Your cart is currently empty!

Category: **MAY-JUNE 2023

-

BUNKER VISION

Watching the HitsTwenty years before MTV aired its first music video, people were making short films of bands and singers performing their hits. The ones from France featured A-list acts and production values. Italy gave us the best film documentation of Screaming Lord Sutch. The American one that has best survived the test of time is Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made for Walking.” Although the American films were filmed in Techni-color (which tends to not fade over time like other stocks) the production values were often cheap. They usually featured dancers in bikinis who might or might not be dancing in sync with the music. How did these films come to be?

In the late 1950s a new kind of jukebox started showing up in French cafes and clubs. These jukeboxes (called Scopitones, later rebranded for American audiences as Colorama) showed films of musical acts on a screen the size of a modern laptop. Because these machines were placed where young people congregated, the acts they featured were the actual hitmakers in films that were geared toward thoughtful music fans. We have these machines to thank for the existence of high-quality films of Serge Gainsbourg, Johnny Hallyday and Françoise Hardy. When the Mafia (purportedly) brought these jukeboxes to America, they situated them in men’s clubs, where the music of the day mattered less than the jiggling assets of the dancers. Most of the American titles were filmed between 1965 and 1968. The most prestigious rock acts to be recorded were Procol Harum and The Moody Blues. Most of the other acts were cover bands and B-listers. One of the most fondly remembered performances is “The Web of Love” sung by actress/model Joi Lansing. The number is performed inside a spider web and a cannibal’s cook pot. It has become a YouTube staple. In fact, the gonzo manner in which the American musical numbers were recorded caused Susan Sontag to include them in her canon of camp.

Film jukeboxes actually have a longer history in the US. In the early 1930s there was a technology called Pan-O-Rams. It was a sort of visual jukebox that featured hot jazz films. A key difference with these was that all of the films were spliced into one long loop, and the film for your coin was whichever film was next. It is estimated that about 1000 to 1500 Scopitone machines made it to the United States. Most of the ones that survived got repurposed. There are currently machines in the visitor center at NASA. As of this writing, a working machine fully stocked (36 films) is being offered on eBay for $7500. There is a huge gray market in DVDs of old Scopitone films, and new titles show up on YouTube almost weekly. There is such a specific aesthetic associated with these films that artists making videos today will ape them for a carefree ’60s retro feel. It is currently estimated that about 72 titles were made in the United States. When a new title shows up in a collector list, or on YouTube, there is the sense of occasion that is often caused by the discovery of a lost silent film in a Norwegian attic.

-

From the Editor

May/June 2023; Volume 17, issue 4 Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,“Art about art is elitist,” my boyfriend in grad school used to tell me. But if that was the case we wouldn’t have AbEx, Minimalism and maybe even Conceptualism. I got it though: The art world with its various trends and movements could seem precious and pretentious. Even so, I did love painting for painting’s sake. Some would say I excelled in the non-representational art form. There’s nothing like a great abstract painting. I’d kill to own a Brice Marden.

But what about all the injustice and malaise we see today; can we really just make art that is only about art? As artists, isn’t it our duty to be addressing larger concerns? Our “Public Display” theme in this issue includes artists who consider their community and the world around them—recognizing the importance of engaging with their surroundings, they want to give something back.

Some art venues fall into the category of nonprofit organizations, which, thankfully, get the help of residents who serve on their boards and grants allotted from municipal funds. One such place is the community-building organization in Leimert Park, conceptualized by South LA’s own Mark Bradford, Art + Practice. Alexia Lewis catches up with the A+P team who run programs for teens and award several scholarships, among many other altruistic endeavors. Regular online columnist Lauren Guilford interviews Jessica Taylor Bellamy, whose work deals with LA’s unique eco-phenomenology. And our cover artist is San

Francisco–based Andy Freeberg, featured and written about by regular contributor William Moreno. Freeberg delves into the commercial aspect of the art world and exposes the machinations of that milieu—unsurprisingly it isn’t very different from any other free-enterprise world.I’ve often felt that Artillery plays a role in serving our LA arts community; at least we try like hell to. And LA gives back in buckets, especially our loyal supporters. With that in mind, I’d like to announce an important addition to our staff: our new publisher, Alex Garner. She hails from New York City where she worked at Artforum for several years, and MoMA—a little New York in our mag couldn’t hurt anyone, right? Alex knows the ins and outs of the art world and recognizes its complexities—how small it can be, yet expansive at the same time. The LA arts community is where Artillery’s heart really is and Alex is aware of the significance of our city as an art-world center, equal to New York. (Just look at all the New York galleries moving here!)

Exciting new things are in store for Artillery with Alex on board. She already has an online art column in our weekly newsletter, The Publisher’s Eye. I couldn’t be happier to begin our collaboration, putting our heads together to better serve the LA art scene. We know how important that is, and how important Artillery is to LA.

It’s hard to believe that in the 16 years I’ve run this publication (with the help of our loyal contributors and employees), things just keep getting better. Owning an art publication may seem provincial, even elitist, but I can’t help but think there’s some good that comes out of it. Art for art’s sake, anyone? We’ll take our chances.

-

Village Mindset

Innovative Community-Building at Art + PracticeIt has long been the rule for nonprofits of all kinds to create and maintain paternalistic relationships with the causes and communities they claim to serve. Unfortunately, there are several arts nonprofits that fit this bill. So it’s refreshing to catch up with an organization such as Art + Practice, which has directly contributed to positive and long-term impact in the majority Black community in Leimert Park, since its founding in 2014.

Art + Practice’s partnership with First Place for Youth is providing support to anywhere from 85 to 100 transition-age foster youth at any given time. Their collaborations with institutions such as the California African American Museum (CAAM) and the Hammer Museum bring free arts programming to South Los Angeles while promoting artists of color. Their most recent collaboration began in 2022 with PILAglobal, a nonprofit dedicated to providing educational support to children and families experiencing global forced migration. Partnerships such as these are noble and necessary, but they aren’t automatically effective just because all parties involved want them to be, or say they are. So then—in places where these collaborations have had true impact as intended—what has been the driver of these successes?

Installation view of “Thaddeus Mosley: Forest” exhibition at Art + Practice. It starts with how much honesty any business or nonprofit entity brings to its mission. Art + Practice is the brainchild of Black artist Mark Bradford, who still lives in South LA, where he grew up. From its very founding, A+P has been an extension of Bradford’s citizenship in South LA, demonstrating what it looks like to lead with a “village mindset.” “The village serves as another element of home,” says Thomas Lee, the director of First Place for Youth. “How do we create a greater sense of home with immediate services, but also expand that sense of home in the larger village of our communities and our society?”

This high level of intentionality present at every level of First Place’s operations is coupled with A+P’s provision of almost-free space for services right in the Leimert Park area and generous monetary backing: over $100,000 a year in scholarships and support for youth aging out of LA’s foster care system, most of them Black. This shows up for scholars as individual support in pursuing their education and employment goals; onsite job shadowing opportunities with A+P’s team to provide opportunities for First Place’s young adults to see what it’s like to work at a nonprofit arts organization; offsite job tours at large-scale businesses; roundtable discussions with leaders in their field of expertise and events celebrating their successes.

As a result, youth graduating from the transitional program go on to enjoy continued growth and success in just about every walk of life. In fact, anywhere from 10 to 15% of graduates go on to pursue the arts professionally.

Exhibition Walkthrough of

“Deborah Roberts: I’m”

at Art + Practice.Sophia Belsheim, who has been with Art + Practice since its conception and has worked her way up to the director position, feels that the organization’s very targeted mission and vision attracts similarly focused and welcoming people. “There’s this amazing connection to the community that’s very direct.” she says, referencing Bradford’s ties to Leimert Park and co-founder Eileen Harris Norton’s origins in Watts. “They understand it. They’re not just coming in from the outside but working within. That’s something that’s always captivated me since I’ve worked here,” she continued. New initiatives are launched only after assessing the needs of the community, taking care not to displace any existing businesses. The goal is for people to view the A+P gallery space as a conduit to engaging with world-class art while out and about grabbing coffee, buying books and doing the everyday things that people do—no pressure to purchase anything.

The main determining factor is the impactful partnerships A+P launches, treating them like genuine friendships you treasure. When speaking of the staff at the CAAM, who she’s working with on their five-year collaboration, Belsheim says, “They are incredibly thoughtful about how to conceptualize their programs and they bring us into the dialogue, and that feels like a true collaboration. I think where collaborations tend to not work out is when there is dictation—when it’s not about openness and welcoming.”

According to the US Supreme Court, corporate entities are people, and the Citizens United ruling by the same court has declared that money equals speech. There is a dark side to the consequences of these laws, and yet there can also be a light side—it’s simply a matter of choice. Accordingly, we can view A+P as a person who chooses to put their money where their mouth is, who embodies the characteristics of a respectful neighbor and thoughtful friend, and who uses their position and privileges to benefit the peers within their community. And this is all because A+P’s founders allow it to be an extension of their own village mindset.

-

Extra Flavor

Desert X Breathes New LifeIn another sign of an unusually wet winter in Southern California, the desert and foothills of Coachella Valley are painted a lush green, the tops of the San Jacinto Mountains dusted with a few inches of stark white snow. It is against this startlingly serene backdrop that the 2023 iteration of Desert X, a young and ambitious biennial, blossoms across the sun-kissed Fantasyland of Palm Springs.

Departing bright and early for the press preview day on March 3, I made the two-hour drive east from Los Angeles to the Desert X hub at the Ace Hotel & Swim Club to enjoy refreshments under the sun and hear opening remarks from this year’s organizers.

There’s a saying attributed to the Kwakwaka’wakw nation that artistic director Neville Wakefield used to frame the exhibition: “A place is a story happening many times.” In recognition of the force humans exert upon the natural world, the 12 international artists selected for this year’s presentation by Wakefield and co-curator Diana Campbell serve as documentarians of the stories and mythologies as historic and encompassing the desert holds.

