Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Carrie Paterson

-

Man on the Moon

The Moon landing’s 50th anniversary can’t be avoided. Waxing at full, it feels like the last gasp. The defining moment for some in the baby boom generation, what does the Apollo 11 landing obscure?

The moon shadow cast by one artist’s timely work points the way. Richard Clar, an environmental artist based in Northern California and Paris who works exclusively in the environment of space, has brought the mission full circle. Two works, one laser-based and one radio-based, were both transmitted from observatories in Europe this July at the exact 50-year anniversary of Neil Armstrong setting foot on the moon. They rehearse and recall Armstrong’s trepidatious excitement, as well as a legacy of contemporaneous sculpture and Land Art that used lines in space, walking, distance, and the absent human figure. The era was one of extraordinary social change complemented by the growing transformative power of media.

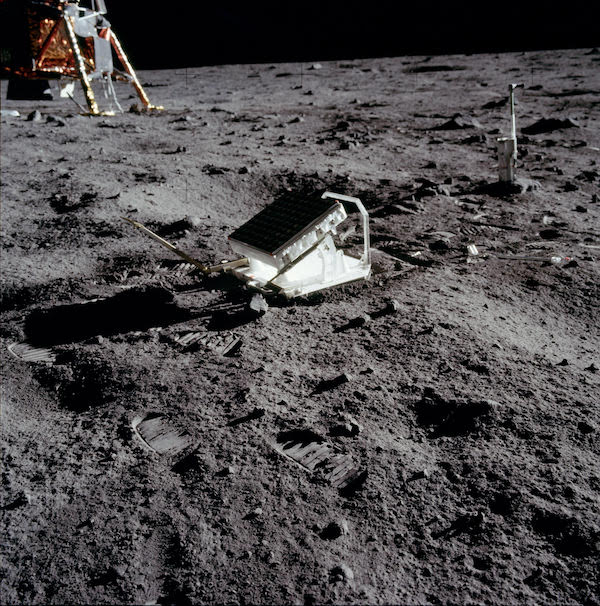

Apollo 11 Retroreflector. Photo credit: NASA. Clar’s July 21 works are both titled Giant Step. One was a laser transmission sent from the Côte d’Azur Observatory high above the French Riviera at local time 04:56:15 to the exact GPS location where Armstrong’s faded footprint remains undisturbed today. A small retroreflector panel placed there by Armstrong and Aldrin has been used continuously since 1969 for lunar surface laser-ranging, which is used to measure the distance the Moon is receding from the Earth each year, and for substantiating Einstein’s theory of relativity. At the speed of light, Armstrong’s famous statement “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” was beamed back to the same historic spot using Morse code.

Originally developed in the early-19th century, Morse code was the gold standard for maritime distress messages and serves as the link between the lost and troubled seafaring vessel and Clar’s line of light in space. Calling back to Armstrong’s shadow footprint, it reframes the “giant leap” and opens up Armstrong’s quote for reinterpretation. Clar’s is not a leap, it’s just a step, one in a chain. We walk — for pleasure, for protest, toward each other or away. But we have walked in chains, on death marches, and toward the execution chamber too: (Dead Man Walking, dir. Tim Robbins, 1995). Still, Clar reminds us, a few men (no women) have walked on the moon, and those traces of us will remain for eons. In light of everything human, this simple fact seems just cause for celebration.

Telescope projecting laser beam towards the moon at the Cote d’Azur Laser Ranging Station (MeO), Calern Observatory, Plateau de Calern, Grasse, France, 21 July 2019. Photo by Rebecca Marshall. But 50 years is a tiny amount of time in planetary geology, less than an expected error in measurement, such that an observer from another point in time and space might get the sense the landing and the circular utterance had occurred nearly simultaneously. Yet the circularity of reference in the line of transmission creates the roundness and fullness of Clar’s simple but powerfully ephemeral and dematerialized work.

For a moment, let’s consider a few dissimilar contemporaneous visualizations of man’s “Steps”; the first example, the Civil Rights Era Selma to Montgomery protest marches (1965). Second, Richard Long‘s A Line Made By Walking (1967) wherein, trampling the grass in a straight path through an open field with no witnesses, Long referenced prosaic human capacities, and at the same time human frailties and eventual disappearance, recording his traces over the landscape in an iconic black and white photograph now seen as an early progenitor of Land Art. Third: Marvin the Martian and Daffy Duck compete to claim a new planet for Mars or for Earth (Looney Tunes, circa 1969–1970), casually blowing each other up all the while. And fourth: the American Indian Movement (A.I.M.), advocating for rights and sovereignty, leads The Longest Walk, an awareness-raising, spiritual march in 1978 across the country to Washington D.C. (revisited in 2008) to bring attention to anti-Indian legislation.

L to R: Dr. Clément Courde, Alexander Minangoy, Dr. Jean-Marie Torre, Richard Clar, Thierry Hocquaux and Rebecca Marshall, Cote d’Azur Laser Ranging Station (MeO). Calem Observatory, Plateau de Calem, Grasse, France, July 21, 2019. Photo by Rebecca Marshall. Clar remembers watching the Moon landing live on TV. He reflects:

Perhaps no other event in human history was seen in real-time by so many people around the world … something I will never forget. At the time, I was not thinking in terms of us, or anyone else, becoming a space-faring nation. My focus was on the present; what was happening right before my eyes. Seeing that first footstep on the moon was somewhat of a mystery. It represented something that was going to happen, but it was not exactly clear what that was.

Yet,

Around one week after the moon landing, I was visiting the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico. I struck up a conversation with a group of Native Americans and asked what they thought about our landing on the moon. The unanimous response was that they were not happy at all for they regarded the moon as a sacred space that we somehow violated. So for them, Giant Step has a different meaning.

The history of exploration and conquering, as well as the troubling nature of these Western pastimes, are reflected in the enthusiasm among scientists who wanted to perform and facilitate Clar’s stunt with him. Any artist working in the public sphere needs buy-in, and the message was clearly positive to those on the transmitting end. Difficult to aim a laser at a moon target and hit it at a precise time? Yeah — game on! But what did we accomplish going to the moon? It was a huge leap for industry, and still is a political football that gets thrown around, sometimes by feckless quarterbacks such as our current president, who are trying to leave their own distinctive mark in history: Space Force!

Space artist Richard Clar observes technical preparations for the transmission of his laser message to the moon, part of his artwork Giant Step, at the Cote d’Azur Laser Ranging Station (MeO), Calern Observatory, Plateau de Calern, Grasse, France, 21 July 2019. Photo by Rebecca Marshall. We will soon walk on Mars. Meanwhile, the 50-year-anniversary Moon landing celebrations are unfettered spectacle. They present a particular kind of teaching opportunity, but few take it. That is where Richard Clar‘s second work of July 21, 2019, comes in.

Part dirge, part commemorative memorial, the other part of Giant Step (begun in 2015) uses an EKG of Neil Armstrong‘s heartbeat from NASA’s Apollo archives sonified first into a single tone by Dr. Ryan Compton, then into a heartbeat sound, as the baseline for a remarkable piece of music improvised by LA-based jazz double-bassist Roberto Miranda which is set to video from the moon’s surface of that day. Performed as a “Moonbounce” from the observatory in Dwingeloo, Netherlands — where radio engineer Jan van Muijlwijk and media artist Daniela di Paulis pioneered the technology in 2009 — the moon is used as a huge radio reflector for an Earth-Moon-Earth transmission.

