Your cart is currently empty!

ABSTRACTION STUDIES George Legrady’s Collaborations and Mythic Narratives

Generative AI image synthesis, exemplified by software like Midjourney, DALL-E, Stable Diffusion and similar tools, has captivated widespread attention enabling on-the-fly image creation through text prompts and image prompts. While either text or image quickly produces an image, the challenge lies in the extent to which the input aligns with the image maker’s intentions, as the prompt is interpreted and reconfigured through a series of autonomous processes inaccessible to the user as the results are generated based on a model trained on billions of tagged images. The algorithmically determined selection of which image segments are chosen from the repository, their relative weight in relation to each other, the visual syntactic dissections and the composition within the new image space of the synthesized image, remain at this point beyond the image maker’s aesthetic influence resulting in a situation where content representation, aesthetics, stylistic renditions and visual element configurations are constrained by the data on which the model is trained. Given that the goal of AI image generation is to produce images that corresponds to the input data that the software has been trained on, there is a concern that much generative image art is devoid of new meaning because it recycles the conventional clichés embedded in the training set. However, my perspective on how AI can be a significant artistic medium in itself, is based on a longstanding ongoing engagement with imaging technologies to result in visual and cultural representations.

I began my artistic practice in documentary photography transitioning to street photography, and then to pictorialism, and eventually to staged photography and conceptual photography where, in my case, the primary goal was to articulate the ways in which photographic technologies imposed a meaning onto the images they produced. A brief fortuitous meeting in the summer of 1981 with the pioneer AI artist Harold Cohen prior to laptop computers, resulted in Cohen generously giving me access to his mainframe computer for a number of years, an invaluable opportunity to acquire computing coding skills with the perspectives of how coding could be a form of artistic expression. Cohen’s posthumous retrospective at the Whitney Museum this winter (2024) curated by Christiane Paul, addresses his historical contributions to computational aesthetics by reconsidering digital technologies as an area for intellectual investigations to address the question to what degree can an image made by a machine be differentiated from one made by a human. Inspired by his investigations to translate his own painting process into computer code so that the computer would autonomously produce Harold Cohen artworks, I had to wait till the mid-1980s for the first digital photographic imaging system to be introduced, so that I could then creatively explore the potential of computer code as an artistic medium in itself by which to transform and create images within the digital photographic format.

