“I’m a hypocrite,” Linda Vallejo says, referring to her latest series “Make ’Em All Mexican.” “I grew up on Fred Flintstone and Frank Sinatra. I’m all American.” She adds, “I think we are all hypocrites in one way or another. We all have our prejudices and judge each other needlessly based on color, class, education, et cetera. If we pretend that we don’t have these thoughts and feelings we’re lying to ourselves.”

I was hoping for this kind of frank conversation when we met for our interview at the Bergamot Station arts district in Santa Monica. We arrived at the same time and I spotted her walking toward the café wearing a floral dress, dangling beaded earrings and sunglasses—which I will come to find out she never removes (although they were transparent enough to see her piercing dark eyes). I commented upon how nice she looked. “I dressed up for you,” she replied.

We sat down to a light lunch and iced tea. Well into our conversation about skin pigment, I thrust my forearm toward hers, to compare our skin colors. I noted she’s not even particularly dark. She obliged with a laugh and acknowledged the Caucasian tradition of comparing tans. She expressed surprise that anybody would consider it a goal to get as dark as possible.

Vallejo grew up not knowing she was “different,” as she spent a good portion of her childhood in Germany. She did think that maybe she wasn’t very pretty, because she felt ignored in social situations. It was only when her family relocated to Montgomery, Georgia, during the mid-’60s—the height of our country’s Civil Rights movement—that she began to realize she was judged by the color of her skin. She was a young adolescent and had to deal with the conundrum of which water fountain to drink from or which bathroom to enter. “If I went to the ‘colored’ water fountain, would I get beat up, or the ‘white’ bathroom, the same situation?” Vallejo was right in the middle of it. She recollected that era with a heavy sigh and a swift hand swipe across her neck. Those were tough times for her.

Now her new body of work, “Make ’Em All Mexican,” addresses that period of her life in a roundabout way. “I think overall this [new series] is actually the culmination of 30 years of involvement in the Chicano indígena community of the United States, especially California, and after being involved in such a long period of cultural awareness, community awareness, aesthetic awareness.” Traditionally, Vallejo tells me, the Chicano-Mexicano artistic genre consists of painting and murals. She wanted to explore other genres and try other methods of art-making. She was teaching all over the U.S. at the time, which allowed her to visit numerous major museums across the country, where she saw a lot of repurposed work: taking an object that is already produced, then making art out of it, i.e., found art objects, readymades.

Vallejo asked herself, “What would happen if I made repurposed art from my cultural point of view?” She mused aloud, “I saw the work and asked myself, how come I’m not making work like that?” She was also able to do a lot of international travel. She visited the Pantheon, which gave her fresh inspiration. She started taking photos and manipulating them, adding newspaper clippings and other images, and called the series (which has never yet been shown) “Censored.”