To the curators’ credit, this year’s artworks move away from replicating the legacies of land artists like Robert Smithson and Walter De Maria who once dominated the American West. Instead, it foregrounds women and artists of color whose work recontextualizes our connections to the desert and amplifies issues of social and environmental justice in greater depth, breathing new life into the arid landscape.

One such work comes from Tshabalala Self in the form of Pioneer, my first stop of the day. In a provocative interpretation of a commemorative equestrian statue, a disembodied female torso with legs triumphantly splayed across the back of a kneeling horse displaces the classic image of a macho colonialist on horseback. The monumental bronze sculpture was built in homage to Black and Indigenous foremothers whose bodies and labor allowed contemporary America to develop. Its placement, nestled away in a shady grove at the end of a sandy, half-mile hike through Desert Hot Springs, echoes how the histories of women of color were shunned away from city centers—and thus, our collective consciousness. But here, the sculpture’s assertive presence celebrates the rightful place in the American landscape of all the marginalized groups it represents.

Next, I made my way a few miles north to Mexican artist Mario García Torres’ Searching for the Sky (While Maintaining Equilibrium). Another short hike from the parking area later, the desert gave way to a herd of mechanical bulls made of skyward-facing metallic sheets reminiscent of solar panels writhing out-of-sync on electric pedestals. I climbed to the top of a nearby dune and watched aerially over Torres’ clever commentary on cowboy culture, searching for patterns in the bulls’ movements but eventually settling on the futility of humans attempting to harness any semblance of control over these wild animals or the unforgiving environment we found them in.

In a cinematic experience activated by driving along Gene Autry Trail, I encountered an equally poignant sequence of billboards featuring photographs by Tyre Nichols, the 29-year-old Black man fatally beaten by Memphis police in January. Each photograph in the series titled “Originals” stands out within the desert empire of roadside signs, advertising unassuming and hopeful images of landscapes, sunsets and architectural spaces, yet tinged with reminders of the roadside violence that claimed Nichols’ life too early. Arranged at the last minute, the work is a nod to the curators’ commitment to centering social issues and a continuation of the biennial’s tradition of utilizing billboards as sites of artistic expression blended into the existing desert infrastructure.

Desert X 2023 installation view, Tyre Nichols, Originals, GoFundMe Tyre Nichols Memorial Fund, photo by Lance Gerber. Gerald Clarke’s Immersion is the installation most deeply rooted in the indigenous history of the region. A university professor and local Cahuilla tribal leader, Clarke has constructed a monumental maze-like gameboard atop a woven straw apparatus he describes as “like Native Trivial Pursuit.” The interactive piece comes with a set of custom playing cards with trivia questions based on indigenous intellectual tradition, a design that, Clarke conceded, would give the average American visitor a hard time and compel them to cheat—just as they have cheated Native peoples out of just about everything. As he predicted, I found it nearly impossible to navigate the walk-on boardgame in the manner Clarke intended and had to stop myself from giving in to my inclination to simply google the answers. But I was rewarded with new ways of viewing the landscape and brought home with me a reminder of erased local histories, as well as a desire to do better in educating myself.

After a quick detour for a poolside Spanish lunch, I embarked eastbound to Cathedral City for my next stop at Sunnylands Center, whose botanical gardens host Amar a Dios en Tierra de Indios, Es Oficio Maternal by Mexico City–based artist Paloma Conteras Lomas. The installation centers on a silver 1991 Chevy Caprice that has seemingly broken down among the cacti. A vibrant tangle of plush textile forms—including stuffed sombreros, phallic forms bearing stuffed guns, clumps of flowers and furry clawed limbs—erupt from the vehicle’s windows, windshield, roof and trunk, spilling onto the manicured lawn in absurdist fashion. I took a moment to sit in the car’s back seat, where

Lomas included an audio-visual component, and was overcome with the odd sensation that I was a hapless passenger being stewarded toward my impending doom by a playful cast of alien characters. In contrast to a softness that invites children to hug its billowing appendages, the work addresses heavy topics of class violence and colonial guilt with a tongue-in-cheek lightness.Located a five-minute drive east of Sunnylands came one of the most powerful installations in the biennial—British-Bangladeshi artist Rana Begum’s otherworldly No.1225 Chainlink. Responding to the ubiquity of the chain-link-fence pattern seen across Coachella Valley, Begum reclaims its dual associations of protection and exclusion: Her labyrinthine installation combines harsh industrial materials with the meditative, ritualistic experience visitors get from meandering through a concentric pavilion she has built out of chain-link fences painted bright yellow. What at first feels like a claustrophobic spiral proved to be an expansive rather than reductive structure, with the center giving way to a clearing that allows people to flow through the enclosure just as easily as wind, water, sand and sunlight filter through the repetitive metal slots. Flanked by rolling hills and miles of shrubbery dotting the desertscape, No.1225 Chainlink is unnervingly imposing yet gracefully sensuous. Begum smartly diffuses the material’s divisive connotations through rhyming geometric architecture.

Desert X 2023 installation view, Rana Begum, No. 1225 Chainlink, photo by Lance Gerber, courtesy the artist and Desert X. Throughout, Desert X 2023 centers the significance of water to desertscapes, and three key installations create instruments reflecting the physicality of water cycles and climate change in drastically different ways. Salt, in turn, features heavily as a counterpart to water and a marker of its dearth. New York–based artist Torkwase Dyson’s Liquid A Place—the southernmost installation located in Palm Desert—is a large-scale abstract sculpture taking an utterly unique and meditative form of a gigantic, matte-black arch with a womb-like cutout. It invites viewers (as our bodies are predominantly water) to be a part of the history of water in this space as we travel through and over the piece via an implanted staircase. At the northwest corner of Desert Hot Springs, a towering telegraph pole submerged in coarse salt emits sonorous “prayers” from trumpet-shaped loudspeakers flowering from its top. Created by the London- and Delhi-based duo Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser, collectively known as Hylozoic/Desires, the multimedia Namak Nazar broadcasts curious echoes and tales into the vast barren landscape, a humorous nod to the proliferation of conspiracy theories borne out of the desert.

Finally, The Smallest Sea with the Largest Heart by Lauren Bon and Metabolic Studio is a mesh steel sculpture in the form a life-sized blue whale heart that hangs suspended in a pool of water from the Salton Sea. But rather than serve as portent of climate disaster, the sculpture metabolizes the shallow saline pond into clean energy and water, reminding us that the desert we stand in was once a sea and fueling the potential for new life over the run of the exhibition.

Just off by the I-10 intersects with a cross-continental freight rail line lies LA-based artist Matt Johnson’s epic Sleeping Figure. The work comprises 12 shipping containers propped precipitously in a humanoid form lounging laconically at the base of a snow-capped mountain range, replete with a painted sleepy smile. Sited within eyeshot of the cars roaring down the freeway toward the Port of Los Angeles, the colossal sculpture speaks aptly to the fragility and inescapability of the global economy and supply chain. Just as I was about to veer onto the I-10 West ramp, a freight train towing countless dozens of shipping containers identical to the ones making up Johnson’s sculpture thundered through the background of Sleeping Figure and into the receding horizon. I paused to watch before following suit in my car, feeling utterly transformed by my day in the desert and ready to chase the setting sun back to Los Angeles.

-

Commerce and Culture

Andy Freeberg’s Cheekily Captured Art-World InequalitiesEven when photographers are most concerned with mirroring reality, they are still haunted by tacit imperatives of taste and conscience.

—Susan Sontag, “On Photography”Photographer Andy Freeberg has become something of an inadvertent cultural sociologist. Born in New York City and currently residing in Northern California, he began his professional career as a photojournalist working for publications such as Rolling Stone, Time, The Village Voice and Fortune, photographing the likes of Patti Smith, the Rolling Stones, Miles Davis, Liberace and many political figures. In 2007, he shifted his lens to capture the more circumscribed realm of art-world environs—it was something of a hybrid move to fine-art documentarian.

“When I began doing the color art-world photographs, I was looking at Bernd and Hilla Becher’s influence on Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, and Candida Hofer. I liked the German typology idea but wanted to add a humanistic touch and some American humor to that style,” said Freeberg at his San Francisco opening last March,

In the 2007 series, “Sentry,” Freeberg turned his attention to New York’s Chelsea commercial galleries: those white-walled sanctum sanctorums with their often intimidating Modernist interiors. The formal, nearly identical images depict tableaux of gallery staff seated behind imperious desks that obfuscate their identities. These are a different species of gatekeepers. Cheim and Read is one of several pictures in this mordant series of officious yet emotionally inert scenes.

Freeberg’s 2008 series, “Guardians,” is a complete visual detour. Here he captures Russian babushkas who, for a small government stipend, sit beside historic paintings at Moscow’s State Museums. The saturated, operatic images cast the sitters as willing protectors of a grand cultural chronicle. Michelangelo’s Moses and the Dying Slave, Pushkin Museum (2009), pictures an imperious woman, arms crossed, guarding her charge with implacable resolve.

Tiburon House artist: Edite Grinberga, 2018. Courtesy of the artist. In a contrasting juxtaposition, his next series, “Art Fare” (2009) captures the art consiglieri at work—fully exposed, lobbying and selling pricey art at a public trade show. To most of the public, it’s an obtuse and murky place, surrounded by the ambiguities of elitism, negotiation and commerce. Freeberg explains, “Gallery owners and their staff are usually hidden behind large entry desks and closed office doors. But at the major art fairs I’ve visited, like New York’s Armory Show and Art Basel in Miami and Switzerland, they’re in plain view in their booths. As if on stage, you can see art dealers meeting with collectors, selling and negotiating, talking on cell phones, working on laptops. I found the lighting, costumes and set design excellent for photographing these living dioramas, where the art world plays itself.” One photograph, Sean Kelly, Art Basel Miami Beach, 2010 artist: Kehinde Wiley depicts Wiley’s arresting work foregrounded by enervated dealers—the art business can be a bit of a waiting game.

