Piggybacking on Kim Stringfellow’s recent successful documentary, exhibition, and publication—JACKRABBIT HOMESTEAD: Tracing the Small Tract Act in the Southern California Landscape—Flora Kao explores and examines remnants of abandoned homes in the Mojave desert, the residual evidence of life left over from the rush of the Small Tract Act of 1938.

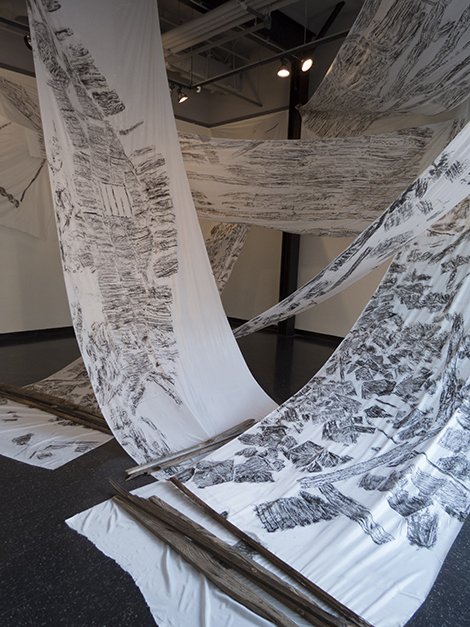

Though Kao’s background in environmental science and public policy suggest that her interest in the homestead movement may come from an anthropological standpoint, often her artwork has been imbued with an interest in the dissonance between humans and nature as well as our dislocation—and it shows in her newest work. Her installation at Grand Central Art Center, Wind House, Abode That a Breath Effaced, is a nostalgic and romanticized look at a treasured monument of a shattered and nearly destroyed home in a series of delicate and careful rubbings of the surface, as it lay in pieces in the desert. These rubbings, made on long panels of silk, further suggest the delicacy of the forgotten home she calls the “Wind House“ with her material choice. Set like patterns on the silky sails, the rubbings hang gently crossing one another in the exhibition space, feminine and transient. Breathtaking, the visual aspect of the installation draws you into the space even before you know what you’re looking at.

Though Kao’s concept isn’t unique, her approach feels genuine. Born in Taiwan in the mid-’70s Kao grew up between Houston and Taipei, and continued to live and work all over the globe for years before settling in Los Angeles in 2004. Her artwork explores her struggle with cultural identity, being a transplant, what it means to be detached and disassociated, seemingly fascinated with the notion of belonging.

Intrigued by the psychological effects of architectural spaces in everyday life, Kao plays with nostalgia and memory in her work. Her examination of the Wind House propels a viewer’s internal awareness and definition of home, as well as our constant yearning for control, constructing coping devices when home is absent or destroyed, and bringing attention to our mortality.

Humans share a collective yearning for a home—whether that home be cultural, emotional or physical. As such, the decay or disappearance of any kind of ‘home’ can be heartbreaking. Though much of contemporary artwork revels in clean and emotionless critical examination of our surroundings, it often lacks a connection to this idea. Kao takes an intimate route, exploring emotional evidence of the search for home and identity and finding a way to investigate these concepts.

Kao’s work shows contemplation and inspires thoughtfulness in its viewers. Because the installation is shown as remnants of her own experience at the Wind House, it feels personal, but that attachment and experience make it all the more interesting. A description accompanying the work is pertinent to understanding it; such didactics can be common for conceptual and ephemeral works, but Kao’s language reads like a private poem, providing an even more intimate gravity.