Offering a more complete picture of the artist than the one beloved in popular imagination, “Keith Haring: The Political Line,” at the de Young in San Francisco illuminates a more radical and shamanistic side that seems to be fuel and lifeblood for the playful and optimistic sensibility that garnered him such widespread appeal and recognition in the two decades prior to, and many since, his death in 1990. This Haring is more complex, a man with a desires and fears and deep concern for the world around him. For anyone that has dismissed Haring as lightweight or populist—whether for the pared-down silhouettes or sheer peppiness—this is the exhibition to see.

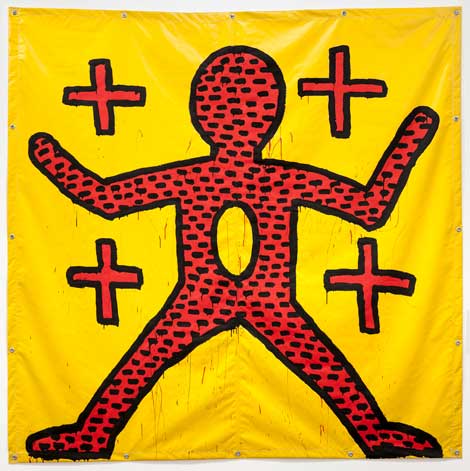

Keith Haring (1958–1990), Untitled, 1981, Private collection, courtesy of Museum der Moderne Salzburg, © 2014, Keith Haring Foundation

On a sunny afternoon in Golden Gate Park, visitors waited in long lines see “The Political Line,” guest curated by Dieter Bucchart with Julian Cox of the de Young. Among iconic dogs and dancers are images of lynching and castration, spaceship abductions and televisions cutting off heads, burning bibles, bacchanalian scenes, and a vast number of erect penises. The familiar dogs and dancers appear throughout, but in new and surprising contexts. In Untitled (1981) strong black lines depict a figure tumbling upside down into the snapping mouths of pointy-eared predator dogs on a page splattered with red spray paint that suggests blood and Pollock in equal parts. Throughout 130+ vibrant paintings, bold sketches, sculpture and memorabilia (including photos of Haring in the subway and diary pages), sticks impale hapless figures, knives plunge into bleeding worlds, and heads explode. If viewers were surprised, it didn’t show; families, teens, and people of all ages were game for this view of the artist, holding hands, snapping pictures and sketching.

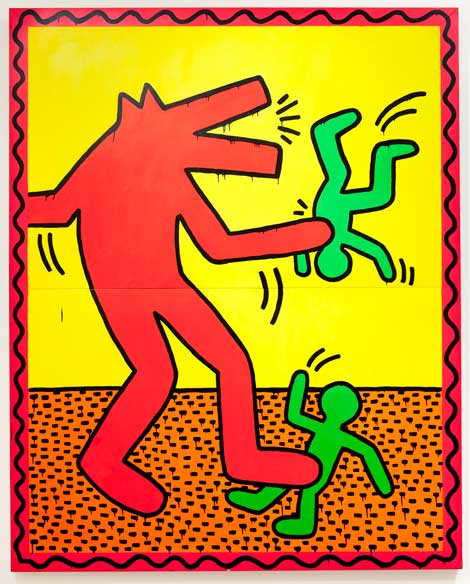

Keith Haring (1958–1990)

Untitled, 1988, Collection of the Keith Haring Foundation

© 2014, Keith Haring Foundation

Spanning a time period just shy of two decades, works address racism, homophobia, environmental abuse, materialism and the underbelly of technology. Fluid shifts in style and content show an artist engaged with issues that impact the world and also continually—hungrily—stretching to evolve his singular vision. The exhibition moves between gestural graphite lines, flat painted shapes and sinuous streams of paint at a speed evocative of the lighting fast on-the-fly subway drawings that introduced Haring to the world in the early ’80s. Whether from habit, predilection, or some mystical awareness of the precariousness of life, Haring maintained this rapid-fire pace throughout his too-short life, creating hundreds of seminal works, including more than 50 public projects in just six years (between 1982 and 1989) in cities around the world, many for charities or hospitals.

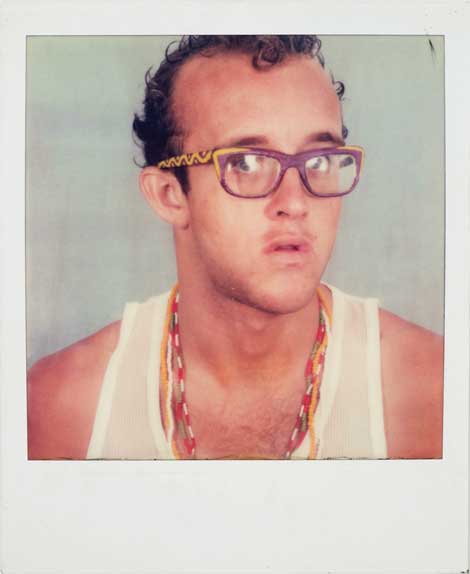

Keith Haring (1958–1990)

Untitled, October 1982, Collection of the Keith Haring Foundation

© 2014, Keith Haring Foundation

By the late ’80s, Haring’s work was so popular that knock-offs were as common as the work itself so another interesting aspect of “The Political Line” is the way it shows Haring’s thoughtfulness and depth as a painter. Large abstractions wink and nod at Lichtenstein, de Kooning and friends Basquiat and Warhol, while paintings covered in intricate, swirling lines trace orgiastic scenes in a fresh fusion of Bosch and Aboriginal art. The allover pattern of black lines dotted with yellow of Moses and the Burning Bush (1985) forms a mesmerizing nearly opaque screen over a blue and red picture of man and fire. The quick sketches, most with handwritten text, that make up Manhattan Penis Drawings for Steve Hicks (1978) comprise a smart, funny take on minimalist grids and conceptualist archives. Captions indicate a quirky taxonomy suggesting categories like place (“Drawing penises in front of the Museum of Modern Art,” “Drawing penises at Tiffany’s”), proportion, (“Actual size”) and play (“Misplaced Heads” for a sketch of penises with tips separated from shafts).

Keith Haring (1958–1990)

Untitled (Apartheid ), 1984, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

© 2014, Keith Haring Foundation

A wild fusion of aggression and fancy characterizes the virtuosic Untitled, September 25 (1985), a landscape divided between purple sky and yellow ground and dominated by a fleshy-peach beast with two identical mouths—one where expected, the other on its ass—both with bubblegum pink lips, Crest-strip-white teeth and forked, blood-red tongues. The upper mouth is framed by a silver-gray television while four tongues stretch in unison from the lower mouth, reaching through and around the orange-and-black patterned figure of a man, dangling scissors around his testicles. Thus ensnared, the figure clutches a wad of bright green bills (marked by an oval suggesting a zero) in one hand. With the other hand, he tosses bills at the beast, seemingly in desperation, but such is the hypnotic strangeness of this painting that an act of devotion is a possibility, too, if distant. The mythological monster—a collective nightmare of greedy capitalists, out-of-control media and the religious right—is vanquished, or at the very least deftly challenged, by the sheer power of its depiction. Surely, Haring will engage, enrage and ignite yet another generation.

ends February 16, 2015

“Keith Haring: The Political Line”

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, de Young

http://deyoung.famsf.org/

0 Comments