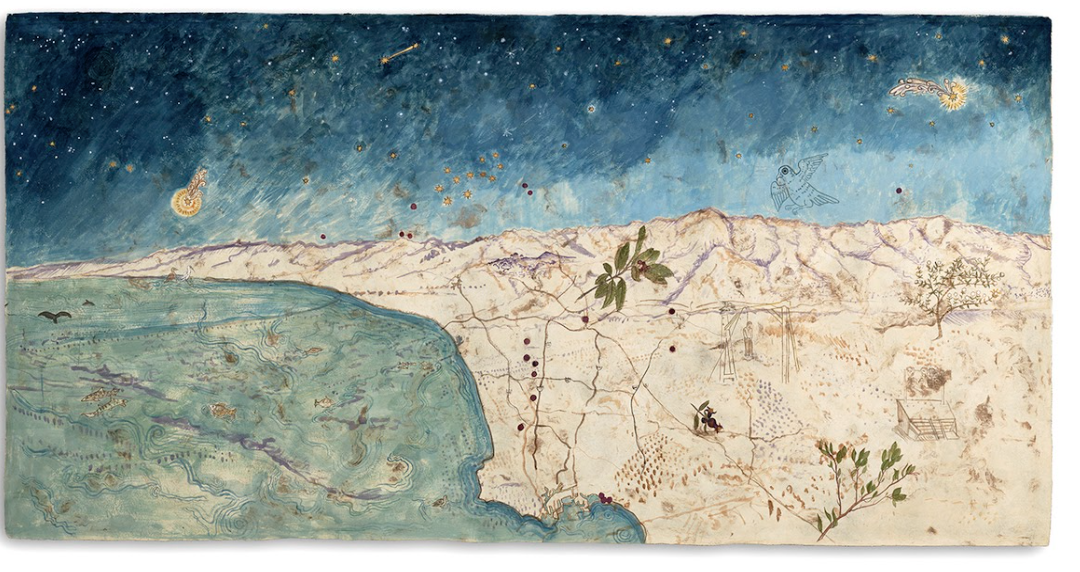

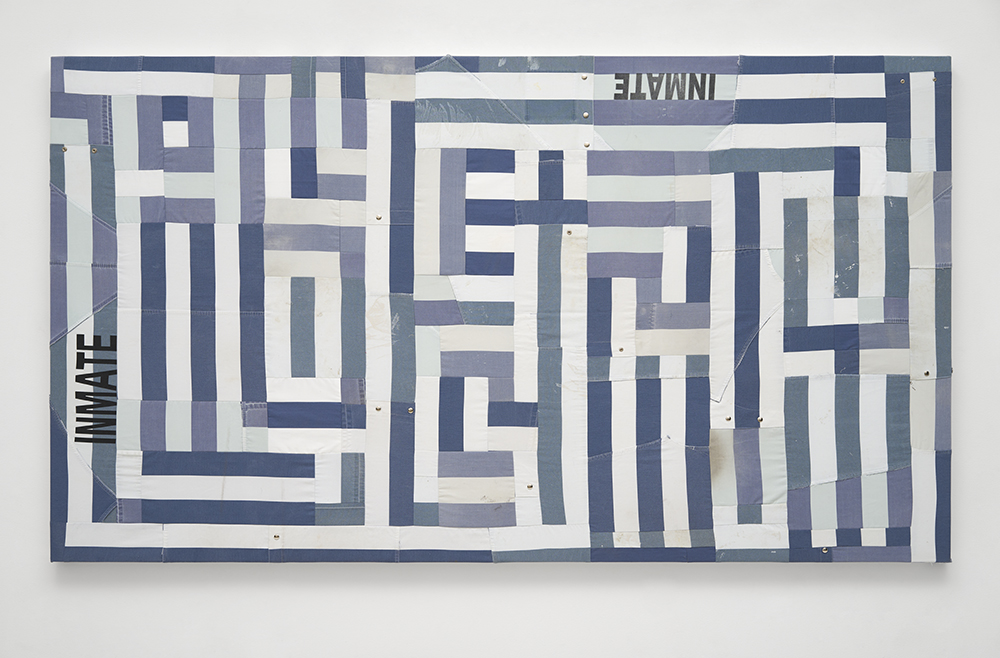

Congratulations to our winner Lisa Joy Walton and our finalists. Lisa's photo is seen above and first in our photo gallery in the January/February 2022 online edition of Artillery. The following photographs are the finalists. Please see the info below on how...