Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Christopher Michno

-

CLIMATE CONSCIOUS

Artists Advocate for Carbon ReductionsArt sector efforts to decarbonize have been highly visible over the past three years as galleries and artists have publicly pledged concerted action to reduce exhibition-related emissions: Nonprofit advocacy groups like Gallery Climate Coalition, Art + Climate Action and Julia’s Bicycle have launched campaigns and provided tools to support change in art sector practices. These developments are important steps for an industry driven by wealth and privilege that, according to carbon analyst and Gallery Climate Coalition advisor

Danny Chivers, generates disproportionately higher emissions than comparably scaled market sectors.Jenny Kendler, a founding member of Artists Commit, sees this as a critical moment. “What we need now, more than ever,” the Chicago-based artist says, “is to change culture.” The need for urgent measures is underscored by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) most recent report, which notes that the window for meaningful action is rapidly closing. In the words of UN secretary-general António Guterres: “The climate time bomb is ticking.”

Kendler, who was the first Natural Resources Defense Council Artist-in-Residence, has long made climate action a cornerstone of her art practice and, more broadly, her engagement with the world. Long before COVID and the ubiquity of Zoom, she limited her air travel, agreeing to give artist talks only when Skype was an option. “This is a systemic issue,” she emphasizes, “We need each and every artist to be a part of the global climate movement, in whatever ways they have capacity to do so.”

To be a partner for change, she says, means “making choices that benefit life as a whole, rather than working toward personal or short-term gains, status or purely economic benefit.”

Jenny Kendler, “Dear Earth” (21 Jun. –3 Sep. 2023), installation view. Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy of The Hayward Gallery. Kendler advocates considering an artwork’s lifecycle at its inception. While this can mean thinking about the type of materials that compose the work—Kendler prefers working with recycled or ephemeral materials—equally important, she notes, is how it’s “produced and transported, where it goes after it is exhibited, and how capital flows into and out of the project.” Her installation Birds Watching III, for example, which was on view this summer in the Hayward Gallery’s ecology-oriented exhibition “Dear Earth,” was fabricated entirely with recyclable materials. The work will travel to the London Zoo to raise awareness about the zoo’s conservation efforts with critically endangered birds. After that, she hopes to find a permanent home for it and plans to use the proceeds for climate and conservation work.

Debra Scacco, an artist, curator and organizing member of Artists Commit, believes that artists are ideally positioned to introduce climate-conscious practices when working with institutions. Gallery, museum and nonprofit staff may not feel empowered to address climate, she says, but “if we consistently present this as a serious concern and, where appropriate, a part of the work, host venues will generally sign on in some way.”

A transplant from London, Scacco moved to Los Angeles in 2012 and quickly focused her art practice on the ecology of the Los Angeles River. In 2017, she founded Air, a residency that allowed artists to pose questions about specific climate challenges and engage with “systems that require critical change.”

Air worked in collaboration with Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator (LACI), which hosted a series of residency exhibitions throughout 2021. Air’s culminating exhibition, “Song of the Cicada,” at Honor Fraser Gallery presented artists’ findings on research, ranging from wetlands habitats, toxic manufacturing byproducts and climate impacts on natural systems.

“In my own work, I aim to connect each exhibition or event with on-the-ground environmental justice work,” Scacco says. This past fall, she curated “Confluence,” an exhibition focused on the LA River, at Track 16 Gallery. Each artist was asked to share the work of an environmental organization supporting the LA River. Gestures like these, she says, invite viewers to engage with climate work through their engagement with the exhibition.

Installation view of “Debra Scacco: Confluence,” 2022. Courtesy of the artist. In October, Scacco and Joel Garcia, an Indigenous artist (Huichol) and organizer, will partner with Fulcrum Arts to present Procession, a large-scale performance and civic activation. The project reframes the history of the Los Angeles River and the violence enacted on its ecosystems through colonization. Culminating in processions along the river’s former floodplain in Los Angeles State Historic Park, Procession identifies the river by its Tongva name, Paayme Paxaayt and will gather “stories of how different cultures utilize the river and how channelization impacts culture and legacy.”

Collaborative efforts to decarbonize the art sector are promising. “It is the conversations and collaborations that are happening across the sector that give me the most hope,” says Chivers, citing discussions to rethink “often over-strict” storage standards that drive energy consumption, art fair expectations for travel and shipping, and how institutions can thrive while cutting emissions by at least half.

These issues however, can’t be separated from social justice questions. Scacco makes a point that “the art world is a space of outsized privilege and waste while artists and art workers often struggle to make a living wage,” which she says makes the current moment an opportunity to create a new paradigm.

Cultural organizations have the potential to exert outsized influence in discussions over climate solutions, but this relies on credibly addressing their own emissions. In a global context in which public pledges often supersede actions, establishing credibility will also require institutions to develop transparent, verifiable protocols.

-

Book Review: A Measured Coolness

Building + Becoming by Amir ZakiBuilding + Becoming

By Amir Zaki

272 pages

X Artists’ Books and DoppelHouse PressThe works of Amir Zaki subtly subverts analog photography’s long-held truth claims. His photography, surveyed in the newly published artist book Building + Becoming, addresses the artist’s digital manipulation and, setting aside the medium’s presumed objectivity and fidelity to representation, invites the question, “to what end”?

Illuminated by two texts, “Stealing Light,” a conversation with Corrina Peipon, and “Addition by Subtraction,” an essay by Jennifer Ashton and Walter Benn Michaels, Building + Becoming explores Zaki’s formation as an artist, touches briefly on biographical notes and artistic lineage and examines his process while engaging in critical dialog. Ashton and Michaels also analyze the technological and post-production practices integral to Zaki’s images. At the core of their inquiry is the apparent contradiction in his claim of the Modernist tradition, via Edward Weston, and his use of a Gigapan device, which enables him to take a series of adjacent photos and stitch them together with software, resulting in works that defy the singular perspective associated with Modernist photography.

Computational imaging—to paraphrase a definition given by researcher and computational photography pioneer Marc Levoy, the use of computational methods to produce photographs that could not have been taken by a traditional camera—presents an alternate framework for considering Zaki’s technology-assisted creation of large-scale, information-saturated photographs.

The monograph is full of meticulously printed photographs that are just as beguiling and seductive as I know them to be in person, though on a reduced scale. One of the notions I have harbored—a notion the artist sidestepped when I interviewed him in 2019 about his “Empty Vessel” series (photos of California skateparks and broken ceramic vessels)—is that his work offers images of iconic California settings, which are complicated by the subtle, and sometimes not so subtle, alterations introduced through post-production editing.

In his conversation with Peipon, Zaki rejects what he calls the cynicism, hollowness and political and moralistic overtones of postmodernism. Though this description lacks definition, there is a point there about work that delivers straightforward political punchlines rather than examining the complexities and apparent contradictions of something, or engaging in open-ended inquiry. But inherent in any conversation on whether politics should influence art, or vice versa, is the question of what art can do, or what one wants their work to do.

