So I’m at brunch at Figaro (on Vermont) with two of my best (and one of my oldest) friends from out-of-town; and we’re actually sitting outside on the hottest day of the year (I’m imagining the wait-staff making bets on my imminent demise). There’s a very tea-in-the-Sahara vibe – but then we could probably say that about almost any place on earth. (There was a piece in the Sunday Review section of that Sunday’s Times about ‘selfies and suicides’ in India which more or less seemed to sum up the direction we’re all headed in.)

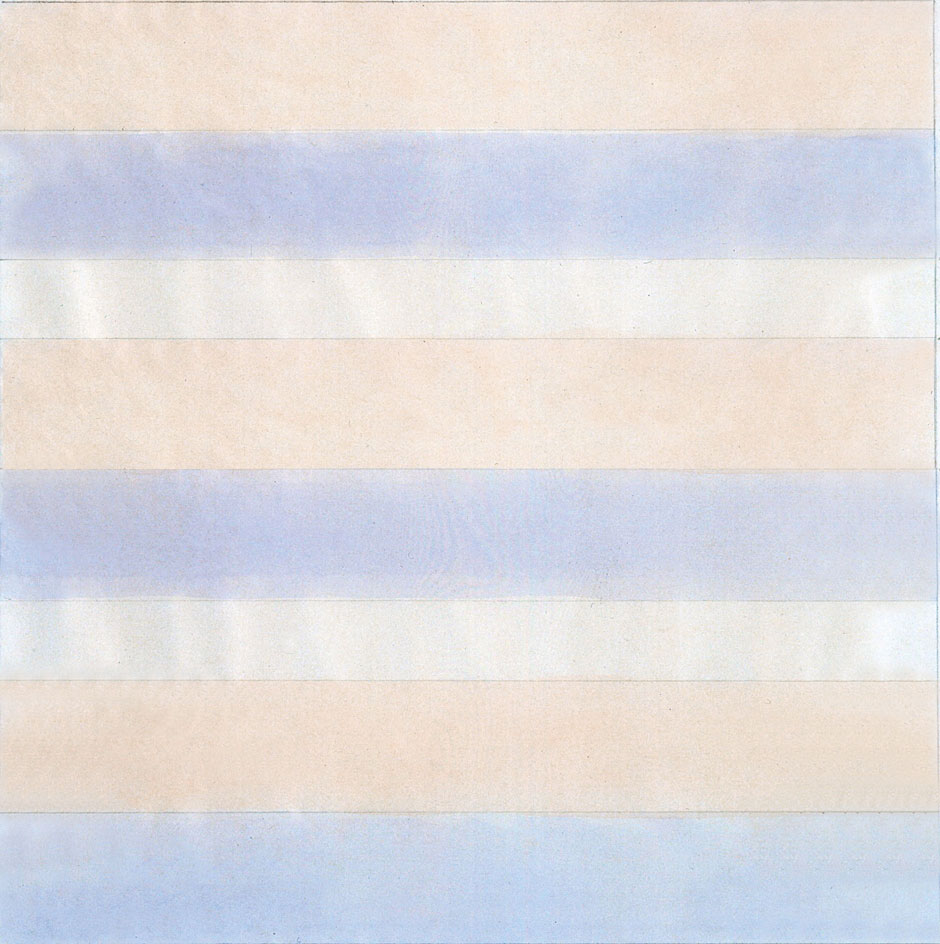

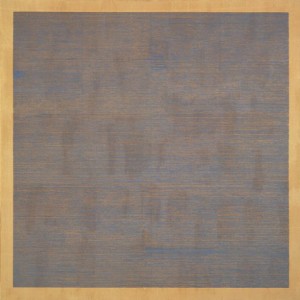

Agnes Martin, Friendship, 1963

So after the usual New York Times mastered misery, the news of the deal out of a Holly-World that has almost nothing to do with the Hollywood we grew up with, and the obsessions of the moment, we get down to the afternoon’s agenda which, in addition to the usual biblio and audio excursions (and a quick pass through the COLA show), is contested between the Cindy Sherman show at The Broad and Agnes Martin at LACMA. Martin’s name alone clinches it with one of my pals, but just for shits and giggles the other will entertain an argument for Sherman. Obviously Hollywood is a reference point here and the matter has been on my mind lately (see my last AWOL post – and maybe the next one) but I have a long way to go before this goes to court. No matter – on a day like this, it’s like a contest between going to the beach and going to the desert. (And why deal with the sand, sunscreen and crowds?)

