Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Yxta Maya Murray

-

Anne Austin Pearce: Her Blue Period

River Deep–Mountain High at Founders Gallery at Soka University, Aliso ViejoWhat is a colorist painter? In the 19th century, the painter and critic Eugène Fromentin assessed that the work of colorist artists engage hues that are “rare, tender, or powerful, but resolutely [achieved by] a man skillful in feeling distinctions, or in rendering them.” Today, colorists might be defined as artists who use striking pigments to ask new questions about art and society: practitioners include Barbara Friedman, whose stunning, funny and risk-taking paintings talk back to the Color Field pioneers, Stanley Whitney, who challenges the canon with his stoplight-yellow and candy-pink grids that quote Agnes Martin, and Jeffrey Gibson, who currently represents the US in Venice with prismatic, multidisciplinary work that comments on Indigeneity, conquest and queerness.

In Southern California, Anne Austin Pearce offers a rousing contribution to this genre of art with “River Deep–Mountain High,” her new exhibition at Soka University’s 8,900 square-foot Founders Gallery in Aliso Viejo. Pearce, who was born in Kansas and received her MFA at James Madison University, has taught art at Soka since 2019 and permanently moved to California in 2020, just around the time that the pandemic hit. In “River Deep-Mountain High,” the viewer is introduced a summation of Pearce’s vivid practice pre-and post-COVID.

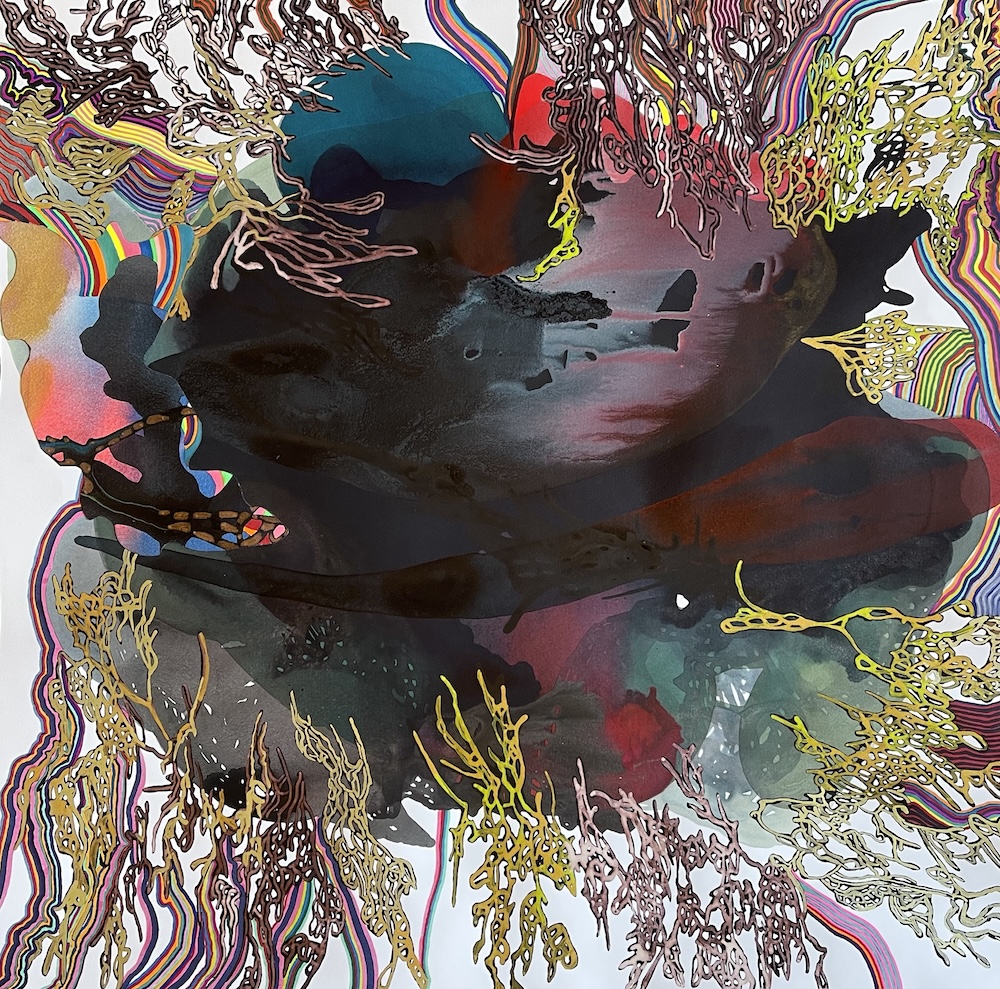

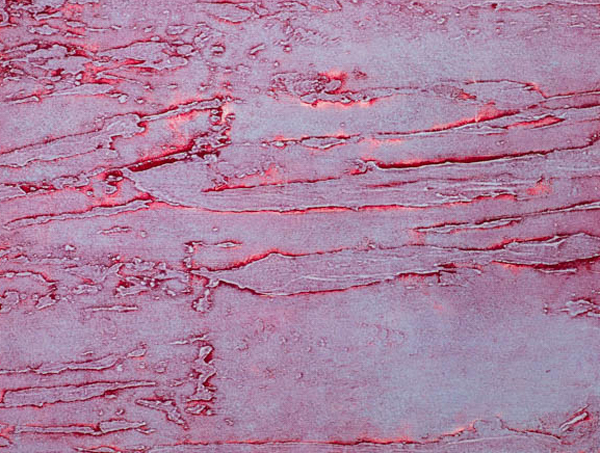

Blue, here, is a consistent color, perhaps because Pearce’s university is close to Aliso Beach, a turquoise stretch of the Pacific that was largely empty of people during the most intense periods of the pandemic. This influence is felt in Icarus/Blue Sea (2024), where Pearce has fashioned a massive, swirling work out of cut paper, inks and kaleidoscopic acrylics, assembling these individual painted pieces of papier collé over entire walls of the Founders Gallery until they form hyperreal and amorphous shapes. These swoop across the eye like a flock of birds—or are we looking instead at a swarm of iridescent insects? A tidal wave? Flying dolphins? When enveloped by Pearce’s flowing, flying blue-green-pink-orange-black atmosphere, I felt my heart beating a little harder. It seemed I had entered a strange Eden that existed in a pristine and hallucinatory state—which is not only a reflection on the longing for a more perfect world that struck so many people c. 2020, but also the clear, smogless air that SoCal momentarily “enjoyed” during that weird, grief-struck spring.

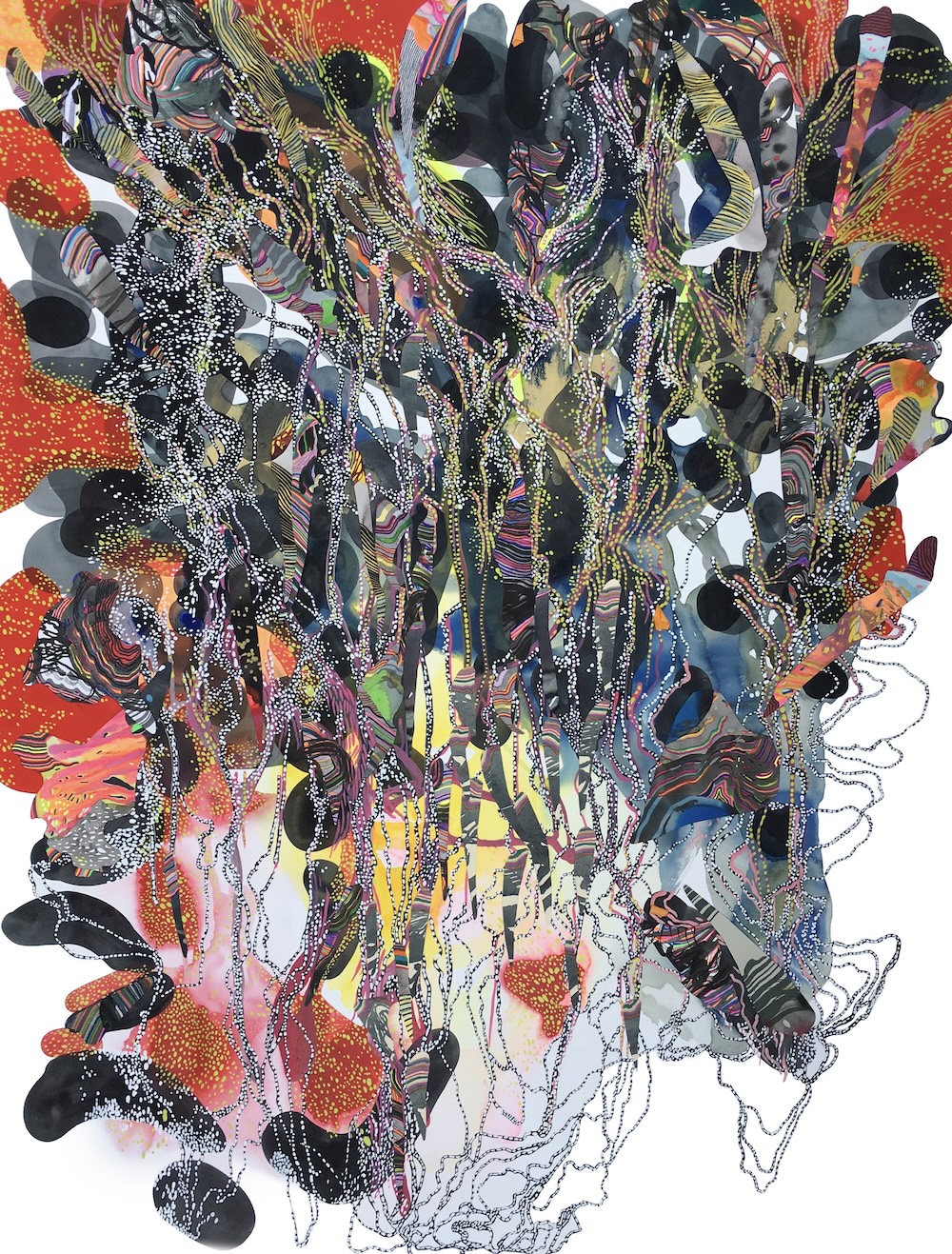

Moonlit High Tide, 2023, Ink, acrylic, collage on paper, 50″ x 38″, 2023 This bracing effect is conveyed in Pearce’s other works, which are contained in frames. Such is the case, for example, in Tidal Exit (2023), where Pearce creates a Day-Glo abstract form that could be a mussel bed, an oil spill or roving school of biofluorescent fish. Moonlight High Tide (2023) is a study of sap greens, moss, that dark-black green of magnolia leaves, indigos. and slices of peach and dandelion, evoking a tidal pool churning with amphibious life. San Clemente Gloaming (2023) offers another study in color and multiplicity: Anchored by bright fuchsia, and laced with bitter orange, black, burgundy, mint and tangerine, the collage does not offer the eye a place to rest, but insists on its own abundance, like cell division, birth, or any other struggle for life.

In April, I tracked down Pearce to ask her about her treatment of color, her place in the colorist practice, and the significance of her latest show. She spoke to me between teaching her classes at Soka, where the semester is beginning to wind down in preparation for the summer break.

