Your cart is currently empty!

Category: Cat Call

-

STREET ART ALIVE

STREET ART ALIVE is a 25,000 sq. ft. immersive “multi-sensory art and culture experience” that presents Street Art from Los Angeles and other major cities around the world. The interior entrance to the show features a recreation of an ‘80s New York City subway station with a heavily bombed (painted) train stopped at the platform. Although Philadelphia is often cited as the birthplace of modern graffiti, the installation neatly and attractively presents the premise that Graf and Street Art began in the train yards of NYC. The end of the faux-station segues into a simulacrum of another Graf shrine, London’s Leake Street graffiti tunnel, a 300-meter passageway that is the city’s largest legal wall. The end of this tunnel opens onto two large rooms of projections, which in turn lead to another series of rooms featuring an installation by Timbuctu State dedicated to disappeared indigenous women, a gorgeous installation of hand-painted murals by Dourone, and finally, a room with blackboard walls where one is encouraged to throw up a few tags of one’s own.

Subway station installation. Photo by Anthony Ausgang. Most of the art featured in STREET ART ALIVE is presented as large-scale moving projections on the walls and floor of the two huge open areas. Grouped by their cities, each artist is introduced with a brief biography and mission statement. Generally, the pieces are first featured in long shots to establish their urban context, then the details within them are revealed by “pan and zoom” effects. Some of these elements are further animated, which seems unnecessary as the pieces in the show are all first rate as they are. An “audio experience” soundtrack accompanies the images and runs the gamut from late ‘70s and ‘80s distorted punk/pop, break beats, and rap poetry, to contemporary musical stylings. The combination of the visual art and the music creates a controlled chaos that drives the 45-minute film; if not for the opening and closing credits, one would be excused for thinking it was either much longer or not looped at all. This is both a benefit and a detriment. In terms of quantity, one certainly gets one’s money’s worth for the $39 admission fee, but the unrelenting onslaught of beauty without respite becomes a bit wearying and its impossible to examine a favorite piece at length.

Street view of Berlin Wall sections painted by RISK. Photo by Anthony Ausgang

In an interesting remedy to the paradox that the art in STREET ART ALIVE is presented indoors, sections of the Berlin Wall have been installed on Broadway in front of the show. Before it fell in 1989, The Berlin Wall that divided East and West Berlin had become a major location for graffiti, most of it political. Although the wall was demolished, these sections were saved, and to make them more relevant to people who were born after the concerned events, Graf artist RISK was commissioned to paint new work on the obverse side facing the street. According to the artist, “with everything going on in the world and the historic importance of the Berlin Wall, I wanted to paint something that gave people hope for a bright future.” As positive as RISK’s addition may be, it’s worth checking out the reverse sides to see graffiti painted by locals when the wall still stood in Berlin, work reflecting an authentic expression of German zeitgeist at the time. With these relics, STREET ART ALIVE not only gives a valuable history lesson, but also a similar optimism for the future.

Reverse side of Berlin Wall sections. Photo by Anthony Ausgang.

STREET ART ALIVE at THE LUME LOS ANGELES

1933 S. Broadway, Los Angeles CA 90007

Tickets and information: https://thelume.com/losangeles/ -

NICE DOGGIE

Inspiration must have been in short supply the day in 2012 that Sue Williams started Dallas, her painting featured at this year’s Frieze art fair. Like most artists, Williams undoubtedly set out to create something unique, a painting for the ages, as masterpieces are often touted. But somewhere along the line it became, not the subject of a joyous collective experience, but confirmation of Williams’ onanistic creative process; her art fantasy apparently fodder for aesthetic masturbation. Consequently, if a Pollock drip painting can be called ejaculatory, then in the interest of gender equality this Williams painting is a gusher.

Sue Williams, Dallas, oil and acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 in., 2012. Photo courtesy 303 Gallery Amid the painterly chaos of Dallas, the head of a man peers out through the drips and smears that, quite literally, deface him. Even so, he is recognizable as a typical Feminist presentation of the classic “Fifties Man” white male oppressor. His degradation is to be expected of course, for Williams’ “world of provocative sexual politics” demands a sacrifice from the patriarchy. Also, according to a 303 Gallery press release from 2010, “Williams (work) can illustrate a conclusive and all-encompassing conjuring of everything at once.” Which explains why the blend of text, crude coproid brown blobs, and abbreviated diagrams in Dallas is essentially an upside-down roadmap to nowhere. Still, in the face of such statelessness, Williams has, like Google Maps, helpfully included the names of specific locations such as Throgs Neck in the Bronx and the Barclay Center in Brooklyn. That, plus pointless verbiage like, “luxury, privacy and the magic of Disney,” confirms that a whole lot of everything can amount to nothing.

