The residential valley neighborhood wasn’t what I was expecting when I went to Chas Smith’s studio for our interview. Big shade trees lined the wide boulevards of modest houses and neat lawns. Smith has been Paul McCarthy’s main art assistant for over a decade, and for some reason I was thinking the area would be trashier, near a remote woodsy area. I guess I was already typecasting Smith in my mind, imagining splattered ketchup and a wooden outhouse in the front.

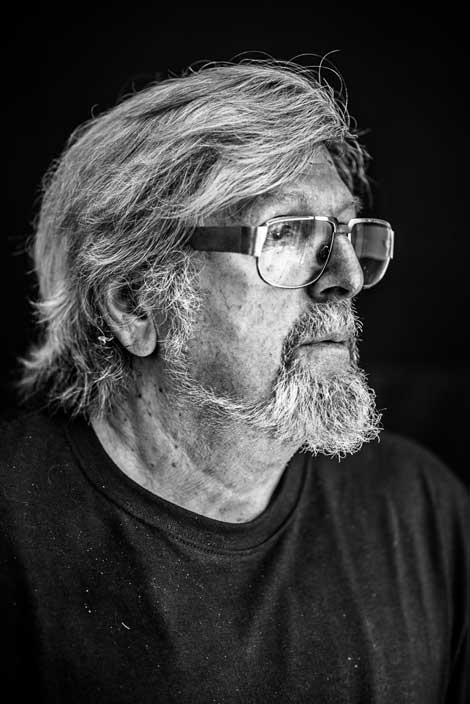

Smith greeted me as I peeped my head through the open door, calling out his name. He’s a tall, substantial bespectacled fellow, in his latter 60s, with white hair and a trimmed white beard. He plays steel guitar, and looks like he plays a steel guitar. He’s immediately gracious, offering me a cup of coffee, retracting his offer of milk, realizing there really wasn’t any milk (and perhaps never has been). He pours me a big cup of joe from the coffee maker, then we head through sliding glass doors that lead to the barnlike garage that is his machine shop. On our way I spy a forklift under a plastic cover on which leaves have gathered. He affirms that it still works and frequently is in use.

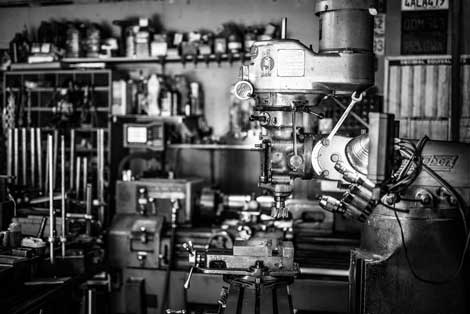

The machine shop is what anyone might imagine a machine shop looks like. There is a mill, a lathe, big hulking steel tables with saws and other sharp objects, with welders in the corner. There doesn’t appear to be any work in progress, but there isn’t any dust on the machinery either. Smith tells me how one of his lathes is so old that if anything breaks down, he would be “shit out of luck.” But can’t he just make the part, on the machine that he needs the part for, I naively ask?

Smith has spent many years in that shop working on other artists’ work. He was instrumental to many of the artworks in the now legendary 1992 MOCA LA “Helter Skelter” exhibit, working on Chris Burden’s massive Medusa’s Head, Nancy Rubin’s colossal sculpture of trailers and hot-water heaters, and McCarthy’s notorious installation, “The Garden.” That shop has seen some of the most famous contemporary sculptures in existence today.

Standing in the dark, fluorescent-lit room surrounded by the cold steel machines, with the aroma of grease and metal shavings in the air, I pictured Smith toiling away for hours, alone, making complex armatures for the complex artists. In fact, it’s rather ironic that Smith is the one acting most like the archetypal artist, working in solitude in the studio. The role reversal struck me.

After the tour of the machine shop we walk through the backyard where cacti and machine parts line a pathway leading to Smith’s music studio. One cactus has grown out of control, but stops exactly at the doorway. I ask Smith how he does that. He replies that he talks to it, and threatens it at the same time. That seems to work.