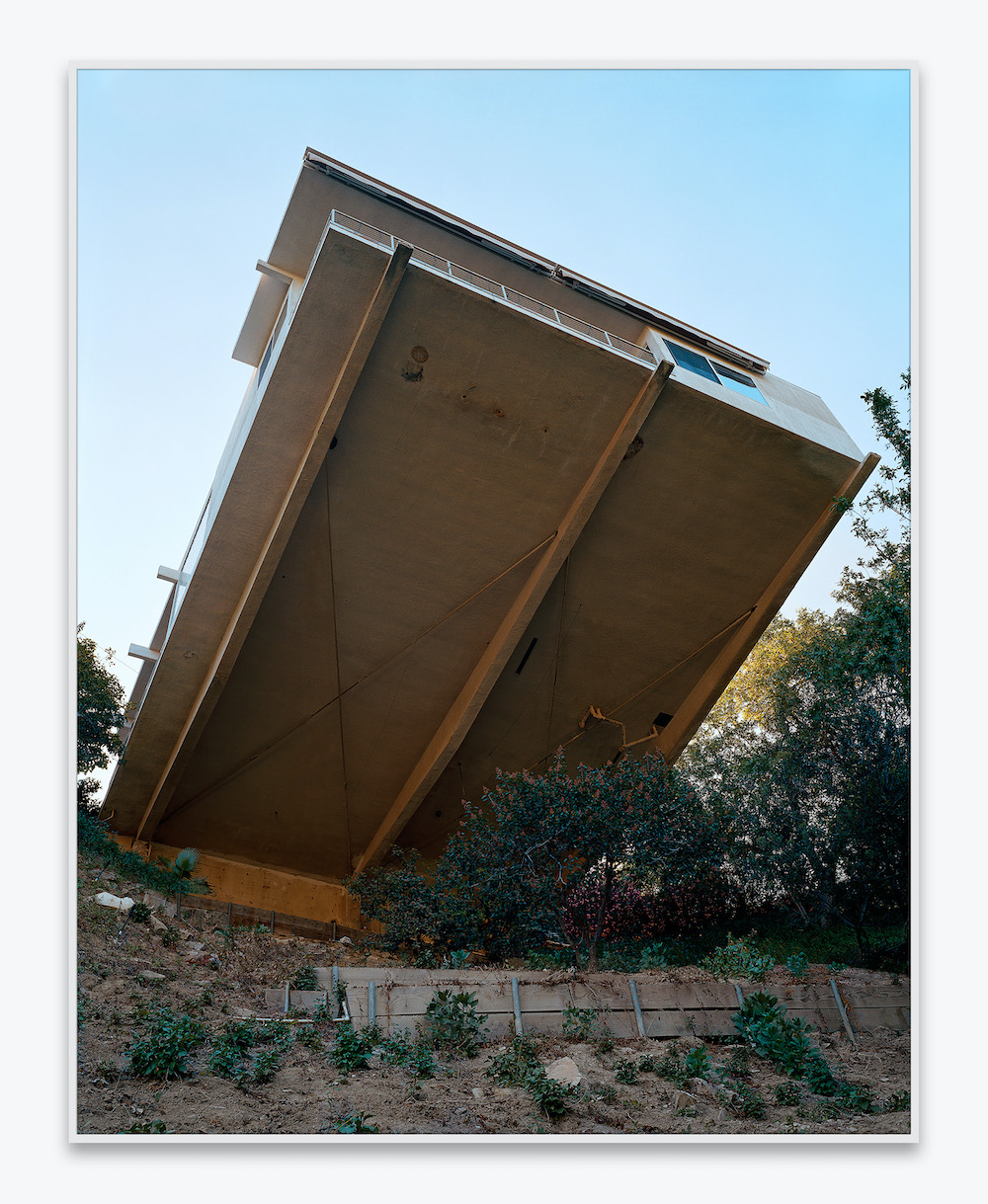

In responding to Zaki’s work, I find myself oscillating between the sensuousness of his photographs and my own desire for art to be revolutionary—that is, for art to engage in conversations that challenge and alter individuals, society and politics, for art to be at the core of vigorous debate. I see in Zaki’s work—in several of his series—a measured coolness, which combined with his explicit editing, complicates the images beyond mere manifestations of desire, as Zaki claims for them in conversation with Peipon. Think of the imposing bellies of houses (Untitled (OH_19X), 2004) perched on hillsides without support columns in his “Spring Through Winter” series, or the crumbling or close to it beachside cliffs with what appear to be private beach-access staircases (Coastline Cliffside 16, 2012, or Coastline Cliffside 22, 2012) in “Time Moves Still.” These photographs produce a kind of estrangement from the familiar and propose a darker, grittier reality that lies beyond the idyllic vision. Even while evoking Weston’s neoclassicism (“Time Moves Still,” “Formal Matter” and other series), Zaki’s photographs form a kind of speculative work. Further, they suggest a deconstruction of the attainability of success, as a state that is either just out of reach or threatening to come crashing down. As theorist and critic Fredric Jameson notes in Archaeologies of the Future, speculative vernacular creates space for a nuanced critique of social conventions, structures and politics.

Ashton and Michaels discuss Zaki’s use of technology at length. Other artists creating photographic works with technology and information systems have done so more directly to activate critique or commentary. For example, Jenny O’Dell’s “Satellite Collections” and “Satellite Landscapes” shift the point of view to planetary systems. Doug Rickard’s “A New American Picture” series, taken from Google Street View, relies on the ubiquity of Google to comment on racial inequity and privacy issues.

Arguably, all three, diverse as they are, find common lineage in Bernd and Hilla Becher’s work and in photography’s use as a conceptual strategy, as seen in Ed Ruscha’s Some Los Angeles Apartments and other series. That extends to the New Topographics artists, whom Zaki counts in his lineage (specifically the Bechers, Joe Deal and Lewis Baltz), and who also moved photography beyond the singular image and mythologizing of Weston’s neoclassicism, into the realm of documentary, taxonomies and social critique. But the contemporary moment is full of images and objects that occupy both sensuous and revolutionary spaces, simultaneously

-

The Zen of Skate Parks and Broken Vessels

A Conversation with Amir Zaki, Part 2CM: The other part of this exhibition (Empty Vessel – Amir Zaki, at the Frank M. Doyle Arts Pavilion, Orange Coast College) are photographs of ceramic vessels. Are they in fact broken?

AZ: You brought up the last body of work at ACME, which is important because that work provides context. In addition to the rocks, there were wooden sculptural pieces. Those were completely 3D constructed. The forms were made with an algorithm and a random process, almost as if you dropped a handkerchief in the sky and froze it in a formation. I then photographed wood veneers and applied that texture to create the forms. They were incredibly artificial and complicated.This body of work started the same way. I had been photographing skate parks. In the middle of it, I started to think of the skate parks literally as carvings in the earth, into which they pour cement. It becomes a complicated vessel. With my interest in Eastern philosophy, I began thinking about the symbolism of the empty vessel as a container for potential energy or potential action. All these things were ruminating, and I was interested in ceramics. But what I really wanted to do was deal with the breaking of the vessel, the dysfunction. This goes back to taking a functional object, like a bowl, and making it dysfunctional. So I started making them digitally. I looked at software and algorithms to break them with random processes. But something about them looked fake, although I didn’t know what.

Broken Vessel 115, 2019 So I just bought something and broke it. I had been taking videos with my phone and posting them on Instagram, breaking things just to study them. Then I thought I didn’t need to work digitally, that this could be analog. So I started gluing them back together — breaking and gluing and photographing. Through this process, which was about five or six months, I had broken one and had extra shards lying around in my studio. While I was figuring out how to photograph them, I realized the shards were all I needed. And so I put one down and photographed it, and I thought, “Everything I need to talk about in this work is located in a broken piece.” It implies — in the way that you were talking about how the skate parks imply the social — this fragment implies the whole.

So then it was a matter of finding a way to photograph them that didn’t look like a studio. I constructed a space in my backyard, which during the late afternoon has sun coming through palm trees. I made a rule that it had to be windy so that there would be a kind of quality that’s constantly changing. They’re basically being photographed under natural light that is filtered through — here’s the California part — palm trees. So I didn’t have full control over the light or how they look.

Broken Vessel 34, 2019 That’s how the project evolved. It’s a long way of saying they ended up being, of the work I’ve made in the last 20 years, the straightest photographs I’ve made. But they’re always seen in the context of people wondering. For me, that’s great. I’ve built a reputation of making people being suspicious — they walk in feeling suspicious. I’m happy to share the process. I’m not coy about it, but I do like that the veracity of photography is tumbling. People say, well that’s veneer, or that’s probably fake. Or he probably did that on Photoshop.

That’s how the ceramics became part of it. When I was putting them in the studio, it became natural for me to think about it as not being based in language but on how your body reacts to the fragility of a broken pottery shard versus the kind of permanence of these concrete forms and the cracks relating to each other.

Broken Vessel 92, 2019 There’s also a connection in that we refer to our bodies as vessels, so it poses metaphoric relationships to you as the viewer observing the broken vessel and the vessels you’re referring to as skate parks, as well. How do you think about the empty vessel in light of your interest in Eastern Philosophy?

I had to write a small piece for the book, and I ended with part of a chapter from the Tao te Ching, which is the most famous piece of Taoist literature. It is about the empty vessel, and to paraphrase, it says, we shape clay into bowls or into vessels, but it’s the emptiness that makes them useful. We build homes, but we cut out windows and doors, and it’s those cutouts that make them useful. It’s this poetic repetition. It refers to this idea that, first, you need both. When most people think of empty, they think that means that it’s nothing. Or they think that it loses its usefulness. But in fact, that emptiness is what makes it useful.I see these as potential. The skate parks are potential for activity — skaters using them the way they were designed to be used. Certainly a bowl has that kind of potential. The thing about the broken ones is that I’m doing something a little bit more transgressive, where I’m prioritizing the photograph over the object. There is such a resurgence of ceramics, now, and this project allows me to be in dialogue with that. People experience much of that through images, which are basically studio images of ceramic objects floating in space. They’re certainly not functional. So I was thinking, there’s really no difference between them and thrift store-items that I just break and photograph in a really evocative way.

Broken Vessel 112, 2019 As a synthesis of the project, I started making limited edition boxes. Each box contains a poster, a concrete bowl, a print, and a poem. You discover the poem at the bottom of the box, only after you’ve pulled everything out. It was written by one of the very first female Zen masters, from the 1200s. It is an enlightenment poem, which describes the moment of her enlightenment: “This way and that way, I tried to keep the pail together, hoping the weak bamboo would never break. Suddenly the bottom fell out, no more water, no more moon in the water, emptiness in my hand.” For me, the poem relates to all this.

I made the 49 bowls in the dumbest way you can possibly imagine. I had a rock about the size of a head, and I made concrete balls, which I smashed onto the rock. The concrete sat like that, dried, and then I pulled it off and used that as a mold to make all 49 of the bowls.

Although they are all made from the same mold, they’re very different. I made no attempt to make one more beautiful than another or one better than another. It was about the idea of not discriminating.

All the titles come from a Zen poem, an important text that I’m interested in. I pulled words that are evocative and used those as titles. There’s no real relationship. I didn’t look at this one and say, you should be called independent. It was simply one after the other. The poster has images of each side of all 49 bowls. So it’s top and bottom. The idea is that anybody who wanted one of these would choose. They wouldn’t just get number 2 of the edition. They could choose based on some aesthetic, or because they really like the word sensation and the way that bowl looks. And so the one you get is circled and initialed by me on the poster. It’s kind of an artist’s book.

The print is literally a synthesis. It is a broken vessel and a skate park that are sitting within one another.

These are fragile. Some of them will probably break. The box is made of cardboard. It’s not archival or meant to be permanent. And so there are these ideas about impermanence and not discriminating between one thing or another, which are these Eastern ideas that I’m playing with. This is a little new for me, but this is a great opportunity in this context to show it.

Broken Vessel 104, 2019 The title of the show is Empty Vessel, which you said speaks to the idea of potential. All of the photographs of the ceramics, they’re all in various stages of being broken. What is the reason for that?

I think what is latent in that, especially if you know the background of how they came to be, is that it brings up an ethics. So for instance, when I would buy these, I would go to Goodwill and look through racks and racks and choose ones that thought would make good broken pieces. I’d collect them in a basket, and the person at the checkout would ask, oh, do you want me to put these in paper for you? And I would say, no, don’t bother. And then there would be a conversation about how I was going to break them anyway. I was posting this process on Instagram, and I found it interesting how I tapped into people’s discomfort with the idea of destruction — that I’m intentionally destroying something that is perfectly functional. I think I knew that going into it. And I think that it fits with an ethos I have about all of my work, which has to do with questioning that value system. To me, I rescued things that were destined to sit in the Goodwill forever. They were already someone’s trash. And in this process, again, the ideas of destruction and creation — this is the Eastern part of it — those are not different. It’s Yin and Yang. So if you’re working with destruction, you’re working with creation too. So what I ended up making was a photograph of an object.The aesthetic purpose of the thing just shifted from one thing to another. And the functional purpose shifted too. Now it’s an object of observation, not something you put water into. But it’s not destroyed.

And the values that are imbued with it have shifted too. But it was interesting because there was a clear delineation. People thought of it as a destructive act, violent too. I would show videos of it slow motion, things breaking, which was really fun for me. There’s a thought that there’s a kind of violence in that. I’m less interested in that because it doesn’t really fit with what I’m doing, but it is intended to maybe feel slightly uncomfortable.