Photo by Anthony Ausgang Other than the incontrovertible fact that brushstrokes travel in a certain direction, Dallas seems directionless. Perhaps that is why Williams felt it necessary to include the image of a dog’s asshole; something had to take this piece somewhere. And as far as remarkable totems go, an anus is guaranteed, as this blog evidences, to garner comment. Although her painting is indisputably High Art (why else would it be at Frieze?) the use of an asshole as a major element reveals a weak attempt by Williams to appear an anti-aesthetic revolutionary. Regrettably for her, Low Brow Art is often similarly scatological, but work done in that genre is generally structured around a recognizable narrative. Within that paradigm, a dog’s asshole is critical in understanding specific pictorial storytelling. That’s not the case in Dallas, where the anus seems to be included, not as an element necessary to deciphering this painting, but as a device for making it stand out from many otherwise similar paintings by Williams. As such, the anus may be fake news, but it’s a brilliant tactic. Still that’s about it; Williams’ oeuvre already proves that she’s adept in parlaying offensive content into a lucrative art career. But repetitious use of lurid imagery does lessen its impact; perhaps that’s why most people examining Dallas at Frieze didn’t seem to care about the canine sphincter. But that’s to be expected; after all, opinions are like assholes, and every dog’s got one.

-

None Dare Call It Art: The Drawings of Serial Killer Samuel Little

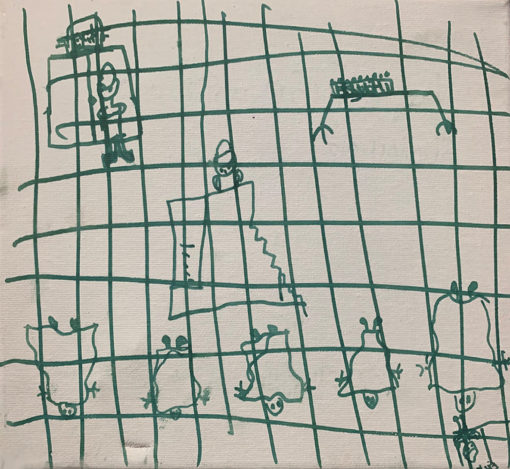

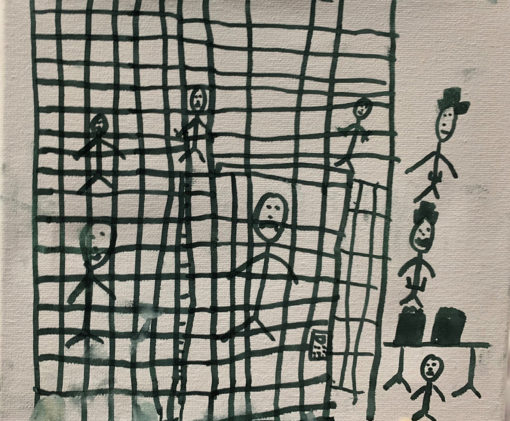

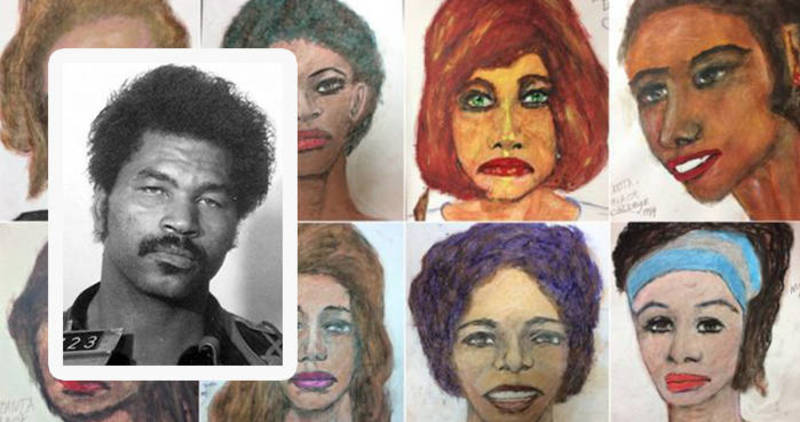

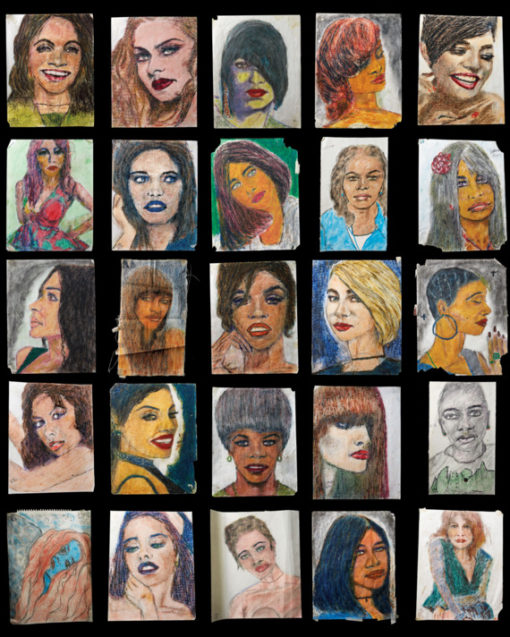

