Editor’s Note: In lieu of our usual reviews and gallery rounds, we will be running a special SHELTER-IN-PLACE series for the duration of social distancing. This series will focus on that which can be enjoyed from home: musings on stream-able films, online art, and memoiristic reflections on colors, permanent collections, and craft. Thanks for sheltering with Artillery, and we hope to see you at our usual gallery rounds soon.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Modern Times: American Art 1910–1950 (April – August 2018)

Long ago when I was reading Vita Mia*, the autobiography of Pietro Consagra, the Italian sculptor whose work was such an important part of my art upbringing, I was particularly fascinated by the part in which he stated that one must always be prepared to be swept away by something unexpected in terms of aesthetics and beauty. At the time, I swore to keep the portals of my perception open and never cease to be vigilant about how habits and the disinclination to look at things, would cause me to not notice something important.

Turning into the rooms where the 2018 American Modernism exhibition was, I felt pretty firmly ensconced in the idea that I was going to get to see a lot of things that I already knew about so I wasn’t particularly excited. It was sort of like going into a party where you already know everybody. The first inkling that something was amiss about that feeling was seeing the large number of artworks that would not have on my list.

Almost immediately upon entry stands an astoundingly vivacious aerial view of a shopping spree. Flanked on each side of the canvas by deep red swathes depicting curtains and a stairway are scenes of women sorting through, trying on, and dancing around a series of gabled partitions and lounges. Florine Stettheimer’s Spring Sale at Bendel’s, 1921, brandishes brightly explosive colors and the sheer intensity of the choreography is abundantly celebratory. Next to it on the same raised platform is a manikin sporting a red dress from the same era. Together they conjure up the energetic convergence of early modernism.

Installation view of the 2018 exhibition, Modern Times: American Art 1910-1950, courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art

In a wonderfully incongruent group of portraits, Alice Neel’s portrait of John with Hat, 1935, Beaufort Delaney’s Portrait of James Baldwin, 1945, the Chester County Art Critic (Portrait of Christian Brinton), 1940, by Horace Pippen and Dorothea Tanning’s decidedly metaphorical self portrait, Birthday, 1942, that all share space next to one another. Rather than create common denominators, the array gleefully exults in entirely different applications of color and stylistic continuums. Far from being an art historical exercise in chronology or a lesson in stylistic evolution, they evince the wide bandwidth of art experiments being carried out in that time.

Elsewhere there are examples of work by artists who are generally known for other canonical works. Marsden Hartley’s almost diagrammatic Sextant, 1917, is flanked by Arthur Dove’s near cruciform, Gear, 1922, while a little bit further over Morton Livingston Schamberg’s Painting VIII (Mechanical Abstraction), 1916 performs its machine-like liturgy. All of them not what you just expect and yet all completed with the shared intention of putting objects into entirely unexpected orbits.

If the intention of this exhibition was to revisit an era through the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s encyclopedic collection and, in light of what we think today about that time, reshuffle the deck of what things to look at and how to add them up differently, then it was spectacularly successful. If the result was to facilitate a pleasure-filled and unexpected dive into a time when so many artists were staking out modernism as a pluralistic, synergetic, and unstable time, then it prompted me to go back to Consagra’s urging and allow myself to be swept away.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Marcel Duchamp

Sometimes when you live with the thought of something long enough in your life, you feel like you’ve already known all about it and somehow it’s something that you have a perceptual hold on. Most of my formal art history and art education took place in Italy so many of the canonical figures and even historical movements are different from LA but one aspect that was central was the art of Marcel Duchamp. In part this was because he was an artist who traveled between Europe and the United States, in part, it was because he is such a polarizing figure. His work had been at the center of so many discussions at the Accademia, it felt like I knew everything about Duchamp that anyone would ever need to know. It wasn’t until I was walking into the museum where my friend Jessica Todd Smith who had recently relocated there from the Huntington that I realized I was going to see some of his art which never travels.

The first thing that happens when one crosses the threshold of the Duchamp room is the art there is no longer an image. The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-1923 is really big. It kind of towers over the viewer and is placed in a room in which there is an outside window on the closer side of the rectangular room right in front of the artwork, so it is bathed in reflections that have a lot of movement in them. The small steel railing that surrounds it keeps anyone from getting very close to it, so actually it is easier to study it more closely in reproduction in person. Yet it was strangely thrilling to see this artwork, and I say strangely because I have always thought Duchamp’s renown as the artist to turned all art towards the conceptual meant that the work would not be visually interesting. It was absolutely captivating: finally, it materialized as something, standing in incidental lighting, with all its crystalline details right there.

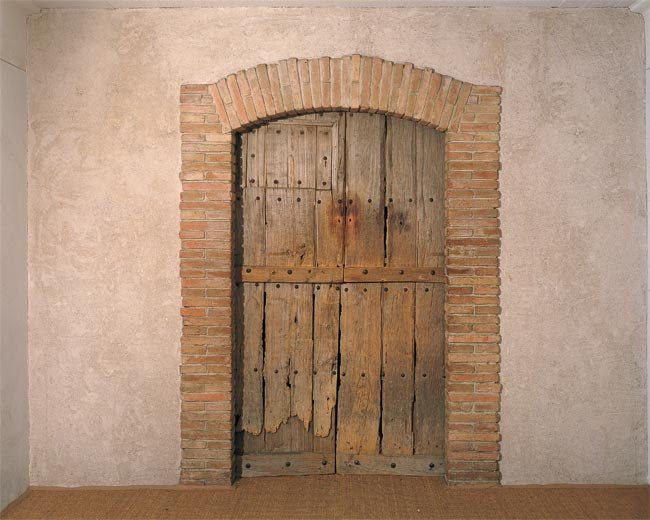

“Étant donnés” 1946-1966, by Marcel Duchamp. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp. Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of the Cassandra Foundation, 1969.

In the slightly darkened adjacent room is the wall into which the wooden door in which the peephole that gives onto Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau, 2° le gaz d’éclairage . . . (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas . . . ), 1946-1966 is embedded. This work also was something that I thought I knew, but the odd position that the viewer must put themselves into in order to look into the work is just the start of its disconcerting qualities. There is a question of measuring how long it is reasonable to occupy the peephole. After leaning into the viewfinder, the eye has to circle around in order to focus on the various parts of this work in its staged camera box. Aside from the many optical illusions that were a part of this artist’s life work, it is hard not to find a sense of queasiness growing as it becomes clear that this is not just the conceptual event but it is actually a visual banquet. Add to that the complications of sexuality, the presence of the notion of some gaseous thing as a kind of energizing flux common to both this and The Large Glass next door and it becomes a very tantalizing rebus. What were the points of the stripping of the bride or the laying out of this woman/landscape? Was there one rationale or were there multiple pulsations that the artist acted upon? In the midst of mulling these ideas over, there is this incredible display of palpable art-making ability in both works. It wasn’t just engagement for the mind but the senses of the haptic and the optical that are activated and energized by these works. Coming away from the rooms in which Duchamp’s explorations were collected, the most palpable sensation is that for however fascinating the talk and stories that circulate around his work are, the artworks themselves go far beyond that. They have that presence of an art form that is extraordinarily thoughtful as well as ineffably visual. I guess you’d have to be there.

0 Comments