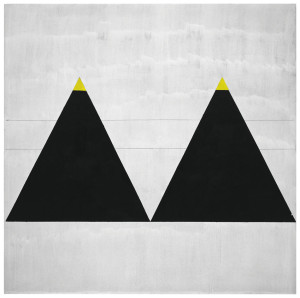

Agnes Martin, Happy Holiday, 1999, acrylic & graphite on canvas, 60 x 60 in.

LACMA is pretty crowded on a Sunday afternoon, too. But the third floor BCAM galleries given over to the Martin show are a meditative space by comparison. Your body temperature may drop measurably before you’re even through the first gallery. ‘Tea-in-the-Sahara’ – or perhaps it’s the Sonora in this instance – has been lifted to a contemplative mesa removed from the dunes and dust of the desert floor.

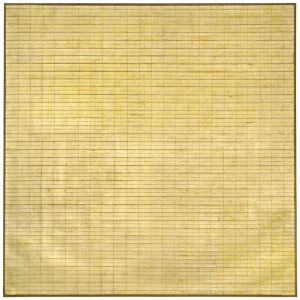

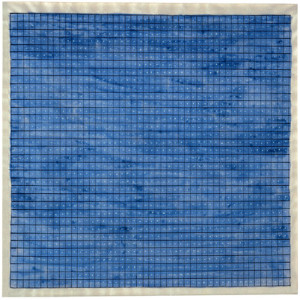

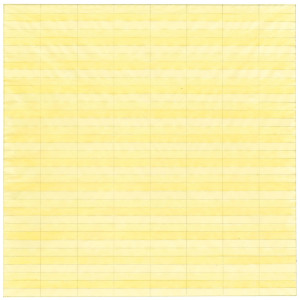

Agnes Martin, Summer, 1964, watercolor, ink & gouache on paper, 9.25 x 9.25 in.

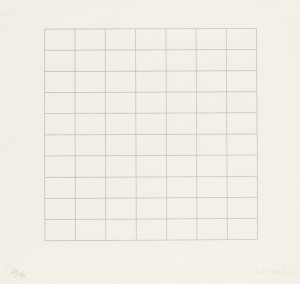

Agnes Martin is not infrequently associated with this distanced and not incidentally dessicated desert view – both in terms of palette and detachment. (There’s a famous photograph of her by Gianfranco Gorgoni taking in such a view from her home in Cuba, New Mexico – more or less equidistant from Taos, where she first settled after leaving New York, and Santa Fe – included in the show.) She doesn’t take the heroic stance of an artist like (obvious contrast) Georgia O’Keefe, nor does she ‘connect’ with the physical environment with the same kind of visceral abstraction – though the scale of her work gives some sense of its relation to both body and physical siting. I once took for granted Martin’s ‘placement’ (if you will) as a ‘desert’ artist, as insistently flat and abstract, a vision wedded to the insular perspex of the grid, and, de facto, a Minimalist. And although I didn’t even realize it at the time, I was pretty much through with the grid. I mean I accepted, treasured it as part of modernism’s legacy; had devoured Rosalind Krauss’s essay on the subject sometime in the early 1980s; etc., etc. – but really, as Leiber and Stoller would put it, is that all there is?

Bear in mind that at the time I’d ‘made up my mind’ on the subject, I’d seen maybe a half-dozen Martins in the canvas-and-pigment. In other words, I didn’t have a clue. I knew she had spent a significant period of time in New York, but I didn’t have any real sense of her history there until only a decade or so ago. Yes, you could call Martin a Minimalist – and many other things. But her style and sensibility emerge out of a much more complex and nuanced dialogue with her modernist (and for that matter abstract expressionist) predecessors and contemporaries (e.g., Robert Motherwell and Barnett Newman, as well as Frank Stella and Ad Reinhardt). She finds her way to the grid in due course, but her approach is both tentative and deliberated. You can practically read something of that dialogue and dialectic in her early works, conversations that were probably both interior and actual – with Motherwell, Arshile Gorky, Newman, and others. The work moves from represented undulating forms to the subtle undulations of pigment and color. The grid is simply the device that takes her ‘beyond geometry’ (if I might borrow loosely from that LACMA exhibition title) to something like a prismatic distillation of an essential reality. This was always, on some level, a metaphysical investigation.

Falling Blue, 1963, oil & graphite on canvas, 72 x 72 in.

There is an undeniable Minimalist aspect to this, but Martin’s work moves in a very different direction from those gasbags that thought painting (a ‘rectangular plane placed flat against a wall’) just wasn’t ‘specific’ (or maybe ‘primary’) enough. Seriously. I once thought Minimalism read better than it actually looked. In my limited retrospect (it wasn’t as if I was going out of my way to look for it), it seemed more of a sophomoric philosophical exercise spurred on by an overheated reading of Wittgenstein’s Blue and Brown Notebooks, then a response to the art (possibly with the exception of Claes Oldenburg) immediately preceding it. Somewhere in the back of my mind I wondered whether they were simply caught between envy for the manifest genius of, say, Jasper Johns, and frustrated at the exhaustion of Pop. What could possibly be left to do?

