From the shaded parking lot, a stark beam of light shines through the loosely shut double doors of a nondescript white brick building. It is late morning, and the sun is already beginning to assert its presence as I approach the now-defunct Regen Projects gallery. It looks eerily empty; I wonder if I have the wrong time for our meeting.

I knock softly on the door and loudly whisper, “Lari?” Los Angeles painter Lari Pittman immediately responds and throws open the doors to expose all the sunlight-filled atrium—an oddity for a gallery, I’ve always thought.

I am meeting Pittman to view the new work for his upcoming November show with Regen Projects, which will be exhibited at their palatial new space on Santa Monica Boulevard a few miles east. Pittman is using the former West Hollywood gallery as his temporary studio—where he is able to keep three 30-foot paintings hanging on the walls, along with a raft of paintings on paper—so he can work on everything at the same time: a customary studio practice of his. Indeed, three very large canvases take up three very large walls. As I stand in awe of the formidable, unfinished paintings, Pittman announces that they are flying carpets.

Lari Pittman, Unfinished version of, “Flying Carpet With Magic Mirrors for a Distorted Nation,” 2013, photo by Rainer Hosch.

Right away he shows me his one and only “plan” for the flying carpets—a torn piece of brown paper, not unlike the texture of a grocery bag, with some scribbles on it. He explains, “This is the original drawing for these. I don’t really do prep drawings.” He delivers this fact with such seriousness that it almost feels like a joke, but he’s not laughing.

The plan consists of three scraggly lines, each pointing to a caption. “These titles were established right from the beginning, before the painting started,” he claims, and points to the far right wall. “The painting over there is called Waning Moon over a Violent Nation.” He points to the second painting on the other side of the gallery, telling me the title is not fully resolved, but the third is, and he spins around to the far wall directly in front of us and blurts out, “A Flying Carpet for a Disturbed Nation.”

There is a brief silence as we stand before the flying carpets in all their enormity. The three paintings start with a black base and all have a repeated textile pattern, much like a tapestry rug. Huge hand mirrors grace one canvas (no reflections yet), another has two large telescopic lenses depicting airbrushed blurry distant landscapes, and the third one features what Pittman calls Petri dishes. All have a big thick, jagged white stripe of paint coming off the canvas. What remains empty or filled is yet to be determined. The hugeness of the paintings is daunting. It’s hard to believe Pittman never uses assistants. He employs a few to prepare his canvases, but that’s it. He paints every inch of canvas with his own hand—and he cleans his own brushes.

As we walk back to the makeshift table that has apparently been set up for our interview, I notice he looks remarkably bright and healthy, especially since he just returned the night before from a trip to Mexico, and, I learn, a recent surgery. He’s a young-looking 61-year-old with smooth olive skin and dark eyes that pierce through stylish black-rimmed glasses. He is dressed casually in a crisp blue-and-white checkered shirt and slacks—not, I imagine, what he wears while painting. We sit down to a spread fit for a cocktail party: two kinds of cheeses, fresh purple grapes, mixed nuts and sparkling water. He even has a Starbucks cappuccino waiting for me, and apologizes that it might now be lukewarm. It seems standard practice for Pittman to do this for any visitor. I felt I was in the company of a person whose mother raised him well.

Look Inside Now

The complete oeuvre of Lari Pittman, with over four decades of work, includes a playful combination of imagery ranging from typography to pornography, decoration to abstraction, confection to perversion, and light to dark. I was interested in the dark side of Pittman. His work seems so celebratory, happy and pleasing-to-the-eye. Yet in the mix of mirth, there are guns and nooses, blood and feces, tombstones and coffins.

I can’t help but think the violent nature of his paintings harks back to a cataclysmic incident in his life. It’s common knowledge to anyone who knows Pittman: In 1985 he suffered a near-fatal gunshot wound from a burglar who entered the Echo Park home he shared with his life partner, artist Roy Dowell. Aside from the psychological trauma one might experience from such an inexplicable intrusion, there’s also the physical aspect of a gunshot wound. Pittman recently had his fourth related surgery. He explains, “I’ve had to have my intestines completely reconstructed again. When you’re shot in the abdomen, the bullet goes straight through. But your intestines are all coiled, in a complicated way, so one bullet can make 50 perforations.” He adds, exasperated, “This insane gun debate in America. I think people who haven’t experienced this—and thank God—don’t realize that actually most people who are shot have chronic problems for the rest of their life. I mean, they are lucky to be alive.”