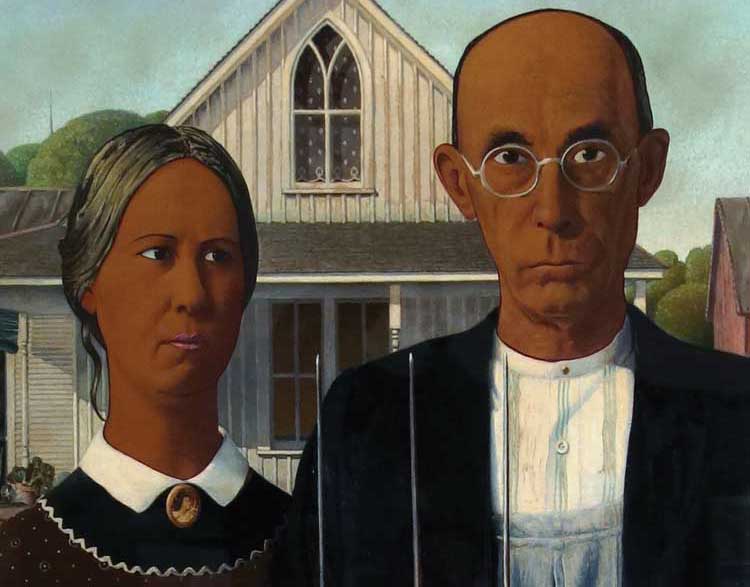

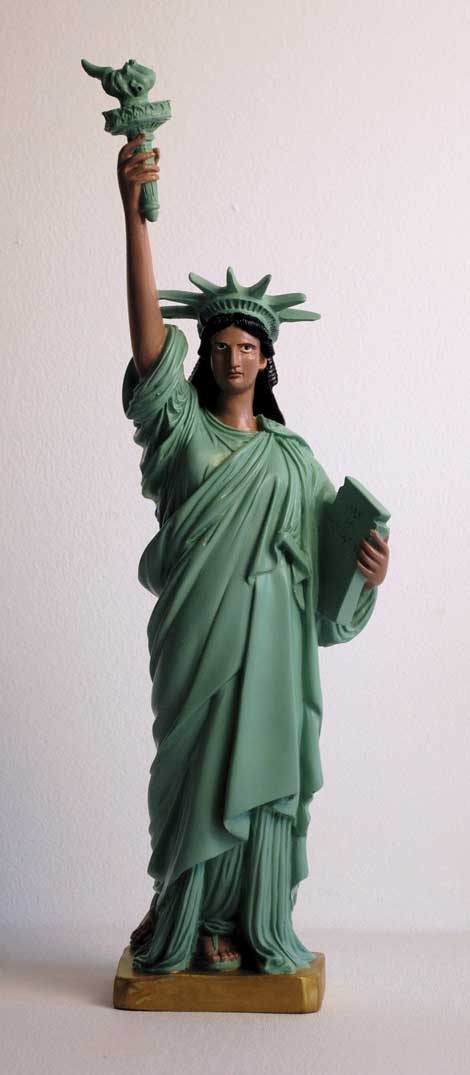

Vallejo went to a lot of secondhand stores looking for photographs for “Censored.” One day she saw the Dick and Jane primer (the book most American baby boomers grew up with as a reading tool). That’s when she had an epiphany: “I could paint them brown and make them Mexican.” She bought it on the spot and took it to her studio and “put gouache to it.” She didn’t stop there, collecting as many (kitschy or not) iconic images as possible. That would be the first piece in her series, all of the images—either photos or reproductions—being 2D. During one of her hunting and gathering excursions, a pair of salt and pepper shakers caught her attention. They were little pilgrims. “I said to myself, that’s fucked-up,” Vallejo recalls. After that it was no holds barred. Every object, trinket, figurine—they all entered her studio white, but left brown.

“But do you really want everyone to be Mexican?” I ask Vallejo. I mean, you could go to Mexico and see all the iconic imagery and it would be brown. But Vallejo doesn’t want to go to Mexico, she loves living in Los Angeles. She explains, “When you live in a culture where nothing looks like you, where nothing is [validating] your beauty, your intelligence, your potential, your contribution, what do you do with that? How do you function within that?” Vallejo adds, “It’s like being in corporate America, being surrounded by a bunch of guys. And you’re the only girl in the room. It’s lonely. You can never go into the men’s room. It’s exclusionary. It doesn’t feel right.”

When Vallejo added the part about exclusion for my benefit, making the comparison for a woman, I felt that it was a display of empathy. Vallejo’s “Make ’Em All Mexican” produced a knee-jerk reaction in me when I first saw the work at Avenue 50 Studio gallery in LA’s Highland Park. As a white person, I felt offended. The work seemed facile, even shallow. I also didn’t think painting Marilyn Monroe brown made any sort of point. I am a huge James Brown fan, but I wouldn’t want him white just because I’m white. But I realize I speak from a more privileged perspective and that perhaps it was me that didn’t have empathy.

I was prepared to simply write it off as the work of an angry Chicana who wanted to erase the white world, and, well, make ’em all Mexican. I tell Vallejo this, and she is open to my interpretation and not offended at all. She listens to me, but she wants to correct me when I ask if this series is a deep exploration of race. “I don’t want to focus specifically on the word race. The word race makes me a little nervous because I think it puts too fine a point on it,” she explains. “If I said this work is all about race, I think that would be oversimplifying it. It’s about relationships, it’s about the politics of color, the politics of class. I think it’s about inclusion and exclusion. It’s about self-image and self-worth, compassion and empathy, and it’s about what we share in cultures.”

But the work comes off as polemical, and perhaps a lot of people think like me. Vallejo responds, “It’s a strange double-edged sword. The work is interesting to the high-level artistic intelligentsia, but the market is afraid of it.” An ironic twist to her exhibiting this work is that institutions are eager to show the series, but galleries seem to steer clear, (she is affiliated with George Lawson Gallery in San Francisco and Bert Green Fine Art in Chicago). Her close colleagues tell her she shouldn’t do political art. Vallejo is fearless though, and is determined to continue her exploration with this body of work.

A lot of friends and family were able to attend her solo exhibition at the Museum of Art and History in Lancaster, California, on opening night. A poignant moment for her came when her brother was looking at Super Hombre (2014), a Superman bust painted a milk-chocolate brown. Her brother seemed to be in a trance as she approached him. He was almost teary-eyed, she recalls. She asked her brother to articulate what he was feeling. After a long silence, he uttered, “I finally belong.” That was an important moment for Vallejo, as she felt her art transcended what she had been hoping for with this series.

“I can be brown and be powerful. I can be brown and manly. I can be brown and be strong,” Vallejo says of her brother’s feelings. “So when he saw Superman brown, he thought, ‘Me too. I can save lives. People look up to me and I’m brave and I’m beautiful.’” She says this very passionately, then pauses adding with a chuckle, “Brown is beautiful. Brown is the new black.”

Vallejo has produced 200 pieces in three years. Is that enough, I ask her, what’s next? “Now it’s morphing. It’s morphing into paintings. It’s morphing into photography, possibly video. It’s based on the same topic, based on some of the same aesthetic issues. It’s becoming more personal in some cases.”

She’s eager to move in new directions. She’s started a new painting and is sticking with the color brown. “Let’s see what happens when I paint brown. Use paint. Enjoy brown.”

I realize now Vallejo doesn’t really want to make ’em all Mexican. What started as a joke actually produced a real dialogue. She works from the heart, as a real artist should. And she wants to explore issues that are important to her, like artists should do as well. She summed it up honestly and nicely, “I don’t have all the answers. I’m growing with this work.” This doesn’t sound hypocritical to me.