Samuel Little is by all accounts a despicable human being. Convicted of the strangulation murders of three women, he has confessed to 90 killings between 1975 and 2005. FBI agents who interviewed him said Little remembered his victims and the killings in great detail, but he could provide no help with dates. To overcome this problem, Little gave them pictures of his victims that he had drawn from memory, mostly marginalized women who were involved in prostitution and addicted to drugs. As a result of his confession and these drawings, 50 cold-case murders have been solved.

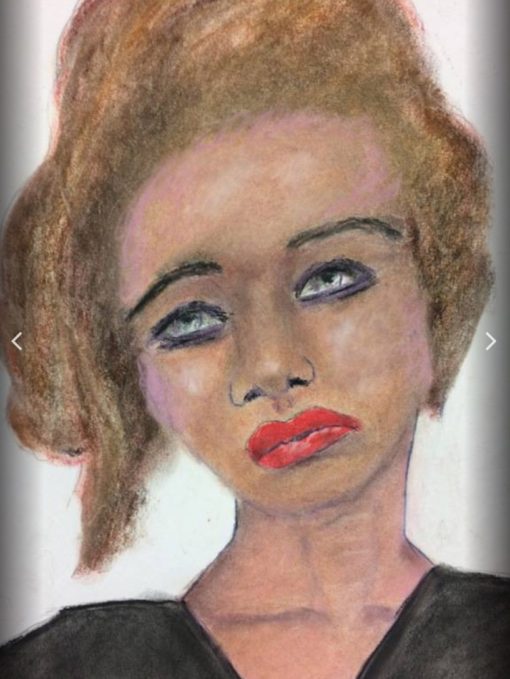

Samuel Little, date, media, and dimensions unknown Had he not turned out to be a notable murderer, and instead just a harmless unknown man in a room like Henry Darger, Samuel Little’s drawings would be rightfully praised as the work of a naïve virtuoso. But the most remarkable quality of Little’s drawings is the confirmed accuracy of his portraits, drawn and colored with the unschooled appeal so prevalent in Folk Art. By his own admission, drawing is his preferred pastime, and as a result he can “draw anything.” But since he now spends most of his cell time replaying the killings in his mind, it is “his babies” that he draws.

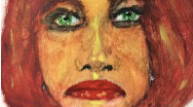

Samuel Little, date, dimensions and media unknown Still, there’s an eerie liveliness to these portraits of women who are now known to be dead, and their smiling faces conflict with the screaming death they suffered. That’s the horror of these things, and yet the wonder as well. The fact that years after their murders, this man was able to draw recognizable portraits of his victims, is difficult to parse. Had these women passed through his life untouched, Little’s astounding ability would be called genius and not madness. Unfortunately, this accuracy could only have come from observation of his victims over a lengthy period of time, and under disturbingly violent circumstances. If that isn’t grotesque enough, consider that in a prison interview with Jillian Lauren, Little states, “I live in my mind now. With my babies. In my drawings.”