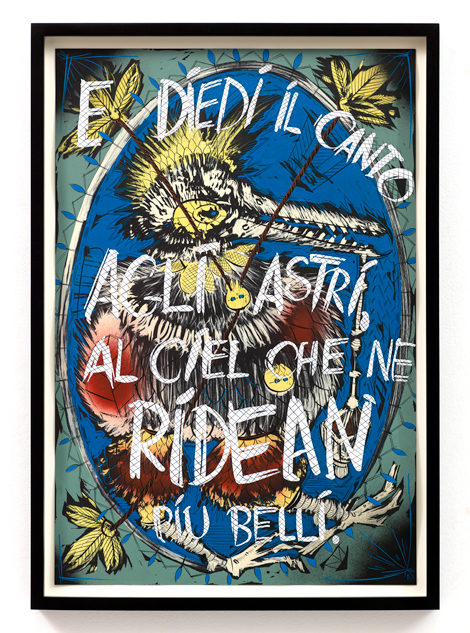

Lari Pittman, From “National Anthem and Lamentation Duet with Birds (After Puccini),” 2013, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Lari Pittman

It has been said Pittman’s paintings changed after that horrendous incident. Yet they are not autobiographical, he claims: “They’re personal, but not necessarily directly autobiographical,” he says. “If it’s really just exclusively expressionistic or autobiographical, I don’t see how you can enter work, and make it available to people. The viewer has to be able to have the capacity to superimpose their set of experiences over it too. I think that’s fair.”

I certainly didn’t want to argue with Pittman, but the flying carpets make me think about his tragedy. Whenever I see guns in his paintings, I can’t help but think they refer to his near-death experience. On a second viewing of the paintings, there are now images of bullet holes through the carpet, guns on another, and nooses again, all recurring motifs in his work.

Without being asked directly, Pittman did elaborate on the significance of the flying carpets. “I think it’s a strange combination to have what they’re depicting and then putting them on a carpet, much less a flying carpet. Perhaps it starts asking questions like who is going to get on this carpet?” he coyly suggests. “The reason they are so large is maybe either the entire population of a nation could get on the carpet ostensibly. Or some members could be self-selected and get on the carpet and some people banished. So it remains quite open. In other words I think the flying carpet is maybe an antidote to the disturbing nature of what is being depicted on the carpet.”

Pittman is not going to tell me exactly what the paintings might mean or represent, and maybe he’s not entirely sure at this early stage of the process. In his past work, socio-politically charged themes would often dominate a painting. I can tell he senses (correctly, I admit) I am looking for that again in these carpets. Pittman explains that his work has changed a bit. “If there’s a main shift in my work that’s detectable in the last many years it’s that it’s moved away from the moral, overtly socio-political to more the poetics and politics of philosophy, a philosophical rumination on life, self and culture. In other words, to keep work locked in a socio-cultural discussion—I can understand it. But I think it was wearing thin for me and I really wanted to pump it up. I still touch on politics, but more in a poetic way, in a more veiled way, and not so didactic.”

I ask him if that applies to all the sexual references in his paintings, i.e., colorful ejaculating penises, vibrant pink anuses, copulating couples. Some suggest that Pittman’s content can only be decoded by the gay population. He laughs at this supposition, “Let me just put it this way. I’m not straight, but yet I’m an expert on heterosexuality. Because I’ve studied it, I lived with it, I know everything about it, its quirks, its nuances… [Would] an interviewer ask a straight artist to contextualize their practice within their heterosexuality?”

