That Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg are both having retrospective exhibitions in California concurrently, at The Broad in Los Angeles and San Francisco MOMA respectively, is undoubtedly coincidental, yet the timing seems just right. Both artists were part of a watershed in contemporary art, beginning in the late 1950s, that has influenced how we see art currently. That transition from Abstract Expressionism’s dominance to the myriad experimental activities of the 1960s and ’70s was one of the most significant in the last 50 years, and its effects continue to be felt. Johns and Rauschenberg’s emergence and influence in the early 1960s had much to do with that shift.

Rauschenberg’s earliest works exhibited in SFMOMA’s “Erasing the Rules” reflect the purity and autonomy of Abstract Expressionism. In particular, his “Black Paintings”—monochromes of enamel on newspaper collage—have much in common with the late work of both Mark Rothko and Ad Reinhardt, and have recently been referenced in relation to Pollock’s “Black Paintings” from the very same years (1951–52). But immediately following these quite insular and austere works, Rauschenberg explodes. His joyous “Red Paintings” mark the beginning of his most compelling and experimental period, the Combines. The earliest of these succeed as the seemingly unlikely fusion of Abstract Expressionist painting techniques with objects from the real world and still stand as the crowning achievement in his oeuvre. The almost manic sense of exhilaration expressed in the mash-up—fans used to blow air currents across a work’s surface, tires, coke bottles, taxidermy, a bed, or any of the innumerable curiosities Rauschenberg absorbed into the Combines—amazingly retains much of its punch, even after so many years and so much reproduction in art history texts. As bold and experimental as the Combines have remained, Rauschenberg’s later works never attained the radicalness achieved in this break-out period.

The same might be said regarding the work of Jasper Johns, who has often been paired with Rauschenberg in art history; the two were lovers and partners during this early period, advising and influencing each other. Johns’ early works, like Rauschenberg’s Combines, engage with the vocabulary of AbEx painting. Beginning with Flag (1954-55), the seminal work in “Something Resembling Truth” at The Broad, Johns’ flags, targets and maps are all paintings of things that are inherently flat, rectangular, and often hang on the wall like a painting. Yet they are depictions of things that resemble a painting, but are not. Johns’ paintings of them confound the distinction between the actual object and its representation.

It is interesting now, over 60 years later, to compare two key works by each artist from the critical year of 1955—Johns’ first Flag, and Rauschenberg’s Bed. Each work represents a decisive moment. Johns’ work was famously suggested by a dream he had of painting a large American flag, which he simply actualized when he created the painting. Bed was prompted by necessity—Rauschenberg literally had nothing to paint on, so he used his quilt. Each account is well known through statements and interviews with the artists, and both are intriguing in that the initial motivation was something outside of the artists’ control, and almost arbitrary. But both Johns’ painting of the flag and Rauschenberg’s seeing the bed as a painting opened up a compendium of possibilities.

Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram (1955–59) ©Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

The fact that both Johns and Rauschenberg made their most memorable and influential work at the outset of their careers should in no way suggest that their artwork has not been strong for the duration.

Both exhibitions are testaments to the powerful work each produced over subsequent decades. Rauschenberg’s use of first, silkscreen, and later, ink jet printing to incorporate photography into painting was innovative and groundbreaking when he did it, in both mediums.

