The guise of the paint-slinging hero never quite fit William T. Wiley, whose early folksy, Western-styled brand of funk art, fueled by Abstract Expressionist and conceptual underpinnings, atrocious puns and general anarchy, was christened “Dude Ranch Dada” by Hilton Kramer in 1971. Wiley’s body of work, stretching over five decades, has included diverse works in media ranging from watercolor to performance art. His “Newslate” at Hosfelt Gallery surprisingly includes a striking body of large, predominantly expressionistic canvases that suggest, at times, landscapes of Turner and El Greco or the art of some primitive culture. Throughout, Wiley’s poetic feel for language and wordplay brings his voice into the conversation a viewer has with the paintings.

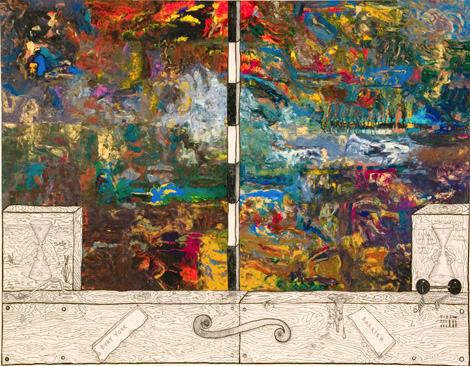

Facing the entryway, Bury Your Barrier (2006) is a large canvas bisected vertically by a thin strip of narrow rectangular segments in tan and gray, divided horizontally by a thick band of raw canvas housing charcoal drawings at the bottom. Dense, richly-hued markings fill the upper areas with swirls of violet, ocher, cadmium reds and alizarin in a loosely-defined sky/landscape suggesting a conflation of paradise and the apocalypse. Wiley’s hourglass character “Buster Time” stands below with arms akimbo, a dumbbell at his side: “Yo Time, Lookin GOOD, Buff DouBT, EVEN, BE HERE WHENEVER.”

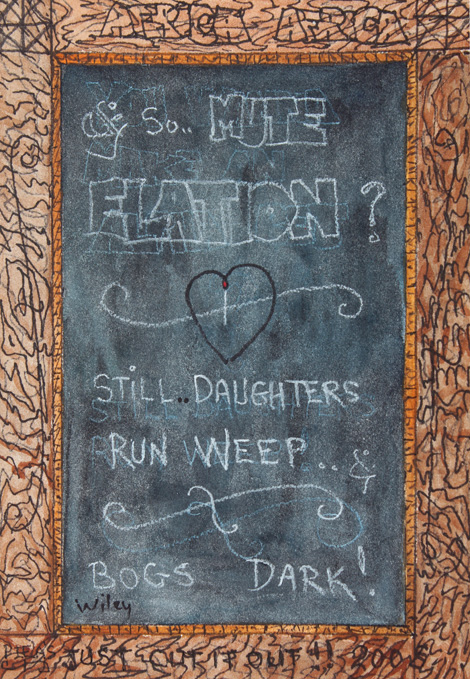

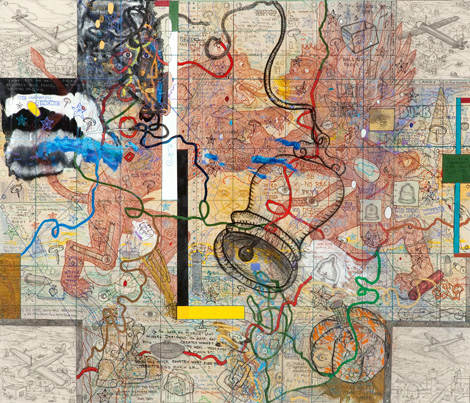

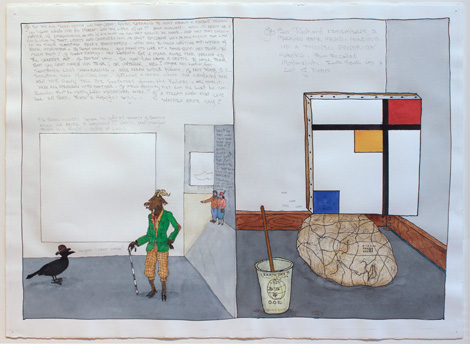

No Bell Prys for Peace with Predator Drone (2010) features battling alchemical lions with wings and crowns, elegantly sketched in a rust color. “WHY ITS AN UN-FINISHED MASS TOUR PEACE…HE SAID DRONING ON & ON…” This work obliquely chastens laureate Obama for his continuing use of robotic hit men. Across the room, a collection of small watercolors depict a child’s chalkboard slate, another trademark image, scrawled with text, addressing issues ranging from mortality to female circumcision. In & So Mute Elation (2008) Wiley twists language to express rage “STiLL DAUGHTERS RUN WEEP.” A number of lively, lyrical watercolors rounds out the show, including Goat and Raven at the Museum (2010), where a beautifully-drawn goat with knickers, a cane and green waistcoat meets a dapper raven—“oh yeah cream astor!” a jab at “Matthew Bar Knee.”

Aside from the verbal and visual pyrotechnics at play here, there is something else afoot, something dark and brooding. Wiley’s work has always had a certain dark side, a humor that is both self-deprecating and sarcastic, an unflinching willingness to grapple with chaos and ugliness, an obsession with stirring up trouble in the form of political content and idiosyncratic allusions. In the raw space of Pre-Tsunami Abstraction with Migraines (2011) we find “So the MISSIN CORNER, THE hissing MOURNER.” Largely monochromatic swirls of black, white and gray eddy around, as though water avoiding rocks; what looks like a sheep’s head emerges from the marks in this writhing work, as ghostly heads stream upward. Recent NPR stories have revealed an epidemic of survivors of the Japanese tsunami who believe they are haunted by the spirits of those who were lost. Clearly likewise bedeviled by the sorry state of humankind, “Newslate” reveals a resolute Wiley—haunted yet undaunted.