Armstrong’s footprint image after being bounced off the moon. Received by an 25m Astropeiler antenna in Stockert, Germany.

Armstrong’s footprint image after being bounced off the moon. Received by an 25m Astropeiler antenna in Stockert, Germany. Armstrong’s biometric information, unheard by the public until Clar’s work, provides the insight we need to understand this moment. These are human beings just like us who are being sent out on the most dangerous missions. Like soldiers in war, they are willing to make the greatest sacrifice. While we buy freeze dried ice cream, watch IMAX movies, and proceed in capitalist nostalgic frenzy to the gift shop, we would do well to remember the haptic, the fragile, and the connection to each other. Isamu Noguchi, who also dreamed of doing an artwork on the Moon, has famously said: “If sculpture is the rock, it is also the space between rocks and between the rock and a man, and the communication and contemplation between.”

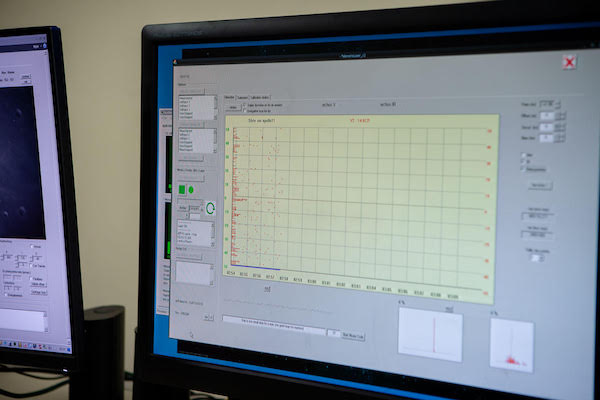

Data screen showing live feed from the laser during the transmission of space artist Richard Clar’s laser message to the moon, part of his artwork Giant Step, Cote d’Azur Laser Ranging Station (MeO), Calern Observatory, Plateau de Calern, Grasse, France, 21 July 2019. Photo by Rebecca Marshall. In our interview, Clar continued to reflect:

I also saw Sputnik 1, launched October 4, 1957. I stood in the backyard of our Hollywood home with my parents as we watched the Russian satellite move across the night sky. It seemed a little ominous at the time, as most people, myself included, had no idea of what it meant. For many in my generation, who grew up during WWII, we were aware that Japan was sending incendiary balloons capable of reaching the US. My parents talked about this and I was afraid. Even as a five-year-old, I was frightened by this idea of balloons starting fires in the US. This created a mindset to be aware of the unknown, or out-of-the-ordinary objects that moved across our skies.

Artist Richard Clar. Photo by Dom Garcia When Long created his Line, he thought of it as not-art, and an insistence upon being alive. And there was no one watching live on TV. Or Facebook. In a December 2018 article in Wired, Jeff Bezos described his Promethean Blue Origin mission to build space highways inspiring many generations to come: “I hope to create a thousand Mark Zuckerbergs,” he said. If this doesn’t make you pause, as I’m sure it would Armstrong, who was famously mute after his earth-shattering step, well, go back to your social media. In the end, our space-faring dreams are large and speculative, but the reality is certain. Isamu Noguchi brings the absurdity home: “Ultimately, I like to think that when you get to the furthest point of technology, when you get to outer space, what do you find to bring back? Rocks!”

-

REICH RICHTER PÄRT

Joy, transformation, transcendence—all lofty goals of early abstract expressionism—are exalted in the present tense at The Shed in the world premiere collaboration of three major 20th-century artists, now in their sunset years.

This stellar exhibition is marked by the long history of painted depictions of the divine and at the same time informed by flash mobs, minimalism, Eastern Orthodox Christianity, the brutal modern history of Eastern Europe, and not least, Gerhard Richter’s signature experimentation in layering and tooling paint. Haunting musical works by Steve Reich and Arvo Pärt—revolutionary composers known to set spines tingling—and the patient talent of filmmaker Corinna Belz (dir. Gerhard Richter Painting, 2012), who translates the artist’s methods into the video medium, complete this participatory hybrid techno-performance, which deprives the observer’s position of neutrality.

The collaboration takes place over 60 minutes in two rooms: a vestibule gallery featuring a tear-jerking and haunting “alleluia” song cycle by Pärt (Drei Hirtenkinder aus Fátima [Three Little Shepherds of Fátima], 2014) that erupts a cappella from singers scattered among the unwitting audience, and a second, larger gallery with Richter and Belz’ immersive floor-to-ceiling video accompanied by a live orchestra playing a world premiere by Reich, written specifically for Richter’s video—but based on Richter having listened to Reich’s structural experimentation over decades to inform his painting.

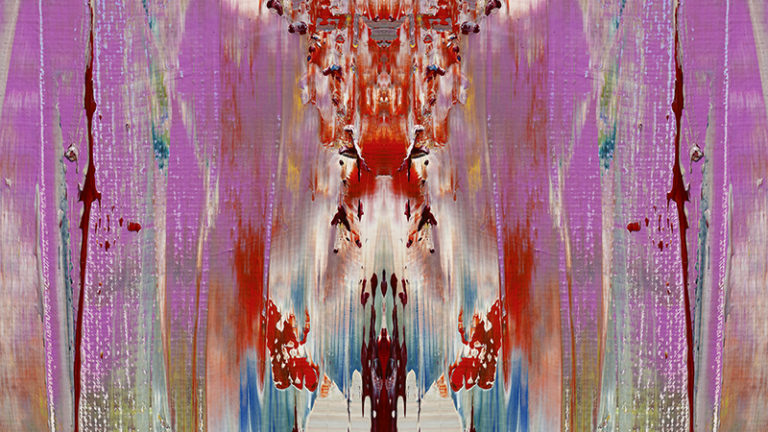

©Gerhard Richter (2019), courtesy The Shed. While the viewer’s experience is linear, in its totality Reich Richter Pärt is a cycle, repeating hour after hour, day after day, for two straight months (alternating performers from Ensemble Signal, the International Contemporary Ensemble, the Choir of Trinity Wall Street, and the Brooklyn Youth Chorus). This linear/circular dichotomy is the epicenter of the work and entwines the audience within an existential contradiction endemic to the human life cycle, which we experience both as creators and observers to phenomena of beauty.

In the first gallery, Richter’s columnar digital prints, inspired by his algorithmic work/book Patterns (2012), applied to the 15-foot-high walls as architectural elements, reference Richter’s fascination with stained glass. The metaphor of a house of worship extends to large, wall-hung tapestries based, like the video in the next room, on his 2016 abstract painting 946-3. Made through the algorithmic splitting, doubling and folding of segments of Richter’s paintings, these patterns are like Rorschach tests or marble, once moving, now static objects of contemplation.

