Maybe every gesture that you make can birth a fresh way of living. Perhaps by merely looking over your shoulder, or touching the ground, you can create a brand new philosophy or a radical break with reality.

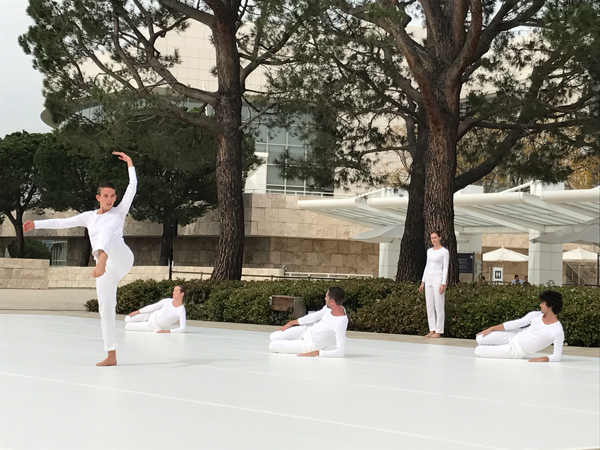

So argued the dancers in the Trisha Brown Dance Company at the Getty Museum last Friday, on March 10. The nine performers assembled in the Getty’s Tram Arrival Plaza at 2 pm, all dressed in white, and wearing sunglasses to guard against the glare reflecting from the white pad covering the museum’s travertine plain. A small clan of spectators gathered on the court’s ascending stone steps, awkward and blinking beneath the sudden sun.

The dancers milled about on the periphery. At an invisible sign, a man walked out onto the stage, unaccompanied by music. No one introduced him; no throat-clearing speech announced the break between expecting and making art. The trees framed the dancer’s sleepy arm stretches and head-rolls, which gradually escalated into leaps and lunges. He did not look at us, the audience; he did the thousand-yard stare of the star concentrating on his form. Then he slowed down and stopped; his face took on a placid, welcoming expression. We clapped.

A group of five quickly followed. One woman, with her head half-shaved, dominated. The dancers swarmed the area, curving beneath her stamping geometry. They formed into pairs and collapsed on the ground. They propped each other up as if at an impromptu picnic, trying to get comfortable as they leaned and tugged on each other’s limbs. For brief moments, luminous abstracts appeared – a triangle formed of crooked legs, a circle made of entwining torsos. Or were the dancers making shapes less cubist than neoclassical – like the disarmed magnificence of the Getty’s own Air by Aristide Maillol? The dominant woman with the shaved hair faded away without an argument. The dance unraveled spontaneously, as do the compositions made by people waiting in lines and sitting at bus terminals.

Trisha Brown, a MacArthur and Guggenheim fellow, formed her company in 1970, retiring as head of in 2013. She became famous for her astonishing site-specific performances, such as 1971’s Roof Piece, where dancers improvised and transmitted movements from the tops of twelve buildings in New York’s SoHo district. 1994’s If You Couldn’t See Me, which had Brown dancing all the time with her back to the audience, also figures in her pantheon. Brown additionally collaborated with a numinous collection of visual artists and musicians, such as Donald Judd, Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, and Laurie Anderson. Artistic directors Diane Madden and Carolyn Lucas now lead the group. They bear the mission of preserving Brown’s archives through re-enactments, such as in their massive Proscenium Works, 1979-2011 tour, which brought Brown’s dances to five different continents. The TBDC also initiated a review of Brown’s oeuvre in its Trisha Brown: In Plain Site series, of which the Getty performance formed a part last weekend, along with LACMA, the Broad, and Hauser, Wirth & Schimmel.

This august history of prior performance, however, did not strike the observer as much as the dancers’ immediate message that all human movement creates unscripted possibility. After the dancers lolling about in picnic-mode dispersed, two women took the floor. At first, they did yoga poses, specializing in one-legged downward dogs, as if at a sweaty Santa Monica studio. All at once, they then started heaving each other up aggressively like Hercules and Antaeus. A mixed-sex couple next gently stepped all over each other, transforming a matched battle into a domestic curio of passive-aggressiveness. Skreaky music began playing out of hidden speakers; a sound like a clock or a robot heartbeat tocked through the air. The audience sweated silently on the travertine, clapping lightly and tottering cheek-a-cheek on their similarly off-key sit-bones.

The best moment passed when the bellicose woman with the shaved hair appeared alone with a light aluminum ladder. As she played the contraption upon her body, she neatly shaped it into a prison, a toilet, a vagina dentata, an albatross, and—my favorite—a phallus of which all of us could be very proud. These metamorphoses blended together in swift, elegant progress, indicating that all matter could be thusly transformed with just an inkling of will. The dancers filled empty space with substantial tree-green shapes; they made a shrug or a hand-fillip into Renaissance sculpture just by making you notice it.

In the 1980s, the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari wrote: “You are longitude and latitude, a set of speeds and slownesses between unformed particles, a set of non-subjectified affects. You have the individuality of a day, a season, a year, a life (regardless of its duration)—a climate, a wind, a fog, a swarm, a pack (regardless of its regularity). Or at least you can have it, you can reach it. A cloud of locusts carried in by the wind at five in the evening; a vampire who goes out at night, a werewolf at full moon.”

What did they mean? I have no idea. But I grew closer to understanding when I watched the TBDC make the simplest signal pregnant with art. As I sat, bent and creaky, on the stone steps, I had the momentary hallucination that my every move, too, could be a moonshot. If I stood up from my seat just the right way, maybe I could also be a wind of locusts or a moody werewolf. And as I departed from the performance and caught a glimmer of my own reflection in one of the Getty’s manifold shiny surfaces, I couldn’t tell: Was that me, irradiated with potential? Or just the same old Yxta, shuffling along?

Photos by Yxta Maya Murray