Narrative art has been displaced in recent decades, not simply from the modern art canon but from serious consideration in the contemporary fine art context, generally—which is somewhat ironic, since it dominates the Western art historical canon through the 16th century and remains a mainstay through at least the following two centuries, and moreover, continues to be referenced in 20th and 21st century art.

Narrative art has been displaced in recent decades, not simply from the modern art canon but from serious consideration in the contemporary fine art context, generally—which is somewhat ironic, since it dominates the Western art historical canon through the 16th century and remains a mainstay through at least the following two centuries, and moreover, continues to be referenced in 20th and 21st century art.

To the extent narrative has crept back into art in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, it is quickly denigrated as ‘illustration,’ or relegated to the status of ‘outsider’ art. Which is not necessarily a bad place to be if you’re trying to create original work in this media-saturated culture. As conceptualism gradually recedes from its dominance in the contemporary art world (the longest fade-out in art history); as audiences probe for a sense of visceral connection to contemporary experience or actualities beyond the quasi-academic or ad-hoc theorizing (or posturing) underlying so much contemporary art practice, or the debased rehash of mass culture memes that are a drug on the art market, the ‘outside,’ marginal, extreme, or what was once the domain of craft, folk art, the bricoleur or street artist, seem increasingly viable points of departure.

To the extent narrative has crept back into art in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, it is quickly denigrated as ‘illustration,’ or relegated to the status of ‘outsider’ art. Which is not necessarily a bad place to be if you’re trying to create original work in this media-saturated culture. As conceptualism gradually recedes from its dominance in the contemporary art world (the longest fade-out in art history); as audiences probe for a sense of visceral connection to contemporary experience or actualities beyond the quasi-academic or ad-hoc theorizing (or posturing) underlying so much contemporary art practice, or the debased rehash of mass culture memes that are a drug on the art market, the ‘outside,’ marginal, extreme, or what was once the domain of craft, folk art, the bricoleur or street artist, seem increasingly viable points of departure.

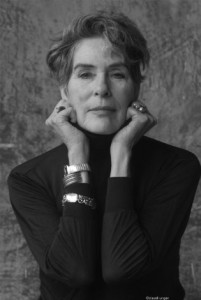

Mary Woronov has always stood outside: as an artist (even in a sense from her own technique and craft), as an actress, and as a writer. You can see it from the earliest moments of her career: the distance she seems to impose from the lens of Warhol’s camera, a self-possession that gradually gives way to selective disclosure that in turn elides to a subtle optical tug-of-war—‘I’ve been watching you, watching me….’—before settling back comfortably into an entente not quite cordiale. Whether as Hanoi Hannah in Chelsea Girls, or her roles in the smaller Warhol/Morrissey films, she holds the screen with an understated yet all but impregnable authority. By all accounts, she displayed a similar authority on stage.

Mary Woronov has always stood outside: as an artist (even in a sense from her own technique and craft), as an actress, and as a writer. You can see it from the earliest moments of her career: the distance she seems to impose from the lens of Warhol’s camera, a self-possession that gradually gives way to selective disclosure that in turn elides to a subtle optical tug-of-war—‘I’ve been watching you, watching me….’—before settling back comfortably into an entente not quite cordiale. Whether as Hanoi Hannah in Chelsea Girls, or her roles in the smaller Warhol/Morrissey films, she holds the screen with an understated yet all but impregnable authority. By all accounts, she displayed a similar authority on stage.

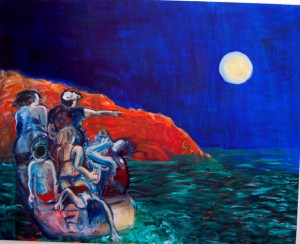

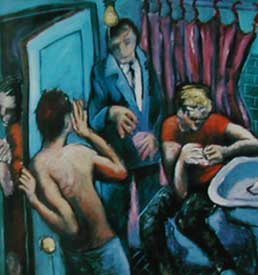

Yet her style has always been her own, sui generis, a thing apart. High inside with the in-crowd, you have the sense of someone with one eye on the exit. Ready to get up, open the door and walk out—she has never been one to stay too long at the fair. She has spent a good part of her later career opening such doors; but more often than not, these doors open onto spaces of her imagination. Woronov has a terrifically expansive physical sense (one to match her imposing physical presence—there’s a reason her first serious formal artistic pursuit was sculpture), and it informs all of her work. But the scenes she composes, whether interior or exterior, landscape or storyscape, are cropped or stretched to proportions dictated by narratives seemingly assembled out of both dream and actuality.

Interior or exterior—they all become storyscapes: genre scenes that unravel into sly bits of comedy or (more often) drama; social, sexual, or familial dynamics that threaten to explode into conflagrations, or tensions languidly melting away; less-than-innocent pastorales that devolve into swampy denouements or bloody carnage. Even her ‘landscapes’ seem charged and febrile, taken from a place that exists nowhere on earth. Every scene (and they are scenes) has a ‘primal’ quality. She is looking for a fundamental drama or conflict at the heart of the pictorial dynamic.

But the work also drives towards something deeper, more essential: the lost mythic stones and germs that built this madness we call civilization; fundamental truths of human character—the absurd, solitary madness of just being. The viewer sees this in some of her smaller works—the figures in pose or repose, solitary, almost silhouettes—genre studies that have the power of icons; plants borne out of some botanical nursery or garden in hell; the smaller landscapes. Woronov understands the iconic down to the bone.

The Woronov icon is something of a work in progress—and I sometimes wonder if the film documentar(ies) of her enigmatic life and work, seemingly continuously edited and re-edited, are fated to being ‘definitively unfinished,’ like Duchamp’s Large Glass. A tempting foretaste of one such documentary may be sampled currently at the Laemmle NoHo 7, Mary Woronov: Something About Mary (part of their Art in the arthouse series), along with a gallery exhibition of her work (both large and small, older and more recent work). A brief clip of Woronov, draped in a long coat or duster and walking, dancing on a beach, near the beginning of one trailer, has the quality of a Lartigue photograph. ‘Let me tell you a story,’ the trailer beckons. As in the paintings, we are headed to a similarly timeless place, flickering both light and dark, before finally dissolving before our eyes.