Yet they are unsettling. Rothko’s Chapel (completed after the artist’s suicide in 1970) comes to mind as an after-affect of the exhibition, when the Richter/Belz video of the second gallery has played out. Seemingly an apex to Richter’s production, it provides a way to conceptualize his life’s work in light of his advancing age but without his hand or presence. Multitudinous “color bars” bracket the Richter/Belz video, and as the painting’s abstract color imagery is woven and animated through cutting and layering, its mesmerizing, vibrational energy communicates spiritual yearning while Reich’s accompanying ode-to-joy memorializes Richter, as if postmortem. The climactic resolution of the video’s ornate patterning back into strata of color recalls a speed Paul Virilio might refer to as the logical perception of war, but also suggests the artist foreseeing his own endurance after death. We recall Belz’ interview when Richter reveals he never again saw his parents after leaving East Germany to become an artist, his past like a shadow in the many paintings and images he has destroyed on this path to envision a joyful, transcendent future—bringing his audience to awareness: this awaits us all.

-

Inheritance

Three immersive films from Africa about political and cultural resistance use tropes of the Imaginary from Fanon to Lacan to challenge inherited postcolonial mindsets.

Kudzanai Chiurai presents a gorgeous, disorienting series of seven tableaux dramatizing the agony of Zimbabwe as a young nation. Colonial capitalism, as much as religious fervor and sectarian violence play throughout the intensely stylized scenes. With a mesmerizing soundtrack directed by João Orecchia, We Live in Silence (2017) proceeds at perhaps five frames-per-second so that we linger on every eye-blink, laugh or bodily twist. With men given perfunctory roles in violent scenes as members of the Army, priesthood, militia or victims, the innate objectification of the camera on the female lead clearly collapses woman/nationhood, seemingly uncritically, especially regarding the display of her body. A nod to the important presence of women in the guerrilla movements of the early 1980s could partly salvage this reading (cf. the film Flame—1996, Ingrid Sinclair), but the final banquet, where (male) bodies are shot and beaten brings home the point: the national imaginary, theatricalized by the artist, is a national emergency.

Kudzanai Chiurai, We Live in Silence, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery. Mikhael Subotzky’s 3-channel installation WYE (2016), viewed from reclining beach chairs on a floor of sand, lulls us with the sound of ocean waves into considering how a techno-surveillance state commands the Imaginary to meet the accords of post-apartheid society. Set in a past-present-future somewhere on the coast near Johannesburg, rotating films show an early European explorer’s treasure uncovered by a present-day Caucasian lighthouse keeper with the help of a scantily paid black laborer. We learn of the keeper’s future embodiment as a kind of Black Mirror-like virtual teaching aid after he willingly (?) submits to the “Body Emancipation Project,” which renders his confessional email exchange with a friend visible in all key strokes: but the fear of black faces in Jo-burg (“a powder keg”) is deleted; the “incident” that happened to a mutual friend—deleted, yet the black man who assisted him still “came out of nowhere,” leaving the suggestion that Africa will again be a place to dream about occupying, without bodies, as it was before history’s repercussions.

The strongest piece in the show is by filmmaker Zina Saro-Wiwa, daughter of author/activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, who actuates a “Decolonizing the Mind” by inviting viewers to share a meal with a chorus of faces in the Niger Delta. A dozen screens set upon individual tables display the visceral chewing of local dishes from start to finish. Like Instagram photos from eager foodies, high establishing shots of each plate cut to a person eating pumpkin leaf soup, roasted snails, pounded sweet potatoes or yard apples with spicy nut butter. The stoic expressions of finger-sucking locals (no utensils) resist becoming “spectacle” because Table Manners (2014–ongoing) is interrogating the viewer. Shell Oil production and global consumption has polluted Ogoniland, sickened people, and bred decades of violence (including Saro-Wiwa’s father’s execution). The tables are turned, and through the indelible, inscrutable images of the Ogoni faces before us engaged in a simple act of eating, we see their resolve to remain on a land shadowed by bloodshed in order to imagine its future.

-

Lauren Satlowski

Lauren Satlowski’s four new paintings at Odd Ark situate us squarely in our anxious feminist moment. Their landscapes are creepy, with tinges of the natural; their delicious surfaces bounce the gaze around like the mise en scène for Spielberg’s child-android in A.I. and their colors flare like a Kubrickian operatic interlude.

Each work features a female caricature, humorous and strange, distinctly out of place yet a fitting “object” in her element. In Feather Bowling (all works 2018), the first of three 40” x 30” panels, a Venus of Willendorf/astronaut figure emerges from a dark primordial slime. A golden light kisses her body’s surface, like the afterglow of a neon sign that makes puddles green at night. The amount of refractive surfaces and colors are slippery for the eye, and in looking for meaning one falls into pits or fissures of light. A holographic cartoon of a woman’s face floats on the object’s surface. On the figure’s arm we can barely register the reflection of… is it the painter? Or is Satlowski rendering painting itself as a character?

In Seagull, a vacant doll perches on a rock as the Western or Martian sun sets on an infinite landscape we cannot see. The doll’s frozen face is engulfed like an Arctic explorer in a puffy pewter-colored hood, dead to light and decorated with nineteenth-century floral flourishes. Her Amelia Earhart red aviator-scarf shimmers triumphantly out of focus, and her Captain Hook appendage is shocking. We stare but are non-essential. She is the survivor.

The helmet flowers from Seagull are reprised as a conjoined twin figure on a single stem in 91.5 Los Angeles, a nod to the USC classical music radio station. The neon yellow flowers are more evocatively figural than the black costumed woman with pendulous breasts onto whose hand the flowers weep glowing fragments. Satlowski handles this light, and specifically its autonomy, in a way that marvels at paint’s ability to be more than the light it reflects. It is somehow essential yet mutable; we project meaning there, but its materiality escapes.

Satlowski’s figures, in these paintings as well as in her gouache on paper paintings in the back room, appear as ciphers in a fluid medium. Each painting refutes a simple answer about identity and fixability by emphasizing the hypnotic element of paint and its psychedelic, transmutable potential. In several of the gouache on paper works—pages from a future or past book—this relationship to light is amplified by a naked and hunched female cartoon who fishes with her hands through eddies of rainbows. The moment of apprehension is elusive and maybe psychotic, as in the smaller painting Just Because You’re Paranoid Doesn’t Mean They’re Not All Out to Get You, when an examination of Satlowski’s “Id” character “Robber Girl,” who carries a cartoon sack over her shoulder, reveals it’s painted on a thin white veil covering an image to haunt law-and-order types, The Joker.

This is Satlowski’s humor and her critical strength. She’s playing around, but the game is serious and has implications for both painterly and contemporary political issues.

-

Tomás Saraceno

Two short films in “Solar Rhythms” at Tanya Bonakdar open Tomás Saraceno‘s proposal for thermodynamic collaboration and remaking human relationships to the Earth.

The first, taken during Saraceno’s ambitious, record-setting flight in White Sands, New Mexico with his D-O AEC Aerocene sculpture/balloon (2015), has the home-movie quality of a Robert Smithson film. Saraceno joins forces of sun and wind as romantically as Smithson did earth and water, to achieve the first pure solar flight.

But Saraceno is an artist-scientist whose innovations extend from aeronautics to arachnology. If it wasn’t clear already from his Hanging Gardens–Cloud Cities (guest artist, Artillery 2011), which have lofted participants on transparent cushions at major museums, then the threads in his films (hot air balloon tethers) and his Calder Upside Down mobiles (2017), ballasted with a hemp rope and stone, draw us closer to the spider’s world, the complicated geometry of its webs (seen in the complicated hand-tied Zonal Harmonic, 2017), but also its employ of nanotechnology to escape gravity.

