Vija Celmins’ work is best when you are caught by surprise—don’t read the manifest, just board the ship. Sublime encounters open quiet pathways to deep consideration of the now-octagenarian artist, her times and her legacy.

Celmins’ exhibition at Matthew Marks Gallery is steeped in matters of gravity in 40 years of her later works. Notably absent is her brief fascination with the age of televised war. Frank Sirmans’ writing (Vija Celmins: Television and Disaster, 1964–1966 [Yale, 2011]) should be called upon just for background—white noise—if only to remind us how Celmins has long considered art’s ability to fix death’s image.

Born in 1938 in Riga, Latvia, Celmins’ life has been circumscribed by war. Occupied by the Soviet Union until 1991, Latvia was an eastern outpost of the Nazi concentration camp system, a site of horrific executions by Einsatzgruppen death squads who left tens of thousands of Jews, Communists, and other “undesireables” in mass graves, yet the mention of Jews killed was forbidden by Soviet authorities. How can Celmins’ work be read against “suppression”? Many won’t know that Celmins was invited to create a work for the Hall of Witness at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; though not ultimately selected, her work, like that of Christian Boltanski, has a relationship to Holocaust memorials and, I posit, Riga’s adjacent Bikerniecki Forest, where a constellation of broken pillars memorialize the disappeared.

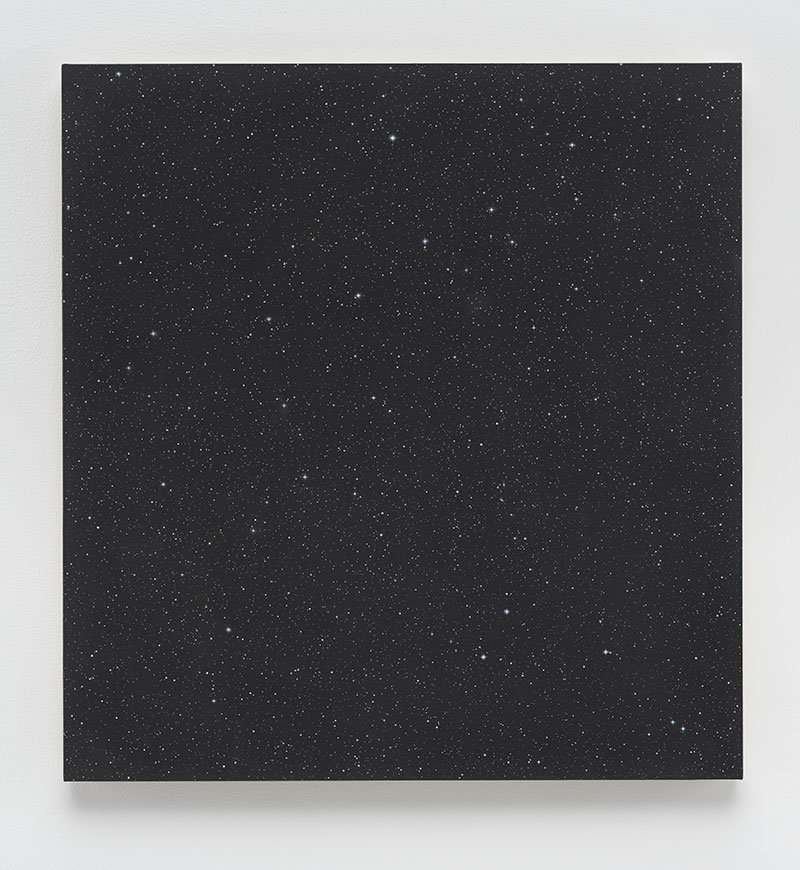

Celmins’ large canvases picture layers of deep space. Using thinly gesso-embedded stars, she pushes the comfort of a flat “readable” surface. These Hubble-like “windows” as in Night Sky #24 (2016), present galaxies so old they may be gone entirely. But our relationship to time obscures this from us. What do we learn from the errant paint-glop/star that wanders around the edge of the canvas? Looking at Celmins’ magnificent Blackboard Tableau (2007–15) installations of twinned chalkboards—one found and one fabricated—we find other indexical, extra-dimensional details like the gum of duct tape removed, copper nails buried with past force, scratches that mars the finish. The human hand wrote its sign, and it betrayed its violence. Lingering at the edge of the boards is the chalk’s ashen semi-solid state, somewhere between permanence and trace, memory and matter, the sign and its disappearance. “Little object a.”

The rhyme between the paintings and the blank slate of the tableau questions the impulse of energy required to start the language/universe over again. What would be different? What would be copied? What is inevitable?

The standout of the show is Two Stones (1977/2014–16), each palm-size and of a mass comfortable for a paperweight and place roughly 90 degrees to each other, where two hands seemingly just set them. The “real” pinkish granite echoes the stars with its white and black flecks, while the other, its twin made of bronze and painted, suggests only weight is the difference. But it’s impossible to know which is the mirror. It’s not just an inside joke or reprise of art’s nature/culture theme. The stones ask about the nature of time in reference to human flesh and ambitions, and suggest how possible it is to free energy with the sound of the two being struck together. Which will survive? The stone, or the artist’s great clap in an otherwise astonishingly silent oeuvre?