Your cart is currently empty!

Byline: Arthur Ivan Bravo

-

OUTSIDE LA: Jesse Mockrin

James CohanOne could see the LA-based artist Jesse Mockrin’s decision to name her first solo exhibition in New York City and at James Cohan—“The Venus Effect,” after the art historical term, motif, and visual effect—as itself a gesture towards acknowledging, even inviting ambiguity in the reception of her work. After all, the so-called ‘Venus effect,’ such as it is understood, achieves conceptual coherence only through particular scaffolding, at once disparate and contingent. Found throughout the very Renaissance-era portraiture of women that has inspired Mockrin’s work, the Venus effect refers to the employment of mirrors by painters, almost exclusively men, to reflect their female subjects, effecting an objectification fit for the male gaze. Within this reflection, however, the viewer should be able to surmise the female subject is not —perhaps only—looking at herself, but could be looking at them, if not originally the work’s creator. The encounter between perspectives orchestrated may have a beguiling effect, but ultimately the maze of gazes reveals one over the rest, sustained by the historical structures of power operating behind gender. The Venus effect is often tied to the proposition that what one believes may not correspond to reality. Its concerns reach beyond that of the artistic or historical, into the scientific and psychological. Indeed, Mockrin’s newest body of work holds promise to be about so much more than just its namesake.