Tomás Saraceno, Aeolus (2018), courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York. In another darkened room, three skeins of woven spider silks about eight-feet long undulate to tones played over a loudspeaker in Sounding the Air, an ongoing project. Harvested from spiders in Saraceno‘s safekeeping (with three full-time assistants and ample food) the webs present a philosophical conundrum about human innovation. Future space elevators made of similar proteins could extend our living capacities into the stratosphere and beyond. But social stratification, Saraceno’s work suggests—despite its starry-eyed idealism—weighs us down. His solution? Open-source his discoveries, which include spider web analysis and 3D modeling, home balloon kits (Aerocene Explorer, 2015–) and an app (Aerocene Float Predictor, 2015–) that simultaneously tracks suitable air currents for ballooning and, by extension, global warming. Also: challenge FAA regulations and reclaim the desert, where technocrats, power companies, and power brokers aim to make solar factories and launch pads for our collective survival.

Saraceno’s second film, Diving into the Ocean of Air (2017), documents Aerocene Explorers flying over a contested lithium extraction site. The film reminds us why our devolving social structures in the “enlightened” information age still prevent us taking to the air in this utopian way. Over Salinas Grandes salt lake in Saraceno’s native Argentina, his Aerocene sculptures are looming kites visually reflecting the human misdeeds and terrors that have occurred in the stretches of desert below, specifically in neighboring Chile during Pinochet’s junta. In the mind’s eye, reflecting on the black balloons as if they are film screens, we imagine the thousands of people disappeared with no trace, the desert a black site of the most extreme degree. Lest we forget, hot air balloons were first used in French-Anglo warfare [see: Falling Upward: How We Took to the Air by Richard Holmes]. As Saraceno’s abstract forms quietly steal over the desert like military drones, they gaze down (as do the film’s cameras) instead of floating away from the troubled planet. But then, using no power except the sun, when nighttime comes these balloons of hope, or despair, will fall. The Earth remains our tether, our heads in the sand.

-

GETA BRATESCU

Romanian-born, having lived through the tragic absurdities of communism, Geta Bratescu represents the strongest blending of conceptual rigor and narrative impulses. Her wide-ranging oeuvre encompasses drawing, sculpture, video, performance, collage and animated film. In the first room at her Hauser and Wirth exhibition, a Venus-of-Willendorf-like river stone (Woman, 1969) paired with a phallic floor sculpture (Untitled, 2000) emerging from black velvet that one could easily imagine in the grip of Louise Bourgeois, sets the pace for Bratescu’s subjects: body, earth, and the female maker/creator/dramaturge.

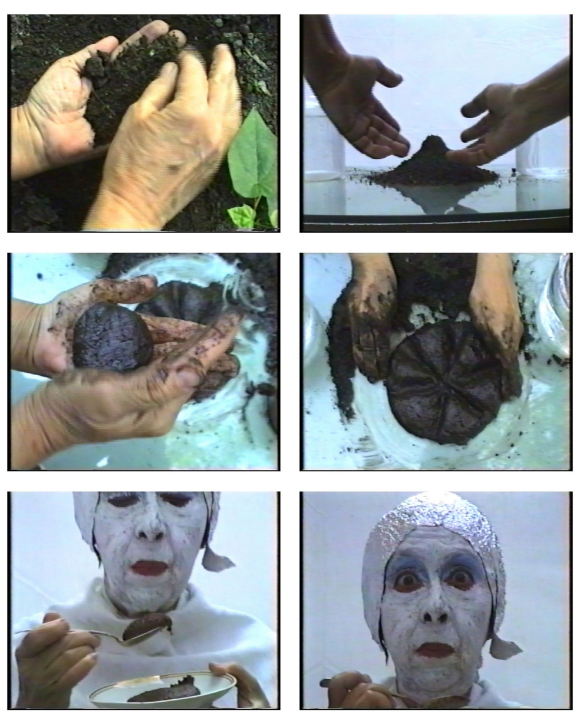

Earthcake (1992), better than any Bruce Nauman video, features the artist, in Kabuki makeup, as she constructs and eats a mud pie. Another black-and-white video whose title translates as “The Hands. For the eye, the hand of my body reconstitutes my portrait” (1977) is a montage of short clips of the artist’s hands moving objects, drawing and smoking. It is shot from the POV of a head-mounted camera likely illustrated in one self-portrait from the photo series Alterity (2002–11)—a thoroughly absurd headgear with antennae of foam, something you’d expect from Mike Kelley. But the sensibility is pure Ionesco, also Romanian by birth: to wit, she’s dressed him up, that existential father figure, by painting a clown nose on a photograph of him (Ionesco—The Clown, 1971).

Geta Bratescu, Earthcake (1992), photo by Timothy Doyon, ©Geta Bratescu, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. The liminal outsider figured by the tragic clown becomes star of the exhibition in Bratescu’s 10-minute animated film Aesop’s Walk (1967). In short untitled “fables,” Bratescu sketches one indefatigable character whose long “walk” starts in Roman times (the costumes, the beard) and ends in the Romanian dark ages (night skies, prisons, pits), having circumvented oppressive forces, death and even the grim reaper, sometimes through accident or despite his naiveté. The humor in the work is as outstanding as Bratescu’s charming flat renderings on stark, knockout-color fields. It’s not hard to watch several times in a row.

Aesop’s Walk, with its simplified forms and one particularly animated bouncing ball that leads the narrative forward, queues the primal components of Bratescu’s later collage Poem(2012) and series of series Game of Forms (2010–15). Under the rubric of disarming play, she modulates shapes opposing one another, gathering forces, being encircled (The Lines and the Circle, 2012), flocking, swaying, sharpening. The works’ jocular nature is an afterimage of a youth spent under the thumb of censorship, where mute forms could be coded as stories, morals, lessons in resistance—her lightheartedness, probably considered a damnable offense in some company.

Though Magnets in the City (1974), her proposal to install massive magnets in New York parks to remind people of forces working against them, is maybe too polite (why not disrupt the traffic by pulling car bumpers off too?), it demonstrates that the artist sees her subjects—us—with great sympathy.

Go with your wits about you to Geta Batescu’s The Leaps of Aesop but prepare to be disarmed by this nonagenarian’s extensive explorations. Like flies drawn to the eyes of an admirably old mare, we find only a moment to ruminate on each accomplishment before she blinks us away. -