Icarus / Blue Sea, Ink, acrylic and pen on paper, 2024 XMM: Your paintings and collages have such an acute sense of tone, shade, and color intensity. They’re reminiscent of the natural world but also take part in a contemporary conversation about the meaning of color in today’s society. Why did you decide to make color such an important part of your work?

AAP: Color for me represents resilience; a life force and ultimate joy in the face of the opacity regarding the natural world. I think a great deal about the differences between mediated color and analog color and the tethers to memory, place, people, time of day, and so on. For example, I will choose pink and green because it flings me back to age 17 and seeing someone in OP green shorts with a pink shirt. Color is what drives the emotion that I hope to invoke in my work.Which painters have influenced your approach to color? Did you cut your teeth on Fauvism when you were young? Did you wander into a room of Rothkos at the Museum of Modern Art? Did the Helen Frankenthaler bug bite you?

All of them and more. I like Frida Kahlo and Henri Julien Félix Rousseau and the colors they used to create jungles. While trying to remember my first experiences with color in the context of art, the first and most impactful experience I had was when I was five years and encountered Aboriginal bark paintings located in an apartment loft apartment in Lawrence, Kansas.

Super Hot Heavy, 2020, ink, acrylic and collage on paper, 38″ x 50″

2020Your work seems to have an environmental focus—it’s made doubly apparent by some of the titles of your works. Are you celebrating a nature that has passed, or are you fighting for a future that you refuse to give up on?

Both. Nature is almost like a deity to me, and I seek to observe and admire natural processes in my work; the past, present, and future. I absolutely refuse to give up on the natural world; in nature things die, things evolve, and wonderful new things are discovered.What’s your process like?

I wake early and answer emails from bed where my fine husband delivers coffee. Close the computer and my eyes for a moment and wander around a daydream about the work I left the night before. Unless I am teaching, traveling, or attending a meeting, I paint daily, and I love it.

Spider, 2021, Ink and acrylic on paper, 25″ x25″ Tell us about your journey to “River Deep-Mountain High:” What were you grappling with when making the work that is presented in the show? How were you able to translate the difficulties of the pandemic to such a large space as the Founders Gallery? Also, what spaces informed the work that occupies the show? Did you do research? Did you travel? Did you journal?

The works in the exhibition were started months prior to the pandemic and continued from 2019 – 2022. The world was tumultuous on myriad social levels and by the time the pandemic was in full swing, my life simply rotated between home, the Soka University of America campus and multiple trips the ocean. I treated this time, the newness of the geography and the environment, and regular communion on the campus with animals (deer, skunks, rabbits, owls, red-tailed hawks, coyotes, bobcats, voles, snails and praying mantis) as unique and special. I had to treat it this way because there was no other real option. I tried to make work that was reflective of the actual earth taking a rest and attempted to celebrate other forms of life, such as plants and animals thriving, who perhaps found themselves enjoying newly-found quiet and a bit less pollution.Where you do you get your ideas for paintings? Do you borrow from your life experience? Or are you inspired by your readings? Do you overhear a conversation or listen to the sound of someone laughing and imagine scenes in your head? Or is the process more mysterious, less connected to language?

My ideas are organic and are reminiscent of plants growing between the cracks of a stone path, they appear as small green shoots and evolve. Collecting and observing, experiences layer on one another and continue shape-shifting and re-settling as new ones are acquired.

Tidal Exit, 2023,

Ink, acrylic, collage on paper, 50′ x 64″Describe your practice of liberating the art from the frame and allowing it to travel over the walls. In some ways, this reminds me of the strengths of set design, which create a world that viewers or actors inhabit. What kind of different relationship can viewers have with art when they are not just looking at a framed picture but rather at an atmosphere that is encircling them?

We did not simply step into nature but rather that we came from nature. We humans have fully adopted the idea that we are somehow divorced or unconnected from nature, and that we sit atop mother nature as if we are some unrelated entity, but this is untrue. I hope that liberating the artwork from the frame and allowing it to froth around the audience who see and experience it will rekindle our connection to the natural world.This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

https://www.soka.edu/founders-gallery

Through September 12, 2024 -

Reconnoiter: Carmina Escobar

Carmina Escobar is an extreme vocalist with an active teaching practice. Born in Mexico and based in Los Angeles, Escobar investigates emotions, states of alienation, and the possibilities of interpersonal connection through voice performances that challenge our understandings of musicality, gender, queerness, race, and the foundations of human communication. Her new project with Micaela Tobin, HOWL SPACE, is a virtual hub offering individualized teaching sessions, workshops, and salons. Beginning in October, HOWL SPACE’S pedagogical project will include virtual round tables with “voice Argonauts” Dorian Wood, Du Yun, El Sancha and Sean Griffin.

You work with “extreme voice” in projects such as Fiesta Perpetua!, a performance launched in 2018, which saw you floating in a raft in the Echo Park Lake and singing otherworldly songs. How is extreme voice so necessary in this political moment?

An extreme voice moves against the status quo. In this moment, it is necessary for our voices to challenge social and political constructions, to break them down or reshape them in order to shift our reality. Our voice asserts us in the world, enables us to project ourselves in it, and expresses our essence in being. Our voices in extreme decibels can join in a scream, proclaim through art, and create avenues for survival, change and agency.

There is a great muteness surrounding the pandemic. How does voice travel across the virus-related silences?

This state of constant lockdown has been a reckoning with ourselves and the power structures we live in. In between the loss, uncertainty, anxiety, and isolation, a blessing can emerge; our inner voice as a tiny dot in the background of the unconscious becomes louder and louder. We are forced to listen to it, to pay attention. I hold on to this state, to listen to my own voice, to learn from the silence which is not silence.

Photo by Sean Deyoe. How is teaching a part of your art practice?

A radical pedagogy of the voice investigates not only the physical mechanics of its production, but also its ancestral trace. In our pedagogy, Micaela and I seek to understand the voice’s multiple possibilities by facilitating a space for its discovery and investigation. A radical pedagogy of the voice is also a tool to understand our world, to have agency in it, to express ourselves through art.

In your workshops and teaching sessions, how will we learn how to engage our voice? Is the end goal personal, spiritual, artistic, political?

The voice is a connecting thread across our communities and a tool to know ourselves. The goal of the lessons and workshops is to release the potential of your voice. When you come to understand your voice, you not only activate your sense of self but can also understand your own voice in your community. In HOWL SPACE we will investigate how your voice can aid your self-affirmation, offer therapeutic tools and be an instrument of liberation.

HOWL SPACE’S schedule of events and opportunities for registration, and info are available on their website: https://www.howlspace.com/. Follow them on Instagram @howlspace.

-

“Path” to Anne Austin Pearce

The collage-paintings of Anne Austin Pearce are unabashedly beautiful. Born, raised and educated in Lawrence, Kansas, Pearce was associate professor of art at Missouri’s Rockhurst University until this year, when she assumed an associate professorship of studio art at Soka University, in Aliso Viejo. From her base in Orange County, she generates complex and hue-drenched phantasmagoria that are the culmination of her 34-year-long career in the arts. Beginning in June, Pearce began to display these works in her exuberant show, “Path,” which is now visible online at the Sherry Leedy gallery in Kansas City.

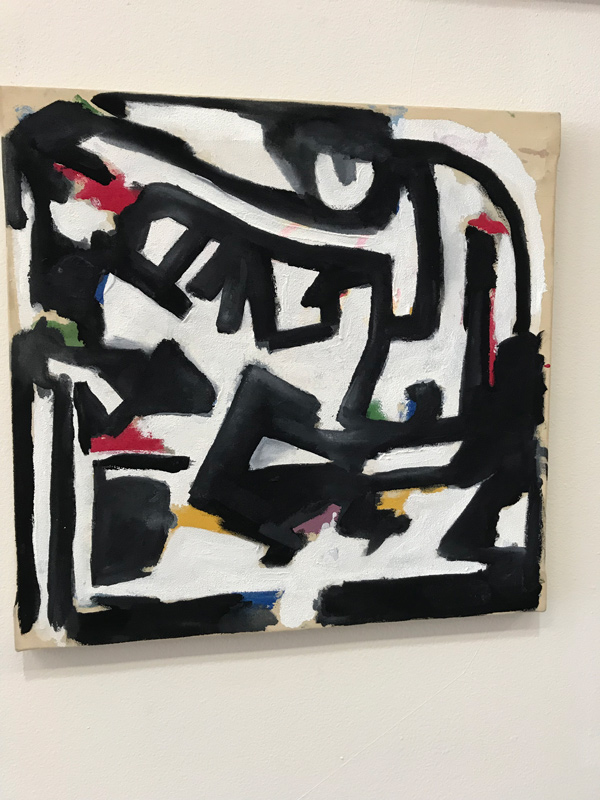

Anne Austin Pearce, Path: Hanged Shafts of Light, 2020 In many of “Path’s” ink-and-acrylic works on paper, Pearce stains and tints paper cut-outs and then assembles them into layered composites that resemble floral and faunal artifacts. Pearce claims an influence from Julie Mehretu, among others, and Mehretu’s whirligigging atmospheres do come to mind as one examines, say, Black, Wet, Stones (2020), a primarily black-and-yellow explosion of kinetic fronds and polka dots that resembles both a panther running through the forest and a galaxy being born. Pearce allows that she hit upon her collage practice when she began to use discarded acrylics as raw materials for fresh paintings: “I’d cut apart older works and collage the pieces into new work as a means to both understand and respond to hyper-felt feelings,” she says. “A small part of one painting becomes a mark within a bigger painting, worlds inside worlds.” This description of her method evokes yet other female artists, such as the great Lee Krasner, who began to furiously shred apart her drawings and remake them into collages after Jackson Pollock died.

Anne Austin Pearce, Path: Well Worth Waiting, 2020 Pearce’s catharsis strikes the viewer in Well Worth Waiting (2020), which has a huge tulip, or heart, or mitochondria flourishing at its center. Tie-dyed eggs or snake-heads crawl up the pink ascent as if it were a mountain, and then spume fuzzy peanuts, scraps of flannel shirts, and gold-dusted black holes. Similarly, in Honeyed Beach (2020), a cosmos of glittering kelp and jellyfish morphs into pieces of sky and patches of ancient maps; the viewer is mesmerized as she tries to trace a familiar shape – is this ocher blob a guinea pig, or a sunspot? – until she realizes that Pearce has merged earth’s elements in an ecstatic union.Pearce’s passions seem ecological, such as in First Plunged in Firefly (2020), where spotted clouds fuse with brightly striped tentacles, and a cerulean, oceanic swell pivots into a grassy savannah – or is it a mysterious calligraphy? Hers is an ambition to see relations between earth and sky, animal and human, which recalls also the reveries of Agnes Martin. For those feeling confused and sad right now, Path does not, at first, seem to offer political commentary, or observations of our current traumas and spirals. Yet, within the intensity of her colors and their combinations, Pearce does demand recognition of the essential, though sometimes invisible, connections between nature and its wary inhabitants.