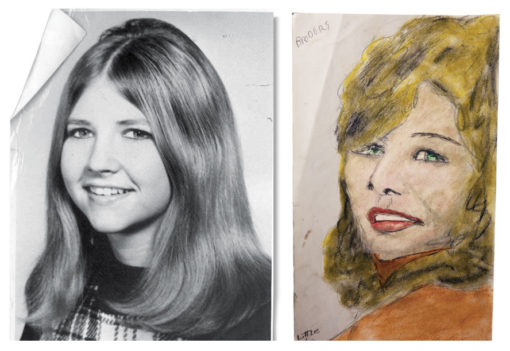

Denise Brothers, shown at left at age 15, was killed by Little in 1994, when she was 38. The serial killer John Wayne Gacy is probably the best-known murderer to make art; the paintings he made while incarcerated are sold and exhibited worldwide. But this success is based partly on kitsch appeal; most of his paintings are self-portraits of himself as Pogo the Clown, the costume and persona he adopted when performing at children’s parties. The financial proceeds that Gacy made from the initial sale of his paintings were given to families of his victims, and that utility arguably justifies calling his paintings art; after all, that is how they were promoted at the time and still are. The problem is that the word “art” effectively neutralizes the loathing for his paintings which should be preeminent. Art is an excuse for a lot of things; but cashing in on the suffering of the deceased isn’t one of them.

Collection of drawings bySamuel Little Unlike most drawings and paintings being made today, Little’s work serves a far greater purpose than mere wall decoration or the advancement of some subculture’s societal agenda. His drawings may have initially been made for his own perverse remembrance of the past, but now they serve to identify the people he brutally murdered, and it is this use that prohibits applying the word “art” to his drawings; very much the same way that a single-color canvas is considered art while a car painted an identical blue is not. And for critics and cultural analysts to call Little an artist is an honor he does not deserve; nor should “real” artists count him in their ranks. So, in these times, when Art has become the aegis under which so many meaningless things gain stature, it’s good to be reminded that some things cannot be called art; and remembering the dead should not be a spectator sport.

Samuel Little, detail of portrait -

Feminihilism

Feminism is an ideology that powers political and social movements dedicated to establishing gender equality between men and women. As such, it serves as inspiration for artistic exploration of the various issues involved in that process. First-generation feminist artists like the late Carolee Schneeman, rejected the male-dominated scene of the 1970s, refusing to be, in her words, “cunt mascots on the men’s art team.” Forty years later, the changes advocated by these pioneers have created a new generation of women artists who don’t identify as feminists. This attitude is perhaps best represented by the “women initiated” NGO, Code Pink, a “social justice movement” that encourages people of all genders to participate in its activities. The importance of the inclusion of men in such organizations cannot be downplayed, as it shows that many Millennial women believe the era of close-combat for gender equality is over. For like-minded women artists, this means that their starting point is no longer the difference between the sexes; in fact, male privilege doesn’t even chart as an issue. While emphasizing the obsolescence of binary sexual identities, Feminihilism simultaneously dictates the abnegation of any masculine influence on Millennial women artists.

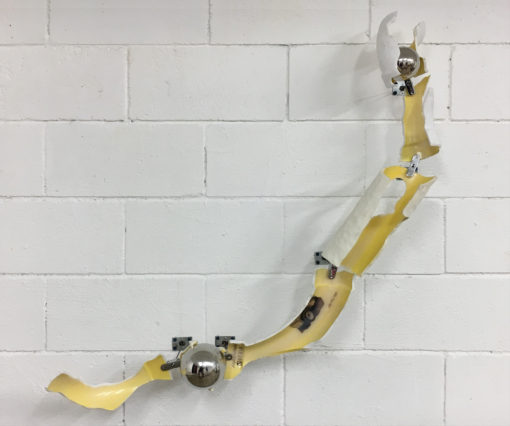

Sofia Sinibaldi, Untitled, mixed media, 36 x 36 inches, 2019. Photo by Anthony Ausgang Considering today’s culture wars, any work of art done by a woman has societal implications. In AX, their two-person show at the Red Zone gallery, Natasha Romano and Sofia Sinibaldi neatly evidence an aesthetic allegiance to their gender. Both artists have unique approaches but the absence of sexual politics in their individual works confirms their commitments to a strictly feminine paradigm. Consequently, Sinibaldi’s sinuous wall sculptures are reminiscent of the blocked fallopian tubes symptomatic of an ectopic pregnancy, and the flood of red grounding Romano’s floor sculpture suggests menstruation and/or sexual violation. Still, the heart-shaped negative space she employs registers a modicum of romance, but there’s no indication whether that’s hopeful or ironic.

