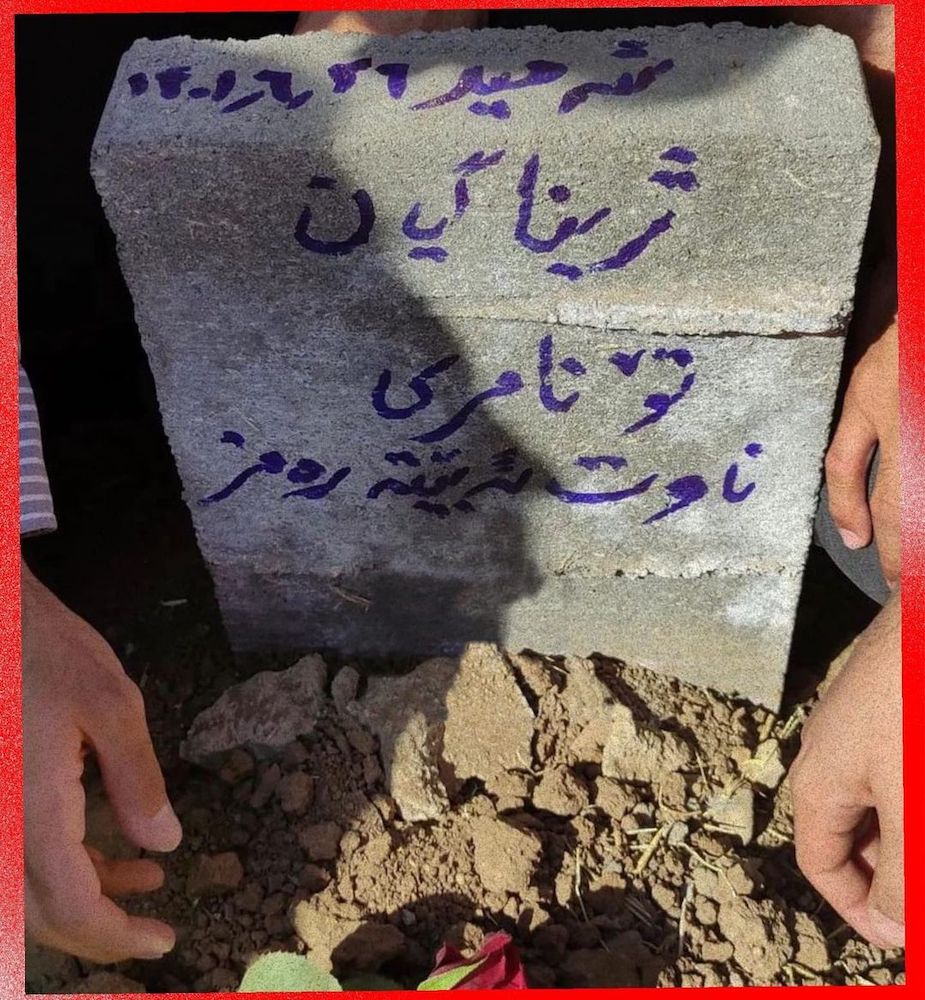

It began with marker on concrete: “Dear Zhina, you will not die. Your name will be a symbol.”

Zhina was the Kurdish name of Mahsa Amini. On September 13, 2022, the 22-year-old was arrested by Iran’s “morality police” for wearing her headscarf too loosely. While in custody, she was murdered. Mahsa’s grandfather wrote those words on her gravestone.

#MahsaAmini did become a rallying cry, igniting worldwide protests on behalf of “Woman. Life. Freedom”—“Zan. Zendegi. Azadi.” Protestors in Iran took to the streets—and continue to do so—despite lethal crackdowns, sexual assaults and poisonings. Women removed their hijabs and cut their hair. At the same time word of #MahsaAmini and #IranRevolution spread on social media and the protests expanded. Iranians expressed their exasperation over the repressive regime of President Ebrahim Raisi and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei with its economic woes, corruption, floods, droughts and ban on dogs. The litany of woes was captured in Shervin Hajipour’s Grammy Award-winning protest anthem “Baraye” (For The Sake Of).