Anne Austin Pearce, Path: Fist Plunged in Firefly, 2020 Anne Austin Pearce, Path, at Sherry Leedy Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri

June 4-August 22, 2020, and online at https://sherryleedy.com/main/artists/anne-austin-pearce/

-

LACMA: : Mary Corse: A Survey in Light

Los Angeles-based artist Mary Corse is known as one of the few women involved in the 1960s and 1970s West Coast Light and Space Movement, but in her later incarnations, she should also be known for creating a bridge between the “action painting” of Jackson Pollock and minimalism. In her spectral, invigorating retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, viewers are treated to the arc of her obsession with light.

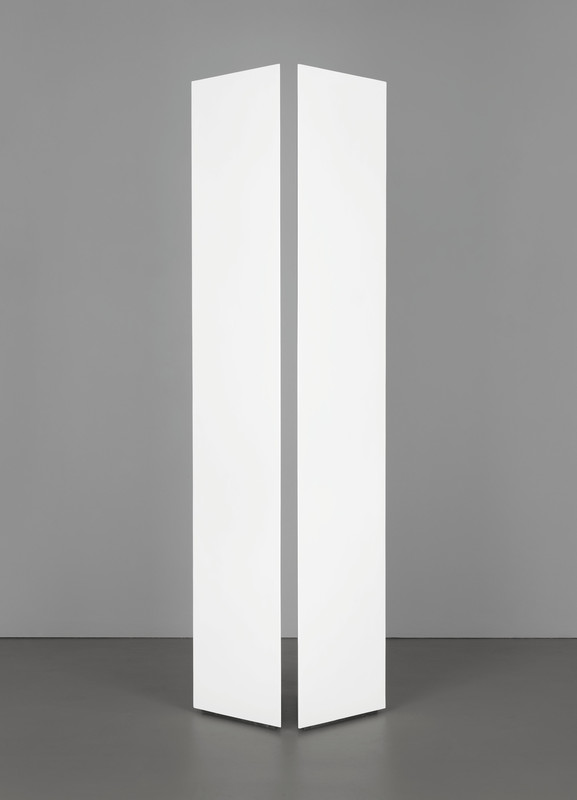

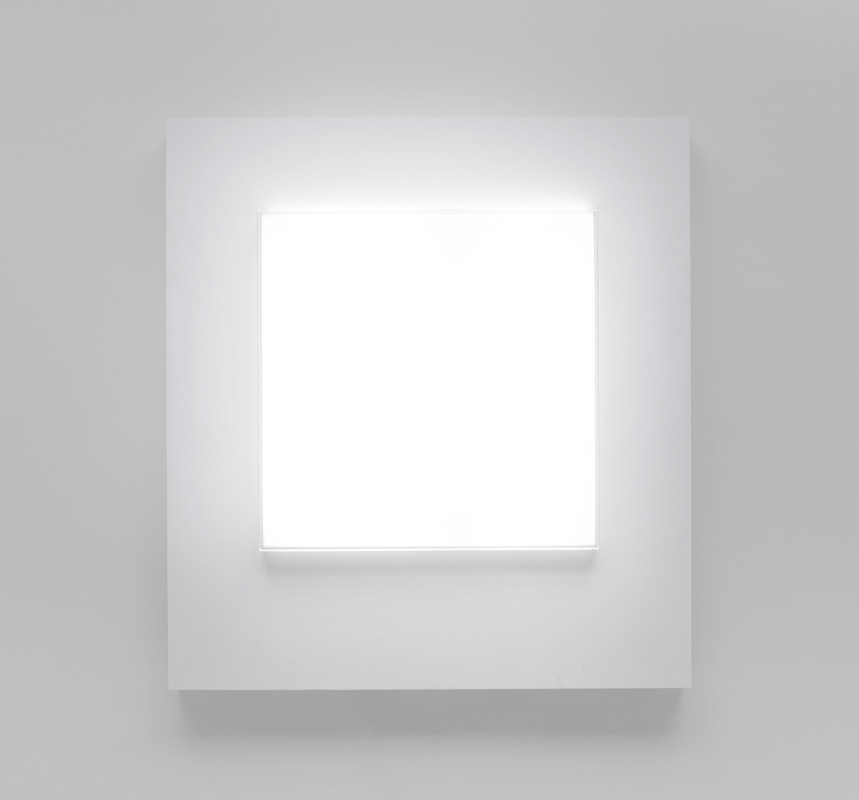

Mary Corse, Untitled (Two Triangular Columns), (1965), two parts: 92 × 18 1/8 × 18 1/8 in. and 92 × 18 1/8 × 18 in., acrylic on wood and plexiglass. Courtesy of Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. In the 1960s and 1970s, fellow Light and Space artists Doug Wheeler and Robert Irwin used lighting elements to create”light paintings” in order to challenge viewers’ perceptions by immersing them in destabilizing luminosity – e.g., Wheeler’s SA MI DW SM 2 75 (1975), which engulfs the observer in glowing lilac, or Irwin’s 1971 Slant/Light/Volume, where a heavenly brightness rolls toward the viewer like a wave. Similarly, Corse built her early work Untitled (White Light Series) (1968) out of plexiglass, fluorescent tubing, and acrylic. Viewers who approach the piece, which LACMA has installed in a darkened nook, will be dazzled by this square of pure white radiance that looks like a smartwatch face set on stun. But later, Corse returned to paint on canvas.

Mary Corse, Untitled (White Light Series), (1966), 72 × 66 × 11 in., fluorescent light, plexiglass, and acrylic on wood. Courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York At the same time, she grew fascinated less by the idea of imposing new perceptions on her audience than creating opportunities for them to craft their own visions by deciding how and where to stand in relation to her paintings: In her stunning Untitled (Black Light Painting) (1975), Corse employed tiny metal flakes and her famous glass microspheres to conjure a huge black totem that emits twinkling star-beams from different coordinates as the viewer sways back and forth in front of the canvas

Mary Corse, Untitled (Black Light Painting), 1975, acrylic squares, glass microspheres, and acrylic on canvas, 108 × 108 in., collection of Sangbeom Kim and Sunjung Kim, © Mary Corse, photograph by Flying Studio In her knockout Untitled (White Inner Band, Beveled) (2011), she painted huge rectangles of microsphere-embedded silver paint, which flash and recede like the ocean’s tide as the visitor walks along its length. The “action” of creating different perceptions is not the artist’s tour de force; in Corse’s work, it’s triggered by the viewer’s own election and position.

-

Hot Summer in the City

Summer festivities abound in the warmer weather. There’s New York’s Shakespeare in the Park, the Pitchfork Music Festival in Chicago, and Cinespia Cemetery Screenings at LA’s own Hollywood Forever. Museums are no exceptions putting on events. LACMA used to host summer jazz fests. The Hammer hosts dance parties. In the last few years, The Broad took advantage of this beach-season custom. From 2016 to 2018, director of audience engagement Ed Patuto, along with curators such as James Spooner and Brandon Stosuy, allowed a host of iconoclastic artists to run wild through the museum’s pristine halls. These events were deemed “(Non)objective Summer Happenings.”

“Happenings” first appeared on the art scene in 1963, when Allan Kaprow held an anarchic New Jersey–based “Tree Happening” that he hoped would abolish the “artist-audience” divide. The Broad’s update of this fest worked to dismantle gender barriers through the inclusion of queer and nonbinary artists. Still, it didn’t seem likely that the Broad could achieve its radical goals, since the museum is a luxury behemoth riddled with disciplinary mandates. Happeners would arrive at the Broad’s scary, Death Star-esque building knowing that if they crossed the artist-audience divide by hugging a Murakami they would be arrested.

Allan Kaprow, instructions for “Tree Happening,” 1963. But Ed Patuto pulled off great shows. When reached by telephone, he explained that the Happenings were inspired by his life in New York circa 1970s and 1980s. “Back then you’d go to gallery shows and performances in lofts and then go hear music,” he said. “It’s not like any of these things were separated from each other, and the core of [the Broad’s] collection is a lot of art from the ’80s created in LA and New York. I wanted to give people a flavor of what was the environment that helped produce all of that artwork that they’re seeing on the walls of the museum.”

One of the finest examples of Broad hybridization occurred in June 2016, when the LA-based Mutant Salon collective occupied its Oculus Gallery. Here, Happeners encountered a beauty parlor filled with gender “mutants” who fashioned themselves out of merkins, makeup and pantyhose play. Just as fantastic was Brontez Purnell’s August, 2016 action, when Purnell skateboarded around the Broad’s foyer dressed in BVDs and threw toilet paper rolls at the audience while accompanied by a Ronald Reagan soundtrack.

Young Joon Kwak, “Mutating Stakes” (detail view), 2014. Photo: Heather Rasmussen. But could anything have been more fun than the Kembra Phaler’s concert the following year? In June, 2017, members of Phaler’s art band, The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, jammed around the Broad dressed like troll dolls, while inserting reversed crucifixes into their orifices and screaming tunes like “Ghost Boyfriend.” Later that August, radical Catholic Linda Mary Monsato appeared in the lobby dressed like Mother Teresa. Happeners approached Monsato looking for blessings, which she administered by yanking them back and forth by the neck while singing “Lullaby and Goodnight.”

“I think that what it did is it put LA artists in a context with other artists from here in the U.S. but also internationally,” Patuto said. “I also think that it showed that LA is a place where the community supports greatly innovative programming.”

Kembra Pfahler backstage at the Broad Museum’s “Summer Happening” series, 2017. Photo: Steve Appleford. The Broad continues to host vivid summer programs, and this year expanded its repertoire to harmonize with its blockbuster show Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983. It held a series of jazz concerts (one of them curated by Quincy Jones) meant to complement the thrilling range of artists featured in the exhibit. Music had always been part of the Broad’s summer scene, and the Soul concerts upped the ante with galvanic performances by artists such as saxophonist Roscoe Mitchel, pianist Brett Carson, and the galactically talented vocalist and dancer Eryn Allen Kane. With its burgeoning tradition of hot-weather entertainments that merge politics, song, movement, sculpture, video and painting, we will be excited to see what the Broad plans next summer.

-

Cayetano Ferrer

“Many years ago,” Maggie Nelson writes in her memoir, The Argonauts, “[the poet Anne] Carson gave a lecture …at which she introduced (to me) the concept of leaving a space empty so that God could rush in …” Nelson writes that she “fastened” to the idea, which she thought seemed like “the thing that [could] keep you going, in heart or art, for years.”

The notion of “leaving a space empty” for holiness to come flooding in is a beguiling one, but it also contains a description of human consciousness as abundant and crowding. Are people (or poets) so world-conquering that we can punch out a cubby for the divine? Or, instead, do the gods pummel down upon us in cascades, so that all we can do is construct crushable edifices from which we peer out, maybe trembling?