The answer (predictably) came from contemporary music and dance, and a bit more amorphously from European sources (including literary and, yes, philosophical – e.g., Wittgenstein and his English logical positivist heirs). Taking their cue from some of these influences, a number of proto-Minimalist works began as performances or performances with or amongst objects. (Oldenburg epitomizes this of course; but there were others – e.g., Robert Morris.) John Cage’s own lectures might be considered prototypes for this type of performance; and certainly his work with Merce Cunningham (and not incidentally, Robert Rauschenberg) anticipate this direction. His lectures, published as Silence in 1961, in which he borrowed freely from such disparate sources as Zen philosophy, contemporary music and dance, and Erik Satie, limned the parameters of what would emerge in Pop’s explosive wake and well into the 1970s as abstract ideas gave way to pure conceptualism.

I remember revising my opinion around the time of a cluster of museum exhibitions focused on Minimalism and its impure, secondary heirs. MoCA’s show was particularly memorable – and not just for its Agnes Martin(s) (a pair, as I recall, at least six feet across). Bracketed chronologically between 1958 and 1968, it gave some notion of Minimalism’s complex, fractured, and far from aesthetically seamless touchstones. (LACMA also had a show, Beyond Geometry, not far off from MoCA’s exhibition run, that encompassed a good deal of Minimalist art.) Walking around that expansive show that (handsomely) took up the entire Grand Avenue site, I decided that Minimalism was really all about real estate.

And maybe it is. But the weird thing is that there is some foreshadowing of that ‘Minimal future’ (the title of MOCA’s exhibition) that we’re only grasping now – the future that calls into question our relations with physical space, with objects (and each other), the nature of who and what we are and the way we apprehend it. It is a daunting realization that language is not entirely sufficient to grapple with; a space that – hearkening back to that moment of Cage, Cunningham, and, well, Agnes Martin – we measure in silence. It could also in a sense be a reflection of the distance – physical, mental, temporal – we have to travel between those actual and virtual points.

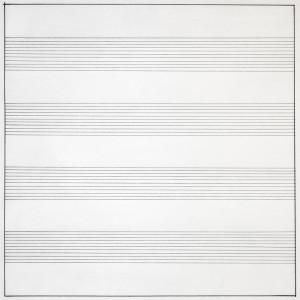

Martin knew something of those distances, both physical and psychological. A schizophrenic break triggered her temporary abandonment of painting and permanent abandonment of New York, ultimately making her way back to New Mexico, where she finally emerged from her hiatus from art with a sequence of screenprints that are in effect a kind of personal manifesto, or prolegomena for an approach to distilling and synthesizing her perceptions into the stuff of her art. It is the groundwork for a project of personal transcendence. She called it (implicitly distilling that desert mesa view under full sunlight), On A Clear Day.

The installation, which takes up the entire BCAM third floor uses On A Clear Day as the transition between the two halves of the exhibition, the first half taking us through 1967; and the second half picking up after On A Clear Day, in 1973. I haven’t seen the catalogue, but the curation and installation – by Michael Govan himself – is, quite simply, flawless. In addition to feeling your body temperature drop as you move through the galleries, you may feel your breathing change. It’s as if the installation had somehow internalized Martin’s Zen spirit. It’s Martin, in full – the macro and micro-view – taking us through each permutation, each modulation, each celebration of the moment-by-moment respiration of an experience and atmosphere as Martin transmutes them to paper and canvas. (It may seem like sheerest chutzpah to title a canvas broken down to six gray bars, Fiesta; but Martin is making a statement of pure transcendence here.) Throughout, there is a subtle balance between colour modulation (or a kind of colour ellipsis) and the visual rhythm and punctuation of verticals and horizontals discretely registered yet apprehended as an enveloping whole. It’s breathtaking the way a 6×6 foot canvas can convey the subtlety, the intimacy of a mood or impression no less than a 9×9 inch gouache; and conversely that the small gouache or watercolour can convey a sense of the scope and magnitude we take from a larger work.

Gratitude, 2001, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 in.

We can call Agnes Martin a Minimalist; but to leave it at that is to miss more than half the story, and the critical half at that. Her work forthrightly proclaims both its austere limits and boundaries and the vulnerability of its flaws and limitations. Martin’s art is fundamentally one of idealism and transcendentalism.