This reporter stands guilty as charged. I can tell Pittman is not exactly thrilled with my question, but he also doesn’t want to change the subject. “On one hand I operate from complete social centrality and privilege,” he continues. “And on the other hand, I’m aware of differences. It’s amazing how it seems that men and women are really different from each other. I look at heterosexual relationships [with] their own protocols, their own proclivities, pathologies and so forth. But I guess I’ve made it my business to study human nature. All human nature. So when I’m asked about what constitutes my human nature, within the brackets of it being either a social subset or looking or behaving a certain way or smelling a certain way, or being perfumed in a certain way, it really is hard for me to answer. If anything, I recoil from answering. And part of it is that I refuse to defend myself in that way, or to provide that service of articulation for a hetero-normative world of what constitutes Lari’s homosexual aesthetic or point of view, if that is what they are asking.”

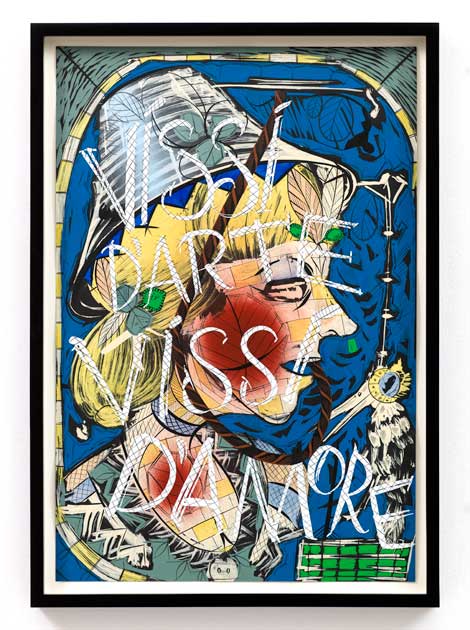

Lari Pittman, From “National Anthem and Lamentation Duet with Birds (After Puccini),” 2013, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Lari Pittman

Pittman appears a little defensive at the moment, maybe even a little agitated, and who can blame him? But he seems like a really nice guy. He backs down a bit, pauses and comes back with a softer demeanor, “I know that people ask that. I think the way the work looks comes out of a certain complexity of the person making it—me. I think I have a complex gender identity and will always have that. Those are very powerful lenses through which language and visual language is expressed. The identity that frees you can also be the identity that confines you. This anxiety about one’s gender is something I hear about a lot from my female friends. I don’t hear it that much from straight males, talking about their straight maleness, causing anxieties about being out in the world. I would say I’m talking about human issues. And part of it is your identity.”

Tell Your Dreams To Me

That nice-guy part of Pittman—that congeniality, that sensitivity, that polite concern—can only come from a proper upbringing. Where’s the prerequisite dysfunctional family? Pittman comes from an unusual background for an artist—complete normality!

He’ll be the first to admit he’s lived a relatively privileged life. He isn’t apologizing, just making sure I know that he is aware of this fact. “I was encouraged my entire life. In that way, as a human being, I’ve been very lucky,” he says. “That’s sometimes maybe why I react so strongly to the way the world behaves—or the art world behaves, because I really grew up in a cohesive world, and so did Roy. Both of our mothers’ professions was being stay-at-home moms.”

Pittman was born in LA, but spent his early childhood in his mother’s native country, Colombia, with his American father, one brother and an adopted sister. The family moved back to the Los Angeles area when he was 11 and Pittman attended Catholic school. He went to UCLA for a few years, then transferred and eventually earned his masters degree at CalArts. At that time, the school was a hotbed for the Pictures generation of the ’70s. Some of Pittman’s peers—Troy Brauntuch, David Salle and Eric Fischl—would become famous.

There was very little painting going on then at CalArts, where most of the work was appropriated or conceptual, but painting was Pittman’s passion and he made what was considered a risky decision to make that his focus. “People assumed that it would be ridiculed,” Pittman recalls. “But that was absolutely not true. I think people were excited that someone wanted to take on painting at a point where it was critically degraded or not on the radar as something exciting or sexy.”