The artist Cayetano Ferrer, known for his spare and suggestive installations, offers us the second reading of spirituality or cognition in his radiant show at Commonwealth & Council, “Memory Screen.” Entering into Commonwealth’s joyous atmosphere (presided over by the welcoming Young Chung), the viewer first encounters Mmry Scrn (2019), a door built out of reclaimed wooden furniture parts, newly molded fixtures and negative space. The screen’s carved dowels create the thinnest frame for the world, and looks constructed out of calligraphy. Mmry Scrn faces three skeletons of stained glass windows (Window, 2019), which Ferrer placed in a wall halfway across the gallery. He formed these apertures out of a combination of epoxy and wire that resembles the lead bones typically supporting tinted windows in cathedrals. Modeled on actual stained glass rosettes, these borrow their colored lights from a separate room, which he irradiated with tones of orange, blue and red. The viewer can stand at the farthest edge of the clearance, looking between the lacunae of the screen, to the windows’ jewel-toned mesh, and into the deeply-lit chamber beyond.

Cayetano Ferrer, Window (2019), courtesy Commonwealth & Council. What’s there? Moving past the windows, we find what appears to be a grand structure made of floral reliefs, Greek symbols, chains and ropes. It is a wall—no, a gate (Gates of Hell Movie Set [1:5 scale], 2019)—as it contains at its center a small door, too low even for a child to enter without ducking. Unlike the frangible screen and windows, this object (from a Warner Brother’s mold) seems more like Carson’s perception, as it only offers God a little crawlspace. But when you go behind the barrier, you see the hell gate is made of thin plywood.

That Ferrer can enchant us with our own frailty—the slender huts that we shelter under, the breakable spectacles out of which we peer at existence—offers happiness in the space where Carson says God lurks. His vision of the human mind contains a consolation greater, I think, than the one that thrilled Nelson, since it finds beauty in the small and contingent, rather than aggrandizement.

-

Carolina Maki Kitagawa at Eastside International

When we withdraw from other people out of choice, we call the result privacy. When someone forces us into seclusion, it’s kidnapping. The artist Carolina Maki Kitagawa’s new show at Eastside International Los Angeles, “Story’s End No. 1 // Continúa El Cuento Nº. 1” plays with the blurry border between these two truisms. In Eastside’s spare, idea-filled space in DTLA, Kitagawa interacts with her sculptures, paintings, and video in ways that telegraph the confusions of living in a surveillance society whose economy is driven in part by walls and human capture.

In Homage to Harry Gamboa Jr., Kitagawa constructs a collage out of a photograph that seems to be of a person (Gamboa?) wearing a crown and standing next to a palm tree: A viewer can’t see the image, though, because it’s shielded by a block of blue wood. The work is also affixed with a security camera that glares at spectators while they try to peer around the obstruction to see what lies beneath. A similar conceit drives Homage to Selena, where a photograph of one woman holding another woman’s arm (perhaps one of these is the singer Selena Quintanilla?) is barricaded by a rectangular red block of wood.

Kitagawa’s quirky aesthetic also infuses a small sculpture that looks like Gumby (it is a mock-up of a race-obliterating costume that Eddie Murphy wore on Saturday Night Live in the 1980’s) standing next to a brown handkerchief that drapes over yet another security camera. Beneath this assemblage presides a drawing of Mickey Mouse with a muscular wrestler’s body that Kitagawa’s nephew, Kazuo, drew for her. In a recessed area, we see a multicolor video spliced together from the surveillance footage.

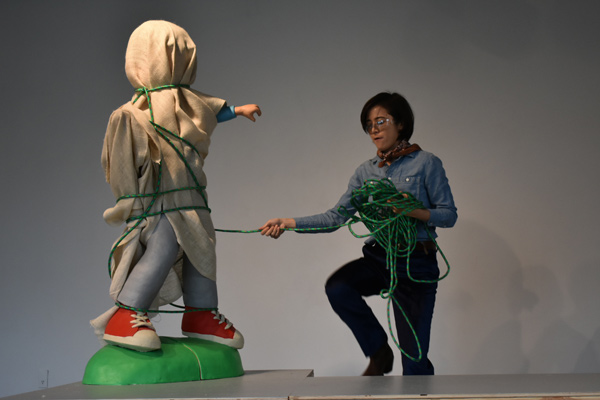

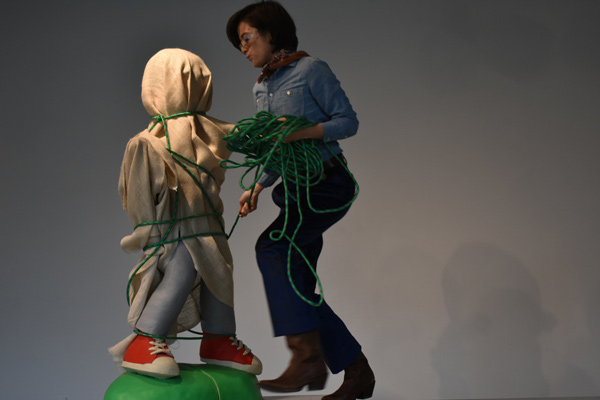

What does it all mean? The interplay between hide and seek, retreat and capture, finds even more beguiling expression in Kitagawa’s three-part performance. On February 16, she began this trilogy by introducing two large sculptures of boys in the gallery: The large, wood-and-paint figures (one of which is modeled after her nephew) stand before each other as if about to fight—Kitagawa messages the mood of violence by outfitting one figure in golden boxing gloves.

On Saturday, March 2, Kitagawa began the second part of her epic by performing a mummery wherein she put on safety glasses and covered both figures in linen tarps. She smothered them in the fabric and then began to tie them up with green rope, over and over again. The linen went over the figures’ heads and the ropes fettered them at their throats, chests, and hips.

When she first cast the cloaks over the boys, the gesture seemed tender; but then dread crept in as she began to imprison them. Kitagawa did not speak during her action, but stamped her feet as she circled her sculptures, muzzling them and binding them until she almost completely hid them from view.

Was she protecting the boys from the brutality of the world with her strange shields? Was she strangling and suffocating them? Both. Her bizarre, ingenious, and elegantly minimalist pantomime described the state we find ourselves in now: We would like to find sanctuary away from the savagery around us, but even as we try to retreat, we find ourselves stepping back into enforced silence and prisons.

On March 30, Kitagawa will hold her last of the exhibition’s performances at Eastside International.

Carolina Maki Kitagawa, “Story’s End No. 1 // Continúa El Cuento Nº. 1,” February 16 – March 30, 2019, at Eastside International Los Angeles, 602 Moulton Avenue, Los Angeles, CA, 90031. www.eastsideinternational.com

-

The Empathetic Encausticisms of Pamela Smith Hudson

In her Culver City studio on a late summer afternoon, encaustic painter, printmaker and educator Pamela Smith Hudson revealed the origins of her vocation as a “materials artist” dedicated to exploring the potentials of paint, clay, print and wax: “My dad was a cement mason,” she said, while surrounded by her liquid-looking charcoal, teal, rose and cream-white canvases. “Dad worked on the federal building,” she emphasized. “So cement, plaster and wood were always around the house. Also, my mom was an artist, or had been.”

With a landscape-oriented show that stretched from early spring through the waning days of summer at the California African American Museum (the exquisitely curated Charting the Terrain, which also featured works by Eric Mack), and a swiftly mounting reputation for taking encaustic painting to new heights, Hudson has become a new luminary on the Los Angeles arts circuit. For most of her adult life, though, she has produced work quietly in her studio when able to find the time. Until recently, she juggled painting, raising her children with her husband, working as an arts supplies representative for major companies, and teaching at Otis College of Art and Design and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

City of Angels I, (2017). Monotype on clay panel (1 of 8). 9 x 22 inches But three years ago, Hudson’s mother grew ill and Hudson realized that she wanted to bring her art out into the world.

“My mom stopped painting to take care of the children, and I never knew she was a painter until we went to a Lee Krasner [show]. We were looking at the paintings, and she told me that she had been an artist. Later, after she got sick, there was a connection between her being in hospice and making this journey of leaving her body that made it okay [for me to focus more on my art]. I realized I had been of service to my family—family’s first—but I decided to have an exhibiting career.”

Ever, Never After (2016-17). Cold wax mixed media on canvas. 48 x 72 inches. While Hudson only began showing in earnest in 2015, she has worked in encaustic since the 1990s: That’s when she met Daniel Freeman, the printer at the Gemini G.E.L. print shop and publishing house. Freeman noted a resemblance between Hudson’s practice and that of Jasper Johns, with whom he had collaborated. Freeman encouraged Hudson to study Johns’ methods: a direction that led to her immersion in the ancient practice of mixing pigments with hot beeswax to create a variety of effects. Used by artisans since the era of ancient Egypt (important examples include the Fayum mummy portraits, c. 100–300 CE), encaustic can be carved, smoothed like lacquer, or built up like putty. Johns reinvigorated the method with his famous painting Flag (1954–55), mixing wax with strips of newspaper to create an uncanny and iconic image. Hudson found herself inspired by his example.

Eric Dolphy’s House 1/2 (2010). Acrylic mixed media on panel (2 panels). 16 x 20 inches. Photograph: Jim McHugh. “Wax dries so fast,” Hudson said, showing a visitor a radiant and rippling graphite panel. “That’s why you can get layers in between layers, and you can see between the translucency. It’s like in music, that silence that’s in between the notes, in between spaces, that you want to capture. A lot of my work is about revealing and unrevealing, and then covering up again. It’s a back and forth.”

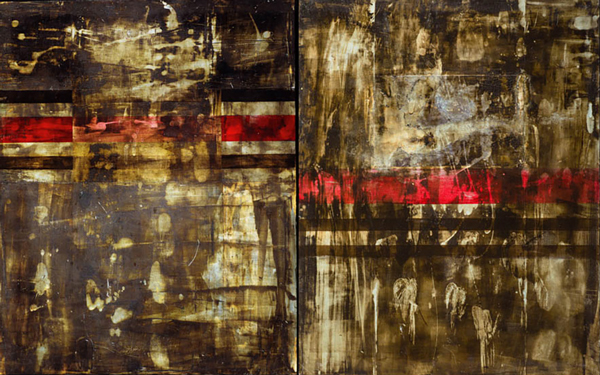

As Hudson talks about her practice, she often circles back to the revelations that occur in music. Her longtime passion for jazz inspired one of the pieces that starred in the CAAM show: Eric Dolphy’s House 1/2 (2010) is a beautiful burned-brown mixed-media diptych with a strip of fire-engine red cutting through a charred-looking landscape. This work is a meditation on the Los Angeles home of American jazz great Dolphy, which Dolphy had used as a studio. It was turned into a community center after his death, but the house then burned in the 1992 uprisings triggered by the acquittal of four police officers filmed brutally beating Rodney King.

“It was such an important historical site,” Hudson said. “[John] Coltrane recorded there, and so did [Charles] Mingus, and Miles Davis was coming by. And then after Dolphy died [the house was destroyed]. So the painting’s a memorial piece.”

Roam (2015). Encaustic on panel. 5 x 7 inches. Photograph: Jim McHugh. In the studio, the LA sunlight glimmered across gray-black panels that looked like the roiling ocean and a lichen-dappled forest floor. A pink canvas revealed a mottled rose that resembled tender flesh. One round painting glowed cerulean, like an unharmed planet. In all of these works, materiality becomes a strategy for cementing life and history into durable forms, even as they slip away on account of catastrophes both natural and human-made.

Hudson reached down and grazed her fingers gently over the circular blue painting.