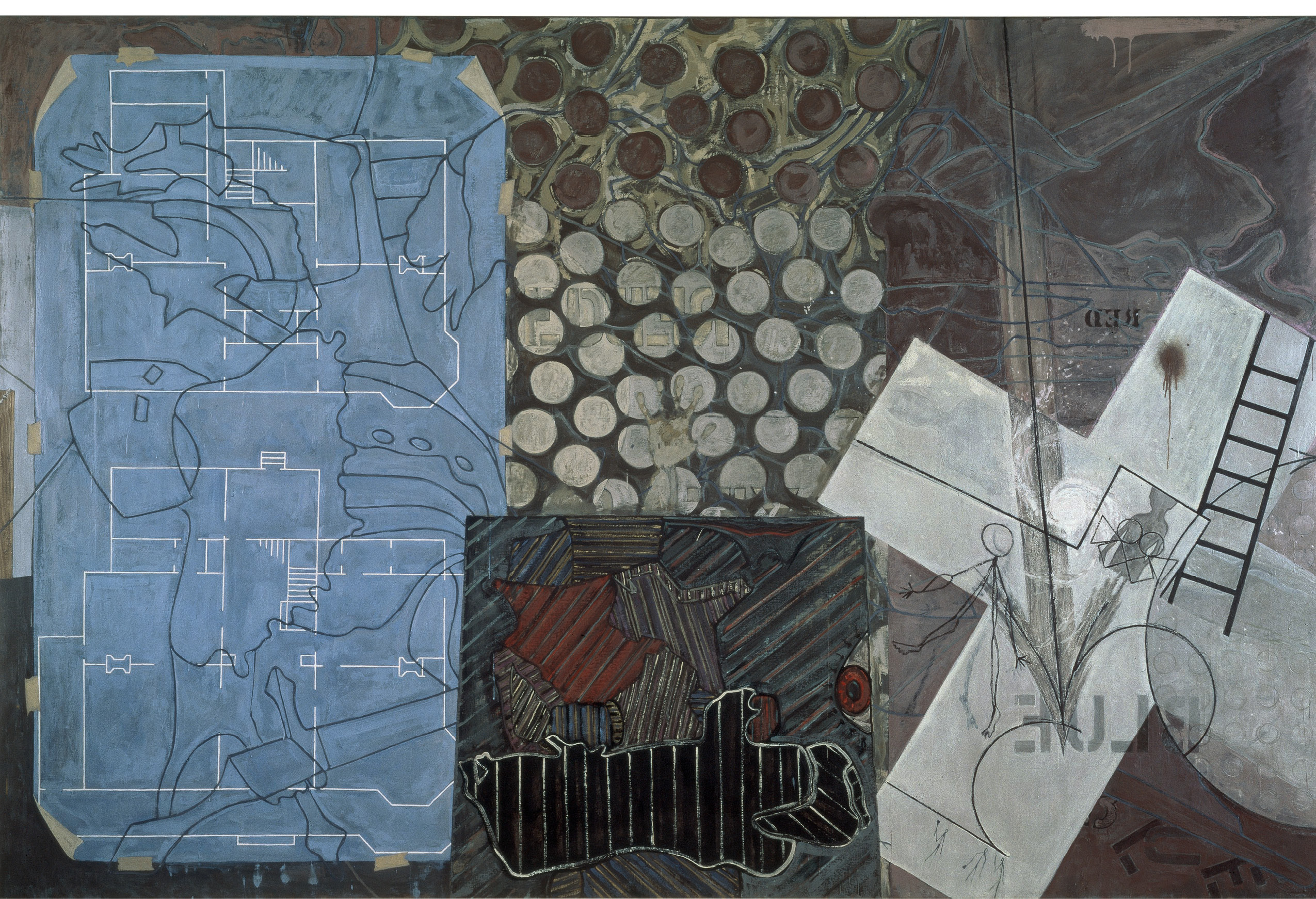

Johns’ retrospective, which was designed thematically rather than chronologically, shows the depth and variety of forms his work has taken since that initial period following the Flag painting. The exhibition makes one want to return for multiple viewings, since his work is subtle and mysterious, and reveals itself slowly. There is much to admire in his continued dialog with abstract painting, which crops up repeatedly, most obviously in the crosshatch patterning that began with Corpse and Mirror (1976). Johns recently stated in an interview that one reason he decided to do the exhibition was that he wanted young people to see his work. And they would do well to. The exhibits reveal Rauschenberg and Johns’ fundamental impact on the course of contemporary art.

0 Comments