As I rush to post this, I’m already thinking the title is either an overstatement or understatement and outrageously disingenuous either way.

Let me step back for a second (I’m going to be stepping back all the way through this, so just get used to it). This is about the way we live today. (Yesterday, too.) More specifically, it’s about the way I live and where I live, and the problem I have with that. I live in Los Angeles and have lived here for something like a quarter-century now. A lot of people think I live downtown, but actually I don’t. I live—in classic L.A. fashion—in one of those neighborhoods carved out of bits of Hollywood (which, in L.A.’s industrial ecology, is a ‘factory/showroom’ section of town) and (suppressing a gag reflex here) suburbia.

You read that right. My quasi-ideal urban village is only a couple blocks from suburbia. Okay, it’s also cheek-to-jowl with Hollywood and proximate to a Metro station that beelines downtown; and that suburban greenbelt includes a number of house-and-garden-tour-worthy houses encircling Griffith Park. But there’s no escaping what it is.

And this is where loathing gives way to self-loathing. Although I walk or bike in the neighborhood, for all the convenience of the Metro, I can count the number of times I’ve taken it downtown on one hand. I rarely use buses in Hollywood and Wilshire District neighborhoods—even when it might be more convenient (especially when you factor parking into the equation). No—instead….

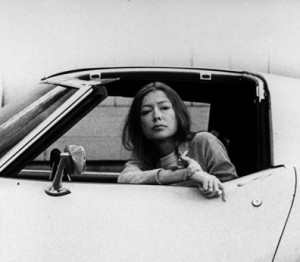

I drive a car. This, too, is classic L.A.; also mortifyingly common. Since the mid-20th century, the automobile has gone from L.A.’s dominant mode of transport to the status of a cultural icon. (This has always been profoundly depressing to me.) L.A.’s metastatic suburban development would not have been possible without it. (And its continuously expanding development has ensured that it will remain a necessity for years to come.) Long before iPhones and iPods (and for that matter the Walkman before them) locked us into our own mobile cocoons, the automobie came to define a quintessentially Angeleno alienation—reinforced by the eddying concrete canals that detached us from our crazyquilt of industrial, commercial and residential suburban neighborhoods. Our sense of destination is always slightly vague here, warped by the outsize distances we traverse, the imposed discontinuities of hopscotching neighborhoods freeway exit after exit; distorted by the scale of streets and boulevards enlarged to accommodate our cars, which in recent years have also exploded to cancerous—or at least militarized—proportions, taking an ever heavier toll on street surfaces. Public places and commercial venues still identify their locations by proximity to freeway exits and interchanges as much as by street address. Until relatively recently, neighborhood was treated as secondary to freeway accessibility.

I drive a car. This, too, is classic L.A.; also mortifyingly common. Since the mid-20th century, the automobile has gone from L.A.’s dominant mode of transport to the status of a cultural icon. (This has always been profoundly depressing to me.) L.A.’s metastatic suburban development would not have been possible without it. (And its continuously expanding development has ensured that it will remain a necessity for years to come.) Long before iPhones and iPods (and for that matter the Walkman before them) locked us into our own mobile cocoons, the automobie came to define a quintessentially Angeleno alienation—reinforced by the eddying concrete canals that detached us from our crazyquilt of industrial, commercial and residential suburban neighborhoods. Our sense of destination is always slightly vague here, warped by the outsize distances we traverse, the imposed discontinuities of hopscotching neighborhoods freeway exit after exit; distorted by the scale of streets and boulevards enlarged to accommodate our cars, which in recent years have also exploded to cancerous—or at least militarized—proportions, taking an ever heavier toll on street surfaces. Public places and commercial venues still identify their locations by proximity to freeway exits and interchanges as much as by street address. Until relatively recently, neighborhood was treated as secondary to freeway accessibility.

