room at her Hauser and Wirth exhibition, a Venus-of-Willendorf-like river stone (Woman, 1969) paired with a phallic floor sculpture (Untitled, 2000) emerging from black velvet that one could easily imagine in the grip of Louise Bourgeois, sets the pace for Bratescu’s subjects: body, earth, and the female maker/creator/dramaturge.

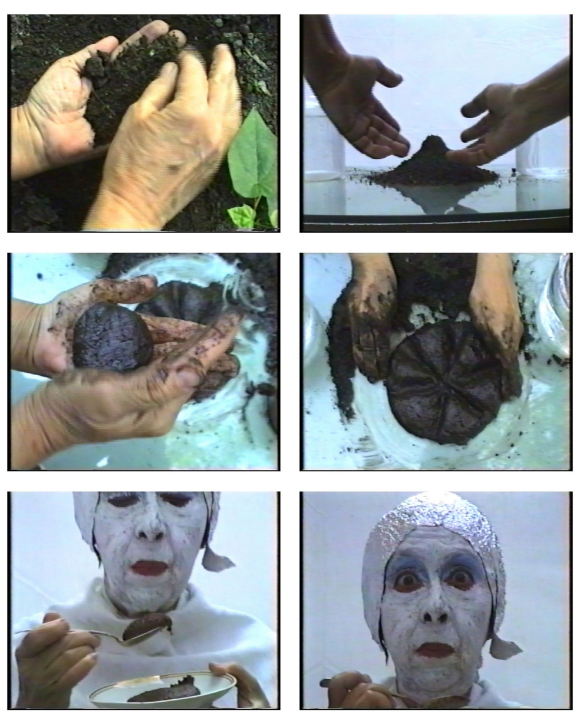

Earthcake (1992), better than any Bruce Nauman video, features the artist, in Kabuki makeup, as she constructs and eats a mud pie. Another black-and-white video whose title translates as “The Hands. For the eye, the hand of my body reconstitutes my portrait” (1977) is a montage of short clips of the artist’s hands moving objects, drawing and smoking. It is shot from the POV of a head-mounted camera likely illustrated in one self-portrait from the photo series Alterity (2002–11)—a thoroughly absurd headgear with antennae of foam, something you’d expect from Mike Kelley. But the sensibility is pure Ionesco, also Romanian by birth: to wit, she’s dressed him up, that existential father figure, by painting a clown nose on a photograph of him (Ionesco—The Clown, 1971).

The liminal outsider figured by the tragic clown becomes star of the exhibition in Bratescu’s 10-minute animated film Aesop’s Walk (1967). In short untitled “fables,” Bratescu sketches one indefatigable character whose long “walk” starts in Roman times (the costumes, the beard) and ends in the Romanian dark ages (night skies, prisons, pits), having circumvented oppressive forces, death and even the grim reaper, sometimes through accident or despite his naiveté. The humor in the work is as outstanding as Bratescu’s charming flat renderings on stark, knockout-color fields. It’s not hard to watch several times in a row.

Aesop’s Walk, with its simplified forms and one particularly animated bouncing ball that leads the narrative forward, queues the primal components of Bratescu’s later collage Poem(2012) and series of series Game of Forms (2010–15). Under the rubric of disarming play, she modulates shapes opposing one another, gathering forces, being encircled (The Lines and the Circle, 2012), flocking, swaying, sharpening. The works’ jocular nature is an afterimage of a youth spent under the thumb of censorship, where mute forms could be coded as stories, morals, lessons in resistance—her lightheartedness, probably considered a damnable offense in some company.

Though Magnets in the City (1974), her proposal to install massive magnets in New York parks to remind people of forces working against them, is maybe too polite (why not disrupt the traffic by pulling car bumpers off too?), it demonstrates that the artist sees her subjects—us—with great sympathy.

Go with your wits about you to Geta Batescu’s The Leaps of Aesop but prepare to be disarmed by this nonagenarian’s extensive explorations. Like flies drawn to the eyes of an admirably old mare, we find only a moment to ruminate on each accomplishment before she blinks us away.