“The translucent layers of encaustic investigate these systems of things that were there before, and things that will exist, and things that keep moving forward,” she said, smilingly slightly. “There’s a philosophical aspect as well.”

-

ARTXFOOD: A Case of Cross-Cultural Indigestion

When is a painting high art, and when is it just nice wallpaper?

On May 10, I learned the answer to this question when attending ARTXFOOD’s inaugural art-themed dinner, Hallowed Ground. ARTXFOOD is produced by ArtCubed Los Angeles, which hosted a “part salon, part summit happening” at Goya Studios. The event involved eating a fancy dinner designed by celebrity chef Richard Blais while surrounded by the luminous paintings and sculptures of LA-based artist Greg Ito.

Greg Ito (left) and chef Richard Blais. Art dinners, as it so happens, are a thing—though in a weird, half-formed way. If readers do a Google search, they will discover similar centaurs in the forms of “Transparent Platform,” a production company that in 2016 held “a live art dining soirée” at London’s L’Escargot Members’ Club, inviting consumers to eat while watching artists paint a nude transgender model. And in Moss, Norway, one may nibble asparagus salad while staring at some of Edvard Munch’s metaphysical horrors at Refsnes Gods, an “art hotel” filled with Munchalia.

ARTXFOOD’s ambiance held up well to the international food-art world’s freewheeling mise-en-scène. Goya’s tasteful space was irradiated by Ito’s pop-colored show, which touched on fairy tales, family communion, and time: On the floor gleamed a big ceramic prince-frog and a parade of bright black-and-white swans. One wall featured a painting that was bifurcated into black-and-pink sections, revealing graceful hands caressing themselves amidst treetops. A triptych showed one pink hand and one brown hand reaching for the other, and two superimposed faces leaning in for a kiss.

After allowing for about 20 art-appreciation minutes, however, it was time to eat. Amiable docents led guests into an inner sanctum, the “ArtCube:” This little house held more of Ito’s art, as well as dinner tables. My favorite of Ito’s paintings presented a view through a window that revealed a striking strip of turquoise and a sparkly flame flickering among shadows… but I sort of forgot the artwork because I was eating bourbon-soaked cherries, and then came some weird-tasting Hawaiian bread doused in tepid bone marrow, and then a nice mash of chicken oysters folded in a Yuzu leaf. An insanely sweet “unicorn soup” followed, blending together sea urchin, corn and a pun. Next came black duck and onyx carrots glazed with pomegranate syrup and… charcoal dust? The latter dish excitingly recalled the noir libido-mourning feast in Joris-Karl Huysmans’ À rebours (1884); but the duck was overcooked. For dessert I despairingly licked a plate of purple ice cream, white icing, white bread and an intentional smattering of ants.

Food being served. The goal of this hybrid spectacle appeared initially to hearken back to older, even ancient, synesthetic practices. High points in this history were reached by former painter and Provençal cuisine maître Richard Olney, and the dinners conjured by Alice B. Toklas for Gertrude Stein and friends. Though perhaps even these heroes were mere epigones of the ancient Romans: The 1st-century Pompeiian Villa of Mysteries was a safe house where elite women were trained in ecstatic Dionysian arts, and rested their orgy-exhausted limbs in a dining room (the triclinium) surrounded by ravishing frescoes of Bacchae submitting to the lash.

Dreaming of Bacchae noshing on Toklas’ pot brownies, I regret that in today’s consumerist climate a food-art event inevitably creates a fatal contest, where food will always win. Our culture has cultivated our habits of admiring and critiquing meals. But these practices are not as well supported for the arts. Does one stand before a sculpture for 30 seconds or an hour? Do we like Manet and/or Gronk? With art, there is no bitter, salty, sour or sweet—we have to access mysterious hierarchies to develop our tastes.

Thus, I would rather study Greg Ito’s work without the distractions of antsy ice cream, which nearly converted his great art into the above-mentioned wallpaper. Much depends upon dinner, and, at ARTXFOOD, its undue influence threatened to transform me into a frenzied satyr like George Costanza.

Courtesy of ArtCubed. Some readers may recall George Costanza. He is the rotund enraged one, from Seinfeld. There’s that episode where Costanza gets in trouble with a woman because he tries to multi-platform his senses. Costanza doesn’t try to host a Pompeiian “art dinner” exactly; he wants to have sex and eat a sandwich at the same time. But when he attempts to give his lady deli-pleasure, the lunchmeat gabbles out of his mouth as if he were a zombie. His girlfriend objects by screeching and running away.

The next day, Costanza tells Jerry that he and his girlfriend broke up because he “flew too close to the sun on wings of pastrami”—as did I at ARTXFOOD, though my crashing juggernaut was made of mad aspirations weighed down by fatty bread and sugary soup.

-

Feminist Latinx Performance Art

On Thursday, May 24, the Broad Museum was infiltrated by a coven of four Latinx she-monsters wearing wigs on their faces, jeans tossed around their shoulders, and topless fake-hair onesies. In the Broad’s foyer, they appeared in the midst of a luxuriously-dressed LA crowd. They commenced the action by wandering about aimlessly. They nudged up against the spectator’s bodies. They started crawling on the ground. They tried to put on their jeans, and thrashed around when the pants wouldn’t fit right. They gathered together in a little huddle and sang, louder and louder, until they were screaming and nearly vomiting. Then one of the enchantresses grabbed her jeans and ran up to a wall didactic explaining the Broad’s current blockbuster Jasper Johns retrospective. She flagellated Johns’ name with her pants while the crowd started cheering. After that, all of the women erupted into a frenzy of jeggings-whipping and more floor-writhing.

This was Uruguayan/Brooklynite choreographer luciana achugar’s FEELingpleasuresatisfactioncelebrationholyFORM, the opening act of the Broad’s exciting and continuing En Cuatro Patas (on all fours) program of feminist Latinx performance art. Curated by LA-based performance artist and filmmaker Nao Bustamante and Oakland provocatrix Xandra Ibarra, the happening possessed the astringency of home truths. Bustamante, later appearing before the audience, explained that the theme of the evening was “the corporeality of abjection.” Yet, when the hairy sorceresses had started hyperventilating and droolingly grunting at each other, their gesture seemed like a fair recreation of the conversations I have about DACA abolition and Planned Parenthood defunding with my colleagues at work every morning.

The corporeality of abjection – in other words, “in yo face.” The short videos that provided the show’s second act generated revelations about how unleashed official racism and patriarchal rule-of-lawlessness dismantle women of color’s bodies. Peruvian movement artist Amapola Prada’s film 2014 showed her tied to a fence while wearing a school uniform and a black, eyeless head-sock, and trying to run repeatedly toward the observer. Dominican-American Joiri Minaya, in 2002’s Satisfied, sits in her underwear at a kitchen table and crams fake dead mice in her mouth until she gags. In her undated Binólogo #1 (Nest / Nido), she may be healing herself as she drinks clear water witched from a bird’s nest that she discovers on a naked man’s crotch.

Longstanding collaborators Abigail Severance and Julie Tolentino’s petrifying evidence revealed a woman getting her bottom “cupped” not by a lover but by a handyman affixing glass bulbs all over her hind quarters. Mickey Negron’s coruscating PonerMickeytarme: Ritual de pluma y purificacion (nd) displays Negron with a mustache, tight pectorals, and shapely round bottom. They douse themselves with honey and feathers while standing amid a crowd of churchgoers attending a religious event. The film sways between horror, while women scream at him and seem ready to commit violence, to jubilation, as several people lovingly approach Negron and give them urgent hugs.

Xandra Ibarra’s Fuck My Life appeared constructed around the body abjection thesis: Ibarra is a critical race burlesque performer who makes “spic-tacles” that work to defeat the white gaze, but fail to do so – so, “FML.” Ibarra’s narrative began with a striptease performer waking up in bed makeup-smeared and hosting a Magic Wand between her legs. Her morning’s highlights find her scuttling around her apartment swilling bourbon and peeing before dressing up like a huge golden cockroach and running away. Ibarra’s work laments her inability to create teachable lessons, but her star quality remains so incandescent that her efforts to be corporeally abject fail. Watching her bash lipstick into her face I wondered about the epigenetic utility her kind of glamour distributes – it’s not just beauty; it’s a Marilyn Monroe/Lupe Velez halo that hijacked Ibarra’s dour message and seemed to possess as its greatest purpose the inducement of dangerous scopophiliacs to bow down.

Carmina Escobar’s fabulous Passer embodied not abjection, but nature, the forest, technology, and the cosmos. Escobar, a renowned voice artist, appeared on the Broad’s third floor dressed in red feathers, a black velvet gown, gold shoes, and a necklace with a huge glass pendant that contained balls made of copper twine. She assumed the mantle of Ovid’s Philomela, whose voice was torn away by Tereus and restored by the gods when they transformed her into a nightingale. Escobar’s excellent vocal range ascended to a tinnitus-like pitch, which she modified with a machine so that it echoed back and then distorted into the crashing sounds of computer malfunction. Escobar took out the little copper twine-balls from her pendant and put them in her mouth, unspooling the threads with her fingers. She affixed them to a ceramic mushroom and gave the free ends to audience-members, who all seemed to love what was going on.

After that, Escobar passed out little colored slips of cellophane. She took off her robe, stood before us completely naked, and called upon the people with the cellophane to rub it with their hands. A magical sound like rain fell from the air, combining with the music that had now softened from industrial noise to harmonic convergence. Escobar closed her eyes, raised her hands, and conducted the music made by the cellophane. The ingenuity of this symphony made her a conductor more formidable than Dudamel. And its beauty gave observers the strength to grapple with the deep sadness of the other artists’ work, rather than succumbing to their terrifying message that the current nightmare is actually our waking life and there may be no way out of it.

The Broad’s En Cuatro Patas continues on Thursday, Oct. 11, and Thursday, Nov. 15.

Photographs by Ben Gibbs

-

Beautiful Mutant: Young Joon Kwak

On the evening of June 25, 2016, a group of gorgeous mutants rushed out of The Broad museum and began loving themselves and each other on South Grand Avenue. This band of performers, known collectively as Mutant Salon, is run by the LA-based visionary artist Young Joon Kwak. The collective had assembled at the beginning of the evening inside the Broad’s tiny Oculus Hall, as a part of the summer Happening series. But Kwak and her renegades could not abide by their confinement. Mutant Salon streamed out of the dark, broody Oculus, dashed through the museum’s blue-chip galleries, and ran into the lamplit dazzle of Downtown LA. Wearing little more than makeup, gold boots, wedding veils and bikini tops, the seraphs charged around the entrance of Eli Broad’s luxury spaceship, engaged in a performance that they called “We Make Each Other Beautiful.”