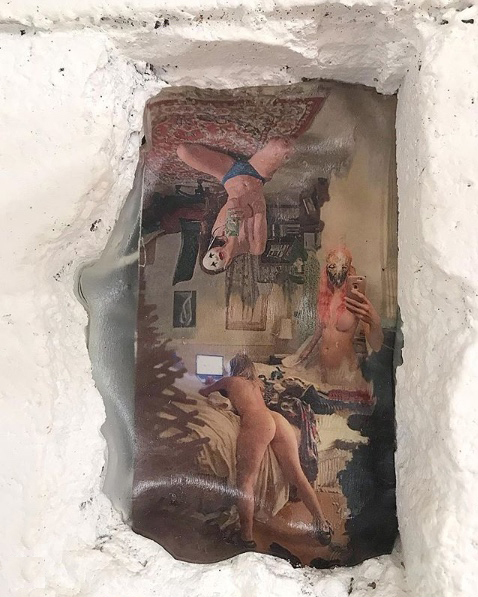

Natasha Romano, 1 2 3 red blond brunette anon screens, mixed media, 2019. Photo courtesy Natasha Romano As Millennials, both artists use contemporary vernacular when problem solving. So, it’s not surprising that Romano’s wall piece, 1 2 3 red blond brunette anon screens, addresses self-identity issues via the depiction of social media. Two of the figures are taking selfies but their faces are paradoxically obscured by masks, essentially promoting anonymity over individuality. The third figure, although she is communing with a computer, is isolated by her lack of a phone, putting her more in the role of a lurking observer than participant. However, maybe that duality is what appeals so strongly about the internet; playing both parts can have a heady appeal.

Natasha Romano, Diamond Headed Honey Snake, mixed media, 72 x 48 x 48 inches, 2019. Installation photo by Anthony Ausgang But the main piece in AX is Romano’s magnum opus, Diamond Headed Honey Snake, a mixed media floor sculpture that dominates the gallery. Describing herself on Instagram as “sculptress n garmentiste”, in this piece Romano makes smart use of the skills she gained as a seamstress assembling her clothing patterns from non-traditional fabrics. Consisting of small cairns, rattlesnake rattles, natural and synthetic materials, and lots of different dried red sludges, the sculpture is epically incomprehensible. But perhaps being psychically cast adrift by this “shock of the new” is the reaction Romano expects, because with her multi-faceted talents, she rewards scrutiny with devilish and bizarre details. In just one part of the sculpture, a flaccid snakeskin encrusted with wasp’s nests that ooze plastic is intertwined with sewn-together vinyl strips featuring figurative emoticon-style hieroglyphs. This accumulation, held aloft over the dry red tide by trestles that look like webs made by spiders on meth, disappears into a mysterious box from which the spill emanates. As a piece on its own, it’s impressive; as a component of the whole assemblage, it’s spectacular.

Natasha Romano, Diamond Headed Honey Snake, mixed media, 72 x 48 x 48 inches, 2019. Detail photo by Anthony Ausgang In terms of cultural progression, today’s art would not be possible without the efforts of previous generations. But whether or not contemporary artists actually owe any acknowledgement of that is debatable. After all, at this point do we still really need to thank 19th Century French Impressionists? The trick, as both artists show, is to update the message; perhaps that is honor enough.

Red Zone, 840 Chestnut Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90042-3041

Open by appointment (818) 524-8701

-

FLUXUS ON THE VERGE OF A NERVOUS BREAKDOWN

In many ways, opera is the high point of the Western classical music tradition. Originating as royal entertainment in Italy at the close of the 16th century, opera evolved to become fashionable throughout Europe. This remained the status quo until the early 20th century, when the development of motion pictures and changing public taste relegated opera to the domain of the art-conscious upper class. As such, it was prone to “cultural upgrading” and composers like Schoenberg introduced atonality and other variations. Such High Art innovations did more to confuse than clarify the position of opera in modern music, so by the latter part of the 20th century, it was clear opera needed to be modernized in a more popular way. Avant-Pop arbiters like Peter Sellars began staging operas in new ways, like his 1980 production of Don Giovanni, cast, costumed and presented as a blaxploitation film, complete with nude actors and heroin addicts. As it would turn out, once this thematic Pandora’s box was opened, every kind of bastardization of the artform became possible in the name of forward aesthetic progress.

