Your cart is currently empty!

Sean Raspet Various Small Fires-LA

Sean Raspet’s debut at VSF-LA is both an invitation to critically examine anthropogenic climate change—and how we are all implicated—and a series of proposed bio- and geo-engineering solutions for ameliorating the effects of the escalating climate crisis.

Raspet’s practice is as much a record of the workings of technological systems and their linked legal and financial instruments—and as such, a cataloguing of late Anthropocene systems—as it is a making visible how petroleum dominates contemporary life. An accounting of past projects yields works on synthetic flavors that infuse food products, chemical signatures of consumer goods, and a gallery slathered with a transparent synthetic DNA gel normally used in corporate anti-theft schemas. In pulling back the curtain, Raspet points to the proliferation of synthetic (petroleum-based) molecular compounds, and how they are consumed, thus becoming substances we “metabolize.”

A visually lush installation of more than 50 genetically modified plants (∂ (various species), 2019 and ongoing) emerging from planter boxes outside and small wall-mounted containers inside, appears not as scientific display or archival catalogue, but as if each plant were a small jewel. Yet these experimental subjects have been irradiated or exposed to chemical mutagens in an effort to accelerate the occurrence of genetic mutations—the goal being to increase adaptability to a rapidly warming environment.

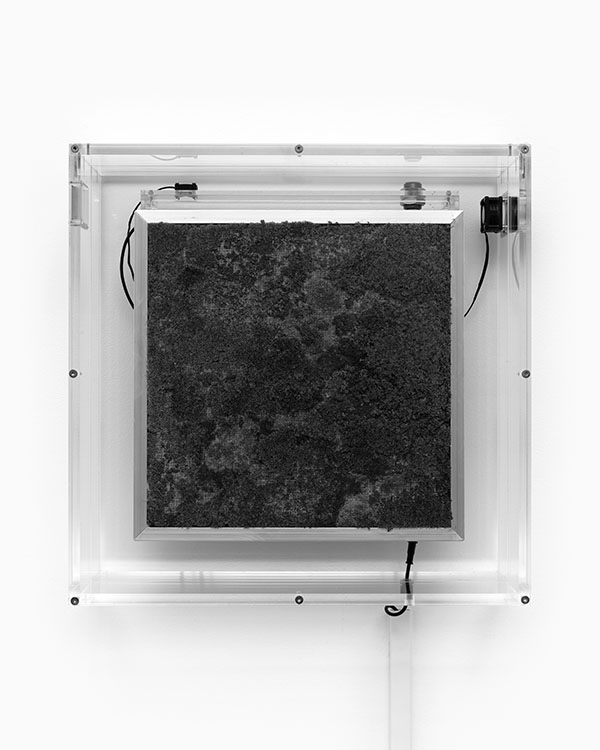

Another plant-based work gestures to natural processes supplanted by synthetic ones—and conversely, the possibility for biological processes to re-emerge. A patch of moss in a Plexiglas box with small apertures (Filter (Physcomitrium patens: patchoulol synthase-(+), linalool synthase-(+)), 2015–21) is described as a self-fabricating biological air-filtration system—a reference to the exchange of carbon dioxide for oxygen. In a nod to human/plant co-evolution, the moss is genetically engineered to emit the scent of patchouli, which the artist describes as reminiscent of a forest floor.

The third work (Atmospheric Reformulation (CO2 Direct Air Capture), 2019–21), created in collaboration with Swiss company Climeworks, is ephemeral but consequential: one metric ton of carbon removed from the atmosphere. Originating in Raspet’s “Atmospheric Reformulations” series, which investigated the creation of synthetic atmospheres and reformulating Earth’s atmosphere, it is an exemplar of planetary engineering; the captured carbon will be sequestered in volcanic rock.

Each of these works resides squarely within the realm of the anthropogenic, reflecting the contradictions of the Anthropocene; while they reveal optimism on the part of the artist, how they land is a more nuanced affair.

Whether humans are capable of doing enough to ameliorate the worst of climate change—and whether those efforts won’t be fraught with deeply problematic ethical considerations—is a trickier question. Humans’ ethical obligations to the millions of other species, plant and animal, that reside on the planet with us, and the ethical obligations of the global north, which produces the majority of carbon emissions, are quite clear. Yet will our efforts, whether in the realm of bioengineering or planetary-engineering—if we can muster the will and determination to actually make change—initiate a cascade of unforeseen consequences that are just as troubling as the issues at hand?