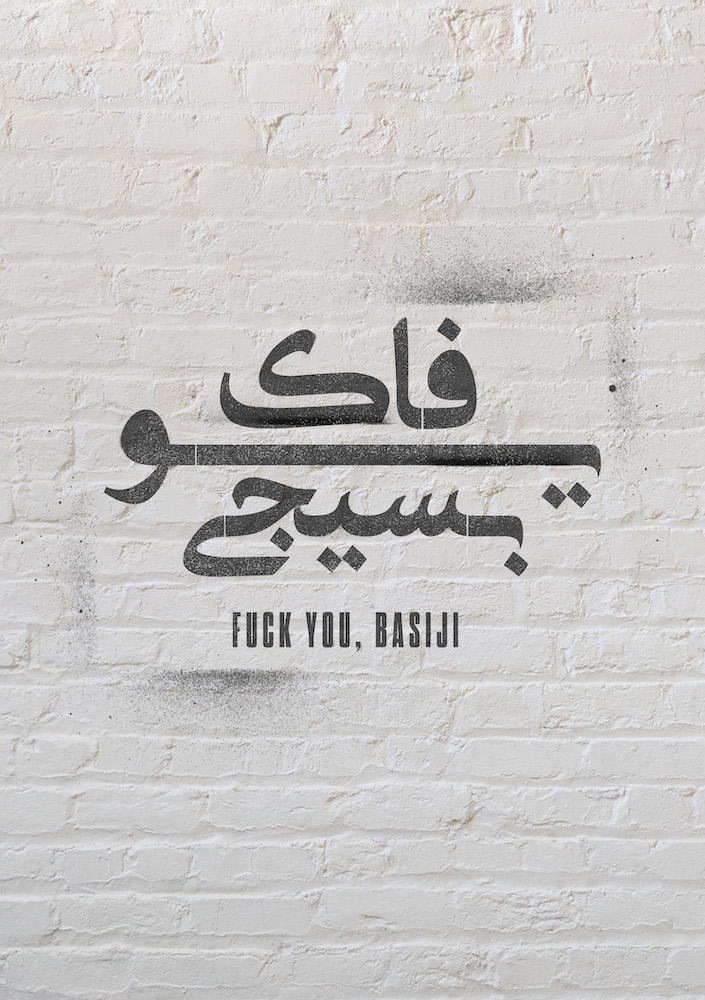

In the early days of the revolution—just as they had with previous uprisings—the Islamic Republic shut off the country’s internet, and the protests continued with spray-paint on bricks: “Resistance is life.” But the Islamic Republic was ready with buffers and white paint, because this is a regime that understands the power of words and images on a wall.

Public mural in Tehran defaced with paint. Photographer’s name withheld for their protection.

Following Iran’s 1979 revolution, the Islamic Republic embarked on a propaganda campaign of polluting Tehran’s visual space with large-scale murals on public and private buildings. In the early 1980s, murals featured the supreme leader of the revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. During the Iran–Iraq War, depictions of “martyrs” killed in the “Imposed War” headlined Tehran’s multi-story buildings, rendered in bright primary colors and Islamic green. Iranian-American anthropologist Roxanne Varzi said, “It was the war that ultimately defined the Islamic republic as an image machine.”

Regime-sanctioned muralists have kept the machine running. In 2020, a US drone assassinated Iranian General Qasem Soleimani for his key role in coordinating bombings and other hostile actions. On January 2, 2023—the third anniversary of his death—the country’s largest mural was raised above Enqelab Square in central Tehran: a 15,000-square-foot billboard of Soleimani flanked by other “martyrs of the devotees of the nation.”

Hijabs and walls are synecdoches for the regime. The Islamic Republic controls what is seen and covered; they regulate the heads of Iranian bodies and buildings. No wonder, then, that some of the first acts of revolution were Iranian citizens removing hijabs and knocking the turbans off of mullahs. And perhaps it’s not surprising that numerous Instagram photos of graffitied walls are accompanied by women posing without hijabs and, sometimes, with lifted shirts.

Mahsa Amini’s grave. Photographer’s name withheld for their protection.

The regime had failed to recognize the tacit refinement of another image machine. These revolutionaries had grown up beneath a sky overcast with propaganda murals; and on phones and computers inside these decorated buildings, they, too, had mastered the power of words and images.

In response to the regime’s rapid erasure of graffiti, protesters began dating their messages: “Death to Khameni – October 16th.” When Iranian authorities whited out “Woman. Life. Freedom.” on a bank’s door, Iranian citizens painted over that with: “Blood cannot be cleaned with anything.” In honor of Mahsa Amini, and all she symbolized, Iranians invaded roofs and poured paint on those state-sanctioned murals, smearing Khameni with dripping blood-red color.

Mahsa and her generation grew up in the literal shadow of violent and repressive men. They are now coming into the light, removing their hijabs, hanging them from Tehran billboards, and reclaiming the country—and walls—for themselves.