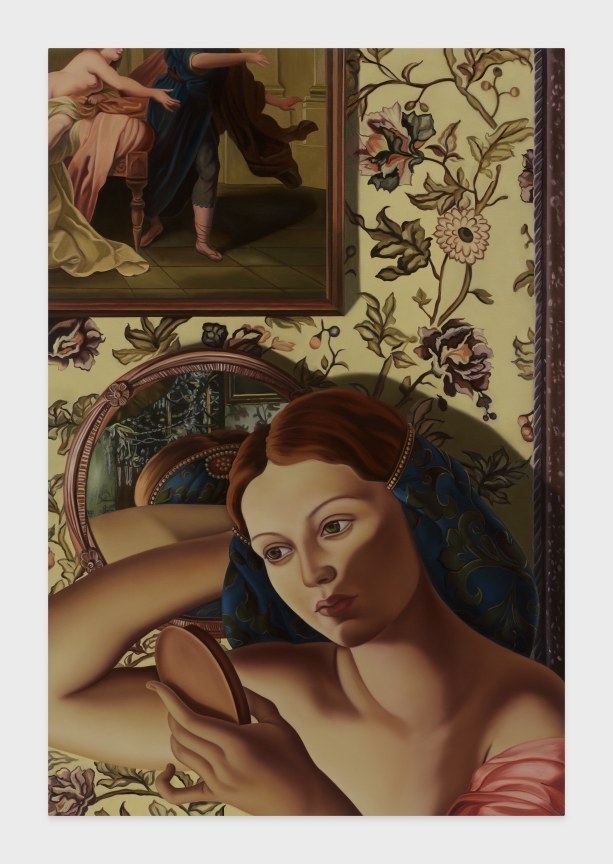

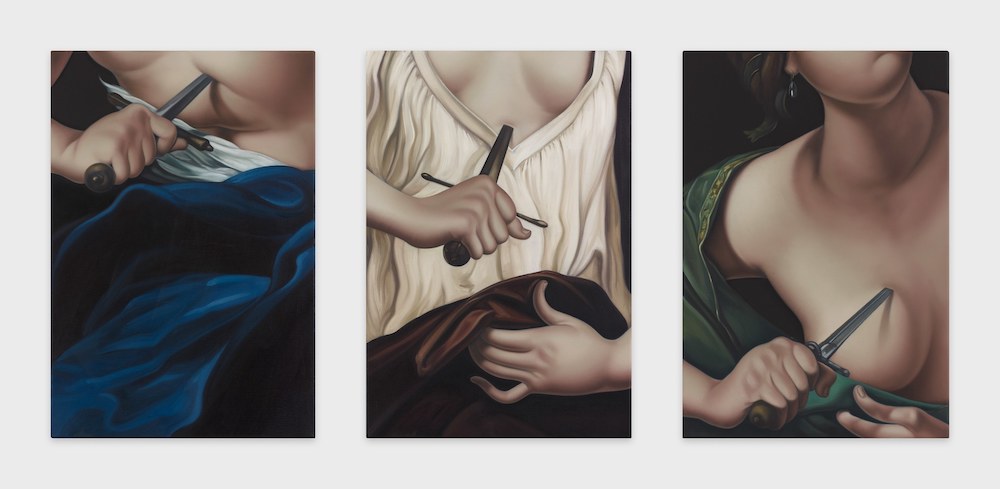

“The Venus Effect” has been installed within the James Cohan gallery so that each of its 10 paintings (all 2023) is given ample space for presence and viewing, no matter the size. All of the paintings have also been hung at heights ideal for most full-grown viewers to meet the main contents at eye level. Three are diptychs, larger in size than the rest. A handful of drawings on paper accompany the exhibition, titled, and depicting, Women grieving. It should be safe to say, as well, that by this point in her career, Mockrin has developed her own singular, or signature, style. By her own admission, Mockrin prefers more defined line work, her faces and bodies are idealized, echoing a Mannerist aesthetic, ironic, reflexive, and all, her rendering of human skin is perfectly unblemished, unreal, the result of layers of oils procedurally applied. The lighting in Mockrin’s paintings is always impeccable, true to her source material, and the better to highlight the ever-present and animated textiles, as in curtains, or the folds of clothing, and more often than not, their floral decoration. Mockrin’s compositions are often informed by the practice of cropping, if the human figure is not the focus of a given painting, a detail is, with hair and hands peripheral and cut off. Finally, the femininity on display in Mockrin’s paintings is not so much portrayed as interrogated. All if not most of these aspects are prevalent throughout the exhibition.

Jesse Mockrin, The gaping wound was exposed for all to see, 2019. Courtesy of James Cohan. Whether intentional or not, one of the first paintings the viewer is likely to meet in “The Venus Effect” is also among the more audacious. In Herself Unseen, a woman’s sideways profile occupies the bottom half of the composition, she poses her hair with one hand, while attentive towards a small mirror held with the other. Just behind her, another mirror reflects the back of her head, and the room she’s in, instead of the viewer, or Mockrin. Above her, the corner of a Renaissance painting peeks out, depicting a barely clothed woman reaching for another figure, possibly a man, who swats her away. In fact, frames—or crops?—abound, perhaps five in all. One seems to line most of the actual canvas’s right-side frame, and another is hinted at in the wall mirror’s reflection. A floral-decorated wallpaper field and antique light tie everything together. The viewer is left to ponder on the nature of framing or cropping, the question of what is included, what is left out, what is focused on and what is dismissed, namely, perspective as understood expansively yet critically. Many of the other paintings follow suit, taking up different aspects or concerns set down here. In Divination, Mannerist-style boneless arms and hands prop a mirror up, against an upside-down V-opening of curtains, and resting on a sheen surface, both decorated in floral, all of it bathed in a cold blue light. The posing of the arms is unnatural enough to highlight the composition’s framing. Much the same effect is present in “Sorceress,” where yet again, impossibly curved, bent hands pose with long wavy red hair and hold up a mirror, presumably for a face outside of the frame. Almost every surface in the room, including the hand-held mirror, has floral decoration, beautifully highlighted by sunlight streaming through a window.

In the eponymous diptych, Mockrin utilizes the gap between the two paintings to question their cumulative coherence. On the left, sunlight hits heavy drapery, a clothed arm lifts some of it up from the left, while a naked woman poses and looks at something out of frame to the right. On the right, beautiful green drapery divides perhaps that naked woman’s holding of a mirror, reflecting a, or her own, face, gazing directly at us, from an unclothed arm lifting some of it up. Taken together, it is as if the scene were a narrative loop. Presumably, we are situated in the room with them, and this is made even more surreal by the detail of a garden just outside the window, beyond our subject figure(s). If not audacious, one of the more ambitious paintings in “The Venus Effect” is The lover and the beloved, where the diptych gap suggests an in-between mirror, only to come into conflict with the daylight that streams in progressively from left to right. In both parts, a seated woman gestures down to a seemingly admiring male below her. On the left, the woman holds the mirror, the man’s back is turned to us. On the right, the male is facing us, and he is the one holding the mirror. The painting is inspired by an Italian epic poem set during the Crusades and involves chivalric knights and treacherous witches.