Which is so wrong. Which also brings us back to that business of cultural icons and civic symbols. Lacking any readily identifiable skyline, with its landmarks scattered about the L.A. basin, for any number of years until not so very long ago, L.A. would be identified simply by a stack of freeway interchange cloverleafs—an apt, albeit dubious, civic emblem. L.A. was above all a city in constant motion, always rushing to the next place that dissolved mirage-like as the next exit came into view; as if running away from what it had been, in a rush to get to what it was going to be; not only living in denial of its roots, but seeming to deny it ever had any. This was not entirely without success. Somewhere between the post-World War II era and the 21st century, facilitated to some extent by international migrations, Los Angeles went from factory town to international city.

Given that my psychological state is a more or less constant state of denial, it could be that I’m living in the perfect place. But I’m not happy about it. L.A. may be an international city, but it’s still a factory town. (Off the red carpet, it even dresses like a factory town.)

Which leads me to my trepidations about recent developments in and around the arts community (both physical and virtual) here in Los Angeles. Speaking of the ways we get around (or just think we’re getting around) here, I should be excited about the next Industry project looming on the horizon, titled (at least for now), Hopscotch. I cast a virtual vote for its production (for LA2050 challenge grant funding). Who wouldn’t? The Industry is one of the most exciting companies of its kind in the country, maybe the world. (I’d call it an opera company—they might, too; but it’s really more than that: opera/theatre/music/performance—and every kind of hybrid of these arts.) If you saw their production of the Christopher Cerrone opera of Calvino’s Invisible Cities—a transcendent, transformative experience by any definition—you would be one of those insisting that means be found to keep the funds flowing.

Which leads me to my trepidations about recent developments in and around the arts community (both physical and virtual) here in Los Angeles. Speaking of the ways we get around (or just think we’re getting around) here, I should be excited about the next Industry project looming on the horizon, titled (at least for now), Hopscotch. I cast a virtual vote for its production (for LA2050 challenge grant funding). Who wouldn’t? The Industry is one of the most exciting companies of its kind in the country, maybe the world. (I’d call it an opera company—they might, too; but it’s really more than that: opera/theatre/music/performance—and every kind of hybrid of these arts.) If you saw their production of the Christopher Cerrone opera of Calvino’s Invisible Cities—a transcendent, transformative experience by any definition—you would be one of those insisting that means be found to keep the funds flowing.

On a certain level, even the title makes me a little nervous—not only in the way it very precisely describes an aspect of the Los Angeles automobile experience, but also a certain mode of experience, an outflow and description of what we might call the pathology of Los Angeles. I think it‘s no small coincidence that the working title cannot fail to remind some of us of the mid-20th century novel by Argentine writer, Julio Cortázar, Hopscotch (Rayuela) (There’s almost a poetry of coincidence here: one of the main characters is called ‘(Manolo) Traveler’—an apt follow-up to Calvino’s saga of that echt Traveler, Marco Polo.)

Thinking back to that book, I wonder—are we (the audience) meant to be the ‘Morelli’s’ here? (I’m not going to try to re-hash the book here, but the device implicates the reader as a kind of co-conspirator and co-author.) It’s not as if we haven’t read stories or seen movies that ‘hopscotch’ over Los Angeles by way of characters and subplots moving around in cars. The plot of The Big Sleep (Hawks/Chandler/Warner Bros., 1946) could almost be described in this fashion. (And there are many others.) Nor for that matter are films noirs and similar novels or stories alone in drawing us into an implication of guilt, co-conspiracy or shared indictment.

But that’s just it: we are guilty. It goes back to the core pathology: an ecosystem all but destroyed by the internal combustion engine; a community and urban fabric disfigured and dismembered by the dominance of the single-passenger automobile.

I realize there are certain controls on the physical project, in terms of routes through traffic, scheduling, culmination at a ‘central hub’ (apparently at SCI-Arc), etc. In some ways, the planned peregrinations remind me a bit of some of the first performance art I ever saw in Berkeley and Oakland in the 1970s, which were revelatory and exhilarating. But Hopscotch seems to carry a certain dread. I keep coming back to the ‘18 cars.’ I can already hear the honking of car horns; they’re honking at me.