Fans of Art Spiegelman’s seminal graphic novel Maus can be forgiven for writing off Spiegelman as a one-hit wonder. After all, before producing the two volumes of the Holocaust memoir, which almost single-handedly turned the lowly comic book into a serious literary form, Spiegelman was a little-known creative consultant for the Topps Candy Company who moonlighted as a member of the Underground Comix movement. In the two decades since Maus, which won a special Pulitzer Prize in 1992, Spiegelman’s graphic novels have failed to live up to the promise of his breakout hit.

But a fascinating retrospective of Spiegelman’s work explodes this assumption, making a convincing case for Spiegelman as a brilliant visual polemicist and surprisingly avant-garde artist who for nearly half a century has twisted popular visual art forms to subversive ends.

“Co-Mix: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics and Scraps,” the first major exhibit of Spiegelman’s work since a 1992 show of Maus at the New York MOMA, begins with a series of gag trading cards he created for Topps, where Spiegelman worked for more than two decades. The Wacky Packages cards, which riff on popular consumer products (a box of Wheaties cereal is reimagined as “Weakies” and so on), and the later Garbage Pail Kids stickers, which satirize the cloying Cabbage Patch dolls, harness an antic Mad magazine–style comic sensibility to 1960s anti-consumerist political bent. The results are brilliant—sharp, funny miniature panels of visual invective that function as pocket-size Andy Warhol pop art paintings for nine-year-olds.

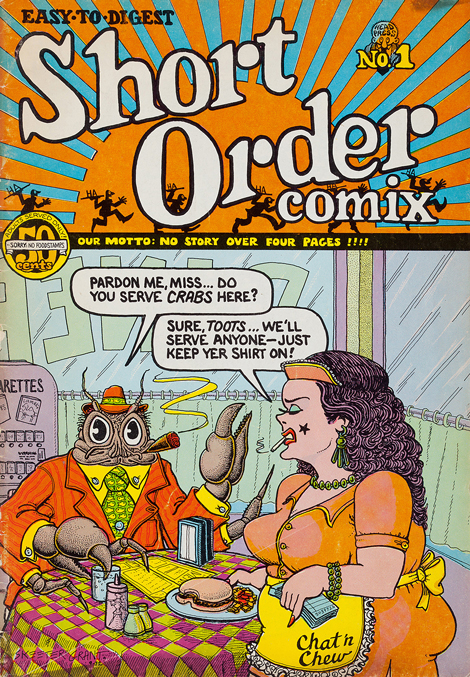

By displaying the bubblegum cards alongside the Underground Comix Spiegelman was creating at the same time he was working for Topps, the exhibit shows how his early hippie comics informed his coyly subversive commercial work, and vice versa. More importantly, these early works demonstrate how Spiegelman digested all manner of popular visual art, from Mad magazine gag panels to superhero comics, and refashioned them to more openly political (and often more personal) ends. From there, as the “Co-Mix” show makes clear, it is but a short conceptual step to Maus, a memoir of Spiegelman’s parents’ survival of Nazi pogroms and of Auschwitz reimagined as a sort of high-art “Tom and Jerry” cartoon, with the Jews as mice and the Germans as cats.

As is to be expected of any Spiegelman retrospective, Maus takes center stage in “Co-Mix,” with an entire room given over to the two-volume graphic novel that is sure to be Spiegelman’s most lasting work. The exhibit, designed in part by the artist himself, displays every page from Maus, along with dozens of sketches and preparatory drawings. The effect is grand, and also a bit demanding, since all but a few of the drawings are presented at their original size, forcing the viewer to stand inches from the wall and read the book panel by panel.

More successful, and in some ways more illuminating to those already familiar with Maus, are the rooms devoted to Spiegelman’s later work, especially his New Yorker magazine covers. The most visually arresting of these is the iconic black-on-black “Ground Zero,” depicting the missing Twin Towers, published weeks after the 9/11 attacks. Just as startling, though, is “Valentine’s Day,” showing a Hasidic Jewish man kissing a black woman, published in 1993 while the city was still recovering from the Crown Heights riots, three days of violence and looting that pitted Brooklyn’s Orthodox Jews against their African-American neighbors.

As with the Topps trading cards, the power of these images flows as much from their context as from their visual imagery. The Wacky Packages were not made to be displayed in a museum gallery but in the supermarkets where the products that the cards parodied were sold. To adult sensibilities, the sight gags and puns may sound like groaners, but to a nine-year-old boy shopping with his mom in 1974, Spiegelman’s cards depicting “Crust” toothpaste and “Jail-O” functioned as a critique of the very consumer culture into which the kid was being indoctrinated.

The New Yorker covers carry this cultural critique into more sophisticated, racially fraught terrain. In New York City, the New Yorker is the voice of the Upper West Side liberal establishment, which had recoiled at the racial violence out in distant Brooklyn, so Spiegelman’s Valentine’s Day cover, with its deliberately shocking depiction of interracial love, served as a provocation to white liberals, saying in effect, “You think they’re racist—what about you?”

Some of the subversive flavor of these images is inevitably lost when they appear on museum walls, but the thoughtful layout of the exhibit, along with informative wall text in each gallery, help the viewer understand the original context. And in the end, Spiegelman’s work, visually rich, politically radical, equally at home with the profundities of history and low-minded crotch shots, speaks for itself.