And I like the idea of seeing that absence. That what we do when we see these is to imagine what they would be whole. We fill in the space. And I think that there’s a relationship to the skate parks, where people fill in these spaces with people or skateboarders. You look at a particular shape and you think what they might do in it. And I see those things as being in dialog with each other.

All images courtesy of the artist

-

The Zen of Skate Parks and Broken Vessels

A Conversation with Amir Zaki, Part 1This interview with Amir Zaki was conducted on September 16, 2019, in advance of his exhibition “Empty Vessel” at Orange Coast College’s Frank M. Doyle Arts Pavilion from Sept. 19–Dec. 5, 2019.

Christopher Michno: “Formal Matter,” the last body of work your exhibited at ACME (2017), referenced Modernist landscape photography in the West, and in California, especially Edward Weston. It also engaged with the discourse about photography’s truth claims — which has been an ongoing theme in your work from the beginning. Starting with the mid-century modern homes, which are very improbably perched on precipitous hillsides (“Spring Through Winter”), through to this new series on skate parks (“Empty Vessel”), you appear to address iconic images of California, but in a subversive way.

Do you see the work as a way to undermine or problematize notions of the California dream?Amir Zaki: Maybe. The dream part is an interesting one. The photographs I make are essentially manifestations of my desires. It took me a while to figure that out, but basically that’s how I view what I’m doing digitally: I’m manifesting images of California, or wherever I am, which are about my desire — which means that if I happen upon this place that fits within this desire, I photograph it.

If I need to alter the image in post-production to make that better, I’ll do that. That’s how I view the idea of truth or the veracity of photography.

As far as the dreams, I don’t know what someone else’s notion of California is, so in that way, maybe I’m undermining someone else’s idea of California.In regard to manifesting your desires, I’m interested in the gap between the reality and an idealized or “pure” experience. What motivates you to digitally alter your images?

So much of photography is about observation. I’m cultivating and fine-tuning that observational skill, which is often about finding interesting things that would be otherwise overlooked. And it’s not just the subject of the landscape but where my body is within the landscape.For example, with the Neutra homes, those photographs were about being underneath those structures. That’s not the point of view you’d normally see that photograph taken from. So these photographs emphasize the location of the subject, which is the viewer. The viewer becomes my set of eyes, and you now are in the position I was in.Within these skate parks, a lot of what is both alienating, and I would hope, engaging about them is that the photographs are taken from positions that you’re in only when you’re inside of them. These are not from the perspective of the observer — the parents outside the fence looking in. That is a through-line in my work: where I am as the subject.

There are also never people in my photographs, and that allows you to become the subject. Any photograph with a person in it, immediately that person becomes the subject. But in my pictures, the viewer as the subject is a surrogate for me as the subject.

Amir Zaki, Concrete Vessel 130, 2019. Courtesy of the artist. The scale of your photographs is immersive. There’s also a perceptual aspect that relates to how your digital alterations shape the viewer’s perception of the space, which seems related to how we experience and remember places. Our observation is bounded by time and position and our own perception and recollection. So when we return to a place, it’s not exactly the way we remember it.

Is that something you’re thinking about when you’re photographing, or is that just a by-product of the work?

It’s really important. This project actually started and hit a dead end four years ago when I was skating — again — in my middle age. I realized then how incredible skate parks are, architecturally and formally, but I couldn’t figure out how to make it work with all the people and fences. It dawned on me a couple of years later that I should show up early in the morning, which is when I want to photograph anyway.I never know what I’m going to do in post-production, especially when I start a project. That comes through play. I go through lots of variations. For nine months, all this work was in black and white. At some point I decided to do it in color, and I became interested in the subtle variations of concrete.

You mentioned the body of work of the rocks on the beach (“Formal Matter”). I noticed that in the last 10 years, in post-production as I was zooming in and looking carefully at my photographs, there would be a random bird somewhere, which I definitely didn’t notice when I photographed it. One of those beach scenes has a hummingbird in it, and it’s so out of place. It just happened to be captured by the the gigapan system I’m using. I don’t know how much you know about it, but these are all stitched together from multiple images. Let’s just say this scene is made of 40 to 60 photographs. It zooms in. You’re using a telephoto lens, and you’re registering the top left and bottom right, and that’s all the machine needs. It photographs rows and columns of images. Each image might take five or even ten minutes; it depends on how meticulous I am and on a lot of other things.

The light changes and other things can happen. For instance, birds come in and out of flight. It could have been coincidence, but I started noticing early on in this project that sea gulls and crows gravitate to skate parks.

I thought of sea gulls and crows as the most banal of birds. For entertainment purposes, I started photographing them separately. Then I decided that every photograph of the sky would have a bird, so I’d either have one in the photograph naturally or put them in during post-production. I don’t distinguish between the two.

So that’s where you depart from the veracity of the image?

Absolutely. And some of the modernist ideals that I’m also really indebted to. Weston is a hero, but that would be sacrilege. But that seems to be the most truthful position to take at this moment and in relation to when I learned photography as it transitioned from analog to digital. It makes the most sense to me to use all these tools at hand. And I’ve always been suspicious of celebrating a photographer’s good luck. The idea that someone happened to be in the right place at the right time to capture something is put on the pedestal. But I can make a photograph that manufactures that and the resulting image is identical. The difference is an ethics that’s built into celebrating that moment of good fortune.

Amir Zaki, Concrete Vessel 71, 2019. Courtesy of the artist. There’s a kind of Platonic purity and sublimity to the images you make, yet you’re introducing these distortions.

I’ve always thought skate parks are incredibly seductive — in their geometry and austerity. Your pictures of rocks isolated on those beaches and the iconic houses — these also reflect an austere formality. Where do you think that comes from?

Probably my love for photography is built on images that I love and find really arresting. I teach photography and show my students the canon of all these photographers. I still get really excited about all sorts of photographers — surprisingly some of them doing very different work than what I do. There are portrait photographers who I think are really incredible, and that’s something I could never do. And certainly there is a long history of the built landscape and the natural landscape.Beauty is a tricky word, but I’m unapologetically interested in making beautiful things. I think that at the same time, there is usually an element of alienation or foreboding quality in the work, or at the very least, something that makes you ask, ‘What is this?’

The work you’re talking about, with the Neutra homes, I had architects say, wow, that’s crazy that it stands like that. I had done all this digital stuff, and I’d say, well, no, it didn’t, and I did this to it. And then with the lifeguard towers, there were people who didn’t know they were lifeguard towers. So with almost every body of work, there’s an element of surprise for me. What I’m doing is making these things less familiar. Where I stand, and how I’m photographing it, isolates and decontextualizes it.

I have talked to a lot of people who feel the way I do about the work, but I showed this work to a curator early on, and they had a drastically different response to the concrete. It reminded her of concentration camps. That was important for me because it was a negative reaction to the look of these forms. So I’m totally optimistic about these. It goes back to my desire. I’m trying to make images that I can stand behind and that I think are beautiful, engaging and slightly strange, but certainly not negative.

This gets at what I brought up earlier about deconstructing the California dream. You’re talking about decontextualizing these settings and these objects, making them strange. Part of that has to do with defying easy recognition. Another part of it is that the alienation you’re talking about has to do with taking these very iconic subjects that have defined particular cultural moments. For example, the Neutra homes, those represent what is regarded now as elegant design, but they grew out of a particular European architectural movement that aspired to bring low-cost socialist housing to Southern California, and it failed.

Skating as we know it emerged from the experience of the so-called Z-Boys, who developed a guerilla-style of skating. They overturned the staid skate competitions of the 1970s and skated empty swimming pools. Skaters create their own community in skate parks, and some of them live marginalized lives. I’m reading into what you’re creating as taking something very iconic and pointing to an alienation that sits underneath that idyllic notion. But there is an extensive social history that informs these and can be inferred.

I think that’s a good way of putting it. When I think about the work or write about the work, I often return to ideas about function and dysfunction. The Neutra homes, yes, and especially what I did to them: removing any visible support that they could have and photographing them from their underbelly was really about highlighting the dysfunction, but in a monumental way. I still want them to be heroic, but the way I’m looking at them highlights a dysfunction.The skate park photographs are similar. Without skaters in them, I was photographing things that are a little more subtle. For example, photographing after it rains so there are puddles, or with leaf piles in the images—those are important aspects. That highlights dysfunction. Those conditions are a bad if you want to skate. For me, of course, it becomes something important. The signage that would be the park rules—I’ve done this for years—when there’s a sign in the photograph I turn it into monochrome. I don’t know if what you are getting at is that I’m looking at them in an ahistorical way, but I’m not foregrounding the social part of the work. I’m also not ignoring it. I’m thinking about it, clearly. You can’t erase it, for one. I didn’t make the pile of leaves like that; it’s just a byproduct of that space. So I hope that people think about the social, but it’s approached from the perspective that I’m making visual art. I’m interested in the process of working from the bodily to language. If I wanted to be language-based or talk about the social context based in language, I’d write. But I’m not a writer.

That’s the way I would approach that subject if that were the most important thing, to talk about the social history of skate parks, or Neutra, or housing. I’d probably approach it in a different medium altogether. I feel that the strength of a visual medium is how it affects parts of your being that are pre-language.

It’s also an open signifier.

And this work particularly — this was definitely an accident — but the pop-culture quality of this particular subject matter is something I haven’t explored before. The Neutra homes and the rocks are more esoteric. This series came from the same reasoning, the same desire to look at some part of the landscape that I feel hasn’t been explored in the way that I’m interested in exploring it. But skating is so—it’s going to headline the 2020 Olympics. It clearly has become a huge pop-culture reference.

Amir Zaki, Concrete Vessel 31, 2019. Courtesy of the artist. Back to iconography, I read that these are all very recognizable parks?

There are hardly any that aren’t recognizable. Anybody who’s a local will recognize them. I showed these photographs in Seattle, and there happened to be a kid there who was really into traditional skateboard photography. He knew all of these parks. He looked at one and said, ‘I’ve been to that park. Did you do something to that?’ He could tell I had distorted some of the landscape.Are the parks all in California?

Yes. I have fantasies about expanding this project to other places. There have been a couple that I was just too scared to photograph. People get really local about them. There’s one in San Diego that’s in a really sketchy industrial place, with a chain link fence. Others I was just able to get in.I didn’t photograph Venice, but I would like to. I think that will be very difficult. I could probably swing it in February at 6 am, maybe. I usually have about 2 hours, where a few people show up, and I’ll ask for a little time before they start skating. They’re usually really cool about it.