John Cage, Europeras 1 & 2, Photo courtesy Craig T. Mathew / Los Angeles Philharmonic Not to be outdone by such wild musical youngbloods, the venerable composer John Cage decided to apply his personal brand of deconstruction to opera, and his 1987 Fluxus work Europeras 1 & 2 was the result. Currently directed by Yuval Sharon and staged in Culver City at Soundstage 23 in the Sony Pictures Studio, the production is hyped as “an opera of independent elements… determined by chance procedures.” So, although the orchestra was under strict directions to play “the actual instrumental parts in the literature”, Cage allowed the singers to belt out whatever aria they chose for as long as desired. Which basically means that the audience was subjected to a high-end clusterfuck of snippets of operatic arias, mixed and matched elaborate costumes, and non-existent stage direction, all of which was periodically interrupted by an overwhelmingly loud recording of Truckera, a tape of 101 layered fragments of European operas. None of the characters onstage related to one another, and even their accompanying props had nothing to do with their timeframe or identity; at one point, a nun with a surfboard stood at the edge of the stage, peering into the audience as though judging distant waves. Unfortunately, even in the Fluxus tradition such cheap laughs only fill ocular time and space until the next heresy, so this senselessness became disconcertingly boring after 90 minutes without pause. Perhaps in anticipation of this, the second segment of the opera promised two sections of supposedly refreshing silent, general inactivity. Even so, judging from the exodus during the intermission, an opportunity to hear a sample of Cage’s smash hit 4’33” wasn’t much of a motivator to stay.

Stories, Rachel Guettler in Room 14 at the Rendon Hotel, photo by Anthony Ausgang Meanwhile, in Downtown L.A., a far less self-aggrandizing manifestation of operatic disconnection was taking place. Directed by Ralph Ziman and staged at the under-renovation Rendon Hotel, Stories presents actors in separate rooms engaged in activities as equally unrelated to each other as those in Europeras 1 & 2. The difference between the two productions is that while Sharon defies the audience to find any narrative in Cage’s visual and sonic cacophony, Ziman encourages such speculation; in fact, figuring out what’s going on is the whole the point of the experience. It’s a great idea, but the lack of any unifying element other than location make it impossible to connect the separate elements. It also doesn’t help that the majority of the acts are obviously by non-actors subscribing to the myth that calling something Performance Art excuses lack of professionalism. Fortunately, there are exceptions: in room 14, opera singer Rachel Guettler successfully presents herself as, well, an opera singer, later duetting marvelously with baritone Kenneth Enlow on an outside roof; and in room 20, Johnny Cubert White convincingly natters away in his room like a tweaker in the beginning stages of a meth binge. But the relative success of Stories lies in its lack of pretentiousness; when the going gets Lowbrow, the Lowbrow get going.

Stories, Johnny Cubert White in Room 20 at the Rendon Hotel, photo by Anthony Ausgang Stories allegiance to its low roots ultimately makes it more interesting than Europeras’ claim of High Art, but it’s equally frustrating to experience. There are reasons that stage direction, plot, and developed talent are essential to calling an event opera or theatre. Without them it’s just like Humpty Dumpty, and no amount of deconstruction will ever put it together again.