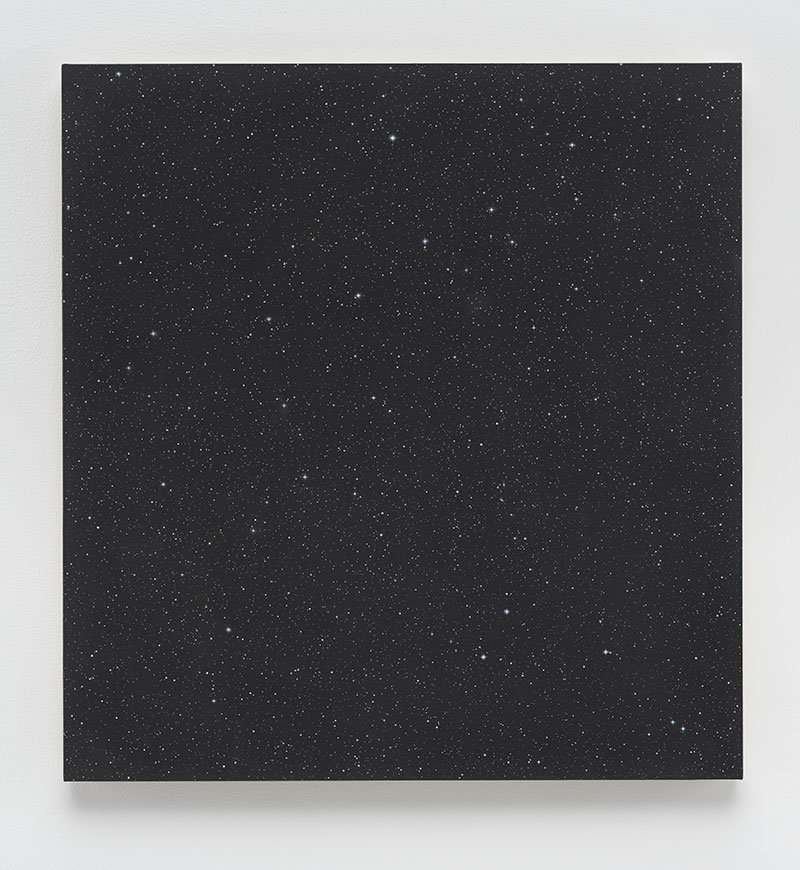

VIJA CELMINS

Vija Celmins’ work is best when you are caught by surprise—don’t read the manifest, just board the ship. Sublime encounters open quiet pathways to deep consideration of the now-octagenarian artist, her times and her legacy.

Celmins’ exhibition at Matthew Marks Gallery is steeped in matters of gravity in 40 years of her later works. Notably absent is her brief fascination with the age of televised war. Frank Sirmans’ writing (Vija Celmins: Television and Disaster, 1964–1966 [Yale, 2011]) should be called upon just for background—white noise—if only to remind us how Celmins has long considered art’s ability to fix death’s image.

Born in 1938 in Riga, Latvia, Celmins’ life has been circumscribed by war. Occupied by the Soviet Union until 1991, Latvia was an eastern outpost of the Nazi concentration camp system, a site of horrific executions by Einsatzgruppen death squads who left tens of thousands of Jews, Communists, and other “undesireables” in mass graves, yet the mention of Jews killed was forbidden by Soviet authorities. How can Celmins’ work be read against “suppression”? Many won’t know that Celmins was invited to create a work for the Hall of Witness at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; though not ultimately selected, her work, like that of Christian Boltanski, has a relationship to Holocaust memorials and, I posit, Riga’s adjacent Bikerniecki Forest, where a constellation of broken pillars memorialize the disappeared.

Vija Celmins, Two Stones, (1977/2014-16), © Vija Celmins, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. Celmins’ large canvases picture layers of deep space. Using thinly gesso-embedded stars, she pushes the comfort of a flat “readable” surface. These Hubble-like “windows” as in Night Sky #24 (2016), present galaxies so old they may be gone entirely. But our relationship to time obscures this from us. What do we learn from the errant paint-glop/star that wanders around the edge of the canvas? Looking at Celmins’ magnificent Blackboard Tableau (2007–15) installations of twinned chalkboards—one found and one fabricated—we find other indexical, extra-dimensional details like the gum of duct tape removed, copper nails buried with past force, scratches that mars the finish. The human hand wrote its sign, and it betrayed its violence. Lingering at the edge of the boards is the chalk’s ashen semi-solid state, somewhere between permanence and trace, memory and matter, the sign and its disappearance. “Little object a.”

The rhyme between the paintings and the blank slate of the tableau questions the impulse of energy required to start the language/universe over again. What would be different? What would be copied? What is inevitable?

The standout of the show is Two Stones (1977/2014–16), each palm-size and of a mass comfortable for a paperweight and place roughly 90 degrees to each other, where two hands seemingly just set them. The “real” pinkish granite echoes the stars with its white and black flecks, while the other, its twin made of bronze and painted, suggests only weight is the difference. But it’s impossible to know which is the mirror. It’s not just an inside joke or reprise of art’s nature/culture theme. The stones ask about the nature of time in reference to human flesh and ambitions, and suggest how possible it is to free energy with the sound of the two being struck together. Which will survive? The stone, or the artist’s great clap in an otherwise astonishingly silent oeuvre?

-

Turning Art Upside Down

Prestidigitator, composer, engineer and conceptual artist Nahum hails from Mexico City, has lived in London for many years after a degree from Goldsmith’s College, but really, he belongs anywhere. Recently he and eight other Mexican artists, along with a Mexican scientist, spent a day floating above our planet in zero gravity on a parabolic flight. Russians flying the huge Ilyushin 76 MDK aircraft lifted them into the stratosphere in order for them to make an astounding number of conceptual artworks in the span of a few hours. The Russians had never seen anything like it. These weren’t the first artists on their plane, but the first Mexicans, yes, which has brought to Space Art a welcome new perspective.

Ale de la Puente, An Infinity without Destiny, 2015. On board: 50 cameras, a core sample from the north of Mexico, a large hourglass with Mexican sand, and—among other props says Nahum—“a piñata shaped like a star filled with Mexican candies and confetti.” The artists did not get to smash it however, as the forces of such impacts in zero gravity are violent, and it actually would be quite dangerous. So, a Russian commander “exploded” the star, and the glitter, confetti and candies, like a Felix Gonzalez-Torres piece in Heaven, floated free throughout the cabin. Nahum says the Russians loved them, but were less thrilled with the detritus they spent weeks cleaning out of their plane.

Some artists on the flight made two to three pieces. All are in a traveling exhibition currently on view at the Laboratorio Arte Alameda, an arts complex associated with the Museo de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. “La Gravedad de los Asuntos (Matters of Gravity)” will travel from Mexico to Moscow at the end of March; then to Slovenia in July; to El Paso, Texas in November; and will finish the tour in São Paolo in March 2016.

Nahum preparing for the zero gravity flight. Photo: Space Affairs. Artillery: Nahum, what did you want to achieve with this zero gravity flight in terms of art?

Nahum: The intentions of the project were to explore gravity, this universal force on the planet that has shaped us, and everything we know here, by changing our perspective on it through its absence.

Can you give some examples of the works in the show?

One artist, Armas, took a core sample [from the north of Mexico where she’s from] into the plane and freed the earth layers from thousands of years of history. Ale de la Puente explored time and gravity using a huge hourglass with sand. In zero gravity, time wasn’t flowing as it does normally here; it flows all over the place. She was reflecting on the links between time, space, and gravity because gravity shapes space-time.So ideas like speed are displaced in that environment—time is literally suspended. Can you give another example?

Iván Puig made a piece with seven scales, each with a book that has changed a paradigm in history: among them Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, Marx’s Das Kapital, the Mexican constitution, and the Bible. We say “el peso de la historia,” the weight of history—it’s the same idiom in Spanish and in English.

Arcángelo Constantini, Esférica, 2015, installation view. Photo: Rodrigo Hernández.

Iván Puig, Paradigmatic Disintegration, 2015. Give us a summation of the entire show, if you can.