To be continued… Check in next week for Part 2 of this conversation.

-

Sean Raspet

Various Small Fires-LASean Raspet’s debut at VSF-LA is both an invitation to critically examine anthropogenic climate change—and how we are all implicated—and a series of proposed bio- and geo-engineering solutions for ameliorating the effects of the escalating climate crisis.

Raspet’s practice is as much a record of the workings of technological systems and their linked legal and financial instruments—and as such, a cataloguing of late Anthropocene systems—as it is a making visible how petroleum dominates contemporary life. An accounting of past projects yields works on synthetic flavors that infuse food products, chemical signatures of consumer goods, and a gallery slathered with a transparent synthetic DNA gel normally used in corporate anti-theft schemas. In pulling back the curtain, Raspet points to the proliferation of synthetic (petroleum-based) molecular compounds, and how they are consumed, thus becoming substances we “metabolize.”

A visually lush installation of more than 50 genetically modified plants (∂ (various species), 2019 and ongoing) emerging from planter boxes outside and small wall-mounted containers inside, appears not as scientific display or archival catalogue, but as if each plant were a small jewel. Yet these experimental subjects have been irradiated or exposed to chemical mutagens in an effort to accelerate the occurrence of genetic mutations—the goal being to increase adaptability to a rapidly warming environment.

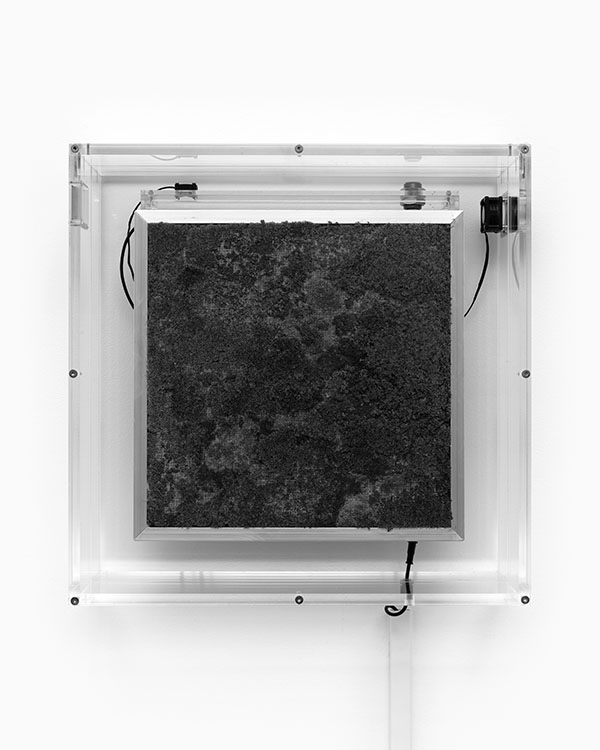

Sean Raspet, Exhibition View, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Various Small Fires, Los Angeles/Seoul. Photo by Marten Elder. Another plant-based work gestures to natural processes supplanted by synthetic ones—and conversely, the possibility for biological processes to re-emerge. A patch of moss in a Plexiglas box with small apertures (Filter (Physcomitrium patens: patchoulol synthase-(+), linalool synthase-(+)), 2015–21) is described as a self-fabricating biological air-filtration system—a reference to the exchange of carbon dioxide for oxygen. In a nod to human/plant co-evolution, the moss is genetically engineered to emit the scent of patchouli, which the artist describes as reminiscent of a forest floor.

The third work (Atmospheric Reformulation (CO2 Direct Air Capture), 2019–21), created in collaboration with Swiss company Climeworks, is ephemeral but consequential: one metric ton of carbon removed from the atmosphere. Originating in Raspet’s “Atmospheric Reformulations” series, which investigated the creation of synthetic atmospheres and reformulating Earth’s atmosphere, it is an exemplar of planetary engineering; the captured carbon will be sequestered in volcanic rock.

Each of these works resides squarely within the realm of the anthropogenic, reflecting the contradictions of the Anthropocene; while they reveal optimism on the part of the artist, how they land is a more nuanced affair.

Whether humans are capable of doing enough to ameliorate the worst of climate change—and whether those efforts won’t be fraught with deeply problematic ethical considerations—is a trickier question. Humans’ ethical obligations to the millions of other species, plant and animal, that reside on the planet with us, and the ethical obligations of the global north, which produces the majority of carbon emissions, are quite clear. Yet will our efforts, whether in the realm of bioengineering or planetary-engineering—if we can muster the will and determination to actually make change—initiate a cascade of unforeseen consequences that are just as troubling as the issues at hand?

-

Art Is Everything By Yxta Maya Murray

DEATH OF A DREAMArt Is Everything

By Yxta Maya Murray

229 pages

TriQuarterly

Yxta Maya Murray—art writer, law professor, fiction author—draws upon the disparate threads of her writing practice to construct her new novel, Art Is Everything, a kind of Bildungsroman of the Los Angeles art world.

Written as a series of first-person confessions and guerrilla essays penned by the novel’s sole narrator, queer Chicanx performance artist Amanda Ruiz, the tale is pieced together in a series of snapshots as Ruiz’ art career rises and falls, along with her personal relationships. The novel kicks off with an article of indictment titled, “Hey MOCA, why is Laura Aguilar’s Untitled Landscape (1996) ‘Unavailable’ on Your Website?”

Interspersed with Ruiz’ essay on Aguilar’s invisibility come declarations of love and desire for her girlfriend X–ochitl Hernández, who she describes in ways that intersect with Aguilar—“large-bodied, queer, and of a complex racial background.” Exposing the kind of erasure she also encounters as a queer Chicanx artist and shares with Aguilar, she writes,“… museums either do not collect her, or they conceal her as if they are ashamed.”

The authur, photo by Andrew Brown. Ruiz audaciously places her essays as disruptive acts, hacking museum websites with unauthorized texts, subverting Wikipedia with position pieces, and leveraging social media. One guerrilla post, on the Whitney Museum website, skewers the Max Mara Whitney bag as an unattainable object and unmasks the commercialism of the art world’s high temples. Ruiz’ many compelling texts—on, for example, Sanja Ivakovi´c’s performance implicating the state surveillance apparatus of Yugoslav strongman president, Marshal Tito (Triangle, 1979); Mickalene Thomas’ Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires (2010) and Stendhal; or David Wojnarowicz’ death portrait of Peter Hujar—are clearly informed by Murray’s art- and law-writing. Indeed, some have their origins in articles published previously, as noted in her acknowledgments. Yet they are wholly believable as Ruiz’ work, composed here in her voice.

In spite of Ruiz’ convincingness as a writer—with a punk-rock ethos—she seems miserable as an artist. Ain’t Nobody Leaving, the performance film that wins her a coveted Slamdance award, ironically documents the dissolution of her relationship with the long-suffering Xochitl, as well as a performance in the extreme—seven days of self-starvation and semi-hallucination. Yet the film feels juvenile and the dialogue utterly pedestrian: “I’m really hungry and I can’t believe that you are eating that sandwich in front of me,” and “What does love even mean?” Her other projects feel one-dimensional as well.

In an early essay on Agnes Martin and Jean Genet, Ruiz asks how artists survive a break—foreshadowing the impending attenuation of Ruiz’ art production, which withers away post-X–ochitl. In a particularly exquisite chapter titled “Private Language”—on Wittgenstein, Melville and Hawthorne, the semiotics of love, and the limitations of our subjectivity—Ruiz writes on what it feels like to be destroyed by love. The final third of the novel answers these two concerns in a variety of ways, each acknowledging the difficulty of making a life after loss and the death of one’s dreams. It is no surprise that Ruiz turns to art writing when her performance work is exhausted, for that is what she has been all along—a writer—which we readily recognize from the handiwork of Ruiz’ dexterous creator.

-

Kader Attia

Regen ProjectsKader Attia’s debut with Regen Projects —a selection of previously exhibited and new works—continues the French-Algerian artist’s critique of modernity as embodied by Western capitalism and the mechanisms and ideologies of colonialism.

Attia has frequently examined the particularities of French-Algerian colonial history, while implicating global colonial structures writ large. “The Valley of Dreams” takes its point of departure from these conceptual grounds, with a series of three works installed in close proximity, in what is the most coherently developed portion of the show.Rochers Carrés (2007/2020), presented here as a lightbox, depicts two Algerian youths looking north across the Mediterranean from an Algerian breakwater. This is juxtaposed with the variously sized refrigerators of Untitled Skyline (2007), covered in a mosaic of mirrored tiles, evoking the image of a gleaming modern city. Like the glittering nocturnal skyline of New York City, it reflects the dreams projected upon it.The Dead Sea (2016), an installation of clothing that spreads from a corner of the gallery, conveys the perils of crossing the Mediterranean in search of refuge and opportunity. Together, these three implicate the dream of migration, wherein the sea becomes a graveyard, and the remaining traces—the very clothing off migrants’ backs—collect on the shores of Europe.

Kader Attia, The Dead Sea (detail), 2015. Courtesy Regen Projects. Attia asserts, without much elaboration through the objects presented here, an “analogy between California, New Mexico, Texas, and North Africa,” suggesting similarities of climate and patterns of migration and its attendant dangers, from which we may draw inferences regarding the cross-border disparities and analogies between sites of colonial and neocolonial relations.

The remaining works in “The Valley of Dreams” (all dated 2020) reprise various aspects of Attia’s critique of colonialism and interest in the notion of repair. A series of Berber ceramic vessels, once shattered, now repaired with a brilliant blue epoxy—the color selected for its association with the Tuareg people—emphasizes Attia’s interest in the Japanese tradition of kintsugi—the repair of pottery while preserving the visible scar. This same blue pigment appears along the folds of kraft paper—discarded powdered milk packages delivered to North Africa by NGOs—that has been crumpled and spread out to resemble what might be a topographical map.

Yet, Attia does not adequately address the context of Southern California or the neocolonial structures of the US The strength of postcolonial analysis derives from elaboration of the particularities of site, which Attia has done elsewhere—and here, in relation to North Africa and Europe. Though parallels from varied examples may be drawn—and the similarities between migration to Europe and the US are well observed—the lack of research on the specifics of this site makes this exhibition feel like an import.