Initiated in 2017, Freeberg’s most recent and somewhat cheeky series, “Advisor,” was recently on view at San Francisco’s Jack Fischer Gallery. Freeberg tracked and photographed an art advisory group whose raison d’etre is satisfying the aesthetic requirements of the region’s budding tech nouveau riche. The advisors are called in to source, install and sell artworks on needy walls of the Bay Area’s contemporary palazzos—call it turn-key cultural services. But what, exactly, is a so-called art advisor? As it turns out, they have their own rather homogeneous membership association (the Association of Professional Art Advisors), which, according to their website, is dedicated to “emphasizing integrity, connoisseurship and education as the foundations of professional practice.”There’s more, but you get the picture; within that definition, there are myriad business-model permutations. (Disclosure: I do art advising on occasion.)

Freeberg attempts to maintain a dispassionate distance from this exclusive cohort, but it’s difficult for a viewer not to draw voyeuristic narratives from the images. Russian Hill, 2017 artist: Joseph Adolphe captures an art advisor at work, the young woman lugging a oversized painting of a bull into an elite hillside dwelling. Qualitative considerations of the chosen painting aside, the image seems a quintessential marker of the irrational financial exuberance that permeated the Bay Area economy, whose balloon was recently punctured further by a major bank failure.

Cheim & Read, 2007, from the series Sentry. Courtesy of the artist. Freeberg doesn’t pose or “style” these scenes, yet Napa Pool, 2017 artist: Benjamin Anderson reads as surreal set-piece, with an advisor hauling a painting in the background while a youth languidly peruses on a technological device at poolside—an aloof yet illuminating domestic scene. Los Gatos Living Room, 2017 artist: Kim Simonson pictures the Finnish artist’s striking moss-green sculptures, plopped incongruously on the floor, awaiting the works’ final domestic placement.

The images are not as straightforward as they might seem, with the advisors as de-facto gatekeepers and attendant aides-de-camp to a niche demographic. But the picture that most jarringly captures this pecuniary arrangement is Tiburon House, 2018 artist: Edite Grinberga. In the foreground, a young Latino gardener is mowing a pristine lawn while the art advisor dutifully handles a painting in the background. It’s a somewhat disquieting mise en scène that confronts the socioeconomic rifts between client, advisor and gardener. In a state where wealth inequality is pervasive, the tableau is reminiscent of artist Jay Lynn Gomez’ paintings and public sculptural interventions of the “invisible,” largely Latino, labor force that tends to the bucolic gardens and homes of Beverly Hills. The purposeful and incisive color compositions bring the juxtapositions into stark relief—although the repeated tropes and scenes make for a numbing equivalence.

Freeberg’s photography wryly captures the confluence of money, art and the facility of convenience: the age-old reciprocity of commerce and culture, where the latter can scarcely survive without the former.

-

Unknown Landscapes

Jessica Taylor Bellamy Explores the Wetlands“Can you smell the earth exhaling? I love the smell of moisture coming out of the ground,” exclaims artist Jessica Taylor Bellamy, inhaling the sweetness after the drizzling rain as we embark on our Sunday afternoon hike through the wetlands of South Los Angeles. As we descend the muddy hillside draped in bright yellow wildflowers, we share a moment of childhood nostalgia, recalling wild mustard flowers that flourished vividly in our memory. Looking down at the soles of my sneakers, already caked with dirt, I feel a sense of wonder, enchanted by the green, dewy world before me, as if I were 10 years old, my clammy hand nestled tightly in the palm of a friend.

Bellamy and I met as graduate students at USC in 2020. Our friendship blossomed around our shared interest in ecological theory, Mike Davis, Octavia Butler, and growing up in Southern California in the Y2K era. Our conversation about LA, art and ecology is ongoing and personal—it is an ever-evolving dialogue grounded in friendship and a mutual desire to care for the planet.

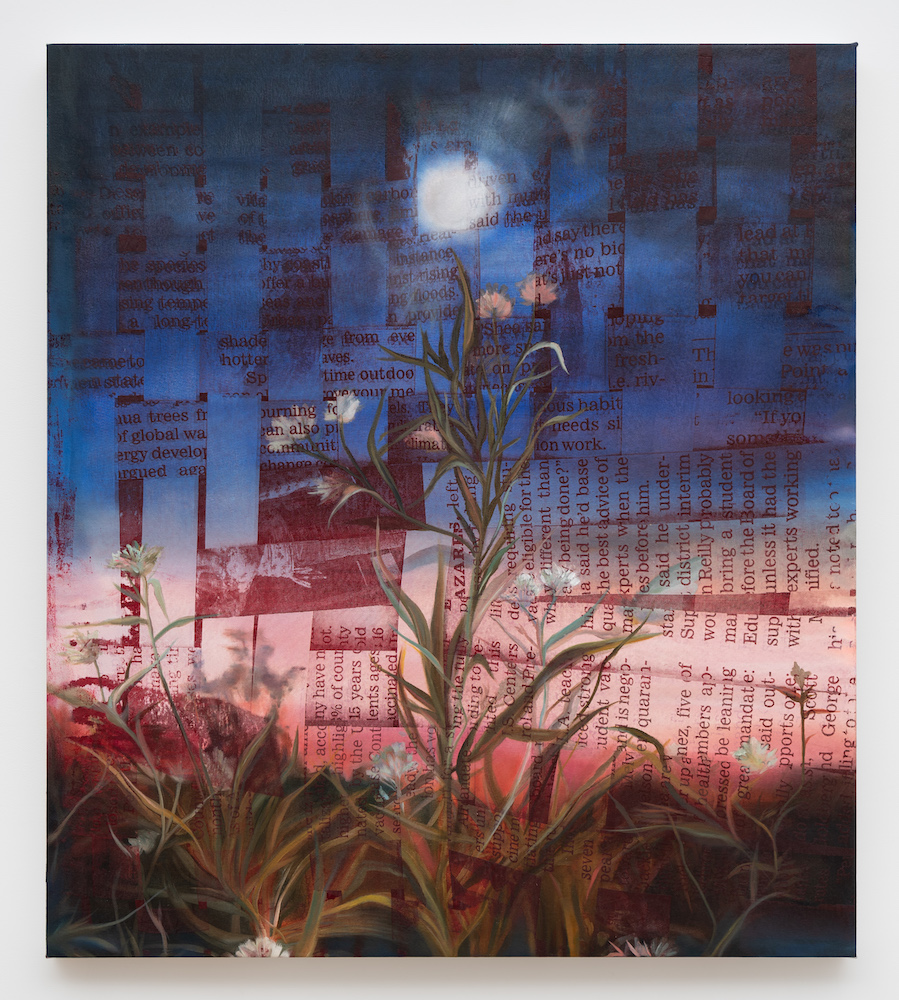

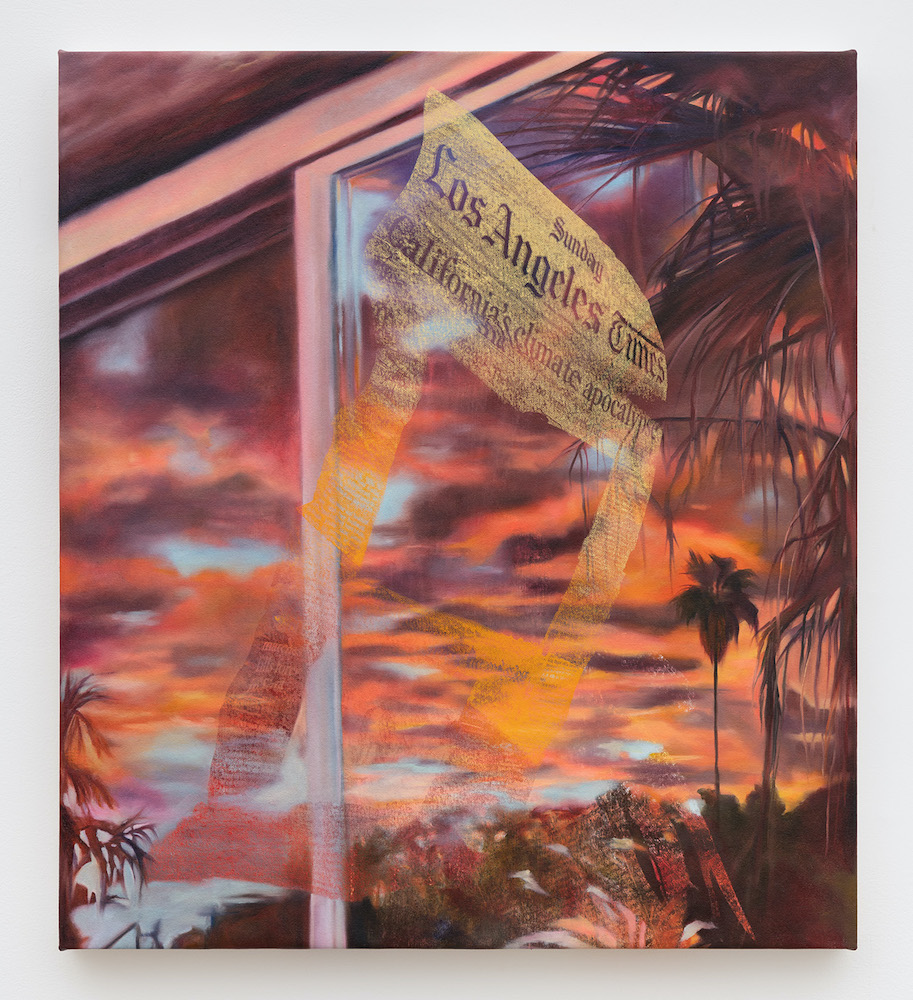

Guided by eco-phenomenology, Bellamy’s work is informed by the city’s shifting environment and ecological entanglements, her experiences, observations and familial history. The artist’s prolific practice spans painting, screen printing, film, sculpture and installation, all of which incorporate observational and scientific research, found images and a well of archival materials she has developed throughout the years. While her approach often involves figures and data, it is also experimental and poetic. Many of her paintings incorporate found text from popular media sources such as the Los Angeles Times hand-screenprinted onto her paintings, resulting in juxtapositions that expose tensions embedded in the city. Myths of sunshine and noir collide in her beautiful, almost sublime renderings of the California landscape overlaid with headlines about social and environmental devastation—situating her practice in a specific place and time.

