From its troubled (I almost want to say stuttering) conception and creation, through its earliest publication – barely stitched together, edited, revised, corrected, re-edited – Melville’s Billy Budd is steeped in ambiguity – ambiguities integral to the dramatic and psychological tensions that radiate off the page. The definitive mid-century edition with its three slightly discordant ‘postscript’ chapters could only confirm and compound such ambiguities. But in the great tradition of “When the truth becomes legend, print the truth,” dramatists couldn’t wait for such (ir)resolution; and the first adaptations appeared more than a decade earlier, just after World War II. The play made its way to these shores and a production opened on Broadway the same year (1951) Benjamin Britten’s opera, with a libretto co-written by E. M. Forster, opened at Covent Garden. Master of tonal and thematic ambiguity, the austere motive played against waves of lush lyricism, and a literary and psychological scope unrivalled amongst his contemporaries, Britten might have been ideally suited to the challenge of setting this drama to an operatic score.

The music has lost none of its power over the years, its resonance not simply with Melville’s novella, but its musical antecedents – Verdi (e.g., Othello), Wagner, and especially Mahler – underscoring its durable appeal. Britten, like Wagner, is a master of layering motives, with a penchant for a chromaticism of lights and darks, bright cadences and clarion chords laid over tension freighted choruses and keening laments. We’re immersed in the chromatics from the start – also the chromatics of memory, of conscience, of innocence and evil, dubious motives, and implacable law and justice.

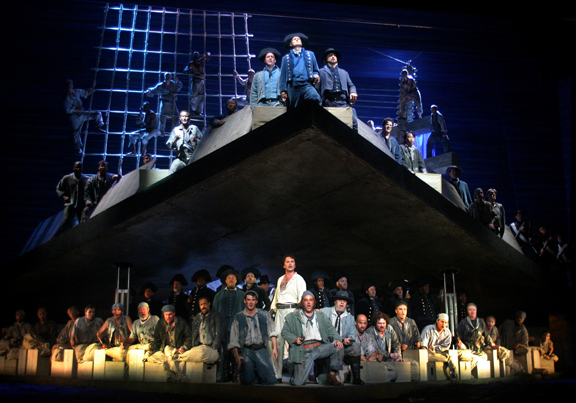

Motives are not just layered here, but boxed or bottled up within each other. Melville and Britten both explore notions of flaw, corruption, perversity in literal, physical terms. The cabins and galleys of the ship are contrasted with the open deck and beyond that, the suggestion of the open sea; darkness or dimly lit spaces with the sun-lit open air and sun-dazzled waves. The challenge for any production is to push and pull the audience’s focus between these dramatic spaces – focusing the heat and tension of dramatic developments, while keeping the whole moving on deck and on the waves.

The still moments stand out best when the rest of the opera is kept in motion. The prologue is one such sustained moment – and production designer Francesca Zambello and lighting designer Alan Burrett make the most of it, plotting out a stark gangplank of light eliding into darkness in the current Los Angeles Opera revival of her 13 year-old production. It is one of the most effective moments in the production. (Richard Croft is excellent here and throughout as the Captain, Starry Vere).

But with the exception of a few brief ‘action’ sequences in the drama (e.g., Budd’s (Liam Bonner) impressment; the Indomitable’s engagement with a French vessel; Budd’s confrontations and execution), the production suffers from an essentially static presentation. The directors and choreographers (were there any?) might have taken a few ideas from Broadway itself. The strength of the choral sections would only be underscored by a dynamically moving company of sailors. And notwithstanding the choral strength, you want that kind of visual enrichment in a setting where largely atonal recitative lines or airs melt away into the choral and orchestral backdrops. This brings up what might be my only reservation about the Britten score, which otherwise stands with his best: the fact that the principal arias and recitatives recede beneath as much as they stand out of the orchestral textures – an aspect that, almost 65 years later, now seems like a concession to mid-century operatic convention. (It’s as if for a time, composers had so distanced themselves from the merest hint of lyricism in the composition of operatic and art song, that they’d acquired a wholesale mistrust of the melodic. I sometimes wonder if there is some parallel here to anti-aesthetic tendencies in the visual arts.)

Opera Buddy thought the homoerotics of the story should have been given more play (gee, you’d think the port-to-starboard beefcake would be enough, but nooooo….). My own feeling was that Claggart’s (Greer Grimsley) scenes should have been given more emphasis, especially his aria at the end of the first act. This is a crucial part of the opera – dramatically, harmonically, where soaring, ascending lines in E or B flat major turn (with the gathering darkness on board) to Claggart’s ‘character’ F minor key. The entire moral and emotional spectrum is played here and we need to see, hear and feel it. What we don’t need to see is a complex universe of moral, political and emotional dimensions reduced to a cookie-cutter (which, I guess, here means essentially early Christian) iconography. It’s plain this is something more than a corruption and redemption narrative – so do we really need to see Billy hanging, crucifixion-style, on a mast? What compels us to revisit Budd again and again is not simply a story of innocence and corruption, repression and depravity, but an entire infernal (and internal) machinery of public social order and private emotional chaos. It’s not a ‘Jesus’ story; it’s a ‘Cain and Abel’ story. Siblinghood may be powerful; it’s also a little fraught; we’re not endowed or ‘flawed’ equally; and like Budd, we don’t always get to choose our shipmates.

If the Zambello production misses this, the opera and story nevertheless seem more timely than ever. Budd’s send-off to his old ship, “Good-bye old Rights of Man!” seems to be a constant refrain. Returning to Vere’s final moments, my thoughts turned to that familiar paraphrase of one of Burke’s famous speeches, “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.” Our own walk down the final gangplank will likely be less starry than Vere’s.

0 Comments