-

Mildred Howard

Parrasch HeijnenThe profoundly moving installation Ten Little Children Standing in a Line (One Got Shot, and Then There Were Nine) (1991), positioned to be the first work encountered in Parrasch Heijnen’s career-spanning survey of Mildred Howard, imparts a sense of the Oakland-based artist’s interest in framing social and racial inequities through a personal lens. Hundreds of 9mm bullet casings are affixed to the wall in a grid pattern. On the adjoining wall, a banner with an enlarged news photo and AP Wire clip from the 1976 Soweto Uprising contextualizes this display of lethal power. The image captures one moment in the aftermath of the South African police’s brutal response to students protesting Apartheid policies. One student bears away a lifeless boy—a protester murdered by police gunfire.

The enduring relevance of Ten Little Children derives from how it speaks not only to the ongoing reality of racial inequity but also to the dynamics of power and political and social change—and for the artist, it operates equally on an intimate scale. Her comment, delivered in a lecture at another venue—that any of the murdered students could have been one of her own—illuminates the empathy evident throughout her practice.

The exhibition comprises selected works from more than four decades and reflects Howard’s experimentation across diverse media, ranging from color Xerox photomontage to sculpture and installation. The most successful of these are crisply realized installations that deftly merge message and material.

Mildred Howard, Parenthetically Speaking…It’s Only a Figure of Speech, 2010. Courtesy Parrasch Heijnen. Another such example, the blown glass installation Parenthetically Speaking: It’s Only a Figure of Speech (2010) follows Ten Little Children by nearly 20 years. Created during a residency at the Pilchuck Glass School, the beguilingly sensuous, yet imposing series of punctuation marks is a collection of braces, semicolons, ellipses and the like that are nearly abstract in their elegance and sophistication. Absent of narrative, Parenthetically Speaking presents only the structures that shape thought and language. Howard describes the interstices as the spaces where individuals will write their own stories, thus inviting her audience to insert themselves into the work.

Similarly addressing questions of representation and voice, Volume I & II: The History of the United States with a few Parts Missing (2007) insists that we infer which parts are missing. Side-by-side atop a pedestal, the two volumes sit open. Holes have been drilled through the pages, leaving gaping absences in the texts. The visible sections on the Louisiana Purchase and immigration policy in the early 1900s, respectively, read like typical history textbooks—glaringly eliding accounts of the slave trade, the plantation economy, genocide, discriminatory immigration policies and ideologies of “unassimilable races.”

In many of Howard’s works, the symbols of empowerment and voice appear, often as mirrors, or more literally, in photo works depicting ordinary people, or even representations of the artist herself. Starting with her own experience and then expanding outward, Howard’s work asks the question of whose histories are deemed important? The response, found throughout her practice, is to center the experiences of those who have been written out or ridden over.

-

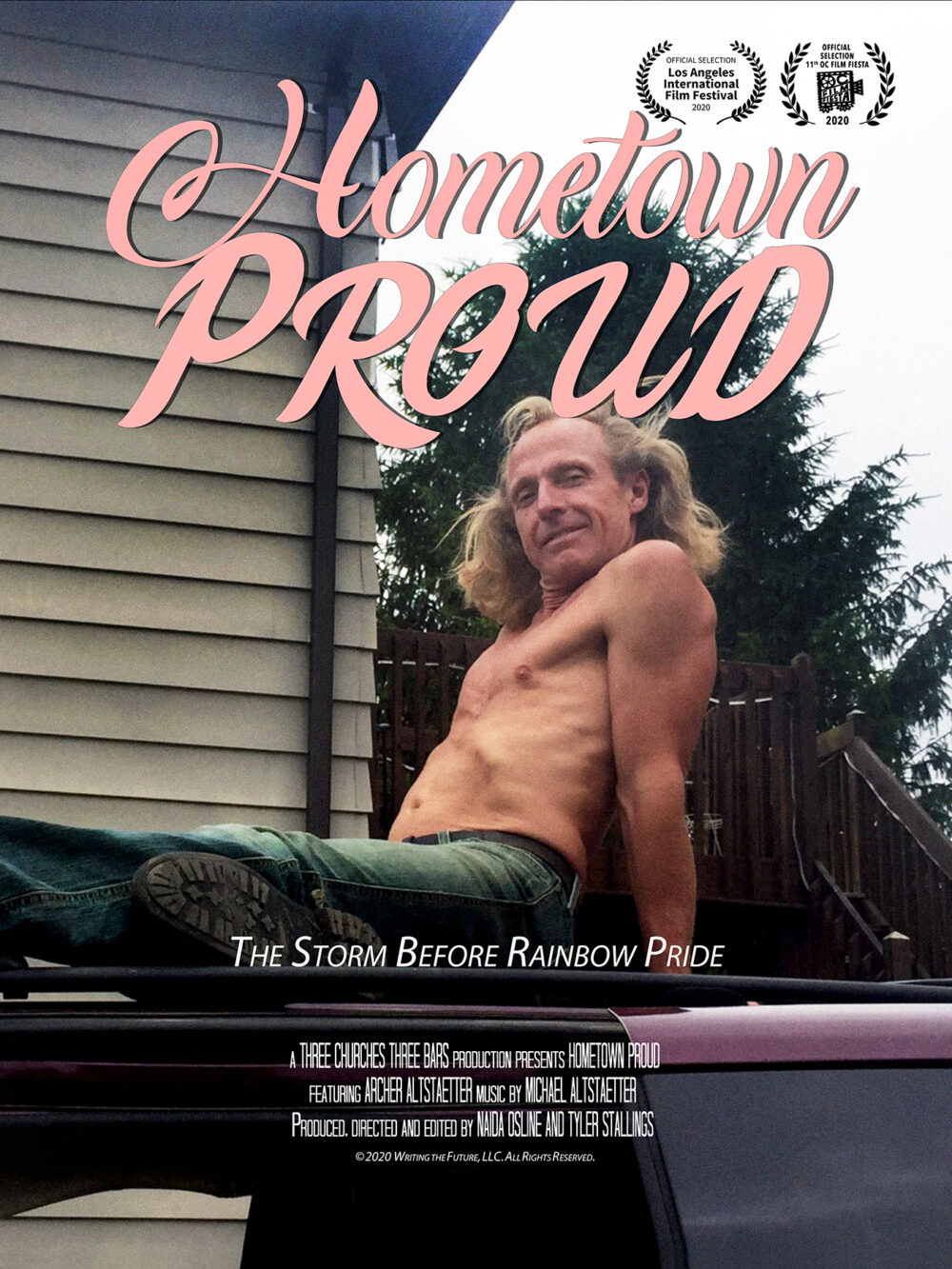

Film: Hometown Proud

Debut Documentary by Tyler Stallings and Naida OslineHometown Proud, the debut documentary by Tyler Stallings and Naida Osline, speaks volumes to our current political and cultural environment. The project grew out of their interest in exploring social issues through their individual practices, for Stallings, as a curator, and Osline, as an artist. Filmed in 2018—a year in which the Trump administration worked assiduously to erode legal protections afforded the LGBTQ community, often in the name of protecting religious freedoms—Hometown Proud follows Archer Altstaetter, an openly gay Southern California man, back to his small, rural hometown of Botkins, Ohio, for a dance performance he has been invited to give in the community’s annual “Miss Carousel” pageant. Altstaetter, who left Botkins to pursue a career in dance, is former dance studio owner. He still designs costumes and produces shows that run the gamut—“Everything from nightclubs with go-go dancers and drag queens, to little kids running around in fluffy tutus.” For the sleepy, yet conservative community of Botkins, the place where he spent his youth—feeling acutely that he didn’t fit in—Altstaetter choreographs his dance number as an expression of Rainbow Pride.

Archer and his mom, Ruth, atop his homemade Gay Pride float that he snuck into the parade. His brother, Michael, drove the van. Still from Hometown Proud, 2020, 60 minutes, directed by Naida Osline & Tyler Stallings. The film quickly establishes through observations made by its subjects, cultural rifts that are reflected in communities across the country, large and small, and writ large in everything from our electoral politics and battles over Supreme Court nominations, to small business lawsuits over providing service to LGBTQ people. To its credit, the film never mentions the national stage or the larger issues being contested. Instead, it works to build a sense of import and the risks—of potential violence—LGBTQ people experience in America, through interviews with residents of Botkins. Many of these are with Altstaetter’s close-knit and supportive family: his brother Michael, who speaks fondly of his youngest sibling and composes the musical accompaniment for his choreography in the pageant; two nieces, one who is gay and out, the other an ally; and his mother, whose love for Archer is clear. Other interviews are with the mayor, the pageant chair, the historical society vice president, a retired history teacher, and a young LGBTQ person.

Maddie Wagner, featured in the film, and longtime resident, who made it possible for same-sex dates at future high school events. Still from Hometown Proud, 2020, 60 minutes, directed by Naida Osline & Tyler Stallings. What emerges from these interviews, as the film moves from Altstaetter’s preparation, to the pageant and Altstaetter’s performance, and beyond, is the sense that acceptance in this small town is predicated on conformity, and centered on being straight, Christian and white. For every comment—from those fitting the “norm”—that Botkins is a safe place to live and folks there take care of each other, another, from someone within Altstaetter’s circle, complicates or refutes that picture. The reality emerges that it’s a frightening place to grow up if you’re LGBTQ. Hometown Pride shines in these moments, as it builds a nuanced portrait of what it is like to live in this environment.

There are times when the film wanders, covering more territory than it can resolve or cover in sufficient depth in its short 60 minute run time. There is, for example, the mention of Altstaetter’s father and domestic abuse. Altstaetter calls him a sociopath. After leaving his family, a dispute with a business partner in California ended with his body being found in a shallow grave in Angeles National Forest—a story that easily could be developed into another full-length film. But the filmmakers’ interest in this project centers on Archer, his experience of growing up gay in a conservative community, and the dichotomy between the professed values of care and the reality of anti-LGBTQ sentiment within that community. Ultimately, some of the anecdotes related in the film feel like digressions. It is tempting to think the documentary would have benefitted from additional interviews with people outside Altstaetter’s immediate circle, if only to illuminate the views of a broader cross-section of Botkins. One might imagine that in additional footage, the filmmakers would have uncovered what is only hinted at in a few interviews. Yet whether anyone would speak openly on camera about their own anti-LGBTQ views is dubious. But there is plenty of speaking in code, which is proof enough, reflecting a microcosm of the cultural and political divide that is playing out on a national level.

