Memory is a funny thing. Do you remember skinning your knee when you were a kid, or do you just look down at the scar and think of the stories you’ve heard? As you drive down the first street you lived on, do you remember the market on the corner where you would get ice cream on hot summer days? What is the difference between a memory and a story? Does one have more value than the other? Are either based in reality or does that even matter?

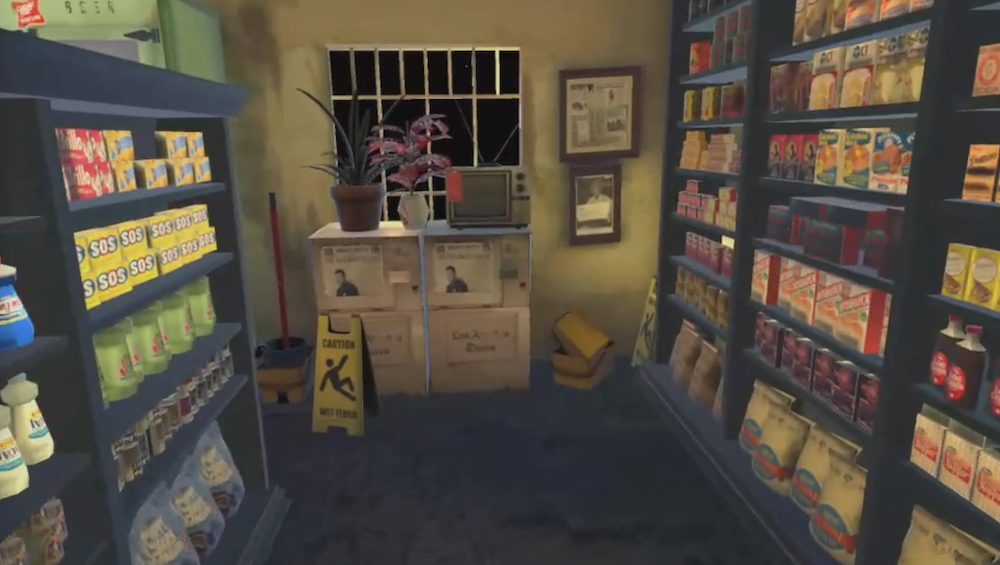

As I stood in a nearly empty room at the Japanese American National Museum and interacted with Aki’s Market (through oculus googles), I didn’t see someone’s quickly assembled CliffsNotes. I saw a rediscovered defining chapter in a family’s/nation’s history. It was a place torn somewhere between a dream and a memory, a place of value to Japanese- American history, to Southern California history, to East LA history. A once-forgotten corner store that now exists digitally again—thanks to its re-creator Glenn Akira Kaino.

The original Aki’s Market existed in both a time and locale within American history that some may wish to forget. Shaped by the experience and memories of an entire ethnic population imprisoned by the US government (including the future owners of Aki’s Market) and set in an East Los Angeles area better known at that time for homicidal gang activity rather than for members giving, building and uplifting the community, there existed Akira Shiraishi, “Aki.” By all accounts Aki (Kaino’s namesake—whom he never met) was a formidable man both in stature and heart, yet the stories were few and far between as Kaino grew up.

Glenn Kaino, stills from The Store, 2023, VR equipment, mixed-media installation, courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

In conversation with Kaino after viewing the exhibition, I began to understand that the show was not at all about the objects (whether physical or digital) but more about the conceptual nature of memories, both personal and communal. It was an exploration of family, community and the unknown stories you have been told. We often share the least with those the closest. We hold our fears, our mistakes and many of our triumphs from those we claim to love the most. What does it mean when we look deeper into what we are told? What trauma is found, what perseverance is exposed? If you look closely, if you ask the right people, if you search for the spirit that you’ve heard of—sometimes the facts are so much more inspiring than you could have dreamed.

What was manifested for the exhibition was simply an extension of the exploration of Kaino diving deeper into relationships with family, community members and historical documentation to learn more about Aki. To be clear—the art was great. It does exactly what it should. It takes you to that intrinsically special place only profound art can do. It doesn’t try to be more than it should. It doesn’t try to put you in a place of true VR, of interacting like some first-person video game. That’s not what Aki’s Market does. Rather, it puts you in the confusingly beautiful moment where you wake up from a dream and struggle with whether it was a memory or a dream.

With assembling communal memory, we think about what we have been told, by our moms, by our uncles. By someone that just passed through 25 years ago and had an opinion because everyone has an opinion: “That’s not how it was. I was there, It was like this. “The Donuts were over there. The Levis were here. The Coca-Cola display was there.”

In reality, there wasn’t any Coca-Cola. The store sold Pepsi. So, who remembered it correctly? More so, does it matter? It may matter to some—to me, it matters less and less. I am a writer; I love a well-told story. I remember bringing my daughter home for the first time. I remember skin-to-skin before leaving the hospital. I looked at that picture today. Do I remember bringing her home? No, I don’t. What I do remember is taking her out of the hospital and not knowing how to put the car seat in. Do I remember turning onto our old street in East LA and passing by Aki’s Market less than two minutes from unloading my precious cargo? I do not remember it, but now it is a part of the story I will tell moving forward