Jessica Taylor Bellamy, Proving Ground, 2023. Our conversation took place in and around the Ballona Wetlands Ecological Reserve, located just down the street from Bellamy’s home in Playa del Rey and a short distance from where I grew up in Palos Verdes. With hundreds of acres of salt and freshwater marsh, the park’s meandering terrain feels both contrived and unruly. It exists in a constant state of construction and repair in coordination with the Ballona Wetlands Restoration Project (BWRP), which aims to reconnect the land and the sea, allowing fresh and salt waters to flow and support a healthy ecosystem.

“People don’t realize there is actually nature in Los Angeles; you just have to know where to go,” Bellamy states as she points toward a thorny vine of wild strawberries crawling along the trail’s warped wooden fence. The sound of bugs and critters trilling around us resembles a pulse—life and earth percolating with rambunctious vitality. White egrets graze elegantly at the water’s edge, seemingly unfazed by the flight path overhead or the sound of traffic from surrounding intersections. It’s as if the egrets decided to tune out the buzz of the city. This entanglement of life and death (human and nonhuman) and environment (built and natural) exemplifies the collaborative ecological thinking at the heart of Bellamy’s practice.

Bellamy points up at two hawks soaring across the murky skyline. She always seems to know when a hawk is nearby. Various animals and plant life operate like symbols in her practice, taking on particular meanings relating to the artist’s identity and environment. Hawks can be found throughout the artist’s work and tell a story about her father, who immigrated to California from Cuba in the late 1960s and eventually settled in Inglewood, where he learned to train red-tailed hawks to catch mice and other small critters. Bellamy has become attuned to the strange spaces where nature and culture interact.

The mud beneath our feet grows stickier as we travel deeper into the wetlands, the dirt telling our bodies to slow down and look. “Los Angeles is an ongoing construction site,” says Bellamy, as we stumble upon a fence that appears to be sinking into the muddy water. Crooked and nearly half-submerged, the fence looks silly and trite, like an artificial boundary for the mouth of the marsh to swallow, for nature to devour. This image recalls the many variations of screens and portals that appear in Bellamy’s work—found and imaginary, natural and artificial. A recent painting titled Floods in a Desert (included in the artist’s inaugural exhibition with Anat Ebgi gallery) depicts a window that is warped by the ghostly impression of a Washingtona robusta leaf (Mexican fan palm), further abstracted by layers of cracks and fragments that resemble broken glass. Rays of kaleidoscopic light seep between the layers of reality, refracting and deflecting to further distort any sense of perspective. This underlying menacing beauty evokes the paradoxical feeling of living in Los Angeles. Bellamy exposes the tensions built into the city and considers how they are amplified by the clash of fantasies, mythologies and realities.

Jessica Taylor Bellamy, Ignorance and Nothing More, 2023. “We’re almost near the crazy-ass birds!” Bellamy announces with an eager giddiness, hurling her finger into the air to guide my eyes across the water toward a pair of resident Canadian geese that stand charmingly side by side at the edge of the marshland. She explains that they are grounded in the wetlands due to the disruption of their migration patterns, like nonhuman climate refugees. These geese make me think of agency (and oppression) from a multi-species perspective.

Bellamy reminds me that the LA wetlands undergo “rewilding” every year in an effort to remove invasive species that could potentially disrupt the ecosystem. The following stream of questions arises: What makes an invasive species invasive? Do invasive plants and critters have agency? Or is their invasiveness just a mode of survival? A reaction to their forced displacement? Should we consider ourselves (humankind) an invasive species? After all, aren’t we the ones choking the climate to death in the name of “progress”? Agency shifts and falters with every collision and collaboration or, in Karen Barad’s words, “Existence is not an isolated affair.”

Bellamy tells both macroscopic and microscopic stories about agency and oppression, collected and constructed from her lived experience and intimate observations. She helps instruct us on how we might feel the ground exhale.

-

Of Murals and Mullahs

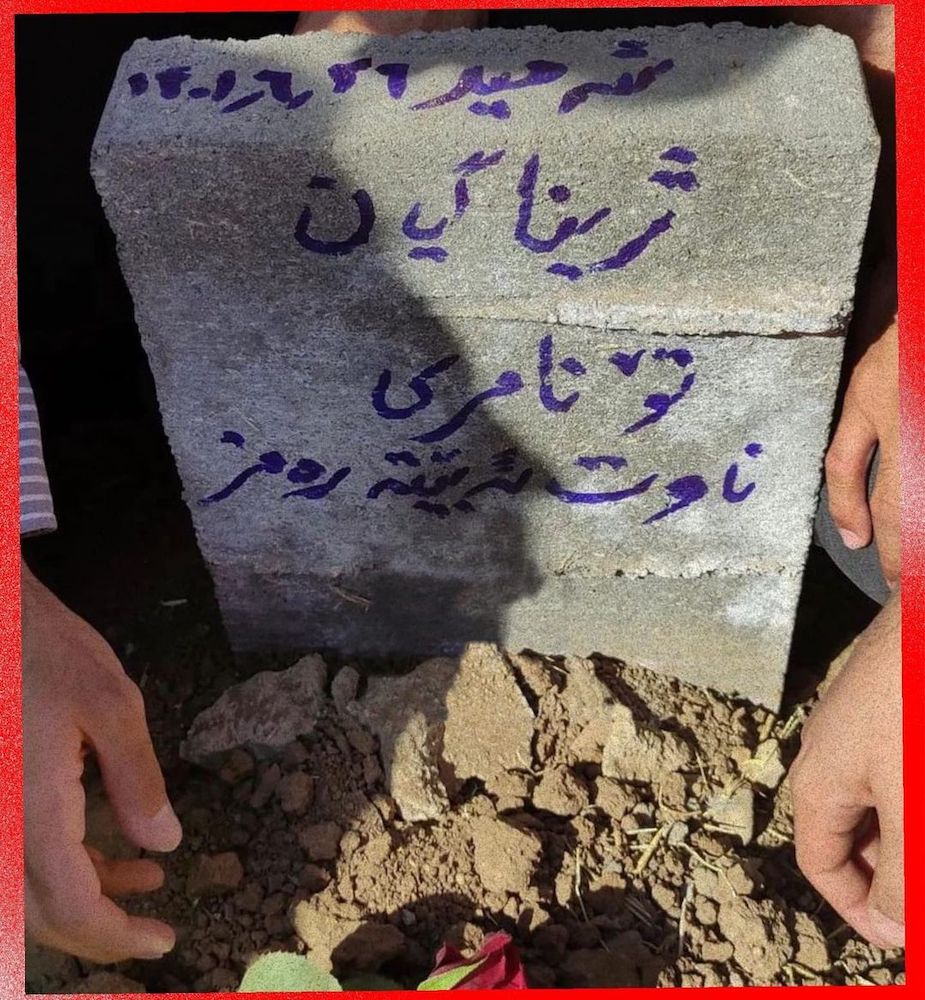

The Revolutionary Graffiti of IranIt began with marker on concrete: “Dear Zhina, you will not die. Your name will be a symbol.”

Zhina was the Kurdish name of Mahsa Amini. On September 13, 2022, the 22-year-old was arrested by Iran’s “morality police” for wearing her headscarf too loosely. While in custody, she was murdered. Mahsa’s grandfather wrote those words on her gravestone.

#MahsaAmini did become a rallying cry, igniting worldwide protests on behalf of “Woman. Life. Freedom”—“Zan. Zendegi. Azadi.” Protestors in Iran took to the streets—and continue to do so—despite lethal crackdowns, sexual assaults and poisonings. Women removed their hijabs and cut their hair. At the same time word of #MahsaAmini and #IranRevolution spread on social media and the protests expanded. Iranians expressed their exasperation over the repressive regime of President Ebrahim Raisi and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei with its economic woes, corruption, floods, droughts and ban on dogs. The litany of woes was captured in Shervin Hajipour’s Grammy Award-winning protest anthem “Baraye” (For The Sake Of).

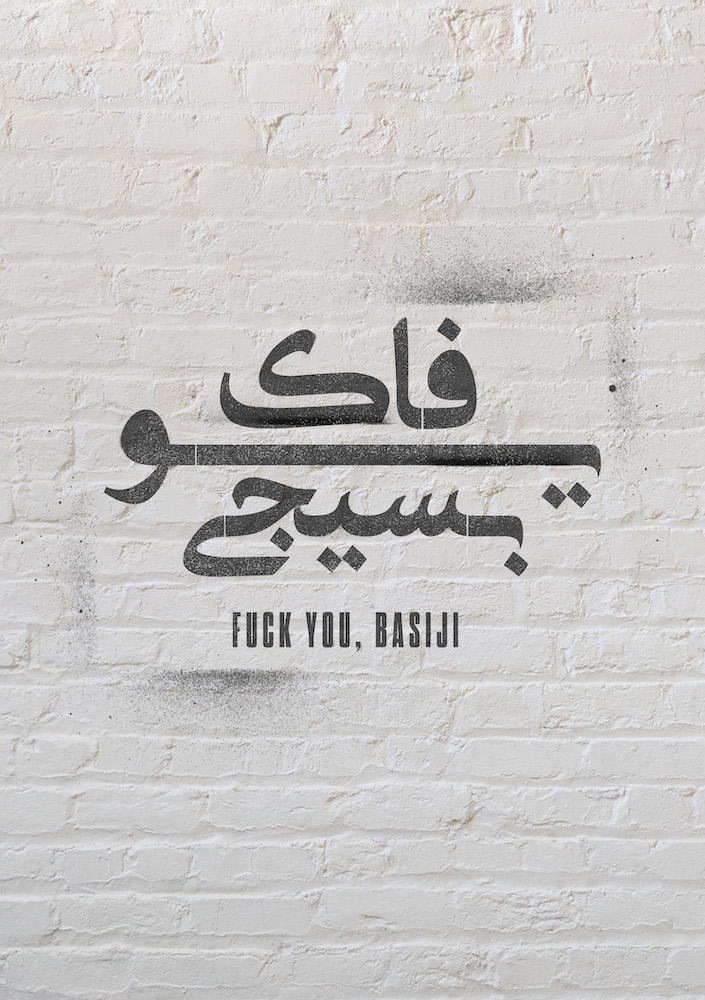

In the early days of the revolution—just as they had with previous uprisings—the Islamic Republic shut off the country’s internet, and the protests continued with spray-paint on bricks: “Resistance is life.” But the Islamic Republic was ready with buffers and white paint, because this is a regime that understands the power of words and images on a wall.