Featured image of Rachel Guettler courtesy Andy Romanoff

Fluxus: Cage’s Europeras 1 & 2, Sony Pictures Studio, November 6, 10, 11, 2018

Stories, Rendon Hotel, November 9, 10, 11, 2018

-

Cover Versions

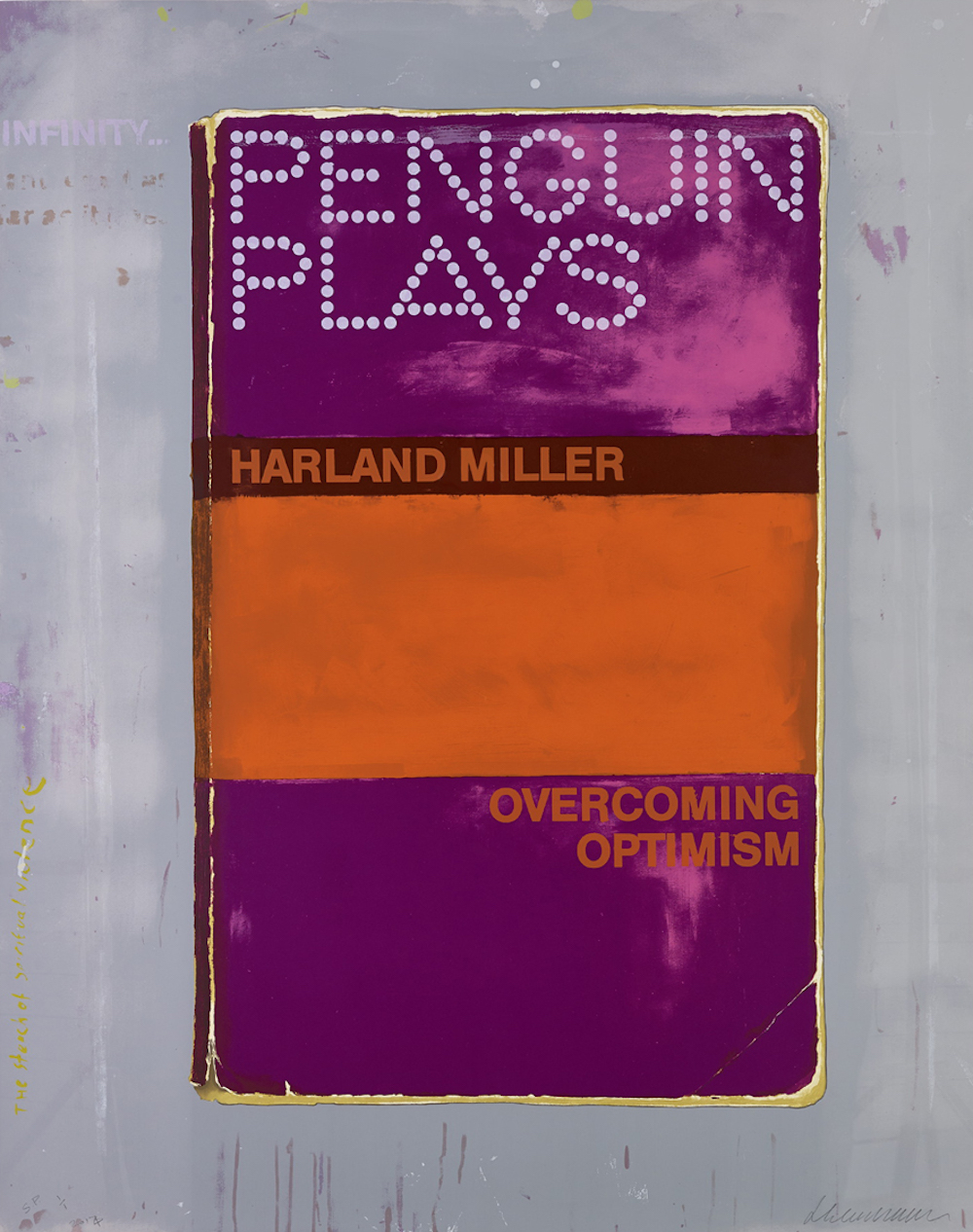

Like many Pre-Millennial truths that were once irrefutable, the adage, “Don’t judge a book by its cover” is waning into obsolescence. After all, what is the utility of a book cover in the era of e-books that claim neither form nor substance? In his exhibition “Overcoming Optimism”, the artist Harland Miller obfuscates the issue further with prints of his paintings of vintage Penguin paperback front covers modified by what the artist assumes to be hilarious puns and helpful maxims for the iGeneration. The images that Miller has decided to paint are hardly demanding; in fact, they’re so visually and conceptually facile that the Ikon Ltd. press release resorts to claiming that “Pop Art, abstraction and figurative painting” were all involved in the creation of these “cover versions”. Classic Penguin paperbacks often sported covers by noted figurative artists such as Norman Thelwell and Margaret Belsky, but don’t look for any coy appropriations of their illustrated covers here as Miller doesn’t seem up to the challenge.

