Death, destruction, strife and pollution—the pairing of Kris Kuksi’s and Preston Daniels’ variations of dark sensationalism transport us to their version of artistically-mediated Armageddon, with each creating unique and hauntingly extravagant objects. Kuksi’s baroque wall sculptures are windows onto apocalyptic scenes, using a narrative style of assemblage to critique war, and portray devastation and the rebirth of society atop the ashes. Daniels’ installation complements nicely while embracing “darkness” in a much more tactile and literal way, allowing zero buffer between the viewer and the thick black ooze claustrophobically dripping from the vast geometric shapes that engulf the second gallery.

Truly a master appropriator, Kuksi builds vastly intricate artworks using thousands of repurposed, modified and carefully articulated miniatures—whether from statues, toys or any other object globally sourced that finds its way to his rural Kansas studio. In a world where we stroll past art mid-stride, Kuksi’s work begs to be examined and explored at length, with an almost infinite amount of information residing within the minutia. Embedding Renaissance-style nudes, military figures and classic mythology into his creations, Kuksi acknowledges that which has come before—he just distorts it in a way that complements his own twisted fantasies.

While sculptural, Kuksi’s work embodies the junction at which art, image and violent narrative collide. Something akin to the method of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment—the artworks have a centralized story, but also dozens of sub-themes and characters subtly interacting with each other. The unspeakable horrors depicted are hidden amongst the sheer volume of imagery. Kuksi’s massive wall sculpture, Leda and the Swan (2014), exemplifies this unique style. The life-sized figure of Leda lies beneath a tree, surrounded by hundreds of other vignettes. A miniature world of scaffolding, construction and chaos is being built atop and around her reclining body—giving insight to the fact that evil is consuming what once represented high beauty. Explore closely and groupings of tiny severed heads can even be found suspended amid the tree leaves shading her.

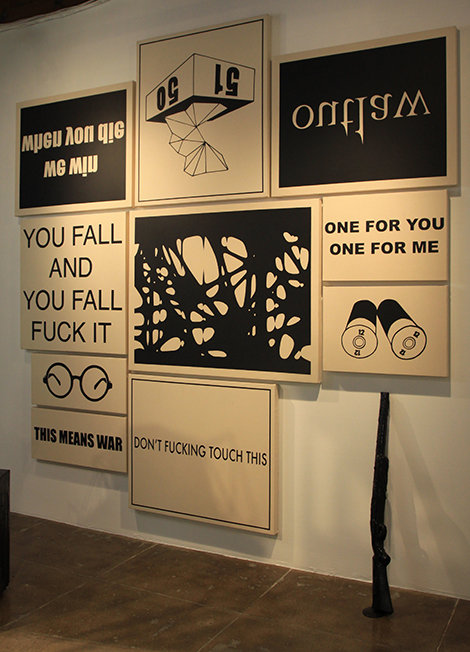

Compressed within the second gallery, Preston Daniels’ installation is an immersive and ominous environment. Jutting precariously from the walls and ceiling are minimalist forms of splendor—geometric structures containing fluorescent light fixtures. Covered in dark menacing goo, it is as if flawless works by Sol Lewitt and Dan Flavin have been encased in a millennia’s worth of grime, sludge and other effluences. Residing on the far wall is a cluster of text paintings, some legible and others with the lettering inverted. With phrases such as “WHEN YOU DIE WE WIN” and “ONE FOR YOU ONE FOR ME” (accompanied by imagery of two shotgun shells), the wall is an instruction manual for escaping this doomed ecosystem.

Too often, contemporary sculpture leaves us utterly disappointed, but this exhibition provides a reprieve from the norm. While psychologically menacing, these artworks embrace the wonder of destruction and the potential carnage contained within the human condition—all the while somehow making it look sexy as hell.

0 Comments