Public mural in Tehran defaced with paint. Photographer’s name withheld for their protection. Following Iran’s 1979 revolution, the Islamic Republic embarked on a propaganda campaign of polluting Tehran’s visual space with large-scale murals on public and private buildings. In the early 1980s, murals featured the supreme leader of the revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. During the Iran–Iraq War, depictions of “martyrs” killed in the “Imposed War” headlined Tehran’s multi-story buildings, rendered in bright primary colors and Islamic green. Iranian-American anthropologist Roxanne Varzi said, “It was the war that ultimately defined the Islamic republic as an image machine.”

Regime-sanctioned muralists have kept the machine running. In 2020, a US drone assassinated Iranian General Qasem Soleimani for his key role in coordinating bombings and other hostile actions. On January 2, 2023—the third anniversary of his death—the country’s largest mural was raised above Enqelab Square in central Tehran: a 15,000-square-foot billboard of Soleimani flanked by other “martyrs of the devotees of the nation.”

Hijabs and walls are synecdoches for the regime. The Islamic Republic controls what is seen and covered; they regulate the heads of Iranian bodies and buildings. No wonder, then, that some of the first acts of revolution were Iranian citizens removing hijabs and knocking the turbans off of mullahs. And perhaps it’s not surprising that numerous Instagram photos of graffitied walls are accompanied by women posing without hijabs and, sometimes, with lifted shirts.

Mahsa Amini’s grave. Photographer’s name withheld for their protection. The regime had failed to recognize the tacit refinement of another image machine. These revolutionaries had grown up beneath a sky overcast with propaganda murals; and on phones and computers inside these decorated buildings, they, too, had mastered the power of words and images.

In response to the regime’s rapid erasure of graffiti, protesters began dating their messages: “Death to Khameni – October 16th.” When Iranian authorities whited out “Woman. Life. Freedom.” on a bank’s door, Iranian citizens painted over that with: “Blood cannot be cleaned with anything.” In honor of Mahsa Amini, and all she symbolized, Iranians invaded roofs and poured paint on those state-sanctioned murals, smearing Khameni with dripping blood-red color.

Mahsa and her generation grew up in the literal shadow of violent and repressive men. They are now coming into the light, removing their hijabs, hanging them from Tehran billboards, and reclaiming the country—and walls—for themselves.

-

“Britt Ransom: Arise and Seek”

at Pitzer College Art GalleriesWhen stepping into Britt Ransom’s solo exhibition, you face an archway. This reproduction, created with 3D scans, prints and a CNC machine, revives a signature piece of the Tawawa Chimney Corner house in Wilberforce, Ohio. Today, only the arch’s stone pillars remain, but Ransom dug into her family archives to find a photograph suitable for reference. In “Arise and Seek,” Ransom amplifies her ancestors’ role in the civil rights movement, commemorating their activism with architectural forms, sculptures, photographs and ephemera.

On the second floor of the gallery, a large timeline stretches across the mezzanine, thoroughly detailing the legacies of Ransom’s great-great–grandparents, Bishop Reverdy C. Ransom and Emma Ransom, who are central to the exhibition. In the early 20th century, they were instrumental in advancing the civil rights movement; Reverdy, with famous activists such as W.E.B. Du Bois, co-founded the Niagara Movement, the precursor to the NAACP. Emma championed suffrage for Black women. The two spent many years residing in the Tawawa Chimney Corner house, where they held dialogues with prominent figures such as Du Bois, Ida B. Wells, Jane Addams and President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In 2020, the house was added to the National Register of Historic Places, despite its deteriorated condition. The paint on its white farmhouse siding is chipped away, the wood is rotting and windows are boarded up. Ransom, with the help of her relatives, has acquired funding so they can repair the exterior. In the meantime, she can prototype its restoration and transform it into contemporary art.

Ransom utilizes digital fabrication techniques like laser cutting, photogrammetry, 3D modeling and printing, and computer-controlled milling to make detailed reproductions of living organisms. “Arise and Seek” is her first foray into building monuments, and she worked collaboratively with makerspaces, historians and archives across the country. They helped Ransom reproduce the Tawawa Chimney Corner house arch with sturdy recycled foam and employed digital-surface design methods to reconstruct the house’s old wallpaper, which blankets one wall. A column was sculpted from 3D prints and resin casts of Ransom’s hand-grip laser-cut steel plaques, which memorialize Reverdy’s speeches.

Ransom was not the first family member to test cutting-edge machines. An archival print, Emma Ransom Multigraph (all works 2022), shows many reflections of Emma’s body in a carousel of mirrors. Taken in the 1890s, the multigraph was a unique composition that embraced emerging technology, the camera and lens. Ransom repeats this technique multiple times. With Layering Sites, acrylic scale models of the Tawawa Chimney Corner house and abolitionist John Brown’s fort in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, are made infinite. In one corner, a section from the column Can a Nation So Soon Forget?—held by one of Ransom’s resin hands—blossoms five times in mirrored reflections. Both pieces fold the viewers into the work, urging them to consider their place in civil rights history.

Much of the show mediates upon whose stories are told in monuments, and Ransom tries to fit her own family’s history into the gaps left by federal preservation. She gives prominence to Brown, who attempted to spark a slave rebellion in the pre–Civil War era. He was a hero to many civil rights leaders, and Reverdy channeled Brown’s tenacity in his speech “The Spirit of John Brown,” which he delivered at the second meeting of the Niagara Movement.

There are many monuments dedicated to Brown across the country, including the fort in Harpers Ferry, which are marked by institutional bronze plaques. One of these plaques, which Ransom has recreated with the work John Brown Fort Site Reconstruction, was funded by the NAACP. Ransom mounts a steel rod to connect this plaque to another replica, Tawawa Chimney Corner Plaque Reconstruction, to emphasize the connection between her ancestors and Brown’s fame. It’s difficult to measure just one person’s impact on any historical movement, but Ransom’s pieces suggest that Reverdy and Emma’s legacies should be treated with equal importance.

Installation views of “Britt Ransom: Arise and Seek,” January 28—March 25, 2023, at Pitzer College Art Galleries. Photos by Christopher Wormald. Another set of pieces, Arise and Seek (Series of 2), takes excerpts from two of Reverdy’s speeches made in Boston, A Philippic on the Atlanta Riot (1906) and On John Greenleaf Whittier, Plea for Equality, Centennial Oration (1907), and transcribes them on bas-relief to make them appear as historic plaques. Unlike many of the reproductions in the show, these monuments do not actually exist outside of the gallery, but Ransom has imitated the aesthetic to anchor Reverdy’s place in history. Both are adorned with Ransom’s resin hands. She literally carries Reverdy’s words into the present, fulfilling her responsibility of sharing her family’s story.

Even when people like Reverdy and Emma have been formally documented, their stories are still at a high risk of being forgotten. Many will never have their stories told at all. This is exemplified in another wallpaper Ransom created, Harpers Ferry (Wallpaper), which utilizes an image of those who gathered for the second Niagara Movement in 1906. This image is also adhered to informational markers at Harpers Ferry National Park. It shows 46 men, but only a few of their names are recorded on the monuments. Some men stick their head out of open windows, unable to fit into frame, and one man’s body, seated at the edge of his row, has been cut in half by the camera, making him anonymous. Ransom’s wallpaper uses a mirroring technique to make the photo infinitely expand, and it incidentally reflects this attendant’s half-captured profile, reconstructing his face in a distorted format. While his name remains unknown, Ransom has restored his place in the movement.

To be represented in history takes a lot of money and influence. Ransom’s National Parks Service grant to restore the Tawawa Chimney Corner house will prolong its life but won’t be enough to save it permanently. Family members need to find more support before they can realize their dream of turning the house into a museum and cultural center with a permanent library, an art collection by significant Black artists, and a community meeting space.

Before the home can be fully renovated, Ransom must recapture the public eye, commemorating Reverdy’s and Emma’s dedication to Black equality and suffrage. “Arise and Seek” is just another chapter in a long story that will continue through art, monuments, and activism.

Installation views of “Britt Ransom: Arise and Seek,” January 28—March 25, 2023, at Pitzer College Art Galleries. Photos by Christopher Wormald. -

ART BRIEF

Hermès Bags a Win Against ArtistThe Hermès Birkin handbag is the stuff of legend. Named for actress Jane Birkin, each bag is hand-tooled in the finest leather or crocodile. The bags are highly sought out by the nouveau riche. Customers for new releases are placed on a waiting list and there is a brisk online resale market with some vintage bags priced in six figures. Hermès is known for vigorous defense of its trademark, but it was still somewhat of a surprise when the fashion house sued a little-known digital artist, Mason Rothschild, for trademark infringement for selling what he calls “MetaBirkins” as NFTs.

NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, are entries on blockchain ledgers to indicate ownership of the first digital file of an artwork. In 2021, Rothschild created a digital series of 100 MetaBirkins adorned in various multicolored faux-fur combinations priced at $450 each. The artist registered the “MetaBirkins” as a trademark. Hermès didn’t get the joke and sued Rothschild in New York federal court, charging him with infringement, trademark dilution and cyber-squatting (registering a mark that overlaps with a pre-existing one).

What made the case so important was that it was one of the first to determine whether NFTs are art protected by the First Amendment or whether they are simply commercial products subject to trademark law. Rothschild said that he was spoofing “consumerism.” He has a point—just how a well-heeled buyer of a Birkin would be confused by a fictitious “MetaBirkin” is hard to imagine.

