The overt theme of “Damage Control: Art and Destruction since 1950,” curated by Terry Brougher and Russell Ferguson, is the presence of destructive force(s) in art since World War II—a trajectory of investigation whose origins in the war (especially its nuclear finale and Holocaust coda) are apparent and compelling to all observers. A sense of destruction-once-removed pervades “Damage Control,” beginning as it does with photo-documentations of ’60s actions and, more tellingly, books and magazine articles about Hiroshima. And more than once, the mesmerizing footage of a burning World Trade Center provides the heart of a contemporary artist’s anguished fantasy.

The subliminal theme here, however, is that art, as a process of representation, upends the grasp on life we attain through mass media, while at the same time insisting that mediated depiction is the only authentic experience we have.

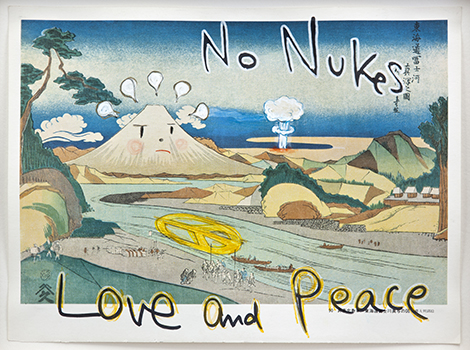

In both the 1950s and ’60s, artists struggled to harness or at least direct destructive forces in gestures of annihilation and decay. Jean Tinguely made self-immolating machines, Yoko Ono guided her readers and audiences into almost dreamlike destructive rituals, Rafael Montañez Ortiz enacted happenings of mattress burnings and piano axings, and Gustav Metzger, high priest of the Destruction In Art movement, applied hydrochloric acid to canvas. But rarely did these artists’ gestures result in objects that retained—mutilated as they were—a tragic self-possession (Robert Rauschenberg’s 1953 Erased de Kooning Drawing being a poignant exception).

Other artists, many of them friends and colleagues of Metzger, Ono, et. al., did produce artwork that inhered the destruction to which they were subject; these were surveyed in Paul Schimmel’s 2012–13 valedictory MOCA show, “Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void, 1949–62.” As if to critique Schimmel’s point while extending it into the current era, curators Brougher and Ferguson involve themselves less with damaged goods than with gestures of destruction, theatrical remains, and scenes of damage. Those scenes often play out in carefully fabricated structures or camera-captured circumstances, whether the late-’60s photos of Swiss car wrecks by Urs Odermatt or destruction-staged-for-videos by Dara Birnbaum and Mircea Cantor, Thomas Ruff’s news-photo-like shots of collapsing buildings, or paintings clearly based on news photos by Vija Celmins, Jack Goldstein, Monica Bonvicini, and, inevitably, Andy Warhol.

Ed Ruscha, “The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire,” 1965–1968. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC.

One can play the “what’s missing” game with such an ambitious survey. Didn’t Piero Manzoni do anything apropos? Where are the Viennese Actionists, masters of bloody mayhem before the lens as well as the audience? On the other hand, the concept of “destruction” blossoms among contemporary artists as various as Steve McQueen, Juan Muñoz, Douglas Gordon and Mona Hatoum.

Destruction In Art was a movement, as “Damage Control” documents; but now, among artists whose world will end with a whimper and not a bang, it’s a preoccupation.