The point of the entire project is how much we have culturally appropriated the idea of gravity to express so many things. “Gravity” in terms of meaning that carries more weight or things like “I am falling in love.” You can see how a physical force really informs a way of understanding not only the physical world but also the cultural and emotional realms.Is this part of what you proposed to the Russians? Did you have these ideas articulated?

Yes. We did not want to do science—we are not scientists—what we wanted to do was create new ways to perceive and understand something, which was gravity.How is this different from other art/science projects?

This was opening the discussion about how gravity, a physical force, really has a conversation with culture. The pieces are very conceptual. But in order to undertake them, we needed to experiment, to be in zero gravity, to change our perspective, and in order to do that, we needed a space mission, a zero gravity flight.

Mexican space artists in the Ilyushin 76 MDKaircraft with “exploding star” piñata. Installation view at El Laboratorio Arte Alameda. Photo: Adrián Cuevas. There was a scientist on your flight, Dr. Miguel Acubierre, who studies gravitational waves. Were there any artists that used science as a basis for the artwork?

Arcángelo Constantini was exploring speculative aspects of science. Lately he’s obsessed with the molecule of water and its memory. There is something called the Schumann Resonance—our planet has a certain resonance [relating to Earth’s electromagnetic field]. But since we have introduced global communications, it has changed the planet and its resonance, its life. Arcángelo asks us to consider how important the properties of [Earth’s] water are. The process was very scientific, but the results were poetical.

Okay, let’s talk about your work.

The concept was very simple. The piece comes from [wanting] to show the emotional side of humans when they are in extreme environments, alien environments, to show that we are still the same people that need affection and love.How did you come to this work?

I was very influenced by once when I was talking to an astronaut, and we were talking about feelings, he told me that in some cases astronauts are under contract and they cannot talk about certain feelings when they are in space. And I thought, well that’s rubbish! Of course, when they are in the space world they are like superheroes, but I wanted to see the emotional side of that. Also, with this project, it was so difficult to get to that point of being in zero gravity, I wanted everyone to stop focusing on switching on the camera or doing their own experiment, and change that into focusing on the ‘other’.

Zero gravity achieved! Installation view at El Laboratorio Arte Alameda. Photo: Juan José Diaz.

Nahum, Holding Air, 2015 Describe for us how you made such a piece on your flight.

So the piece is a series of embraces. When you have two bodies in zero gravity that try to touch each other and have that human physical contact, it also becomes a different thing because first you are floating and it’s like, how do I get there? You cannot swim, so you really struggle to grab the other person. And someone is upside down and another is in a funny position, so a hug becomes something else. And once you manage to grab someone, you notice that the body of the other person does not have any weight. It’s like holding onto air. You get very anxious about that, and you try to hold on more. And this becomes a beautiful action.How does this look in the gallery installation?

I made a video installation of three channels with these massive screens seven meters by five meters tall. I wanted to use the aesthetics of a music video, because music videos really enhance the emotions and they make things really dramatic. I was looking for that as well—real cinema, real space-love cinema. I composed some music, some romantic music, and then you have all these people struggling to hug each other, and then they go apart, and all the faces and the happiness, and the love. People are very touched by that. So it was about humanizing space as well. That’s my piece.

Marcela Armas, Geopsy, 2015. Photo: Juan José Díaz. I know that for many years you organized the massive London underground club in Victoria Station called The Shunt. Now you work with the UK-based Arts Catalyst on events like KOSMICA, a hugely popular space-art festival in Mexico City and London. But I understand that in 2014 you were also honored with the “Young Space Leader” award by the International Astronautical Federation. You told me you had just turned 35 years old.

Yes. What made the IAF award special is that it is the first time they gave the award to an artist, and also the first time to a Mexican.What are some of the space-related activities you’ve done leading up to this award?

I coordinate the committee for ITACCUS [focused on cultural uses of space], which is chaired by Roger Malina [son of JPL founder Frank Malina] and Nicola Truscott [founder of the Arts Catalyst]. Since we set it up back in 2008, we have been struggling to find our place in the space community. We have been concerned about certain topics—women in space exploration, and highlighting the relevance of societies that don’t have the context of a space race, in other words those without big space agencies and space projects but still engaging in an international discourse about space exploration. It’s important that we are also listening to them.

Left to right: Juan José Díaz Infante, Tania Candiani, Andreas P. Bergweiler, Miguel Alcubierre, Gilberto Esparza, Marcela Armas, Iván Puig, Ale de la Puente, Fabiola Torres-Alzaga, Arcángelo Constantini, Nahum. Photo: courtesy Nahum. How does KOSMICA also reflect this mission?

KOSMICA is a space and culture event held in different countries. It’s an interface where we can have a conversation about things that would otherwise be too radical or conceptual. To show people that they can engage in space activities even if they don’t have a rocket—they can still be part of it. It’s about humanizing space, bringing it closer to people.So scientists and engineers—space people—see you doing all of this and still finding time to make art!

I think the IAF really liked all this work, so I was humbled and surprised to get the award.Thanks for Skyping with us and good luck with the show!

Nice to see you, Carrie!

-

The Edge in CalArts Theater Festival

The annual CalArts-sponsored RADAR L.A. festival of contemporary theater had serious offerings this year of works outside the cultural references of the English-language. Some presentations were more successful than others, based purely on the dynamics and politics of using works in translation, or not. As it’s a significantly dense festival, this reviewer tried to contain her viewership to those works from South America, due to personal interest, and Japan/Oceana. These areas of the world seemed a diverse array of examples that could show something of how different theater companies dealt with the issue of presenting their works to the multi-cultural and worldly Los Angeles audience.

Stand out works were the Argentinian group Timbre 4’s Tercer Cuerpo (in Spanish) and Dogugaeshi from Basil Twist and Yumiko Tanaka, followed closely by El Año en que Nací by Lola Arias and his company of once-Chilean, once-children of the dictator Pinochet’s era. Interesting, but with significant issues (to be discussed) were You Should Have Stayed Home, Morons (Haberos Quedado en Casa, Capullos) and Stones in Her Mouth by the all-woman Maori troupe, whose insistence in presenting their two-hour show in Maori was not the problem at all, but rather the staging.

Tercer Cuerpo by Claudio Tolachir with theater company Timbre 4. Photo: Giampaolo Samá. Tercer Cuerpo (Third Wing) by Claudio Tolachir

This dynamic, humorous, and often-moving performance was excellent because of the characters, the actors, the script, the staging, the props, and the spare but important English translations projected on a highly visible but unobtrusive screen above and to the rear of the simple, effective set.

Five characters, whose lives slowly intertwine around each other’s secret personal challenges, and in some cases, shame, reveal their conditions over the course of the presentation as facets of economic and social crisis. A would-be father is really a child and can’t bear the thought of paying for dependents, so he seeks affairs. A talkative snoopy office-mate, full of false compassion for deaths affecting the lives of people close to them, has actually lost her home and is sleeping in the office; her ‘cell-mate,’ who seems the most prepared for life, reveals to her obstetrician that her husband is a fiction, and we realize at the same time as she that she might never have a child, her one hope in the world. Manuel has lost his mother; his lover; but later gains an absurdly youthful hair color, as he is forced “out of the closet.”