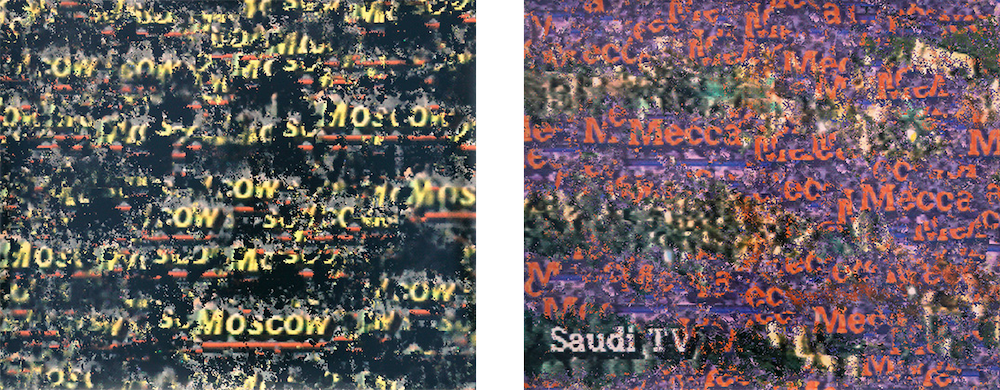

In the 1990s, data integration into mainstream culture gained prominence, also including the art world, possibly influenced by conceptual art practices. In 1998, I presented Tracing, a digital data installation at LA MOCA curated by Julie Lazar. Initially commissioned by a German museum, the artwork aimed to juxtapose cultural perspectives from two distinct sets of data. One set, collected in San Francisco during its tech boom, and the other gathered in post-Soviet Communist countries. The data, comprising texts and videos, was projected on large screens on opposite sides of the exhibition space. Viewers on one side interacted with a computer mouse to select data, while sensors on the other side recorded audience positions and movements in the gallery space to determine the projected content. The installation sought to compare the socio-political landscapes of the technological rise in one world against the collapse of socialist states in another. The exploration extended to human-technological interaction, contrasting active human agency in data selection with autonomous selections based on audience positioning recorded by sensors. Another notable project exploring the interplay of visual data, language labeling and technological processing akin to contemporary generative AI is “Pockets Full of Memories” which premiered at the Centre Pompidou Museum in 2001 and exhibited internationally until 2007. The installation invited the public to scan objects in their possession and describe them through a questionnaire. Using an early AI neural-network algorithm, the objects were visually classified and clustered on a large screen based on the descriptions rather than their visual similarities. The installation aimed to investigate the impact of linguistic description in comparison to visual recognition, to highlight variations in how we perceive and describe things.

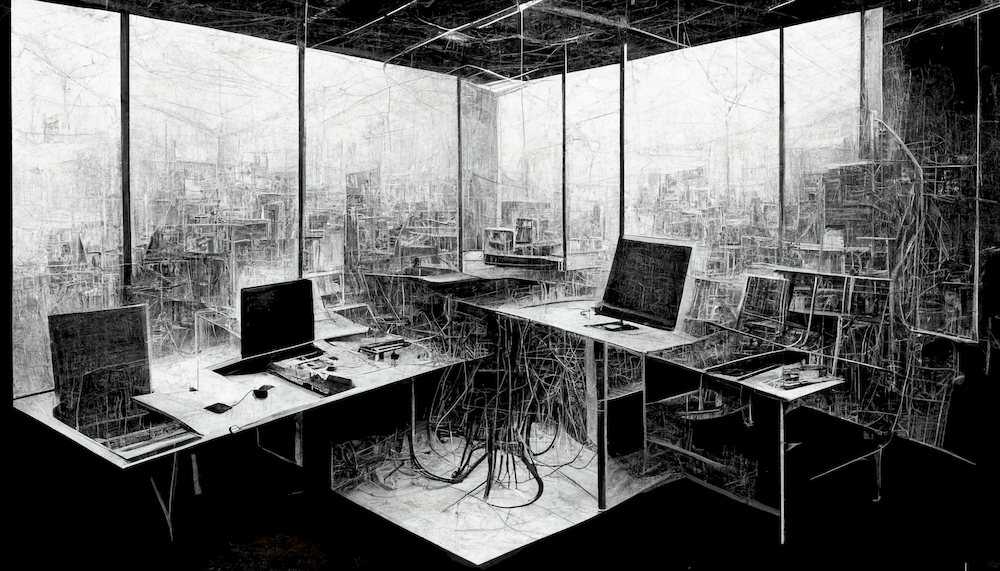

As images generated by Artificial Intelligence software are synthesized from pre-existing images and therefore predominantly reiterate styles, social values and cultural narratives encoded in the repository, image practitioners seeking to innovate with AI software face the challenge of how to go beyond the constraints to arrive at results that can be considered as distinctive. In my studio’s explorations with Midjourney, versions 3 and 5, and Stable Diffusion, once an image is obtained that meets the desired intent, our primary approach has been to recirculate the resulting image as an input prompt to propagate variations. This iterative operation, referred to as img2img (image-to-image), generates modified versions because each time an image is reused, it introduces variances that can be minute or large, and like evolutionary change, content and aesthetic enhancements are introduced resulting in differences that can be selected as needed.

Artistic expression may be characterized as emerging from the interplay of intention and experimentation that guides exploration. The artist’s control over generative image synthesis is limited to two key factors, first the choice of text or image input, and second, the curation or selection from the set of generated images. The overarching question is to what extent can a machine-generated output, initiated by a human textual input, be regarded as one’s own creative expression? Commenting on the process, artist Philip Pocock emphasizes that “the choice of image nowadays is a new form of framing the image.” The process of selecting generated images as opposed to creating them, is nonetheless shaped by informed sensibilities. These choices are intertwined with various impulses, imaginings and memories, and ultimately fall within the realm of one’s own expectations.

AI image creation can best be understood as an outgrowth of a long historical tradition of inventing technologies that serve the image-making process. For example, historical arguments have been proposed that define the invention of the photographic camera as an instrument that embodied the technical elements and instrument design dictated by the conditions to produce pictures. Photographic activity can then be considered as not so much as an instrument for documenting events in the world, but rather as a practice that investigates how scenes captured in the world look like once translated into an image.