Free Mutant Salon: We Make Each Other Beautiful, 2016. Performance at The Broad, photo by Barak Zemer. “[Working with the Broad] was a learning experience for us,” explained Kwak, who is not only Mutant Salon’s co-organizer (with Marvin Astorga, Sarah Gail Armstrong, Project Rage Queen, and Alli Miller), but also its founder. A Korean-American trans performance artist, rock star and ceramicist, Kwak chatted about the Salon and the rest of her work on a recent Monday afternoon in her Eagle Rock studio, while also allowing a visitor to cuddle her biomorphic sculptures, epoxy paintings and 14-year-old Yorkie named Ms. Tina. Wearing a bronze necklace in the pussy-friendly shape of Baubo, the Greek goddess Demeter’s jester, as well as a fetching military jacket with the words “Rest In Power” embroidered on the back, she described the cognitive dissonance of installing Mutant Salon at the Broad, a site of extreme cultural power and seemingly endless money.

Young Joon Kwak, Mutating Stakes (detail view), 2014; Steel, pigmented plaster, resin, found objects; dimensions variable, photo by Heather Rasmussen, Courtesy of the Artist and Commonwealth & Council. When contemplating Mutant Salon’s election to transgress the borders of the Broad and move into the city streets, it’s critical to remember, “how important [our] community is to the project,” Kwak said, specifying that she works with queer, trans, woman and “POC” [people of color] folks. “We didn’t know that [the Broad’s Happening] would be a $35 event, and that stings, because a lot of us are poor, so we just wanted to make sure the people in our community would be able to come out and participate. We didn’t just want to have the Salon in the Oculus, which is a weird anus of the museum. We wanted to put on the performance for free, too.”

Where I Am My Own Other, Where My Mother Is Me, 2016, detail of live performance collaboration with Kim Ye at the Hammer; photo by Christopher Richmond. Kwak, who just won a Rema Hort Mann Foundation grant and is represented by Commonwealth and Council, initiated Mutant Salon as an itinerant piece of relational and performance art. Mutant Salon is a moveable beauty salon, filled with comfy chairs, dress-up clothes, makeup, soothing unguents, handmade porcelain combs. It is enlivened by a changing cast of performers who interact with each other while applying mascara, donning merkins or braiding their hair in a protest-cum-love-in that exorcises the oppressions of mainstream beauty standards.

The Salon had its genesis in 2012, when Kwak moved to Los Angeles from Chicago to attend USC’s Roski School of Art and Design. Born in Queens, NY, in 1984, and educated in Chicago, Kwak rented an apartment on Olympic and Vermont, but did not feel “safe to get dressed and do makeup” around that area. She began to use her USC studio for self-care, and in the process discovered that she was creating a “safe space” for liberatory dressing. Friends and acquaintances began dropping by and participating, and thus the first stages of Mutant Salon were born.

Mutating Stakes, 2014, steel, pigmented plaster, resin, found objects; dimensions variable, photo by Josh White. The frontier-crossing “mutant,” whom Kwak defines as a person who is “mutable, transformative and hybrid,” is an apt icon for Kwak’s larger oeuvre, which has long challenged binary gender and thinking by adapting materials and ideas into unexpected forms.

In 2010, after receiving her BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and a Humanities MA at the University of Chicago, she combined the elements of yoga, oil, fire, emotional submission, resurrection and ornithology to make (with Anneka Herre) the video Transgenesis II: Dead of Dawn, in which she is cast as an oil-drowned baby bird who is washed clean by a loving if over-controlling mommy. Kwak’s gifts for transformation later found expression in 2013’s Excreted Venus, a photograph that shows her bound, doused in potter’s clay, and posed (it seems to this observer) like the goddess Lakshmi. Was this sculpture? Performance? Her challenges to art categories continued with her handcrafts—as in 2014’s Mutating Stakes, multi-colored and drippingly anthropomorphic painted sculptures made out of steel, plaster, silicone rubber body molds, a wig head, epoxy resin and facial cosmetics. Then in October, 2017, she put on a performance, with Kim Ye, titled Where I Am My Own Other, Where My Mother Is Me, wherein another loving but disturbing mother-lover figure feeds Kwak’s persona a large, deeply pigmented pink cake, which later gets smeared all around her body and onto the floor, in a gesture that seems related to Jackson Pollock’s action paintings as well as Ana Mendieta’s Untitled (Blood Sign #2/Body Tracks) (1979).

Young Joon Kwak & Kim Ye, Where I Am My Own Other, Where My Mother Is Me, 2017; video still, 15 min. 3 sec. Performance is where Kwak brings her mixed mediums and her message of unity most intimately together. Her life as a rock star began with Xina Xurner, the initially Chicago-based band that she started with her partner, Marvin Astorga, in 2011. Xina Xurner, whose name plays on the specter of the diva-hero Tina Turner, set out to deliver “cunty noise-diva-dance anthems that ooze sex, death and decay.” It got its start in underground Windy City clubs, which Kwak notes were most noteworthy for a “punk scene which is also noise-bro-dominated,” but which quickly made space for Xina Xurner’s music. “It was like, we’re doing it for Chicago!” Kwak exclaimed in her studio, describing how the audience would dance and identify along. As Xina Xurner, Kwak wore evening gowns and paraded glorious grooming, and also morphed her voice with the aid of transformers. “I can shift my voice from sounding like a woman to sounding like a little baby, or go really deep, like a man, or more robotic—it’s vocal drag vocal mutation,” she explained, while fiddling with her computer, which soon began emitting operatic disco tunes.

Mutant Salon developed in tandem with Xina Xurner and shares its ethos of civic chaos and love. (As Kwak played songs from Xina’s upcoming album, Queens of the Night, she sang to her interviewer, who began dancing in the studio along with Ms. Tina.) “There’s a lot of dress up and costume [in my work],” Kwak laughed, bouncing to the music. “And we can be covered in trash and look like monsters, but we’re still beautiful, because we make each other beautiful.” She paused for a second, and grew thoughtful, as the February winter light made her Baubo necklace sparkle. “There’s an idea that my friend Gordon Hall—an artist and writer—taught me about. Gordon has this idea about what he calls reparative objectification. We look at each other as objects in profound affirmation, and kind of apart from how objectification is typically dehumanizing. We twist that into something reparative, affirming.” She smiled as Queens of the Night blasted through the studio. “I want the work to be inviting and welcoming, you know? It’s about finding that balance of strangeness, and the ugly, and the monstrous, and the messy.”

EXCLUSIVE Premiere of Xina Xurner’s New Music Video, Gentle.

Gentle is a track from the second full length LP Queens Of The Night, by Xina Xurner (collaboration between Los Angeles-based artist/performer Young Joon Kwak & musician Marvin Astorga), released in April of 2018. Queens Of The Night is a battlecry for the femme destruction of the patriarchy through collective resistance, rage, affirmation, and transformation.

Mutating Stakes, 2014, steel, pigmented plaster, resin, found objects; dimensions variable -

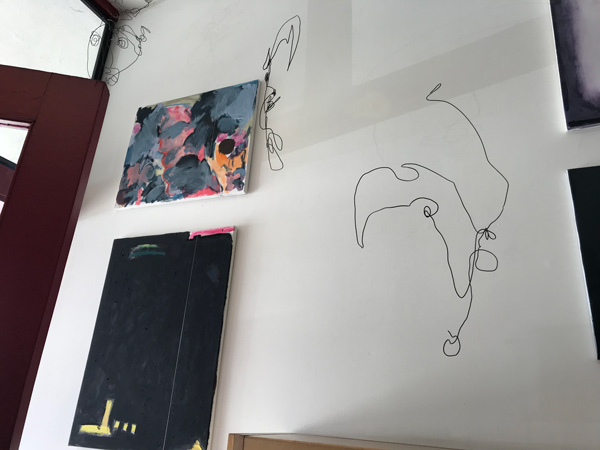

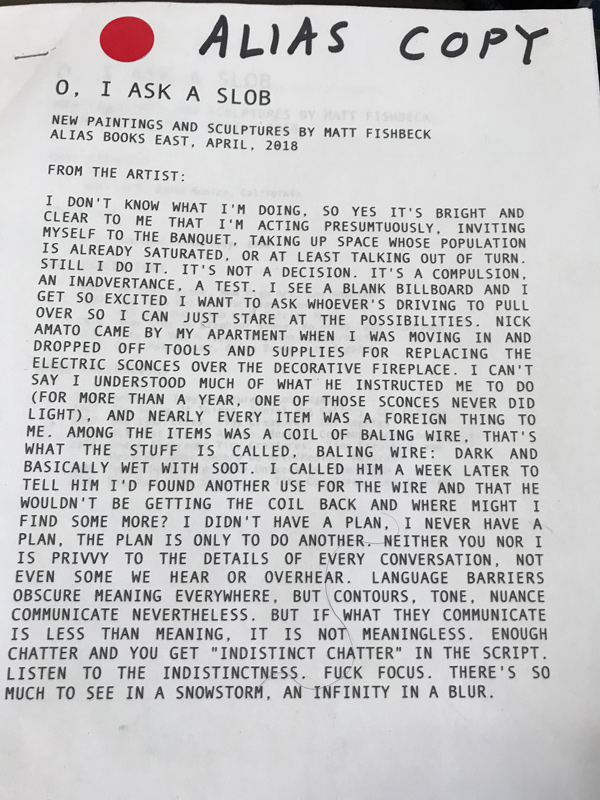

Alias Books East: : Matt Fishbeck

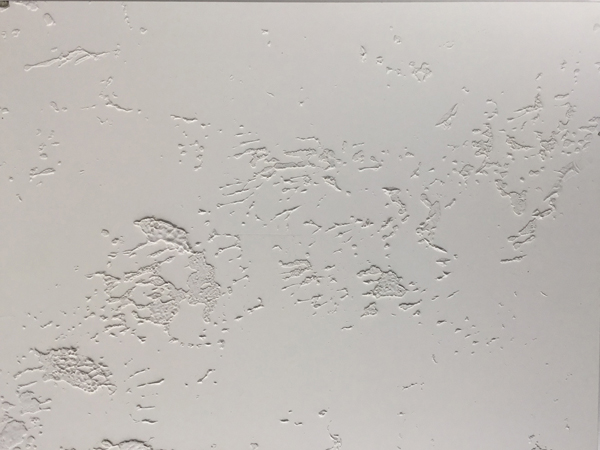

At Alias Books East, in Atwater Village, hangs an unfinished piece of sky. The artist and musician Matt Fishbeck made it by scrabbling a piece of denim-colored stick of oil pastel onto a board. The painting hovers on Alias Books East’s west-facing “art wall” next to a Chihuahua face made out of wire, a black painting with a little wavery white line drawn through it, a topographical map of maybe the French provinces that appears to have been designed by an insomniac cartographer, and a luminous violet rectangle bordered by black and rimmed in blood.

Photo by Yxta Maya Murray. Alias Books East is one of L.A.’s used book jewels, like The Iliad Bookstore in North Hollywood and Oof Books on Cypress Avenue. At Alias there are books on witchcraft and poetry, philosophy, and fashion. They also have a serious collection of fiction: You can pick up treasures like a 1973 hardback of Graham Greene’s Collected Stories or a gorgeous Yale U. Press edition of Witold Gombrowicz’s Ferdydurke, with a bossy introduction by Susan Sontag.