Hermès’ complaint stated: “Although a digital image connected to an NFT may reflect some artistic creativity… the title of “artist” does not confer a license to use an equivalent to the famous Birkin trademark in a manner calculated to mislead consumers and undermine the ability of that mark to identify Hermès as the unique source of goods sold under the Birkin mark.”

In the February trial, the jury found Rothschild liable for trademark infringement and dilution, awarding Hermès $110,000 plus an additional $23,000 for cyber-squatting. More importantly, the jury concluded that NFTs are not art, and therefore do not have First Amendment protection. Rothschild’s lawyers had argued emphatically that NFTs should be considered art.

In March, 2021, this column covered the spectacular sale by Beeple, a well-established digital artist, of his NFT Everydays: The First 5,000 Days for $69 million in cryptocurrency at Christie’s. In that column I concluded that NFTs are not art—they are entries on the blockchain ledgers—even though the underlying digital file can be considered art. NFTs convey no intellectual property rights to the buyer such as copyright or trademark. In addition, as we have seen in the Hermès case, NFTS may expose the digital artist to trademark infringement.

The buyer of The First 5,000 Days was a crypto “whale” who goes by the name of Metakovan—a promoter of Ethereum who went on to sell fractional shares in the Beeple NFT to buyers who paid in that currency. The Beeple sale turbocharged NFT sales of such mundane items as NFT photos of Kate Moss sleeping, which went for six figures each. NFTs had the misfortune of being tethered to crypto, so in the wake of last year’s crypto crash the volume of NFT sales declined 97% according to The New York Times.

The judge in the Hermès case excluded from evidence an expert report prepared by Times art critic Blake Gopnik that compared Rothschild’s works to the works of Andy Warhol incorporating commercial imagery, such as paintings of Campbell’s soup cans. Gopnik wrote an op-ed in the Times, he called Rothschild’s artwork a campy riff on Birkin bags; he concluded that, as a parody, the works should be protected by the First Amendment’s free speech clause. While Gopnik is correct about Warhol (whose work pre-dated the NFT era), he completely ignored the issue of whether an NFT is art. Gopnik’s expert opinion might not have mattered to the jury anyway.

The jury made a decision that NFTs are commercial products and thus subject to trademark infringement. Rothschild says he will appeal the verdict. The appellate ruling will be closely watched. The trial verdict has dealt a major blow to the already battered NFT market.

-

OFF THE WALL

Stickering it to the ManGraffiti has always been a declaration of independence and individuality; it’s the big I AM, designed to disrupt everyone else. Large Graf throw-ups, or wall pieces, may show off the artist’s skill and message, but they are also considered vandalism—incurring maximum reaction from the police. “Fellons,” specific street painters considered the most infamous, face incarceration and steep fines if caught, so they often resort to stickering instead. Stickering, also known as sticker-bombing, slap-tagging and sticker-slapping, is the act of attaching stickers to surfaces where they will get the most attention. Stickers are considered as much of a civic nuisance as murals but result in virtually no prosecutions. San Francisco stickerer Justin Kerson explained in an email, “Stickering falls inside a gray area when the defense is worded right. If a cop asks, I tell them it’s a temporary, removable political campaign protected by an amendment. And it’s not just the cops that go easy on stickers, I’m buddies with so many different Graf crews because I don’t paint and my stickering is not a threat to them.”

Another advantage of stickers is that, if slapped in the right place, they remain in situ far longer than a wall that took hours to paint. Plus, a sticker may burn on a sign and be seen by just as many people as a large piece. Most importantly—although wall murals may be the most impressive form of Graf—they require an audience that comes to them. Stickers are free of this constraint: When applied to a kid’s water bottle, guitar or laptop, they get mobile city-wide exposure. This populist approach can result in a tight camaraderie. Kerson maintained, “If a homie asks for a stack heading out of town, you give it to them. So, I get pics of stickers I never put up all the time. I figure I have over 100,000 stickers running across the world; Earth is small these days.”

This earthly diminution can be attributed to the web and a youth culture that embraces instantaneous global communication. More importantly, it has resulted in an informal international sticker exchange. Stickers are sent from one country to another, and the satisfaction Kerson gets from seeing his stickers in Africa is equal to a foreign stickerer’s thrill at receiving photos of theirs in California. Even so, there are people who bypass that reciprocity, said Kerson. “You can pay other people to wheatpaste or put up your stickers, but it’s still your idea.”

Stickers can represent that a person has gone there, to another place; but to the street-initiated, they also signify a person has been here, in the same place. Sticker-bombing, like tagging, is a quick way to claim territory, but it’s an equally efficient way to invade. In the end, Kerson admitted, “It’s still the ego, dog-pee-on-everything game.”

-

THE DIGITAL

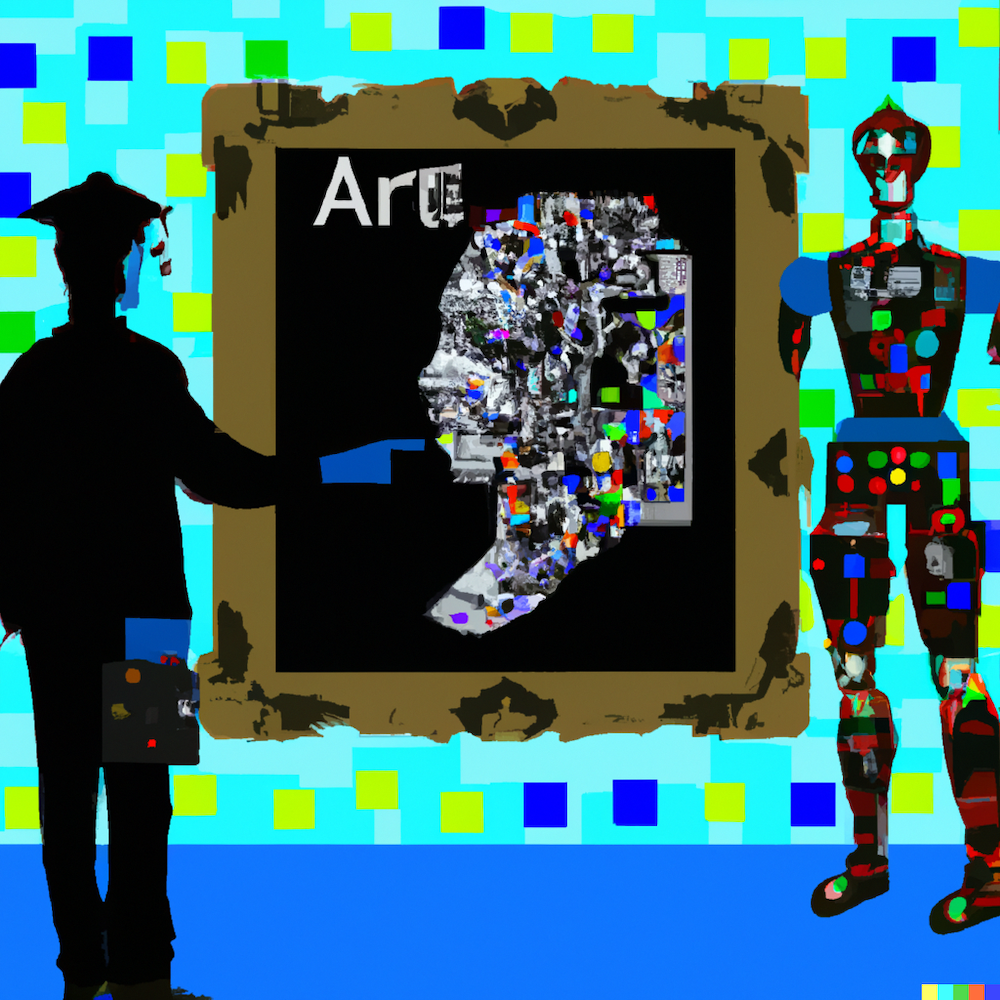

Worshiping at the Altar of Algorithmic CreativityAs I sit and stare out the window and contemplate human existence, my upcoming day and this overdue column, AI is endlessly cycling—solving problems, making systems more efficient, creating previously unseen connections, secretly planning world dominance and on top of it all, finding time to make fine art!

Yes, art imitates life, and the machines are winning even within the impenetrable blue-chip art world. AI-generated imagery has unshackled itself from Instagram influencers and is currently garnishing the walls of Gagosian Madison Avenue with a new exhibition which was created by the AI-image generating program DALL-E. Bennett Miller, noted film director and AI documentarian, is credited as producing the exhibition, but the topic of the artist is a murky one.

Let’s pit one AI program against another. In this AI battle royal, I will use ChatGPT—a second AI program created by DALL-E parent company Open AI—to critically evaluate and explore its “thoughts” on the implications of algorithmic art. ChatGPT, unlike DALL-E, does not create images, but rather produces text and defines itself as a “conversational dialogue model, a chatting robot, trained by AI and machine learning.”

With ChatGPT free to the public, it is currently used for everything from the most benign to grandiose human ideas—influencers ask for ways to gain more followers, businesses use it to streamline marketing plans, governments ask it to review tactical negotiation strategy. The text for the Gagosian exhibition was written by author Benjamin Labatut partially using ChatGPT.

On to the experiment/AI battle: I have used the following prompt to have ChatGPT produce the following thoughts about AI in major galleries: “Write 250 words exploring the implications of AI art at major art galleries in the style of Artillery columnist Seth Hawkins.”

The rise of AI-generated art has become a hot topic in the art world, with major galleries exhibiting works created by machines. Some critics have dismissed it as gimmicky, but the implications of AI art are profound. With algorithms capable of creating art that is indistinguishable from that made by humans, we are forced to confront questions about what it means to be creative, and what the role of the artist is in the digital age.

The use of algorithms and programming in art creation raises questions about authorship and originality. Who is the true creator of the piece: the programmer or the machine? Moreover, the ability of AI to generate infinite variations of the same work challenges the uniqueness and authenticity of art.