The paintings of “The Venus Effect” hold an abundance in potential for interpretation. What do we make of Mockrin’s highlighting of the act of cropping and framing? Furthermore, what does she want us, the viewer, to pay attention to? How can the viewer read the inclusion of snippets from famous Renaissance-era paintings and their exclusive focus on gender dynamics? Why are the people in Mockrin’s paintings modeled after the Mannerist aesthetic? Some contemporary interpretations argue Mannerism has a self-conscious, reflexive, proto-(post)-modern character…What of their unnaturally perfect skin? Why do some of her subjects defy the traditionally imposed gender dichotomy? What about the recurring gender role reversals that occur in her paintings? What kinds of questions does Mockrin have for the historical and social construction of femininity? In referencing Renaissance art as source material, is Mockrin reviving an antiquated vision for a twenty-first-century audience just to see what the reaction is? Or is satire perhaps one of her aims? Critique? The nature and execution of Mockrin’s project, overall, is such that no matter what explanations or interpretations are offered up, still others will present themselves. This is, of course, to the artist’s credit.

-

OUTSIDE LA: Greater New York 2021

MoMA PS1[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ admin_label=”section” _builder_version=”3.22″ global_colors_info=”{}” theme_builder_area=”post_content”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row” _builder_version=”3.25″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” global_colors_info=”{}” theme_builder_area=”post_content”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”3.25″ custom_padding=”|||” global_colors_info=”{}” custom_padding__hover=”|||” theme_builder_area=”post_content”][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” _builder_version=”3.27.4″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” global_colors_info=”{}” theme_builder_area=”post_content”]Having opened after an entire year’s delay even as the COVID-19 pandemic entered its third year, the fifth iteration of MoMA PS1’s signature major survey of art in New York City, titled “Greater New York 2021,” finds the curatorial team of in-house Curator Ruba Katrib and Director Kate Fowle, MoMA’s Curator of Latin American Art Inés Katzenstein, and collaborating Scholar-Curator Serubiri Moses steering a turn towards an introspective perspective rendered by, yet contingent with localized history. Citing from a personal account by Harlem-born science-fiction writer Samuel Delany, the exhibition’s organizers figure “contact” as a significant interstitial juncture that is still to be found in contemporary urban life, though precariously so. The nature of how thematic matters are explored all share of an intimacy not unlike the feel of discovering a lost personal journal, the contents within charmingly rambling. Perhaps this is where connections are made accessible, “contact” possible.

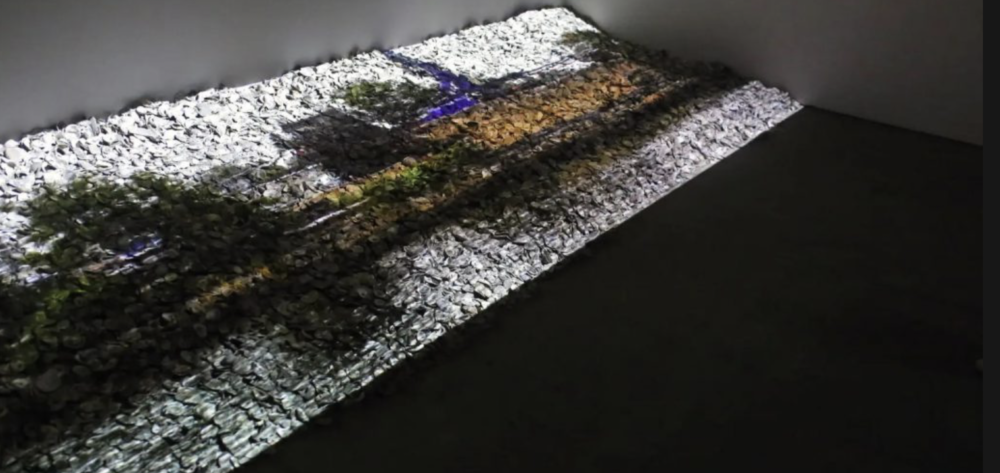

As with past editions, there are a number of entry and then exit-points to “Greater New York 2021,” which of course, further enhances the singular experience. One of the first works to be encountered may be Alan Michelson’s “Midden” (2021) (see above), an installation spanning a two-floored wall section wherein peering below from a balcony, a short documentary film depicting views of Newtown Creek and Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn is projected onto a frame-field of oyster shells below. “Midden” is the name for a shell mound of considerable size, and through the work, Michelson invokes a timeline going back thousands of years, from prehistory, through Lenape settlement, then European colonization, to present-day Brooklyn, a product of New York City’s industrialization, as native oysters have disappeared. History, if not time itself, is likewise an invocation within Mohawk-descended Shelley Niro’s photography as paleontology, Kansas-born, Chemehuevi and Anishinabe poet Diane Burns’s recitation of “Alphabet City Serenade” while walking the streets of a 1980s Avenue D seemingly in ruins, paraphernalia from the 1990s street performances of Curtis Cuffie, the sensuality of Black queerness captured in the 1980s photography of the Nigeria and England-raised Rotimi Fani-Kayode haunted by the HIV/AIDS epidemic much as the gorgeous and large-scaled abstract paintings of the 1970s and ’80s by the queer Argentine-born Luis Frangella, and Robin Graubard’s and Marilyn Nance’s decades-long photographic documentation of New York City’s punks and mafia gangsters, and the culture of its urban life, respectively, from the same decades as the former.