Photo by Yxta Maya Murray. But Alias Books East also has a rotating art exhibit, which is the brainchild of owner Patrick Paeper and curator-artist Eric Johnson, who has been bringing shows to the shop since December of last year. Johnson’s selection of Fishbeck’s work proves inspired, since as soon as you walk into the tiny, lit-stuffed space, Fishbeck’s Alexander Calder-like face-wire sculptures and radiant canvases gallop up to you like ponies and make you panic with happiness. His show is called O, I Ask a Slob.

Photo by Yxta Maya Murray. My favorite paintings are Vanity Smog, a smeary ruckus of charcoal-grey and pink, and Stretches, Yaws, and Is Awake, that piece of unbuilt blue sky. Like the rest of the works, they reveal Fishbeck’s finesse with a David Hockney palette and his ability to conjure the exquisite out of the messy and unmade. The paintings look like a beautiful side-effect of myopia, which appears to have been Fishbeck’s intent: In his neurotic, all-cap artist’s statement, he yells “IT IS NOT MEANINGLESS. . . . LISTEN TO THE INDISTINCTNESS. FUCK FOCUS. THERE’S SO MUCH TO SEE IN A SNOWSTORM, AN INFINITY IN A BLUR.”

Fishbeck is some supercool rocker who formed the band Holy Shit with Ariel Pink, and who murmurs songs like Marriage Monologue or I Wonder Why on his now-solo effort, the 2017 LP Solid Rain. He also graduated from Harvard in 1998, and has had exhibits around town, in San Francisco, and at Yale. Despite this lofty CV, Fishbeck belongs to the class of artists who are known as “permission givers”—a phrase that, when I looked it up on Google, seems to have been hijacked by the self-help crowd, but which nevertheless describes cultural producers like Calder, as well as Louise Bourgeois, Sid Vicious, Carrie Brownstein, and Jean Dubuffet. All of those artists have special gifts for realizing rough and witty visions that observers may also feel that they share, and could possibly also communicate.

Photo by Yxta Maya Murray. While I stared up at Fishbeck’s busted sky and the pink smog, a man with a cumulus of white hair came up to me, smiling. “It makes you inspired, doesn’t it?” he asked me. “Do you paint?” I responded, and he nodded, shyly. “What kinds of things do you make?” He didn’t answer, but gestured awkwardly at Fishbeck’s work. I clutched my little haul of books (Kafka’s The Great Wall of China, as well as the Gombrowicz and the Greene) and, like him, felt agitated that I was not at that very moment attacking a canvas myself.

“What is Fishbeck like?” I harangued Paeper, who hovered nearby as I began eyeballing the manic artist’s statement.

“Oh, well,” the laconic book impresario coughed, looking down at the stacks of tomes on his desk. “You just have to meet him.”

The white-haired maybe-painter, Paeper, and I then stood around silently, our mutual social weirdness seemingly illustrated by Fishbeck’s stammering paintings. I opened the first pages of the introduction to Ferdydurke. There, Sontag declares: “To irritate, Gombrowicz might have said, is to conquer. I think, therefore I contradict. . . . “

It was one of those L.A. used bookstore/gallery moments.

Photo by Yxta Maya Murray. O, I Ask a Slob is on for two more weeks. Alias Books East’s next show stars Sally Parks, a watercolorist.

Alias Books East is at 3163 Glendale Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90039.

-

Carmina Escobar’s Fiesta Perpetua!

In ancient days of strife and warfare, a death squad of bird-women used the strategies of sound and seduction to destroy their enemies. Homer gave the Sirens a starring role in book 12 of The Odyssey, where they attempt to divert Odysseus from his returning home to Ithaca and cleansing his castle of enemies. The Sirens approach Odysseus’s black ship as it sails the western sea, and tempt him with the promise of omniscience: “We know all things that come to pass upon the fruitful earth,” they claim. The only way that Odysseus can fight off their temptation is to tie himself to his ship’s mast so that he doesn’t jump into the deadly waters. And so he passes them by, surviving their threat but also remaining ignorant of all the marvelous things they would teach him.

The Sirens have updated their strategy since the 8th century B.C.E., apparently shifting from vocal homicide to the nonviolent protocols of feminism, Dada, and relational aesthetics. One of their human descendants, the performance artist Carmina Escobar, appeared in Echo Park last Saturday, and mesmerized a crowd of onlookers with a series of esoteric songs. Her strange and perfect messages, titled Fiesta Perpetua!, were accompanied by the 40-member Oaxacan youth brass band Maqueos Music, conducted by Yulissa Maqueos.

Escobar is a sound artist from Mexico, currently based in Los Angeles. In 2014, she executed Massagem Sonora, which involved standing outside of LA’s Korean Bell of Friendship and singing multi-octave scales into the bodies of strangers. Hers was a curiously intimate version of sound-bathing and water-witching: Escobar had to test out various parts of the initiate’s frame—a portion of the chest, an arm, the middle of the back—in order to find the place of resonance. Then she would cup her hands around her mouth and sing a wordless aria into the place where flesh met bone in harmony. That same year, she also appeared on Ear Meal, articulating answerless Gnostic chants while pressing her lips to the stuffed bodies of sparrows.

Fiesta Perpetua!, organized by REDCAT as part of its PST Live Art LA/LA festival (Jan 11–21), constituted a leap forward in terms of physical reach, if not audacity (for her work has been fearless from the start). Escobar was slated to appear at 1 p.m. on the lake, and deliver a “community ritual of manifestation” that followed “a mystical algorithmic schedule.” This expectation created a sort of halo of creativity around the park: Arriving at 1 o’clock sharp, I wandered about the lake looking for manifestations and mysticism—and they abounded: Here were shaved-ice sellers with their polychrome umbrellas, magical-looking joggers, signs made of occult graffiti, and two teenagers fishing in the lake for what they said were “rainbow trout.”

But then I heard a sharp, coyote-like howl, and I knew that the performance had begun.

I ran to the west side of the lake, aiming for a small crowd of Angelenos wearing geometric spectacles and an air of lujo, calma y voluptuosidad. Their allegiance to REDCAT’s programming was also made visible by their wearing of bizarre little buttons that had been supplied by LA/LA organizers: There will be a porcelain bullfight, read one. There will be cutout carpet creeping up the walls, said another.

To everybody’s delight, Escobar suddenly appeared on the lake on a small raft, which was outfitted with three wooden megaphones. She resembled a priestess in her yellow-and-white tabard, long purple skirt, turquoise earrings, pink pashmina, and glitter-gold boots. Half-vanishing inside of one of the bullhorns, she began singing a high-pitched series of notes. Her song bore a delirious, if wilder, resemblance to the enchantment wailed by the evil Siren seen on Charmed in 2002, and also recalled the great diva Leonie Rysanek’s Salome from the 1970s.

But whereas those two monsters had murder in mind, Escobar delivered love-struck revelations that were only barely comprehensible in her yawps and glissandos. Maqueos Music marched over to the opposite side of the lake, blazing their tenor horns and bass trombones. In a series of call-and-responses, the band would swing into parade music, prompting Escobar to hoot out like an owl and cry like a wolf, before melting into a soprano’s coloratura.

Escobar’s election to forego language in favor of unlettered voice allowed her to express some of the secrets that the Sirens offered to Odysseus so many centuries ago. What did she urge us onto? Create community might have been one lesson. Or, Remember that you are alive could have been another. These axioms, however, seem poor and paltry when spelled out, at least in comparison to the extremity of Escobar’s singing. The gulf between words and voice probably signals how difficult it is to impart the true wisdom buried in her music. Likewise, if Odysseus had to take a lesson from the Sirens, he probably wouldn’t have been able to explain their knowledge, which covered “all things that come to pass upon the fruitful earth.” There will be a porcelain bullfight, he might have said to friend at a local bar afterwards. Or maybe he’d mutter something about carpet creeping up the walls.

Fiesta Perpetua! extended similar profound graces, and left me hungry for more unknowing: Escobar’s work is important, beautiful, and untranslatable.

-

There’s Still Art: Astrid Hadad

On Thursday evening, when performance artist Astrid Hadad began telling a glitter-bombed, sombrero-wearing rubber chicken that everything would be okay, I remembered that there was still good in the world. The day’s news had been completely crappy, and I had ridden into the Mayan Theater on a toxic tide of gloom. I arrived to see Hadad’s show, I Am Made in Mexico, which kicks off REDCAT’S Live Art LA/LA series. Taking my place in line next to a gentle-eyed Cal State LA Critical Masculinities professor, I started grumbling that I couldn’t take three more years of this presidency.

“It’s okay,” the professor said. “There’s still art.”

“I don’t know,” I gibbered. “Art can’t save us. We haven’t hit the bottom. There’s a nuke at the bottom.”

“All right, all right,” they soothed.

We went inside. The Mayan was packed with Latinx folks wearing buzzcuts, cats-eye glasses, and pretty freakum dresses. An Anglo person with wild silver hair and harem pants declaimed about aesthetics to a crowd of black-clad philosophers. Genderqueer heartbreakers in pompadours and cap-toes flirted with the girlz in the freakums. The DTLA cocktail of dragon sleeve tats and 40’s-style wiggle skirts, muscle shirts and mascara, began to heal hurt nerves like the balm of Gilead.

Then Astrid Hadad exploded onto the stage, which was lit up with a pink pyramid and huge blue hearts.

Wearing a crown of two-foot pheasant feathers and a solid-gold onesie, Hadad wasted no time breaking out into a song-and-dance number about ancient Tenochtitlán, mother city of Mexico. Hadad is famous for her zanily liberationist cabaret shows, which are inspired by Bertolt Brecht and the Afro-Caribbean—themed Rumberas films of mid-20th c. Mexico. She channeled an ancient Mexica priestess as she sang about Mother Moon, whom our ancestors once gazed at before they were exterminated by the conquerors. Hadad then began to free associate about how, in the 16th century, the Spaniards were the “gringo imperialists of their time” who capitalized upon the exploitation and submission of other countries. “When the Spaniards saw the Aztecs committing human sacrifice and a little bit of cannibalism, they thought the Mexican people were savages,” she said, shimmying her shoulders. “But they weren’t—they were poets and sculptors and scientists and warriors.” She shrugged, trying to reconcile the complicated attributes of Latino forebears. “Also, you know, they recycled.”

Upon this observation came a rapid costume change: With the aid of burly assistants, Hadad slipped into a massive headdress made of masks and a huge pink dress with heads on its skirt. “My outfit is like the wall the Aztecs built with the skulls of sacrificed people!” she explained. This transition led into a routine about Montezuma’s irreversible blunder of submitting to Hernán Cortés c. 1519: “When the bearded men of prophecy arrived,” she sang, from the perspective of a cinquecento cacique, “the King said that they were gods. The white soldiers rode huge beasts, with fire in their hands, and their bodies covered in metal. And in that mistake we surrendered our history and remained enslaved for 300 years!” Hadad did a can-can kick and made a moue. “But there is no use in crying!”

The crowd yelled and cheered, agreeing. I looked around but couldn’t find the Critical Masculinities professor anywhere. Meanwhile, Hadad executed another swift wardrobe switcheroo into a wide-skirted silver wedding dress, as a huge disco ball dropped from the ceiling. She began singing a jingle that resembled the groovy soundtrack of The Pink Panther. “Refugees are dying!” she hollered. She opened up a hidden panel on her skirt and unfolded it as if it were a pop-up book, revealing a black-and-white mural of a graveyard, with skeletons littered upon the ground. “A lot of people suffer for the ambition of the few! Powerful people say, ‘Give me your silver and I’ll drink your blood!’” All the while Hadad pranced back and forth with her arms outstretched: “La la la la la la la!!!!”