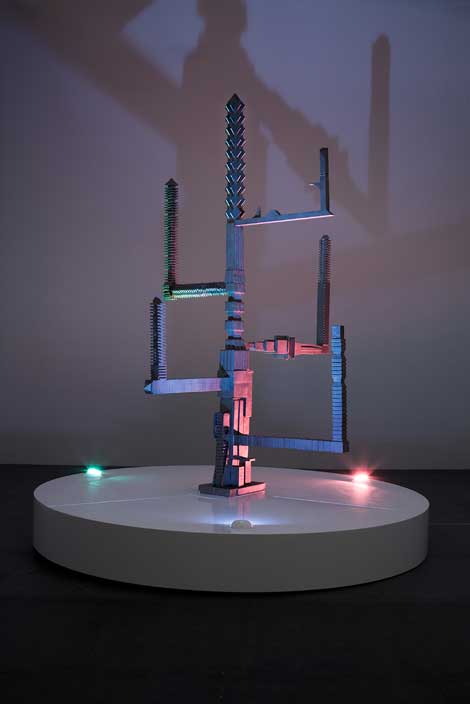

Smith is excited to show me his studio, where an array of musical instruments, or sound sculptures as they are sometimes referred to, are on display—all built from scratch by Smith. His policy is to make instruments only out of recycled material. One particular piece demonstrates this proviso quite nicely. It comprises eight saw blades aligned vertically, but cockeyed. He taps the blades and plays a little ditty. Then he goes to another instrument with steel tubes dangling like chimes and gently bangs out a horror flick soundtrack; I listen for a hair-raising scream in the background. The instruments are crammed in a tiny room, making it seem more of a showroom than a place to practice. There is a sound-recording studio in the next room; most of the equipment appears outdated. I would imagine any sound studio would be digital-only in this day and age. I don’t rub it in, but he did show me some digital recording equipment, just to let me know he doesn’t live entirely in the dark ages.

After seeing Smith’s two studios—reflecting the two sides of Smith (one: musician/composer, the other: welder/builder), we settle into the main house, where the living room has been converted into an office, the bedroom another studio, the kitchen serving more as place to keep cold beers and the bathroom functional, but not “female-proofed”—although he assures me there is toilet paper.

Smith grew up in New England in the ’60s. He tuned in and dropped outta Ithica College (actually he was expelled), “majoring in recreational pharmacology—a little too much LSD,” he unabashedly admits. His high school record was no different. He finally found his calling at his father’s much-too-early funeral. Smith recalls how the invited organist brought on a swelling of sorrow where “it became this collective experience of emotion, and everyone was crying. Then the organist brought us all back.” That’s when he realized that music would become his life.

Smith quickly got himself enrolled in Berklee College of Music in Boston—where he faked his way to an entry audition to play piano (he had three weeks to learn piano)—he was stopped midway in his performance by an irate faculty audience, yelling how dare he waste their time. Somehow he convinced them to let him play guitar instead. His scheme worked, but he dropped out after six months. As Smith recalls, he “just didn’t dig jazz music. That’s all.”

Smith then takes me on a journey of how he ended up at CalArts—a story worthy of a Hunter S. Thompson journal entry. His use of profanity is so seamless that I would never have guessed that he uses the F-word practically every other sentence. We find ourselves discussing Windowpane acid versus Purple Haze. Smith rhapsodizes, “The parties were off the scale, everything you heard was true.” He received his MFA from CalArts in Music Composition in 1975.

While all the partying was going on, that last year of school Smith was engaged in some extra-curricular activity. By night he attended the College of the Canyons to get his LA City certification for structural steel. Music is everything to Smith, but welding comes close. He lights up when he talks about it: “I love welding,” he pauses, then leans in, tapping his forehead, “In the little window in my hood—my welding hood—I’ve been looking at that pinpoint of white light for 40 years, and I’ve never gotten tired of looking at it. In that white light, magic happens.”

Smith realized he had to make money in order to support his exotic taste for creating unique instruments and experimental music. He found a place in the film industry composing and performing film scores, such as American Beauty and The Shawshank Redemption. He’s owned a record label and made numerous recordings and CDs. He’s been a member of many bands and enjoys a musical solo career as well. He also welds and builds things, so he was employable in the film industry in that capacity (working in special effects) and found himself building things for artists as well.