Los Angeles International Film Festival, Nov. 8-14, beginning this Sunday. Link for $10 tickets to the festival. All are online viewing in light of COVID. https://watch.eventive.org/la/play/5f8fe2f4606b56005be5fe92

Vimeo trailer for HOMETOWN PROUD, https://vimeo.com/452919122

Website for the film, https://hometownproudthemovie.com -

Materia Medica

François Ghebaly“Materia Medica,” the summer group show at François Ghebaly, curated by Kelly Akashi, is more than a call to reconsider the relationship between humans and the natural world. The show pointedly issues a rallying cry of refusal against relentlessly destructive human systems that are connected with histories of colonial exploitation. A short introductory text—a mash-up of science fiction and manifesto—juxtaposes observations of human activity, as seen on an evolutionary scale, with a series of artistic intentions, such as, “To work from one’s own history… To record nature’s subjugation to human needs. To foretell the co-opting of all life in service to structures of power.”

The exhibition title references an early pharmacological text and millennia of botanical and medicinal knowledge—even as it exposes such knowledge as centered in human subjugation of all life. De Materia Medica, a definitive pharmacopeia by the 1st century physician Dioscorides that sought to classify plant, mineral and animal substances according to their medicinal effects, sits in the interval between traditional knowledge of the natural world and the scientific exploitation of nature.

But in the midst of our post-apocalyptic landscape, Materia Medica posits empathy and organic relations with the natural world. A number of works are allegorical—for example, Kay Hofmann’s hand-carved alabaster sculptures, featuring female figures entwined with organic forms. These reflect an idealized oneness with the natural world.

Catalina Ouyang, font III, 2020, courtesy of the artist, Make Room, Los Angeles, and François Ghebaly, photo by Paul Salveson. Several mixed-media works examine histories of colonization. Catalina Ouyang’s wronging wrongs (2019), shown previously in “fish mystery in the shift horizon” at Rubber Factory in New York, is part of her work on the parallels of species extinction and the transmission of knowledge in diaspora. In font III (2020), in which a raw egg sits in a carved soapstone sculpture resembling a head, and is bathed in vinegar each day while its shell dissolves, Ouyang addresses identity and whiteness.

Candice Lin’s Minoritarian Medicine (2020), a homemade apothecary fortified with various tinctures infused with substances like Astragalus, Echinacea, Reishi Mushroom, and Oxymel (for immune support), and hand sanitizer, alludes to both medicinals based in intimate knowledge of plants and passed on through generations, and to our current pandemic. It is one of the show’s ironies that medicine is needed in the pandemic, and that pandemic periodically disrupts humans’ self-appointed hegemony.

The dichotomous relationship between nature and culture is addressed most explicitly in works by Jessie Homer French and Max Hooper Schneider. Pastoral (1992), an oil painting by Homer French, depicts cows grazing in the shadow of nuclear cooling towers, which presumably fuel the electrical lines stretching above the pasture. Pastoral plays off Hooper Schneider’s installation of a flickering “Jesus Saves” neon sign powered by an aquarium of Black Ghost Knifefish (DIALECTRIX: DIVISION APTERONOTUS (JESUS SAVES), 2020). Electrical signals from the Knifefish are transmitted through copper embedded in the tank, thus illuminating “Jesus Saves.”

Akashi’s text concludes in a resolution: “To become one with nature, to bind with it, to emote from within it;” yet it dispassionately observes that proposals “for empathy, for defense, for action” remained unanswered. And so it dispenses with simple solutions and technological saves and leaves us to answer the difficult question of how to become one with nature.

-

Gala Porras-Kim

The urgency of revisiting an archive is found in challenging its presumed objectivity and totalizing vision, thus exposing cracks, biased ideologies, contradictions and gaps to make way for fracturing, reinterpreting, enlarging or otherwise revising our understanding. Gala Porras-Kim, an artist whose trenchant critique of the archive as a system constructed to sustain colonization has been central to her installations—Made in L.A. 2016, the PST: LA/LA exhibition A Universal History of Infamy, and the Whitney Biennial 2019—has undertaken to curate MOCA’s second “Open House,” a series in which Los Angeles-based artists are invited to curate from the museum’s extensive collection of contemporary art.

Even with Porras-Kim’s evident seriousness in curating, with help from MOCA’s Assistant Curator and Manager of Publications Bryan Barcena and Curatorial Assistant Karlyn Olvido, the results are mixed. Whereas her installation in A Universal History of Infamy, which mounted a critique of how knowledge had been constructed from incomplete information of objects in LACMA’s collection, was pointed, “Open House” remains diffuse, and even anticlimactic.

Installation view of Open House: Gala Porras Kim. Walead Beshty’s FedEx® Large Kraft Box … (2009) and Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1969-1970). Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo by Jeff Mclane. Porras-Kim’s curation of “Open House” is an open-ended inquiry into the mutability of MOCA’s collection that coalesces into a loose thesis about the permanent collection’s lack of permanence. The exhibition examines a series of ephemeral works that are transient because of the materials of their construction, alongside ones whose foreclosure is intended. In the first category, a collaged work on paper, Chris Burden’s Peace (1982) makes use of non-archival adhesives and unstable materials such as Polaroids, cigarette wrappers, newspaper and cellophane—focusing attention on objects in the collection that cannot be conserved, because their materials will crumble into dust.

Richard Tuttle’s 44th Wire Piece (1972/2014) falls into the second category. Unlike Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings, Tuttle’s instructions state that he alone may install the piece. One can infer from its accompanying didactic that the museum might be considering approaching Tuttle to request an alteration, allowing for others to install when the artist becomes incapacitated or deceased. One can imagine internal discussions pursuant to avoiding the loss of never being able to exhibit the Tuttle again, after an indeterminate date looming in the foreseeable future, in distinction to the original conceptual parameters of the artwork.

Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1969–70) presents a similar conundrum. Heizer’s original intent to allow the land art piece to recede into the desert as erosion requires that we orientate to a planetary, geologic time-frame and ask ourselves whether any of the monuments humans have constructed will remain after we have gone. As noted in the didactic, he has since changed his mind and communicated his desire to conserve the work. MOCA, perhaps tellingly, states that these kinds of contradictions “can be points of negotiation between institutions and artists.”

Two additional works in “Open House” suggest ways this exhibition might have been pushed toward a more pointed thesis. The first, Walead Beshty’s FedEx® Large Kraft Box … (2009), a shatterproof glass cube and FedEx® shipping box, suggests a new kind of Vanitas object, in which an insider’s view of the international art circuit reveals the self-referential logic and surfeit of the prevailing system of exhibition and consumption of art.

Wolfgang Laib’s pollen field works, represented here by Pollen from Dandelions (1978), offer a reprise to Heizer’s referencing of geologic time and the implicit rebuke therein. Laib’s work involves a radical consideration and empathy for non-human beings; his process of gathering pollen and his deeply held respect for nature propose ways to decenter the human. The effect of understanding Laib’s process is likely to produce an understanding of the expansiveness of his gesture, which condenses the experience of interacting with plants in a ceremonial way, and its link to seasonal cycles and reproduction.

This final direction would fortify Porras-Kim’s “Open House” with a powerful critique of the archive as an index of institutional interests and the hegemony of human systems. Further investigation of MOCA’s thinking on the permanence of the collection would be instructive, especially regarding objects that may be the subject of renewed negotiation, as related to weighing MOCA’s interests and the value of the collection against the conceptual coherence of the works. But most compelling would be to make explicit the way the objects exhibited in “Open House” advance ideas of decentering the human, which would call into question the archive in its entirety.

-

Theaster Gates

“Blessed are the meek…” – Gospel of Matthew, 5:5

Has Theaster Gates truly “upcycled” his entire wardrobe as a spiritual gesture and a means of achieving transcendence? Perhaps he has. But in the most literal sense, Gates has taken the raw material of his sartorial well and turned it into a commodity: a series of elevated objects (ascots, mostly, and a quilt draped across a massive gantry) to be sold inside the white cube.

The verse from the Gospel of Matthew that inspired Gates to divest himself of habiliment deserves another look. Matthew 5:40 (“If someone wants to sue you and take your tunic, let him have your cloak as well.”) appears within a larger passage that has long been co-opted and purged of its radicalism—a once subversive and liberating call to turn the prevailing social and political order on its head.

But Gates’ use of the “Shirt and Cloak” text is subversive and coded. It becomes instructive then to look at the objects, some of which follow the template of “upcycling;” for example, his use of tar—a familiar Gates theme. Three White Lines (2019), a tar-on-canvas tapestry, equates black labor (which, Gates has noted in previous conversations, reflects back to when African American craftsmen were highly skilled builders) with European high culture—fine tapestries, history scene painting, or the achievements of high modernism (cf. Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko). And though we know it was fabricated, it conjures images of a fragment that might literally have been torn from a Chicago rooftop in the historically African American Grand Crossing neighborhood where Gates launched Dorchester Projects, Rebuild Foundation and Stoney Island Arts Bank. (Roofing was his father’s profession, and as the story goes, he inherited his father’s tar kettle on the older Gates’ retirement.) Other works, which use rubber bitumen, similarly refer to roofing technologies and the independence the black working class enjoyed a generation or two ago (Long Run, Left with Guide Line; Long Run, Right with Guide Line; both 2018).

Theaster Gates, Three White Lines, 2019, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles, photo by Joshua White But the seemingly disparate collection responds to the call to resist power structures and dodgy hermeneutics and firmly anchors this body of work within Gates’ larger concerns around the African American experience.

In the smaller gallery, Flag (2017), made from a decommissioned fire hose (another reprised theme), alludes to the Civil Rights struggles of the 1960s. Along with Diagonal Line for Roofing (2019), it is serenaded by Gates’ performance of the vocal score based on the Gospel verse, which sets the emotional tenor of the exhibit. A mournful free-form poetry spills from speakers embedded in Woah Dee Woah (2019), and one can’t help but consider the violence enacted by white supremacy: “When they come, they will come… give them your shirt, your cloak, go that mile… if the man ask me to go one mile down the road… my horse is tired, he don’ want to go… ”

Man Ray on My Mind (2019), like John Edmonds’ Tête de Femme (2018, exhibited in this year’s Whitney Biennial), references the Surrealist’s now notorious photograph Noire et Blanche (1926)—notorious for being implicated in directly promoting an ideology of European superiority. Both Edmonds and Gates turn that ideology on its head.