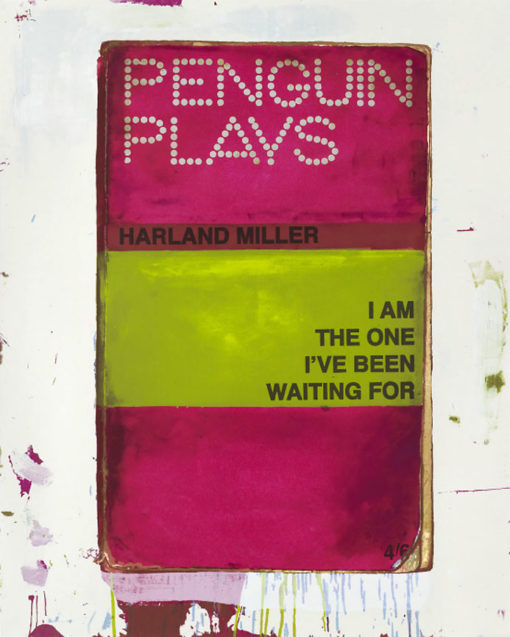

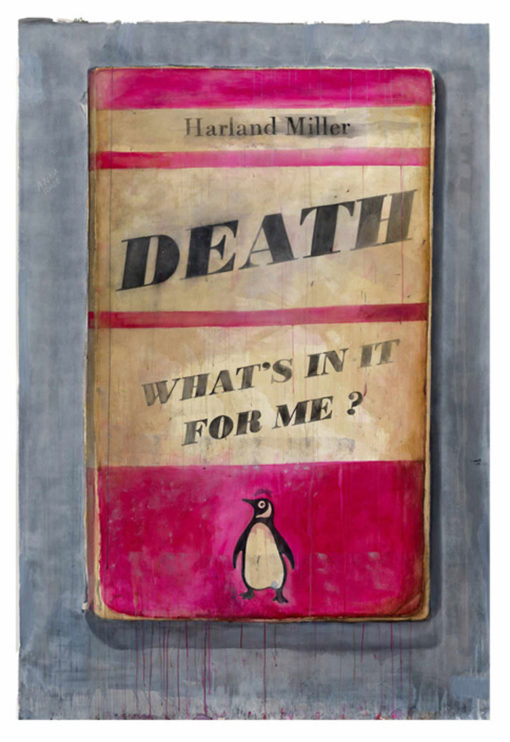

Harland Miller, I Am the One I’ve Been Waiting For, 2012, 49 1/8 x 39 3/8 inches, Silkscreen print, Edition of 50. Photo courtesy Ikon Ltd. Born in 1964, Miller is firmly a member of Generation X, but several pieces in this show replace his age group’s characteristic skepticism with Faux-Millennial egocentrism. In the piece, “I Am the One I’ve Been Waiting For,” Miller deftly uses the first-person singular to ungraciously introduce us to his psychic onanism. Meanwhile, the print, “Death, What’s in it for me?” evidences how the Grim Reaper’s ultimate threat has been neutralized by the Millennial belief that, while previous generations had to cheat Death to avoid it, all they have to do now is ignore it. It’s reassuring to know that, so long as men can breathe or take selfies, Death shall not brag thou wander’st in his shade. Still, it’s not clear if the appeal of this print is Miller’s arrogant questioning of Death’s function and how it affects his ego, or bravery the spectator hopes to osmose from such braggadocio.

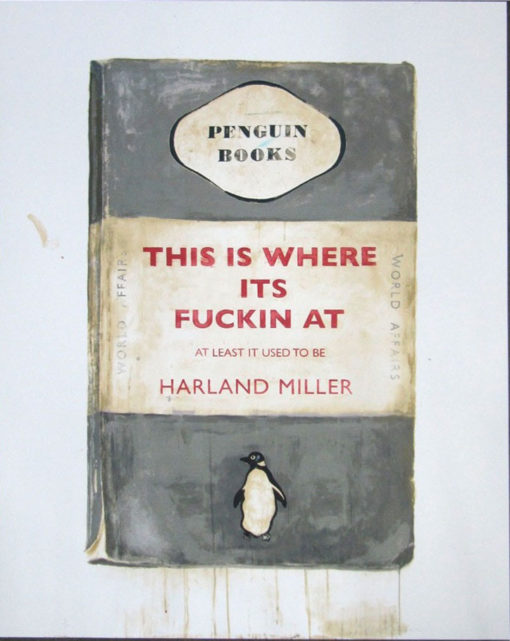

Harland Miller, Death, What’s in it for me?, 2011, 37 13/16 x 26 inches, 10 color silkscreen print, Edition of 50. Photo courtesy Ikon Ltd. Other prints in the show deliver book titles that neither inspire nor intrigue after their moment of kitsch appeal fades. “This is Where Its Fuckin’ At,” may give the GPS coordinates to a hipster Nirvana, but such a claim is meaningless in a consumer society where just about every product makes the same assertion. “Blonde But Not Forgotten” is essentially a one liner that steals its laughs from other jokes, as is the stoneresque “There’s No Business like No Business.” Still, with titles like these, its a shame that the gallery doesn’t have Miller’s “critically acclaimed” books available as it would be interesting to see how long he is able to maintain this wordplay.

Harland Miller, This is Where Its Fuckin’ At, 2012, 56 1/2 x 43 1/4 inches, 15 color screenprint, Edition of 50. Photo courtesy Ikon Ltd. Maybe it doesn’t matter that these compositions are graphically derivative and inspirationally flat. Or that it’s a middle-aged man playing a Millennial game in an attempt to come across as a smarmy sage. What matters is that if one can’t judge a book by its cover, all that’s left to judge is a cover without its book.

Harland Miller, September 8 – November 3, 2018

Ikon Ltd., Bergamot, Gallery D3, 2525 Michigan Ave., Santa Monica, CA 90404

(310) 828-6629, http://ikonltd.com and http://instagram.com/ikonltd/