That’s where Paul McCarthy comes in. The two go way back in many capacities: work, art, performance, music and play. Smith has known McCarthy since the ’70s and, oddly enough, they worked together on the first Star Trek movie, doing their manly things such as welding and building. Many sculptors work in construction for their day jobs, and that’s precisely what McCarthy and Smith did. Their paths also crossed as they were with a group of musicians that played at art openings. McCarthy as been his “primary employer for the last decade,” Smith says. And how does that make you feel, I ask like a therapist. Smith really doesn’t think much of the role he might play being an assistant to many art stars. He considers it a job, and the good part is he gets paid for working in an environment that he loves.

Smith says McCarthy’s status in the art world makes many assistants necessary: “To play on that level, you have to have a crew.” By way of example, he cites McCarthy’s exhibition in Germany several years back: “It was fuckin’ huge!” he exclaims. “The thing I built was the size of a 2-story house—and everything moved. One man cannot fill that building.” Smith is referring to McCarthy and collaborator son Damon’s Haus der Kunst exhibition, “Pirates Caribbean,” in Munich in 2005.

Smith darts to his computer to show me Underwater World, one of four installations from the Munich show. He brings up a video of the kinetic sculpture, which resembles a moving ship, mainly to illustrate the scale of it. Smith built the entire sculpture, piece by piece, in his machine shop. It’s unbelievable when you realize the gigantic size of the piece. They assembled it at McCarthy’s studio in Baldwin Park and it ended up being 21,000 pounds of steel. He also built the mechanics of the ship-like sculpture, to make it rock as if at sea—all this from a foam core model consisting of a few basic shapes.

That machine shop is also Smith’s studio for his own work, where he built and designed a three-neck steel guitar he calls lovingly “Guitarzilla.” How might artists feel when spending time on another’s work, knowing what could be accomplished if they were spending that much time on their own art?

Smith acknowledges and doesn’t deny that he does develop a personal connection with the work, especially when it’s like Underwater World, where he constructs every inch, from start to finish. But it’s still not like creating his own work, he maintains. “Left to my own devices, I would never build that. I would build a guitar. It would have chrome, pin-striping, it’s going to have anodizing.” He has absolutely no problem with recognizing the authorship of the artwork, no matter who does the manufacturing.

To further explain the position of artists’ assistants, he makes the comparison to a studio musician being hired to play a part in a song. “So I show up and play a solo—not my song, your song. My solo, your song. What you do is you appropriate my art for your art. You appropriate my skills for your art, and I’m okay with that.”

We drift into conversation about a few other artists he’s worked with, like the late Mike Kelley. He worked on one of Kelley’s last installations, a piece from the “Kandor” series. Smith pauses, then wistfully says, “He got on the bus. You get on that bus, you don’t get off.” At that point, Kelley was on top. But that meant huge commissions, huge commitments, huge pressure. Smith saw it all up close. “He had 45 minutes, that month, to talk about a $300,000 sculpture. About what he wanted me to do, how he wanted me to do it. Afterwards I’m talking to Paul [McCarthy] and telling him about Kelley. I said, ‘He doesn’t own his life.’ McCarthy goes, ‘Oh yeah. We sold it. We sold our lives. I’m hanging on a rope outside of an airplane. I look to see what the pilot is doing—there is no pilot.’” Smith pauses again, then repeats, “Yeah, you get on that bus, you don’t get off. Do I want to get on that bus? No, I like where I am.”

Smith told this story with an air of sadness and caution. At that point, aren’t you just working for the man? Is that what most art stars are doing today? Churning out a product in order to fulfill the supply and demand at the dealer’s? Or their collectors (so they can turn around and flip it)? Isn’t it like any other job now? Sure, maybe McCarthy is the director, the man at the helm, but is it worth it?

“If [McCarthy] sells a fifth of what he makes, I would be surprised. It’s about selling the piece, it’s about putting on the show.” Smith adds that if the artist doesn’t sell the piece, the artist doesn’t get to make another. “What it looks like to me, and I don’t want to piss off anyone, but it looks like to me, you have the big pieces, and the little pieces pay for the big pieces. You can’t do the big pieces if you don’t sell the little pieces.”

Some artists can’t handle it. They lose control, and then they might wonder where is that spark, that drive, that magic—the magic that Smith was talking about—that white spot when he’s welding. Smith said he never tires of it, for over 40 years now. I wonder how many successful artists today can say that.