As the stage becomes more emotionally-pressured and self-contained—the lights flickering, the phone lines occasionally being cut-off—the spilling, boisterous Italian-inflected Spanish, being spoken at times by all the characters over the top of each other, paints a picture of a very particular kind of despair. The deflation of hopes is the living result of Argentina’s austerity measures, themselves the result of strict codes of behavior inherited by a society that deceived itself once under a dictatorship to preserve lives themselves.

The characters are resigned, together, to compassionately live out what is left of this fate they come to realize they unwittingly share. Because there are parallel story lines happening across and over the top of each other on a stage that “ruptures” and then is recomposed into the third (and forgotten) wing of the unnamed company, the translators took the liberty of indicating who was speaking when, so that even audiences with some or no Spanish could take in the entire gravity of the characters’ conditions. All the actors, but in particular those with the larger roles—Melisa Hermida, Daniela Pal, and José María Marcos—deserve a lion’s share of the credit for carrying this amazing show.

Left to Right: José María Marcos, Hernán Grinstein, Magdalena Grondona, Daniela Pal, Melisa Hermida. Photo: Giampaolo Samá. Dogugaeshi by Basel Twist and Yumiko Tanaka

This intriguing and beguiling puppet show tells of an old-world Japan crushed by modern life but reinstated through art and theater. This history unfolds through the representations and abstractions found in Japanese screen design—the screen itself becoming a stage, a curtain, and a character, as well as a backdrop to the larger losses incurred by the onslaught of modernity.

Told in what some might see as a characteristic of CalArts-infused media, the narrative is about a screen, behind a screen, behind a screen, behind a screen… at least five screens down, but maybe more. It became difficult to keep track of the literary device as the screens opened into an almost ludicrous infinity.

Thanks to someone in the sound booth who indicated the tiny pillows on the floor in front of the stage down front, from where one is supposed to see a puppet show, we got the full experience of Dogugaeshi. I feared anyone behind the fourth row would have needed binoculars, especially as it came to the fifth- and sixth-layers of screen. There, crucial information about nature’s inspiration for the ancient screens was revealed in patterned abstractions of water lilies, flowers, and water, which rapidly alternated during a retrospective and climactic moment of the story.

Dogugaeshi by Basil Twist and Yumiko Tanaka. Photo: Richard Termine. But to say that Dogugaeshi has a story line is to miss the point perhaps. The dancing, alternating, and shifting screens had a spatial fluidity that was representative of going back and forth in time, both literally in the narrative, and as one might do playing a piece of music, where modulations on themes or familiar refrains weave in and out of contrapuntal harmonies. Yumiko Tanaka, the show’s masterful co-creator, was this counterpoint. She sang and skillfully played extraordinary traditional Japanese music on a 13-string koto. Her kataginu, a formal kimono with oversize shoulder pads of the nineteenth-century Edo Period, was a stage set in itself.

That most American viewers could not understand the words to Tanaka’s songs—and they were nowhere translated—did not detract from the show, as it was brilliantly designed, paced, and staged so that one waited to patiently absorb the unfolding images and depths. The audience would wait for the “star” puppet, a dragon/fox character, to come across the stage, sometimes as silent commentator or as if it were a narrator, though the puppet’s presence was only occasional and really more of a charming, beautiful and emotive touch. The captivating drama infused throughout the work is also told through a series of four golden panels, who together formed a screen, or broke apart, or trembled; these felt like the most puppet-like characters—funny, absurd, playful.

Clearly Dogugaeshi has a narrative—the screens had to be built, the theater space they defined was on an island, which stayed protected in its pre-modern charm until a bridge was built, perhaps postwar, and the theater was forgotten within the loudness of new entertainment forms. The screens experienced the ravages of time, given in the image of a dragon and its chaos. A brief video “intermission” had a quickly translated 60 seconds of interviews with elderly women who told stories of the island, remembering how one could see the sun set directly on top of Mt. Fuji. This small, imagistic interlude could be almost forgotten, were not the focus of this article “translation.” Basil Twist and Yumiko Tanaka create a world where visual language, gesture and song interpret for us a story of loss and resurrection.

Dogugaeshi by Basil Twist and Yumiko Tanaka. Photo: Richard Termine. El Año en que Nací (The Year I Was Born) by Lola Arias

El Año en Que Nací (The Year I Was Born) by Lola Arias.

Photos: David Alarcón.Agentinian Lola Arias, the accomplished playwright of El Año en que Nací, worked together with a diverse group of young men and women who lived through the Pinochet era in Chile to create this informative, delicate play about the legacy of that country’s civil war, coup d’etat and subsequent dictatorship. Born between the years of 1971 and 1989, the actors tell their true stories; the stories (as much as they know) about their parents; and try to arrange themselves into a newly composited picture of the once-broken Chilean society.

Stories of exiles, tortures, and extrajudicial killings are sown through the personal stories and memories of children, who had nothing to do with their parents’ war. They create maps on the floor with chalk to chart the exiles; they banter, play at recreating events, bring out old documents, letters and clothes; and arrange themselves every now and then along different spectra to see where they fall—either by mother or father’s ideology, by class, by skin color. Punctuated commentary and bickering happen throughout, though it is clear they like and support each other, and each person is given their own time to talk personally. These testimonial moments are scripted, controlled, but still emotionally honest, revealing, sometimes shocking, at other times banal.

There are moments of surprise in the play and lots of humor. It is clear these children do not inherit the prejudices of their parents, and most have seen the deterioration of a parent that signed up too eagerly to fight for or against a Chile “más organizado” (as Pinochistas put it). Some of the stories resound with the irony of these conflicts: a young woman with a leftist father who “disappeared”—not in the political sense—finds him later to be given the excuse for having abandoned his children: “I’m sorry, but Pinochet fucked up my life.” Another, whose father supported Pinochet ideologically for economic reasons even though he was unemployed for ten years as a result of the situation, can no longer walk; he was at the far right in one spectrum, but in another goes far left when he reveals their house had a dirt floor.

Another father has gone paranoid. A mother, who used to have tea with Mrs. Pinochet, no longer speaks to her daughter; this brave soul, Viviana, went digging through records and found out the father she was told was dead is really in prison for his part in a brutal political killing. When he gets out, she says, she will ask him some questions. Another woman is still pursuing justice for her mother, an activist in the MIR revolutionary party, who was cornered in a house in Las Condes by 85 members of the police force, riddled with bullets (she came out shooting), stripped naked where she lay and was photographed as some kind of sick trophy. Heartbreaking moments like this were hard to bear for audiences who had similar histories, in Argentina, for example. For American audiences, some learning the extent of C.I.A. involvement in the coup, the reality is just purely untranslatable.

The play ends with a paralleling of each individual’s current struggles or milestones (one fought cancer, one came out of the closet, another finished her education) across a timeline showing Chile’s milestones. These young people are the survivors, they are a picture of a nation—there right in front of you, on the stage. They point out that Chile still carries the blood-stain of Pinochet’s call for “Libertad” on its still-circulating 10 peso coin; everyone in the country touches it, and flipping heads or tails for who will be the next President, it’s clear that the national currency symbolically betrays a long, if not impossible exit, from the country’s traumatic, decades-long “emergency.”

El Año en Que Nací (The Year I Was Born) by Lola Arias.