A more biographical aspect is articulated in the photography of Indian-born Avijit Halder (see above), powerfully capturing color and motion through the wearing of his murdered mother’s sari, or the works of Milford Graves and Paulina Peavy, inseparable from the incomparably creative and remarkable lives both artists led, the former mainly in music, and the latter in service to a UFO named Lacamo. Finally, if Yuji Agematsu’s miniature street-garbage sculptures, fitted into the wrappers of his cigarette packs, for every day of the year of 2020, does not serve as a fitting coda, perhaps Marie Kalberg’s understated yet bonkers adaptation of Doris Lessing’s The Good Terrorist does. Visibly filmed with artist friends filling in for 1980s leftist radicals-cum-terrorists in an empty Manhattan high-rise apartment during the March 2020 lockdown happening below, it more or less effects the surrealistic disorientation of the times. Or, perhaps it could be Emilie Louise Gossiaux’s multi-media conjuring of London, her yellow Labrador Retriever guide dog, through drawings and sculptures.[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

-

Lari Pittman at Lehmann Maupin NYC

Lehmann MaupinFast on the heels of Lari Pittman’s most comprehensive solo exhibition in decades, which ran until January at the Hammer Museum in the artist’s hometown of Los Angeles, “Found Buried” is his first at New York City gallery Lehmann Maupin. The exhibition features a brand new set of large-scale paintings and a subset of smaller works on paper, all of which were produced in 2020 and provide a timely, fascinating glimpse into Pittman’s practice of late. “Found Buried” resumes with the thematic concerns, graphics, materials and methods with which Pittman has long been preoccupied in his practice.

As a gay man of Colombian-American descent, many of Pittman’s concerns have manifested in the thematic content of his work: a dialogue with his own sexuality and identity. Pittman’s work has also long displayed his personal interests in historical injustices like the HIV/AIDS epidemic and those found in gender relations. This show continues this legacy of responding to legacies of past injustices — its overall iconography and aesthetic suggests themes relating to the colonial American project. The paintings are large, and half of them feature humanoid figures and familiarly rendered objects amidst seemingly chaotic compositions. The other half prominently feature Pittman’s characteristic patterns and motifs of the decorative and applied graphic arts. Accompanying the paintings are a subset of smaller works on paper, distinct in content and composition: portrait-like profiles are the center of focus, and color schemes range between muted reds and browns.

The series is split between those numbered and those subtitled. People and objects feature prominently in the former. Humanoid figures are rendered akin to straw dolls, positioned like marionettes, seemingly lifeless but not fully so. They are clothed in either Native American or colonial dress, possibly both. In Found Buried #1, a figure is splayed on the upper half of a pictorial field, looking sick or mutilated and is bent over vomiting something cryptic and flesh-colored that could be seen as an extension of its body. It is enclosed by an oval of axes and surrounded by the steeple-dome-roofs of old buildings. Elsewhere, elements such as an antique automobile, a sailboat—of the type Pittman is so fond of utilizing, a volleyball and a bird icon encased in a solid light green circle, float about. A floral pattern of muted reds, blues and whites functions as the connective tissue between the elements.

LARI PITTMAN, Found Buried #2, 2020 The evocation of a floating body or figure is echoed in #5, this time over a landscape of towns and mountains; the architecture and aesthetic of which has the feel of the rustic and folk. The figure holds a pipe in its mouth, its headdress made of feathers, unsettlingly, it is tied by its neck and limbs by rope. Doing away with full-body figures, #9 offers up an interesting arrangement of profiles similar to the works on paper, all smoking pipes and wearing feathery headdresses, Pittman’s oft-utilized lamps occupy the edges, while an abstract symbol of bright cyan against orange shocks from the homely but beautiful brown-and-gray floral pattern just beside it.