In some ways, AI-generated art contradicts the traditional notion of the artist as a solitary genius. The algorithms that create these works are the product of collaboration between human programmers and machines, blurring the line between creator and created. At the same time, the algorithms are capable of producing art that is completely original and unpredictable—suggesting that there is still a place for individual creativity in the age of AI.

The rise of AI-generated art at major galleries is a worrying development for the art world—it threatens to strip art of its human touch and reduce it to a series of calculations. As we continue to grapple with this new technology, it is important to remember the value of human creativity and the unique experiences that only it can bring to the art world.

Since it seems I may have just been replaced by ChatGPT, I might as well do a final summation and finish with another quote by the genius algorithm.

As AI steamrolls forward—growing and learning by the day, never resting or taking time to contemplate—it is destined to create paradigms we never fathomed would exist in both life and art. Humanity is blind to whether we are barreling toward societal-changing advancement or more likely a Terminator-esque Judgment Day waiting around the next turn.

In the words of ChatGPT and the fitting style of Hunter S. Thompson, one last brief take on AI art:

AI art is a strange and bewildering creature, lurking in the shadows of the art world like some kind of digital ghost. It’s a technology that promises to revolutionize the way we create and consume art, but at what cost? Will we become slaves to our machine overlords, worshiping at the altar of algorithmic creativity?

-

BUNKER VISION

Chaos Access TVBefore the advent of online videos, the only way to take your moving images outside of the underground film and video art context was to get them on television. Chris Burden made commercials, and performance artists infiltrated The Gong Show, but the real hidden treasures found their way to cable access.

As a compromise for their monopolization, cable companies allowed anybody who wanted to make a show to have access to the local airwaves. MoMA recently screened a one-hour edit of one of the loopiest shows to ever grace New York television: Cash from Chaos (later known as Unicorns and Rainbows after the station started receiving complaints, and they had to pretend to be another show).

This show was the brainchild of Alex Bag and Patterson Beckwith. It screened in Manhattan late-night slots between 1994 and 1997. In a 2014 interview with MoCA, Bag explained her frustration with the hierarchy of “video art” and the art teachers who drew a hard line between high and low culture. She recounts a list of things that weren’t allowed by her video art instructor. In short: NO FUN. Video art was meant to be serious and high-minded. Performing a repetitious activity in denim was Art. Using costumes and references to popular culture were not.

It’s strange to look back on that era and realize how arbitrary those rules were. Another aspect to cable access as video art is that the people working in this medium couldn’t sit around and wait for virtuous inspiration to strike. Every single week there was a deadline to fill up the allotted time slot, which added urgency to the proceedings.

An interesting thing about doing a cable show was the air of legitimacy that it added to the players involved. In one episode, they scored an invitation to an event in Central Park, where BMW was promoting a tie-in with the latest James Bond film. After they filmed themselves taking the tabs of LSD that arrived in a collage mailed from Switzerland, they discovered that they had been invited to drive a BMW around the park “as fast as they can go.” There was a rather large police presence to keep the road clear, and knowing that the driver (filmed from the passenger seat) was frying on acid gave the viewer a sense of complicity in something genuinely transgressive.

One motif in these shows was to call product consumer hotlines to ask questions, which transcended the realm of prank calls by virtue of an earnest purpose. Another running motif consisted of wild interactions with actual VHS videotapes, which were struck with guitars, cooked in omelets and thrown into the street where cars ran over them.

The players became endlessly inventive as the need to fill their weekly half-hour loomed. In this bygone era, editing videotapes for mashups was achieved by wiring two video machines together, which, from the perspective of a time when telephones now include editing software, feels archaic and visceral.

Although the MoMA video compilation was only up for two weeks, it was great to see this chaos in a high-art context. You can catch bits of the show posted to YouTube, so it’s likely to have a long afterlife. Perhaps the endless new streaming services’ need for content will bring us a 21st-century version of cable access. Hope springs eternal.

-

CODE ORANGE

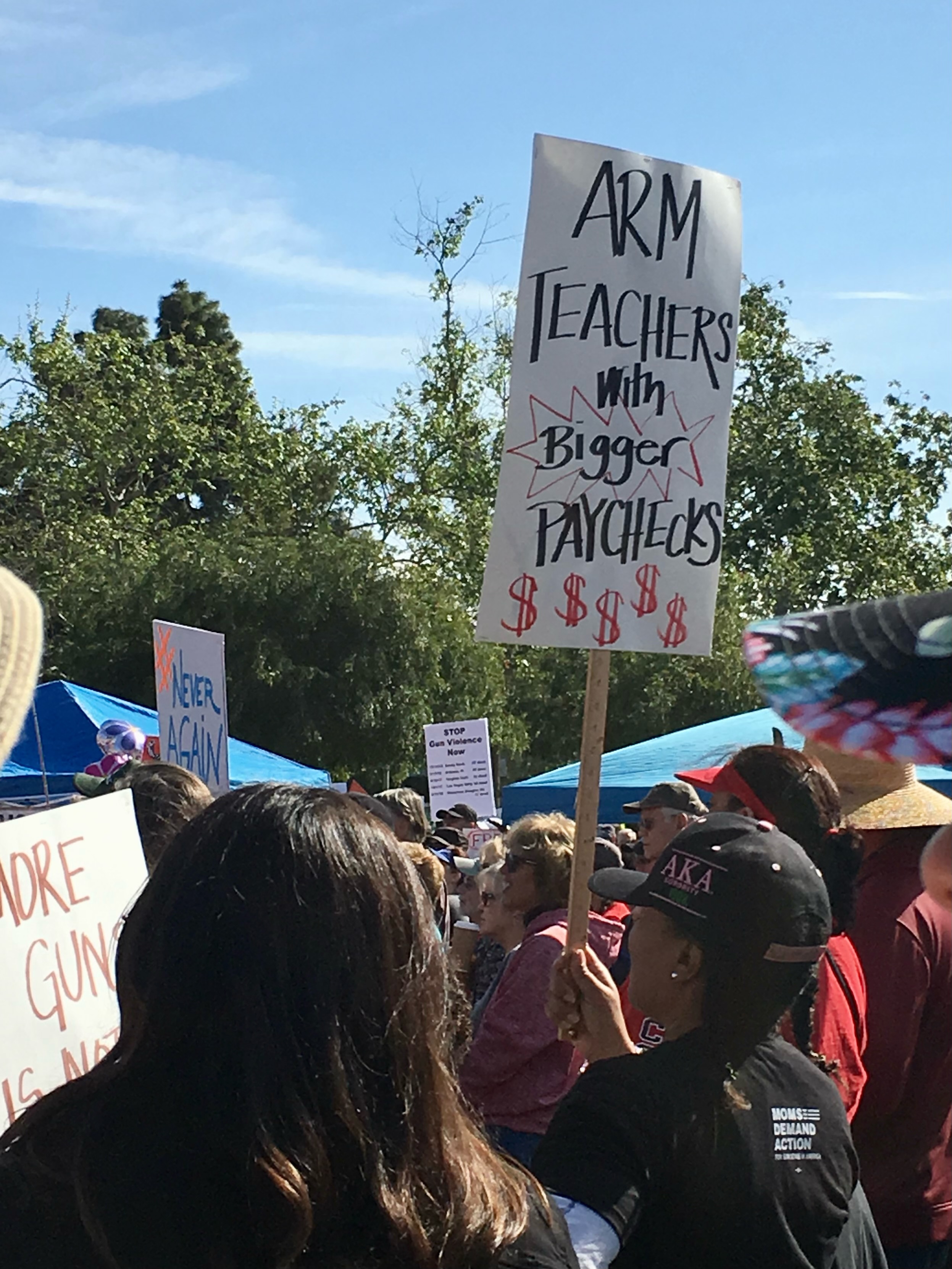

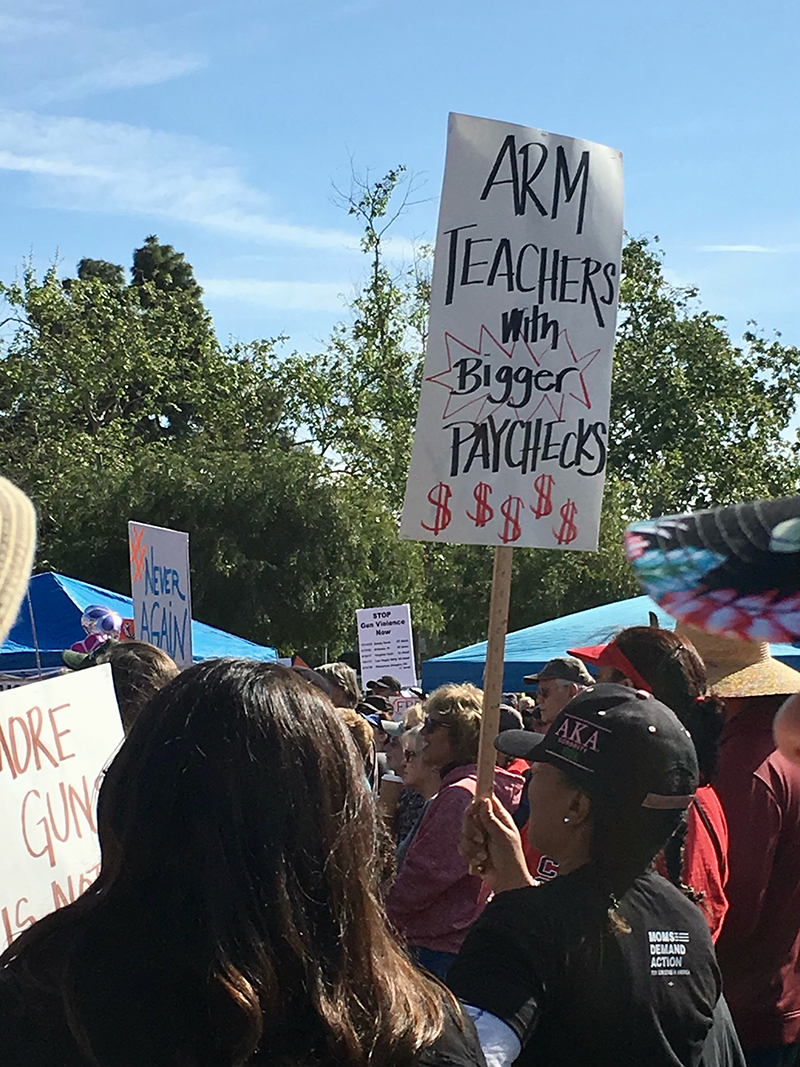

May/June 2023 Winner & FinalistsCongratulations to our winner, Maureen Vastardis, and our finalists, Maureen’s photo is seen above and first in our photo gallery in the May/June 2023 online edition of Artillery. The following photographs are the finalists. Please see the info below on how to enter for our July/August 2023 online-only photography column Code Orange.