Gates follows this rebuke with a meditation on black cultural and literary achievement in Lerone’s Headrest on These Streets (2019)—likely in memoriam for Lerone Bennett Jr., a scholar and the editor of JET and later of Ebony. Gates’ Raising Goliath, (exhibited at White Cube, London in 2012), which balanced on pulleys an archive of JET and Ebony magazines with a 1967 Ford fire engine, similarly celebrates this legacy.

Yet it is imperative to view “Shirt and Cloak” against the backdrop of Gates’ engagement in the revitalization of Grand Crossing, wherein the cultivation of a public square and an extended community is wholly contingent on art—as a countervailing force against the leverage of private capital and an instrument to reclaim the neighborhood for those who live there. Two works (Half Circle with Pier, and Circle Form with Pier, both 2019) use building materials recovered from one of Gates’ projects in Grand Crossing, evoking his many forays into creating spaces for culture that generates social capital.

The economic realities of the commercial gallery place this exhibit uncomfortably between contradictory purposes. And while culture does not exist without investment, another way to understand this work is as a coded text that seeks to subvert the commercial gallery in which it sits. Gates’ insistence that his work be seen beyond the performative platform and the finished object, and instead reference process as aesthetic structure, is perhaps one of the most important reasons for his relentless push into the realm of possibility and his social and critical relevance.

-

Brandon Landers

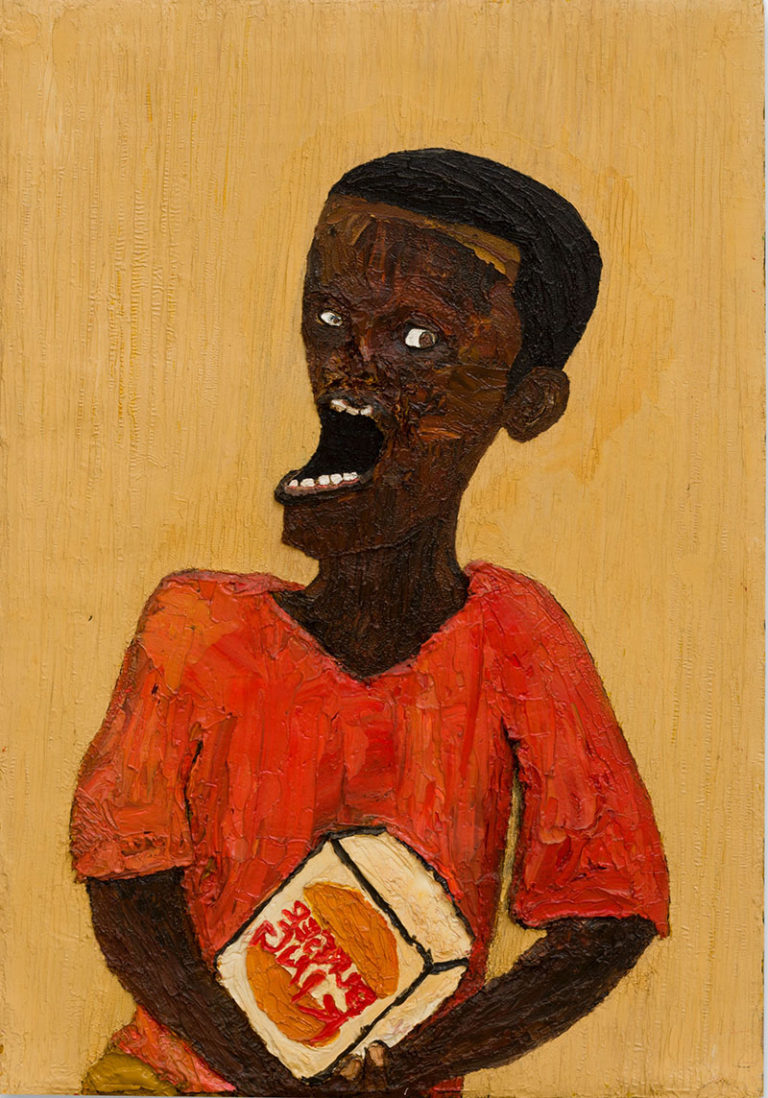

In Brandon Landers’ debut solo exhibition at M+B, the Bakersfield-based, LA-born and raised artist delivers a collection of expressionistic and loosely narrative paintings that draw from his experiences growing up in South Central Los Angeles, yet the works retain an ambiguity that liberates them from a being a direct autobiographical recounting, leaving them open for interpretive possibilities.

Landers works intuitively, strictly with a palette knife, which gives his paintings richly textural surfaces; he frequently scrapes—sometimes to the nub of the canvas—to reveal layers of pigment beneath, resulting in a variegated chromatic effect, in which faces, skin, clothing and grounds take on a complexity that further enlivens them.

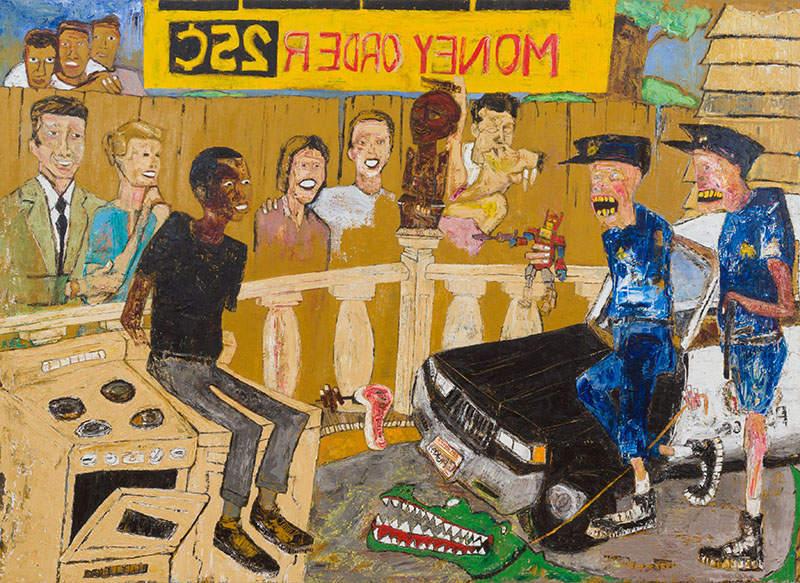

Brandon Landers, Ways, 2018-2019, courtesy M+B His paintings absolutely bristle with energy and exert a remarkable presence, which is perhaps a facet of the vulnerability they signal. Landers constructs scenes with precipitous content and varied and complex relations between figures—both spatial and social. The formal qualities—the impasto, the sensuous, figured surfaces—these effects are compounded by spatial distortions, wherein figuration and facial features convey a certain “wrongness,” giving the impression that things are slightly distorted or out of whack.

Consider these effects alongside his practice of including text or signage, in which words are consistently reversed as if the viewer perceives the scene in a mirror. These add to the representational distancing of the image from its ostensible source material—which has been distanced and refracted through the artist’s memory and imagination. Aside from the metaphorical mirroring, the formal aspect is that signs and other bits of text become graphic elements, adding chromatic and geometric verve. Compare The Joys (all works 2019) to Facin’ the World: the “Money Order” sign atop The Joys contextualizes the scene while it breaks up the figuration.

Though Landers never asserts an intention to create work that reflects the social or political climate, his deeply personal vision yields results that invariably do. In The Joys, a group of spectators looks on as a pair of boys in blue stop to interrogate a young black man. The composition of the onlookers—all white, save an African statuette, which stands as witness—place this narrative in a larger discussion of police violence against African Americans. The cops are ghoulish, their faces represented by a staccato of knife marks in pigment that conjures the reddish hue of tenderized meat. To me, these evoke images as widely disparate as Llyn Foulkes’ bloody head series from the 1970s, Francis Bacon’s terrifying studies after Velazquez’ Portrait of Pope Innocent X, and even figures from James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels.

The pictorial aspects allow for inference about what the scene may mean, both to Landers, and to an observer. The young man’s arms inexplicably trail off and disappear. Are we to take this to mean he is unarmed? A toy transformer, which extends a weapon, is held aloft by three disembodied fingers and points toward the young man. The first cop’s arms, likewise, are not visible. Landers leaves this work and others in this collection, unfinished in places, leaving room for multiple reads.

-

CHIACHIO & GIANNONE

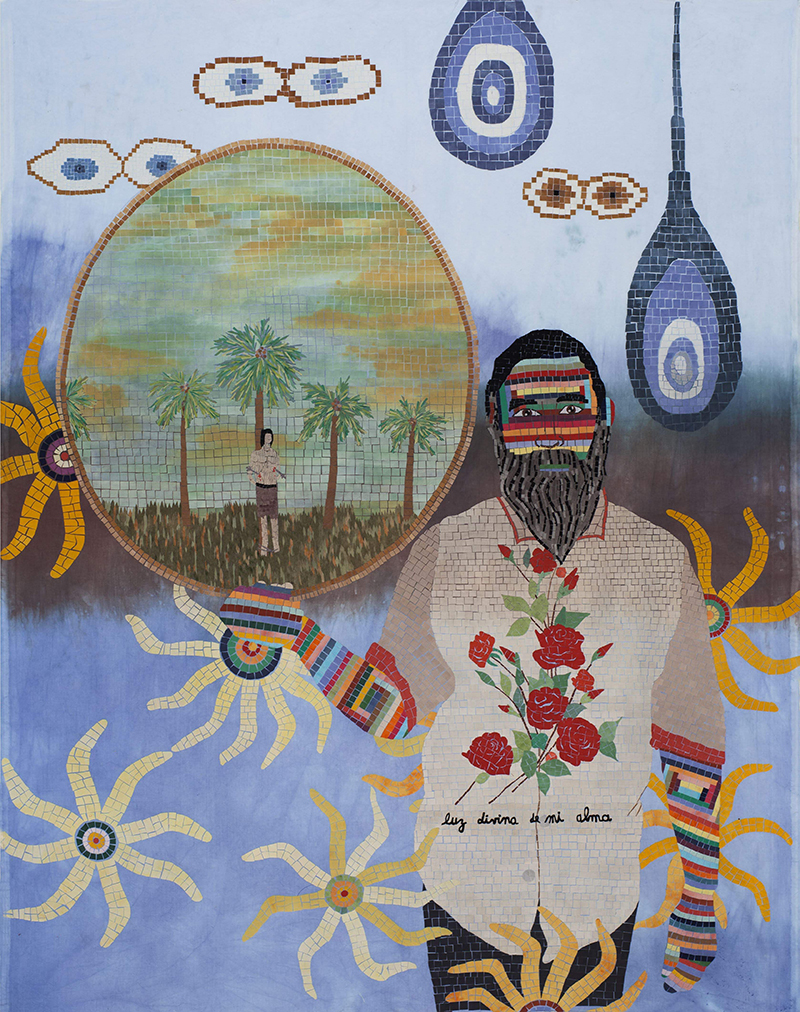

Argentine artists Leo Chiachio and Daniel Giannone who together form the duo Chiachio & Giannone were painters at one point in their careers. Their combined artistic identity has since been forged working in textile, with such labor-intensive techniques as embroidery. The two have created an extensive body of lushly stitched, vibrantly colored hand-made textile works, the focus of which is frequently portraiture—specifically of the artists, who are a couple, and their dachshunds.