Early 20th-century industrial production introduced the possibility of using language to describe the creation of an image as when the Bauhaus artist László Moholy-Nagy telephoned a set of instructions to a factory in the 1920s to produce images without the need to be on site to direct production or make the work himself. In this example, the rudimentary visual design made it possible to be communicated telematically as the describable forms organized within the rectangular pictorial space could be accurately described according to their geometric shapes and positioning.

With AI image synthesis, the paradigm shift in writing a descriptive text prompt resulting in a realistic-looking image is a consequence of the increased complexity of both how language is parsed by today’s advanced language analysis software, and how an image can now be numerically construed from data, given that digital images are essentially a stream of numbers organized into what we describe as a two-dimensional organized set of discrete pixels, each pixel having precise numerical values for its location, color and brightness values. The process of diffusion in AI image synthesis where legible images emerge through the removal of noise occurs at the pixel level where the relationship of adjacent pixels is altered to arrive at visual details that simulate our expectations of a realistic image. Prior to AI, artists with programming skills, who wrote software to create images with computers had to first imagine and then articulate it precisely in programming language to result in a desired outcome. In this approach, artists encode their aesthetic intentions into language (computer code) to arrive at the intended results, much like calling in a set of details, colors and positions by phone as exemplified by Moholy-Nagy’s telephone pictures.

Many commentators have raised critical concerns about the unintended transmission of cultural values and ideologies embedded in the training sets used to create AI images. Users of AI software may be unwitting disseminators of belief systems and embodied values by which the software have been designed to advance so-called “realistic” representations. As an exercise in critically analyzing how culture and society encode and shape societal values, the French semiotician Roland Barthes in his book Mythologies published some 70 years ago, proceeded to select articles published in the daily news to dissect and comment on the underlying encoding of value systems with the intention of explicitly revealing the biases but also to refine the operational semiotic structures by which to analyze how the encoding of values was probable. As a creative user of AI generative imaging technologies, I look forward to a similarly functioning “Myth Filter” through which AI-generated text and images can be filtered to reveal and critically articulate the encoded ideological value systems expressed through the generated result

Comments

One response to “ABSTRACTION STUDIESGeorge Legrady’s Collaborations and Mythic Narratives ”

Thank you for a fascinating, articulate account of the inner workings of AI imaging. I will try your system of choosing and more detailed prompts to see if it yields anything I can work with but I have doubts. My experience with Midjouney has been disappointing because the results are predetermined by an archive of imagery that is essentially banal and conventional.

I’m puzzled by your acknowledgment of Barthes’ demythologizing the codes embedded in the photograph, while simultaneously calling for an AI filter to accomplish essentially the same thing. Thanks to Barthes, Sontag, Baudrillard, and a host of other seasoned critics, with the aid of the rise of MFA programs prior to the new AI, we are now all versed in the finer skills of decoding. The sheer amount of writing done on this is a testament to the astonishing attraction of the photograph as an object of intellectual and critical inquiry. Critical thinking we will have, with or without AI.

At the current rate of AI learning, it would seem that a myth filter is about as far off as cross-referencing AI imaging with Barthes and Sontag texts – presuming the AI overlords want such a filter, or does AI itself make that decision? Is AI capable of the kind of critical thinking that seeks independence from the status quo that is about to burn us all alive or will that require the development of an anti-AI AI? If AI becomes capable of removing codes do I want it to do my decoding? (I might begin to trust it.)

The problem with Midjouney is exactly what you have pointed out in such fine detail, that it is one-dimensional – a hall of mirrors built on billions of known, coded, already-seen imagery.

In the early eighties I was doing darkroom work for Woody and Steina Vasulka in Santa Fe, who generously gave me a key to their studio while they were traveling Europe and the U.S. so I could manipulate photographs on their waveform generator. In the spirit of Woody and Steina, provocateurs and mad scientists of the highest order, I sense that it’s not an AI with a decoding filter we already have on our own that we need, but a way into AI so that it will unwillingly turn the myth on its head – a waveform generator to the 100th power. What I hope for is a way to fuck with it, and I just don’t see one yet.