People were boogying in the audience. Two women, close to the stage, gyrated with their hands held high and huge smiles on their faces. What is this? I wondered. A political rally? A party? A particularly fun anti-government conspiracy? As I, too, swiveled my hips, I suddenly remembered a 2011 UCLA study finding that political oppressed minorities suffering depression could heal themselves by “actively engaged in learning, talking, and praying about [discriminatory] legislation as well as protesting it.”

I resolved that “attending an Astrid Hadad concert” should be added to that Rx. It felt way better to exult as Hadad crooned her indictments for genocide than to impotently brood at home about pass-through tax deductions and de-escalation with North Korea. The crowd boiled with excitement as she changed into a blue and yellow gown with a red tree embroidered onto it. Resplendent, she brought out the glittery rubber chicken, and began to serenade it with the classic ditty known as Cucurrucucú Paloma:

Cucurrucucú, cucurrucucú, Hadad sang in a high, warbly voice.

Cucurrucucú, cucurrucucú,

Cucurrucucú, dove, don’t cry anymore

She looked at the audience, gave them a wink, and threw the wobble-headed chicken across the stage. And then she just kept dancing, because even though Hadad’s work is soaked through to the bone with tears, despair, and grief for the dispossessed, she knew what the Critical Masculinities professor had reminded me of—and what I had almost forgotten.

Courtesy REDCAT; All photos by Vanessa Crocini

For info on more upcoming performances: Live Art LA/LA series -

Basquiat Behavior

There’s a picture that photographer Virginia Liberatore took of painter Jean-Michel Basquiat and Madonna in 1983. The two stars, who were dating at the time, had arrived at a party in full regalia—fedoras, big watches, leather jackets. In the image, Madonna resembles a cat, making a claw out of one hand and eyeballing the camera like a pretty predator. But Basquiat looks anxious and slightly blank-faced, as if he had just been stunned by a blow. His affect might be explained by the fact that the same year, his close friend, the black graffiti artist Michael Stewart, had been killed while in police custody: The authorities listed the cause of Stewart’s death as a heart attack, but an independent pathologist said he succumbed to strangulation. Liberatore’s is a mesmerizing document, capturing Madonna’s glamorous obliviousness and Basquiat’s inability to stay on brand while enduring the grief and shock that flows from racial violence.

DJ Michael Stock These same dynamics—fake vs. real, professionally chic vs. awkwardly authentic, insistently social vs. helplessly alienated—churned through the Broad’s last summer Happening, which was dedicated to Basquiat’s art and life. Basquiat began with visual artist and musician Damon Locks’ ambitious sound piece interpreting such paintings as Air Power (1984), which depicts a hatchet, an old man, a windmill, and a helicopter: Locks sat at a table in the Plaza, washed in violet light, as he played a series of stinging guitar licks off of a synthesizer and repeated phrases such as “his mother tongue is power.” Locks’ words offered a necessary reminder on a day when failing to perform the expected words or gestures (by, say, taking a knee) could earn a black man curses from the highest office in the land. As such, Locks started off the night on a high mark that proved hard to beat.

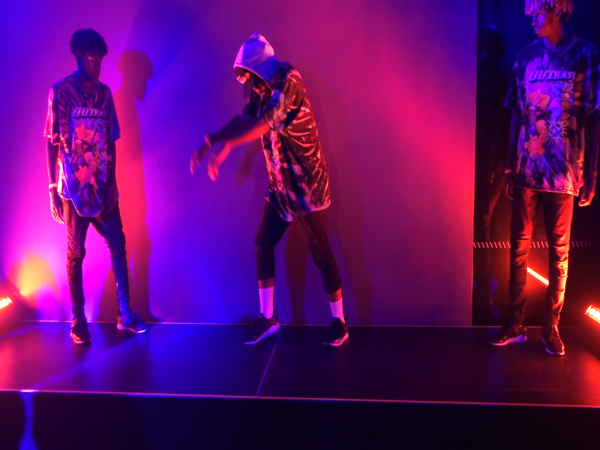

DJ Michael Stock His act almost was bested, though, by the dancers performing with DJ Michael Stock in the Oculus Hall. Stock, a punk specialist and DJ, played high-octane rhythms combined with ghostly vocals in the shadow-filled space. Bright purple and green lights flamed on James Thomas, Brandon Hunt, and Tavares Marshall, who mixed robot paces and literally deconstructionist popping to create a dance form that we here at Artillery had never seen before. Some of the performers were so double jointed that they could replace the ordinary ball-and-socket ergonomics of the human skeleton with something less banal: They sinuously cracked their bodies apart, reconfiguring their shoulders and hip joints so that they embodied creative contingency. Their performance reminded us of the human condition, illustrated by Basquiat’s shattering art, which requires us to destroy old, supposedly necessary models in order to fashion new approaches to the troublesome future. That the dancers enacted these themes while also swiveling gracefully to Stocks’ jams made them, for us, the #1 genius dancers that we have seen all year.

Zebra Katz Our joy at these two performances, however, proved slightly tempered when Zebra Katz took the stage on the Plaza. Katz, the stage name of performance artist Ojay Morgan, is a talented and “other” queer rapper who has forged identities and artforms with some of the same audacity as Basquiat himself. We were thus extremely excited as we began to make shapes to Katz’s innovative raps on the Broad’s lawn, until we realized that a great many of the words in Katz’s songs were actually just one word, and that word was “bitch.” Katz’s music often engages this epithet. Katz used it in their 2012 hit Ima Read, where they promise repeatedly to “take that bitch to college,” which does not seem to be a promise to provide financial aid, and in 2014’s 1 Bad Bitch, whose video shows Katz’s alter ego murdering four rich white women and then transforming them into taxidermy. Katz has acknowledged their indebtedness to this particular trope: “It’s seen as a very misogynist word in hip-hop but we’re trying to numb it,” Katz told The Guardian in 2013. As we danced to the anesthetized sexism, we here at Artillery tried to be cool like Madonna in 1983, when she didn’t make a political fuss and was just an adorable fun cat. To calm ourselves down, we attempted to read Katz’s deployment of “bitch” in the loving spirit of radical feminist Mary Daly, who in her Wickedary defined “bitch” as a moniker earned by “lusty” and “scary” women. We also understood that “bitch” can operate as a floating and multidimensional signifier. But, then, we realized, the taxidermy and murder stuff might suggest other, more conventional meanings. We continued gamely Macarena-ing through these doubts, but eventually we began to feel like a patsy and a hypocrite. We also wondered whether “numbing” was the wisest art practice, and had a bad flashback to Basquiat’s face in the Liberatore photograph. Then we wished we were back with Damon Locks so that he could make us interrogate power in ways that didn’t seem to suggest our own personal debasement.

Shani Crowe The anxiety we experienced during Shani Crowe’s performance in the Lobby proved of an entirely different quality, informed more by knowledge of the California Penal Code than of radical Wymynism or the painful revelations of structural and political intersectionality. Crowe is an interdisciplinary artist from Chicago, and she experiments with cultural coiffure and beauty ritual in order to narrate the diaspora and also foster connectivity. In the lobby, she kneeled on the floor and began to arrange strands of red, green and black fibers around her body. To her left stood a tall structure around which had been arranged a cape of painted paper. Crowe tied back her hair into a tight ponytail and then began to laboriously braid a heavy 15-foot extension onto her head, using the colorful fibers. She next stood up, walked over to the paper-enclosed structure, and ripped off its covering. In so doing, she revealed a man crouching at the bottom of a kind of scaffold. The man wore no clothing but BVDs and appeared to be Anglo. Crowe then yanked the man to a standing position, lashed him to the scaffold, and proceeded to energetically flagellate him with her long braid. She hit him repeatedly and hard enough so that red stripes began to puff on the skin of his shoulders and spine.

Mecca VA and the Movement We were able to read complicated meanings in this thrashing, which included not only an ode to the hopeful pleasures of BDSM and a critique of racist beauty standards, but also maybe Crowe’s retaliation for slavery and its atrocities. We stood in the crowd and looked mostly at Crowe’s colleague, who shuddered at every clout and bore an agonized look upon his face. We were very sure that he must have autonomously chosen to have occupied this contested position. Many people like to be whipped and this was art and he could call out for help at any time, we reassured ourselves. We attempted not to worry about the amorphous and often illusory nature of free election, which so often rests in the messy bed of imperfect agency, that human paradox of experiencing one’s liberty and one’s oppression at the same time. We were confident he must have a safety word. His back looked sort of injured. He probably also signed a non-binding waiver and had consulted with his psychiatrist and his lawyer before getting his ass beat in front of a bunch of strangers. That these strangers also had begun whooping and laughing at his abuse should not have deterred him from choosing to put a stop to the performance if he so desired, right? What was the crowd guffawing about, anyway? Now staring up at the jeering throng with which we mingled, we feared that our admittedly sporadic adherence to ahimsa might be interfering with our role as an art critic. And then, we also remembered that CPC sections 31 and 242 prohibit the aiding and abetting, that is, the encouragement, of non-consensual battery.

Jay Carlon Standing by silently was not encouragement but it also seemed bad. So we slowly stepped back from our front-row position, disappeared into the crowd, and continued to overthink everything on our way to the third floor to see the Jay Carlon dancers, who twisted and floated among the Broad’s Kara Walkers and the Basquiats like troubled gods. One woman with cropped hair and mustard trousers curled up on the floor, and then stood up and spun around until she felt dizzy and sick. She staggered around the gallery as if she might throw up.

We drifted outside to see The Downtown Boys play on the Plaza stage. The female singer wore a floral crown and bashed around, yelling “this is for everyone who ever did something they thought was impossible and wasn’t blunted by capitalism!” before breaking out into rock songs from their 2015 opus Full Communism.

We nodded our head along to the tunes, but felt the whiplash of participatory exegesis. Getting insulted, flirting with felony liability, and watching people dismantle themselves and barf is not, for us, a typical Saturday night. Was it all concocted and fake, like Madonna? Or were the performers and the crowd overwhelmed, like Basquiat?

We didn’t know. As we walked around the Broad’s fairy-lit campus, the evening air blew cool, and filled with chatter about police murders of people of color, black art, white money, nuclear war, feminist linguistics and celebrities.

And on these notes of engrossed bewilderment and psychic electrocution, came a close of the Broad Summer Happenings for yet another year.

Photos by Chris Jarvis

-

2017 Third Broad Happening

Artists and curators Ron Athey and James Spooner know that Los Angeles has become the art world omphalos and so decided to convert last Saturday’s Broad Happening into a 21st century Oracle of Delphi. Hosted in alignment with the Broad’s current multimedia show Oracle, which prognosticates on global anxiety and surveillance, the Happening featured artists who prophesied whether the earth will survive its current travails or careen off the cliffs of war and warming.

Ron Athey