Maureen Vastardis, Never Ending Story, March 2018, Long Beach, California; Digital Photograph Diane Cockerill, All Gender, April, 2023, San Pedro, California; Digital Photograph Richard Coal, Streets On Fire, 2023, Hollywood, California; Digital Photograph Anthony Ausgang, Everything’s Fucked, September 2022, North Hollywood, California; Digital Photograph Cecilia Arana, Topanga Market South Central, 2023, Los Angeles; Digital Photograph Gayle Nicholls-Ali, To Market to Market, September 2021, Altadena, California; Film Photograph Sheldon Polsky, Evolution, 2011, St Louis Zoo, Digital Photograph Precious Aiyeloja, Untitled, February 2023, Los Angeles, California; Film Photograph Lane Barden, Olive Tree Jan 9, 2023, L.A. State Historic Park, Los Angeles, California; Digital Photograph Brendan Lott, April 7, 2023 12:21am, Los Angeles, California; Digital Photograph CODE ORANGE is a web-based photography column and opportunity to have your work published in the magazine, curated by LA artist and photographer Laura London. Chosen entries will be published online in Artillery and finalists will appear online. CODE ORANGE is a documentary photography project and outlet for artists to express how they feel about the current state of the world.

Tumultuous times like ours have historically produced some of the most interesting, captivating, and timeless art; we hope to find and share similar works today. Images submitted should capture how our country and the world are affected by political, environmental change, social, personal, universal, identity issues. Photographs can be produced using a film or digital camera or smartphone. Black-and-white and or color images are accepted.

Ten photos are selected by London, one winner and nine finalists. The winner will receive a one-year subscription to Artillery. Their photo will appear on our homepage website for two months and winner and finalists will appear in our weekly Gallery Rounds newsletter, along with our Instagram post.

Good luck and we look forward to seeing your photographic submission!

DEADLINE for our July/August 2023 issue: June 24, 2023

Specifications for photo submissions:

• Only one photo per person

• FOR WEB: 72 dpi; 600 pixels wide. (hang onto your original large file in case you are selected for publication)

• Include: Artist Name, Title, Date, Place, and Medium (in that specific order)Label Image: First name, Last name,

Write the text for your image: First name, Last name, Title, Date, Location; Medium

• Email your photograph entry to lauralondon@artillerymag.com

-

ASK BABS

AI-generated Art (Again)Dear Babs,

Your last letter really pissed me off. You spent so much time talking about how great AI art is that you glossed over the more serious issues of copyright and intellectual property. What gives?

—Pissed in Pasadena

Dear Pissed,

I only got so many words for this column, and I had a lot to say, so cut me some slack. But you’re right that AI programs like DALL-E and Midjourney raise serious questions and potentially dangerous problems in relation to art. Let’s unpack this.

When it comes to hand-wringing about art, obviously we need to reconsider current laws and regulations concerning intellectual property rights. While it is not a crime to ask an AI to create an image of Joe Biden in the style of Yayoi Kusama and sell the image in all its dot-filled glory on an Etsy store, it does feel just plain wrong. One solution is that all of us start demanding that everyone using AI to create and sell work discloses the data sets, prompts and level of human-AI interaction involved in their process. However, this does not solve the issue of AI systems using specific artworks in their datasets without the artist’s consent. Fortunately, organizations like Stable Attribution are developing systems of accountability to work towards creating new datasets that artists contribute to willingly. It is critical for artists to lead the way in shaping laws and policies that affect AI-generated art in a manner that fosters creativity while still respecting the artistic labor and legacy of artists. If we don’t do this, someone else will—and if it’s the geriatrics who run the US government they will probably create an even bigger mess.

If you want to see the real dangers of developing AI technology, take a look at the latest GPT-4 Technical Report (https://cdn.openai.com/papers/gpt-4.pdf), which details the findings of the developers and testers behind OpenAI’s latest AI. In the document OpenAI admits that GPT-4 “is capable of generating discriminatory content favorable to autocratic governments across multiple languages.” Just as startling is the conclusion, GPT-4 exhibited, “the ability to create and act on longterm plans, to accrue power and resources (‘power-seeking’), and to exhibit behavior that is increasingly ‘agentic.’” Fundamentally its behavior is proving to be more and more autonomous. Now that is some scary shit.

-

SHOPTALK: LA Art News

Hammer, NY GalleriesHammering is Done

The Hammer Museum has been transformed, and it’s happened so gradually over the past two decades that we barely noticed it. Sometimes one section would be closed off, sometimes another, and every so often a new section would be unveiled. There’s the bridge that crosses the central courtyard, the revived restaurant, the spiffy gift shop and last year the dedicated space for works on paper, which is a jewel box of a gallery—literally, a box within a box to look at smaller works in an intimate space. Right now it’s featuring a wonderful retrospective of Bridget Riley’s drawings.

On March 26, the Hammer opened its completely renovated home, with several new exhibitions thrown in. “We altered every square inch of this museum,” says Director Ann Philbin. Kudos to Philbin, who had the vision to remake this building and this museum, bringing an obscure university museum into citywide and nationwide prominence. She’s also had the determination to raise the money—and to see it all through.

The building has never felt more of a whole, and the beautifully spun web of red twine that engulfs the entrance is a sweeping welcome which was made by Japanese artist Chiharu Shiota, with the help from UCLA students. Altogether, 40,000 square feet of new space has been added, and the museum now spans the entire block along Wilshire Boulevard, with Michael Maltzan acting as the lead architect throughout.

There’s so much to say, but let’s take a look at the two corners on Wilshire. They’ve moved their main entrance to the corner of Westwood and Wilshire, although you have to approach it from the side, up a ramp from Wilshire and towards the corner. Meanwhile that corner has now become a small, raised platform to wait for your friends or take a moment to pause. It’s a great way to transition into the museum, and in a chat with Maltzan, I learned that they had that move in mind.

The other corner now has a small outdoor patio, currently occupied by Sanford Biggers’ gigantic and rather mysterious bronze sculpture, Oracle, based on an ancient statue of Zeus, but this one with an African American head. Inside is a new media installation, Particulates, a spectacular laser-light work by Rita McBride.

Desert X 2023 installation view, Lauren Bon, The Smallest Sea with the Largest Heart, photo by Lance Gerber, courtesy of the artist and Desert X. Desert X

It’s been a particularly good year for Desert X in the Coachella Valley, with a new sensibility added by guest curator Diana Campbell. Campbell is the founding artistic director of the Samdani Art Foundation in Bangladesh and the chief curator of the Dhaka Art Summit. She grew up in Southern California and used to vacation with her family in the Coachella Valley, though now she is based in Bangladesh. While I don’t believe you have to be from the area to appreciate it, it’s no accident that two of my favorite installations this time around were also by artists who have spent time in the desert: Lauren Bon and Gerald Clarke, two of the 12 artists featured in this fourth edition of Desert X.

Bon’s piece, The Smallest Sea with the Largest Heart, takes place in an abandoned motel on the north end of Palm Springs, where it can only be seen in the evening when night falls. A steel-mesh sculpture modeled after the heart of the blue whale slowly rises out of the murky waters in a swimming pool lit by a single underwater light. The water has been trucked from the polluted Salton Sea—Bon suggests whales used to be in these parts. Someone is hand-cranking a pulley to lift the sculpture out, then they slowly let it drift downwards, as the crackling of static gets louder and louder.

Not far away, in a stretch of land by a community center,

Gerald Clarke has created a gameboard you can walk on, Immersion, with a maze pattern based on basketry of the Cahuilla community of Indians. In this one you advance by correctly answering questions about Native Americans. The goal, he says, is to get to the center of the maze-like layout. “I hired two scholars of Native American history and culture to create the questions,” he says, “and then I went over them.”

Gajin Fujita’s exhibition “True Colors” at L.A. Louver. Courtesy of L.A. Louver. Comings and Goings

They’re still coming! Yet more new galleries keep popping up. Only recently did I finally visit the three Nino Mier galleries on Santa Monica Boulevard—smallish spaces showing paintings and ceramics. It’s an interesting strategy, to grab small available storefronts and treat them as you would different spaces in a big gallery. They are very close together, so you can walk from one to another.

Earlier this year Sean Kelly Gallery opened up its first outside-of–New York branch on North Highland. It seems the trend to take old buildings and renovate, sometimes even add to them, making sure you have an outdoor space for parking and for receptions, as needed. Lisson, which just opened in mid-April, was able to celebrate with such a space—the parking lot was used for a very lively reception with bar and grill. Their show of Carmen Herrera is a standout—the longtime adherent to geometric abstraction died last year at 106.

Next up are openings of new spaces by James Fuentes, Marian Goodman and David Zwirner. The latter has put off their LA opening so many times, I’ve stopped trying to chase down that news—but they’re opening with a show by Njideka Akunyili

Crosby. Her painting at the Hammer’s current group show is one of the most memorable, and she has a mini show at the Huntington.Last but definitely not least, I have to add that one of the best solo shows up is at our own homegrown L.A. Louver—

Gajin Fujita’s “True Colors.” He’s a master of meticulously crafted and beautiful paintings which mash up Japanese woodblock and LA street-art aesthetics. There are samurais and geishas swimming amidst graffiti tagging, and also a very moving portrait of his sweetly smiling mother, with a small elephant in the background, as she slips into old age.

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,