Did he know he was going to make it as an artist? “Those expectations weren’t as concrete as they are now,” he answers. “But I can see them in my students now. For me, it was really clear: This is what I want to do. I remain as ambitious and driven to make work that means something. That’s the one thing that hasn’t changed in me and that I had as a really young person. I didn’t project, in terms of making a living, per se. And don’t forget, LA in the ’70s was much cheaper to live in.”

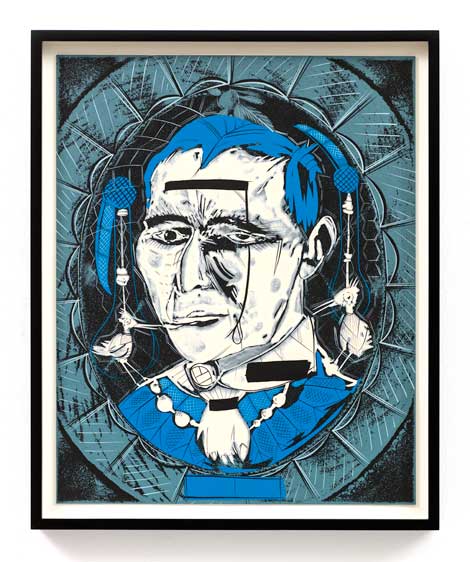

Lari Pittman, From “Twelve Fayum From a Late Western Imperium (After Hermenegildo Bustos),” 2013,

Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Lari Pittman

Pittman found early success showing with Rosamund Felsen Gallery in the ’80s, and went to Regen Projects in the ’90s. He has remained with them to this day, and is represented in New York by the Gladstone Gallery, a sister (or mother!) gallery if you will, of Regen Projects. He is collected by major museums all over the world and has a solo show up somewhere every five minutes. (Okay, maybe that’s an exaggeration.) What impresses me most about Pittman is his prolific output. He’s a hard-working productive artist, as his voluminous exhibition record proves.

On top of that, he is a professor at UCLA. He teaches both undergrad and grad students. Asked if students are more careerist than idealistic these days, Pittman takes a long pause before answering: “Let’s say it seems that it is harder for young artists to keep or maintain intact an identity-base as an artist unless there’s an external stimulus or approval. I do think that it’s important to have a professional identity, but that shouldn’t be equated with making money. Now it’s become synonymous. It pains me to see it, but it’s just a reality of advanced capitalism—a really ruthless system. You know, it’s hard to find identity without external approval.

“I find, especially for myself to this day, I love, absolutely love being an artist, I love being in my studio,” Pittman says enthusiastically, but then leans into me and says, “And I absolutely hate the art world.” We have a laugh at this together, and talk about how common this sentiment is among artists. “That’s just it. That’s why I’m so protective,” Pittman says. “Some people might think I’m snobby or a bit standoffish, and I am, to a certain degree. I really love being an artist, and this is something I decided I wanted to continue my entire life, and it would require some protection. And some sort of sense of self. Because the art world can be very cruel to artists, and artists can be very cruel to each other, and it isn’t just from the outside. The art world is a very nasty place.”

Fantasy Will Set You Free

I revisit Pittman’s studio one month later for a photo shoot. This time the door is left open and I have to holler to get him to come out. I like that, it seems to be a sign he’s now more comfortable with an Artillery invasion. I couldn’t wait to see how much progress he’s made with the flying carpet paintings.

For only a month’s work, the development was phenomenal. There must have been elves hiding in the nooks and crannies of the gallery, waiting for Pittman’s signal to come out and start working again. It’s seems impossible that he could have accomplished so much alone in a month’s time.

From anyone else’s point of view, the paintings looked finished. But knowing Pittman’s previous work, it could be anyone’s guess. Of the three paintings, Pittman said one was halfway done, and the other two three-quarters complete.

So, of course there will be more. That pleased me somehow. I wanted more. Way more. This is Lari Pittman! I want a bucket-load of more! I want more patterns, more scratches, more spraypaint, more guns, more spurts, more assholes, more disturbed nations. Then leave it all behind.

Lari, will you please save a place for me on your flying carpet?

Pittman’s show opens at Regen Projects on Sat., Nov. 9, 2013