I always thought that Phyllis Diller’s public/comic persona (the hair, the toothy smile, the A-line dresses and feathery accessories, gloves, booties, cigarette and holder) was her greatest work of art. But she was also a pretty great comic and (with a little help from a couple of male comedians) broke some pioneering ground for the women who followed her into the business. Less obvious, and something that only emerged gradually over the course of her career, was the fact that she could have made a success in almost any field. She was a complete brainiac. But her pathway was not always clear. A classically trained pianist, at one point she might have pursued a career as a concert pianist or gifted recitalist and teacher. But life had already dropped its pile of lemons on her and she made it the stuff of her comedy. Three decades later, wealthy and wildly famous, she was approached by a Midwestern symphony orchestra for a fundraiser; and after making a joke about it, pitched the idea of actually playing with the orchestra. She was successful enough to make a tour of such dates. Concertizing in the classical music world is arduous though, as second careers go; and comedy would always be more lucrative.

She had long dabbled in drawing and painting and (always ahead of the curve) had donated one of her earliest paintings to a show of “celebrity art” in the early 1960s, but had never seriously pursued it. Not long before her charity concertizing (the mid-1980s), she had begun to paint and draw again, largely as a hobby; but as the gifts, tokens and requests from fans and friends mounted, she began producing them in some quantity. She was serious enough to consider formal training, but dropped it after only a few classes. There was nothing she needed to learn; and—as John Baldessari might put it—who can teach anyone to be an artist anyway?

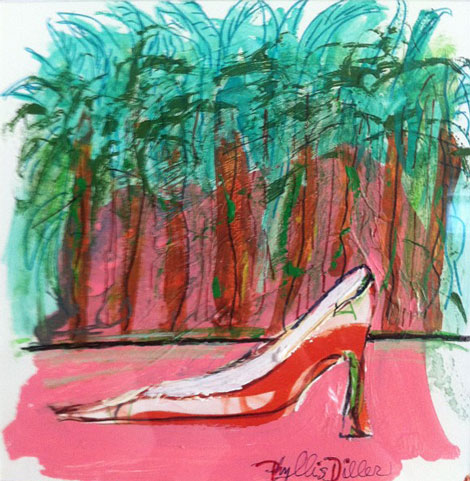

Her style runs the gamut from the kind of accomplished amateur styles in vogue among her Hollywood peers (think Anthony Quinn, et al.), approximations of contemporary commercial styles (think Leroy Neiman and his ilk; and the various graphic illustration styles seen everywhere from advertising to TV Guide), to a kind of pastiche School of Paris style (Matisse, Raoul Dufy, Marie Laurencin) filtered through Jay Ward in his best Fractured Fairy Tales form.

It’s really a 1950s graphic/decorative aesthetic updated with 1960s Pop and psychedelic (e.g., Peter Max) palette. But as ridiculous (and hilarious—her gift for comic delivery was inescapable) as some of them look, there’s something undeniably smart, strong and pure about her line. She understands how the line expresses and embodies the style, contains and carries the image. She understands its power and uses it deftly—sometimes reducing it to something almost resembling an ideogram, sometimes just throwing it away. Some of her paintings come across as almost surreal jokes. (Even pursuing a hobby she was in a hurry and looking for a fast laugh.) Had she been serious, she might have had some success as a commercial or editorial illustrator. But I’m guessing she would have resented her editors for stepping on her laughs. She needn’t have worried. Predictably, she seems to have had the last laugh: her remaining paintings are still selling.