Photos: David Alarcón.You Should Have Stayed Home, Morons (Haberos Quedados en Casa, Capullos) by Manuel Orjuela

You Should Have Stayed Home, Morons is a structurally interesting work. Four monologues happen in four distinct sites in the city. For this version in Downtown LA, we started in a new civic pop-up park, moved to a slummy-bar and finished in a loft-apartment (not a new one), with one of the monologues occurring on the street below as we watched from above. But as it was, the LA version of the play was circumstantially limited by locations and actors. It’s curious why, in a city of so many Spanish-speakers, the complex language, word plays, and cultural references were ever translated into English.

Cristina Fernandez and Augusta Hirsch in You Should Have Stayed Home, Morons at Radar L.A. Photo: Steven Gunther. The first monologue was the most problematic. Delivered by Christina Hernandez, it was given in the park, recently completed by the looks of fresh plastic play equipment, a new lawn, and the modernist metallic benches with square blocks to keep people from sleeping on them. We listened to Hernandez explain frustrations to her young daughter (Augusta Hirsch) about motherhood, how it’s like “thinking with someone else’s head.” The performance was necessarily loud so that we could hear it, but with the dramatic infusion came an overplayed hand. When “thinking with someone else’s head” turns into a gory fantasy about taking off the heads of schoolchildren, making a mountain out of them and then having headless bodies recombine with the mismatched decapitations (and even a Chihuahua), the raving-in-English reaches a ridiculous crescendo. In Spanish, the absurd scenes described would be natural to the rolling fantastical language of magical realism (the writer Manuel Orjuela, like Gabriel García Marquez, is Columbian) and consistent with the Latin American context of horrors like the Guatemalan genocide and other anti-leftist “anti-terrorist” campaigns. In American English, there is no context for these images besides zombie movies, and I was not the only one groaning inside about the possibility of having to sit through three more monologues in this tonal range.

Thankfully the second, in a bar only a block from Skid Row, only suffered from emphasis. A drunk woman (Rachel Sorsa) opining philosophy to her passed-out mother (Sissy Boyd) about time passing insists repeatedly throughout the monologue that she be given a “glass with water” not a “glass of water.” But this emphasis is out of scale because to say “a glass of water” is not really a problem in English. In Spanish, the difference is starker; un vaso de agua suggests the glass is made of water. Bystanders in the bar, uninterested in the whole proposition, just left.

Sissy Boyd (sleeping), Rachel Sorsa in You Should Have Stayed Home, Morons at Radar L.A. Photo: Steven Gunther. The apartment location, where a homeless man we had seen wandering around our “tour” was then camped at the door, became the site of the second half of the play. The first monologue was his—expounding on what makes a good “beating,” and the beatings he likes to give. Having to scream the word “beating” up to the third floor, across the street with city buses going by, was a serious challenge the actor did meet. But the word—which was used often—is not a good English word to describe the violence of the act. In Spanish you can add the ending –tazo to words for extreme emphasis (paletazo, golpetazo, etc.), like a hand striking down the one being beaten. How I longed to hear this monologue in Spanish. The actor, Sal Lopez, did an excellent job with what he was given to work with, and we could even hear him over the buses. He also played well with the other people on the street, clearly seeing him as a raving lunatic, or someone looking for a ‘good’ fight.

Sal Lopez in You Should Have Stayed Home, Morons at Radar L.A. Photo: Steven Gunther. Finally, for the fourth act we then turned our attention inside the apartment. This was ostensibly a lesson from a father to his son about freedom, street smarts, and the trauma of growing up and losing one’s innocence. The actor, Adam Lazarre-White, had to drink a beer while delivering it, and he never lost an edge. His son (Phillip Solomon) sits patiently trying to get through The Catcher in the Rye before school. Solomon delivers the final coup d’grace of the play, “You should have stayed home, morons,” when his dead-beat Dad goes to bed and we realize we have spent two hours listening rather uncritically to adults spout their bullshit. Left with our pants down, we sheepishly applaud, loudly. I enjoyed the whole experience and the idea to stage a play in this way; however, with all that innovation into the form and delivery of theater, couldn’t someone have figured a way to subtitle the work so as to keep this play coherently in Spanish?

Stones in Her Mouth by Lemi Ponifasio/Mau

Radar L.A. audiences had the privilege to see the first public showing of the dense yet minimalist performance Stones in Her Mouth. Given that it will not premiere until December, there are not as many photos being made available for this work. Stones in Her Mouth is performed by Mau Company, a group of 10 Maori women, all of whom have studied traditional dance. Choreographer and creator Lemi Ponifasio had the concept to work with young women in Maori communities as a “leadership project,” and all of the songs and chants in the show are written by them.

Stones in Her Mouth by Lemi Ponifasio/MAU. Photo: MAU. There is barely any access for the audience to the world of the women, except where they want you to have it. The stage is open, no curtain, but at the start a blinding light projects out into the audience, forcing people literally to bow their heads. This light was intolerable—not a normal spotlight but some kind of halogen?—and if that was the intention, okay. But the problem was that it started setting off migraines and made people leave. The practical effect was to allow the women to step forward into the light when they desired, and to flow back into obscurity. The result—even with the light off, the purple tracers would not stop and the ability to see what was being presented suffered. Even though this light was taken out ten minutes into the show, a thin band across the back of the stage remained, which was still very hard on the eyes. The beginning of the work is so entirely slow that people could keep their heads down and look up intermittently; however, this destroyed the possibility of watching the deliberation and control of the women performing in one continuous stream.

Normally, I like the attitude of assaulting the audience; however, I’m not convinced it was the intention to make the work hard to see.

When the performers were closer to the front of the stage it was easier to look at the light, as there was something to focus on. So many of the performances were captivating, and proceeded from the central organizing idea of the Maori woman as story-teller, life-giver, and composer of moteatea (songs). The choreography emerged from the traditional female poi (ball) dance and gestures. The poi themselves were sometimes repurposed as devotional objects, or hidden in black sacks so their weight and movements would remain unexposed. The sounds they make hitting the body and the coordination needed by the women to synchronize the complex movements across the company were nothing short of impressive.

When I was in Rotorua, New Zealand earlier this year, I enjoyed attending a performance at a marea (cultural/religious house). In opposition to expectations for “cultures on display,” the kinds of explanations, smiles, welcoming, and education of those institutions were markedly absent in Stones in Her Mouth. Instead, the company’s expression is unfiltered and unapologetic. It is also strongly worded. The themes of the songs ran the gamut—from love to loss to defiance and anger. None were translated, but it was pretty clear. In one haunting piece a performer painted with a red cross (as in the British flag) across her naked body, becomes an abstraction of colonization visited upon the flesh. At the same time, nearly over her, another woman performs a strenuously energetic stick dance traditionally reserved for men. Women, it seems, have had to adopt multiple roles beyond the traditional, and there has been a cost.

The first human for Maori was a woman. Her name was Hineahuone, and she is invoked in a song cycle at the beginning of the performance. Woman is voice in the world of the Maori, which contrasts sharply with the title Stones in Her Mouth. The performance is as much about cultural loss, silence, and mourning as it is about cultural survival, language preservation, and the individual ideas of each of the composers. The searing white line the performers are constantly stepping over is an important symbolic element in staging the work. I hope those who had to leave because the right light frequency has not yet been found can come back to see all of Stones in Her Mouth another time. It will chase around my eyelids for a long time yet to come.