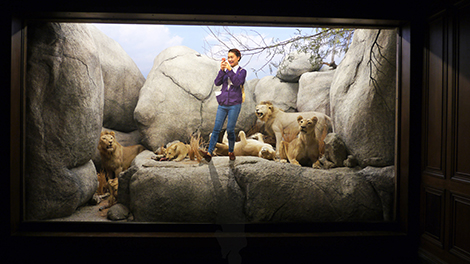

The series of relatively small digital photomontages Clayton Campbell has assembled under the rubric “Wild Kingdom” satirize social habits—on more than just the most evident levels. The images, all horizontal, consist of wildlife dioramas, the kind that fill corridor after corridor of natural history museums and seem never to go out of style—except that here, they have been invaded by visiting humans, not standing before the dioramas, but in them. It is the dream of many a child, of course, to crawl into these life-size three-dimensional friezes. But, whether plopped into a veldt, a desert, or a jungle, Campbell’s Homo sapiens (taken by the artist himself on the sly) are singularly incongruous. They’re not safari tourists, much less indigenous people, but you-and-I folks in casual or business suits—every last one of them yakking away on his or her cell phone. No, I take that back; every last one of them is doing something with a cell, whether talking on it, using it to shoot a scene or a selfie, or aiming it at another dropped-in person who’s mugging for the pocket camera.

The dioramas Campbell has documented here evoke spaces of great beauty and contain creatures of similar wonder. Were you one of the people Campbell has inserted into such spaces, one thinks, you’d do nothing but gape at the natural spectacle around you, too awed to reach for your apparatus. But get real: wouldn’t you whip out your iPhone or Android and start clicking away, so you could share the scene with everyone on Instagram and to assure yourself that You Were There? In fact, Facebook abounds with pix of people popping pix when they should be staring at and studying the reasons for being where they are. But these reasons are usually artworks or urban monuments (the cluster of teens texting away in front of Rembrandt’s Night Watch has become a meme). Nature, it would seem, abhors a BlackBerry even more than it does a vacuum.

Besides ribbing us about our cell phone addiction, Campbell’s neo-Dada superpositions point at the conceptual remoteness of the physically remote, inferring that our alienation from nature allows us to despoil it from afar. To an extent they also mock Campbell’s whole endeavor itself, as well as the technology that makes them—and cell phone photography—possible. After all, Campbell captured his phone-wielders with his own phone. And then he shoehorned them improbably into spaces where they don’t belong, legally (natural history dioramas) or contextually (seemingly untouched natural sites). The insertions themselves are awkward, the figures squeezed in among the lions and the ostriches, the seams of their montage showing. Keeping his production values modest—not tacky but not slick, either—Campbell piles the ludicrous on the poignant, pathos on bathos, in a hall-of-mirrors satire that keeps unfolding long after you’ve looked at his artworks—and maybe taken a selfie with them.