“Celebrating Diversity,” their exhibition and residency at the Museum of Latin American Art, is part of an ongoing two-fold project of textile mosaics and pride flags first shown in 2018 at the Kirchner Cultural Centre (CCK) in Buenos Aires, in “Democracy Under Construction,” a group exhibition that examined the future in the context of Argentina’s 35 years of uninterrupted democracy. Their project in that context reflected on the values that underlie democracy: community and diversity, which are at the heart of an open society. In this country, where recent history has shown how quickly those values can be threatened, their work takes on renewed urgency.

Working in craft media traditionally associated with femininity and domesticity, they complicate gender roles and assumptions of “serious work.” In a playful investigation of identity, the duo lightheartedly explores their creative partnership in which the discrete boundaries of the individual blur and shift—like binary stars, the two revolve, in each other’s orbit. Their series of textile mosaics, “Family in 6 Colors,” evoke ancient Roman tile mosaics and redefine and extend the boundaries of family—from the nuclear family unit to the social bonds that are the family of one’s choosing. These ultimately compass their artistic family as the duo devises lineages of LGBTQ positive artists that carry their artistic DNA.

Chiachio & Giannone, Family in six colors #6 / Familia a seis colores #6 (2018) courtesy of the artists and MOLAA. Those bonds extend to museum visitors in their “Pride Flags,” created in collaboration with artist Cecilia Koppmann and visitors who contribute fabric or decorate swatches with messages of pride, acceptance, love and advocacy to be quilted in. Recycled cloth in both their mosaics and pride flags carries the histories of those who donate to their artistic enterprise, reminiscent of Joel Otterson’s quilts, reclaimed from his grandmother’s and sewn into new works.

The exhibit includes mosaics from the “Family in 6 Colors” series, made in 2018. The pièce de résistance, California Family in 6 Colors (2019), created in residence at MOLAA, derives from David Hockney’s double portrait, Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy (1968). In the role of Barchardy, Chiachio returns the viewer’s gaze, wearing a diadem fashioned after Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt’s ornate sculptural work. Next to Giannone’s Isherwood, is a “69” à la Lari Pittman. The imagery includes references to punk front man Tomata du Plenty, Patssi Valdez, Carlos Almaraz and others.

Primary in this lineage are Hockney and Sonia Delaunay, whom the duo describe as their artistic grandparents. Delaunay’s unfettered, lyrical use of color, in discrete geometric shapes, is evident in their gamesome sense of pattern, color and design, and Hockney’s influence is seen too, in their lush color, figuration and unabashed depiction of their lives together.

-

Fred Wilson

“The aim of the dreamer…is merely to go on dreaming and not to be molested by the world… But the aims of life are antithetical to those of the dreamer, and the teeth of the world are sharp.”

This quote from James Baldwin’s 1962 novel Another Country is on the wall of Fred Wilson’s exhibition “Afro Kismet,” where its interpretation is left open. One might expect the artist to identify with the dreamer because of his deeply researched practice into museum collections and the social, economic, political and historical knowledge that illuminates objects beyond the mere cursory glance.

But Wilson’s research aims to dispel illusions. For more than 30 years, he has deconstructed museum collections to address issues of representation and the erasure of people of African descent from the histories presented within those collections.

“Afro Kismet,” originally exhibited in the 2017 Istanbul Biennial and subsequently at PACE in London and New York, now at Maccarone, examines the Venetian and Ottoman Empires, and the slave trade, as it trafficked Africans into Venice and Istanbul.

Fred Wilson, Not in a Hurry, Like From One Day to the Next, but, Every Day, Every Day, For Years, For Generations (2017), courtesy Maccarone. Wilson draws from Baldwin’s novel, which the author wrote over an 11-year period while working in Istanbul, pairing excerpts as wall text with objects in the gallery. Another text, Shakespeare’s Othello, conceptually integrates “Afro Kismet” and a companion exhibition, titled “Glass Works,” of Wilson’s Murano glass mirrors, Venetian chandeliers and black Murano glass tear-drop shapes positioned as if seeping through and dripping along the gallery walls, or surfacing amid white structural glass laid flat on the floor. The underlying presence of Othello suffuses the exhibition with a meditation on literature’s power to create profoundly lasting impacts on culture, referencing representations of “blackness” as embedded from within a Eurocentric point of view.

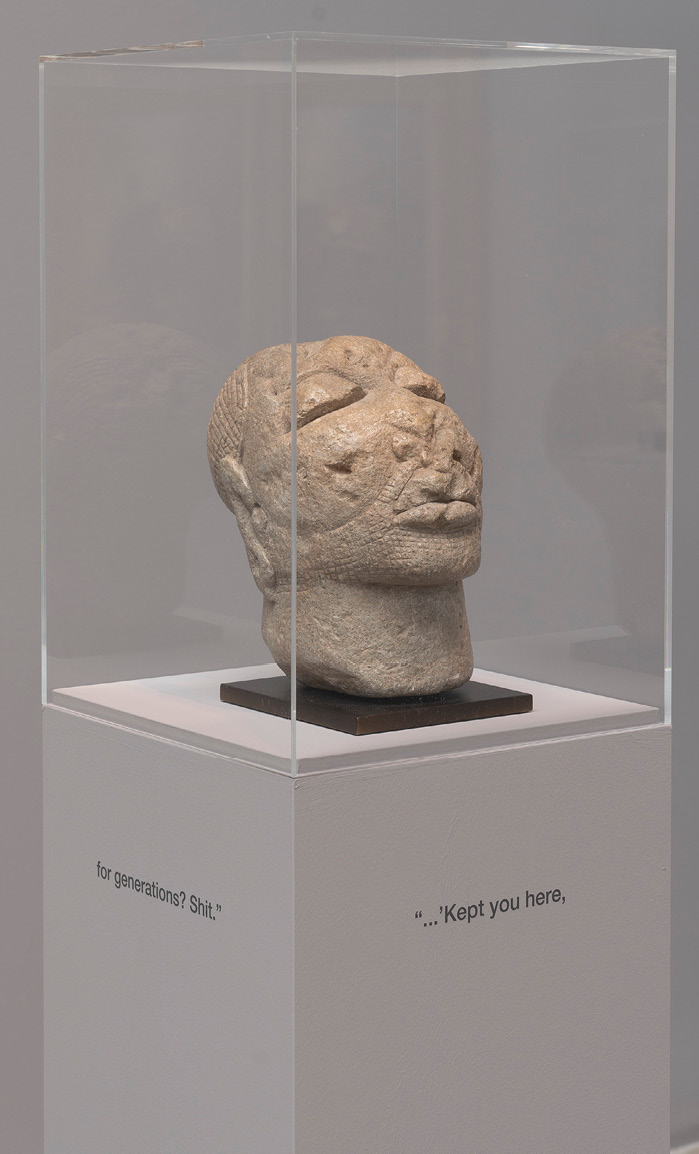

Positioning objects from the Pera Museum (Istanbul) with other contemporary and fabricated objects invites reexamination. They Passed Their Lives Thereafter in a Kind of Limbo of Denied and Unexamined Pain (2017), an arrangement of engravings and an illustration of a scene from Othello implicates depictions of Afro Turks. Wilson covered the etchings with vellum, cutting out an ellipsoid to draw attention to each instance of a miniscule black figure in the distance, away from the central figures of the compositions. Other objects, like a stone Sherbro head are paired with text (…kept you here, 2018), evoking the displacement and enduring trauma of slavery.

In “Glass Works” Wilson again exposes racializing ideas by using lines from Othello as titles. One of these (A Moth of Peace, 2018), a white Murano glass Venetian chandelier, evokes an image of whiteness as a representation of the “purity” of Desdemona. It plays off the two Ottoman-styled black Murano glass chandeliers in “Afro Kismet” (The Way the Moon’s in Love with the Dark, 2017; Eclipse, 2017) and a black Murano glass mirror (I Saw Othello’s Visage In His Mind, 2013).

In these complementary exhibitions, Wilson reclaims object and narrative, calling attention to the ways the slave trade and the African diaspora permeate the histories of global trade and culture, yet have stubbornly been overlooked as if invisible.

-

Shirley Morales and the Constant of Change

This year, the veteran LA gallery ltd los angeles marked the start of its 10th season. In some ways, the gallery’s program looks more like that of a nonprofit than a commercial gallery. They don’t represent artists, per se. Instead of having a roster of 12 to 20 artists who rotate solo exhibitions, with a few group shows sprinkled in between, ltd los angeles works with a broad range of artists, sometimes in solo exhibitions, but mostly in a schedule heavily peppered with group shows featuring edgy work. It’s a venue where emerging artists—quite a few are recent MFAs from schools like Hunter College, Yale and UCLA, such as Jule Korneffel, Ilana Savdie or the drawing collective En Plein Error—often show alongside established ones, such as Skip Arnold, or Jason Meadows.