Among the subtitled paintings, Textile for Casket Lining, has Pittman composing and conjuring with sailboats and scissors, complex shapes complementing the interactions of blacks, browns and yellows, with touches of reds and blues. This imagery of domestic material culture likewise features centrally in sibling paintings like Textile for a Courtroom and Textile for a Prison, where hammers, painted eggs, straw-filled miniature birds, scissors and flowers in tones of blue pop out amidst layered patterning. The subtitles of the paintings point to the everyday goings-on of human activity—events, customs, institutions—from crib linings to courtrooms, wedding dresses, hospitals and even revolutions.

The paintings and works on paper in “Found Buried” feature much of the visual vocabulary Pittman’s work has been known for. Legacy and the contemporary are provocatively conjured through a singular iconographic-oriented idiom, potently expressed through the artist’s ever rich and intricate multimedia paintings.

-

Alice Gibney & Sarah Irvin

The two-person exhibition, “The End & The Beginning,” with works by Berlin-based, Canadian visual artist Alice Gibney and multimedia American artist Sarah Irvin, addresses themes of life and death.

Irvin’s work in the exhibit revolves around her experience of motherhood and corresponds to birth, or life. Sharing her experience of motherhood and its associated labor, she interprets, manifests and marks life using graphite and data collected on paper. Her Rocking Chair Series (2014) of graphite sketches, index time spent on a rocking chair, caring for her daughter. These were captured through the transfer of graphite as she rocked the chair. By recording this motion, in which she and others sat with her daughter, with the transfer of marks onto paper, the sketches measure time passing in life, of one person caring for another.

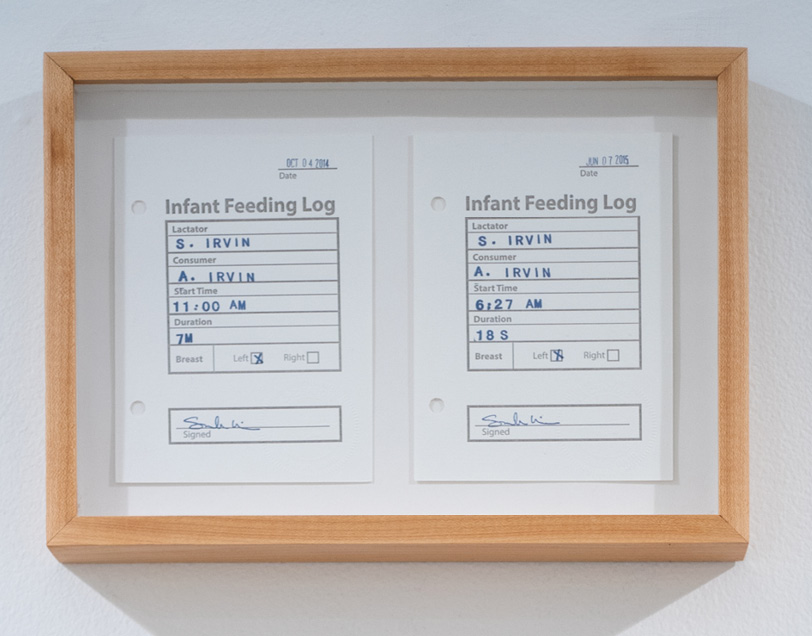

Sarah Irvin, Infant Feeding Log (2018). Both images courtesy of Massey Klein, New York. Infant Feeding Log (2018), a multimedia sculptural installation by Irvin consists of a rather intimidating catalogue. Recorded on individual index cards, the installation elaborates the specifics and lengths of time for which the artist breastfed her daughter. Complementing her feeding log, a portfolio of codified sketches of ink on paper, Breastfeeding Series (2014), is accompanied by a pair of sketches and catalogue cards framed together. Together, these works capture and illuminate, or at least memorialize, intimate moments of life, which are often lost in the passing of time. In focusing our attention on not just the ephemera, but the actual relations of the individuals involved, she calls attention to the significance of these seemingly simple actions.

The Berlin-based, Canadian visual artist Alice Gibney presents a series of charcoal, ink and pencil sketches, and drawings on paper. These differ in size and follow a logic of coloring, offering richly symbolic depictions of figures that blur the line between dreamlike and reality.

Gibney’s large sketch, Evolving out of chaos (2014), reveals a woman either turning her head, or double-faced. She is outfitted with an impossible get-up of filled bags or sacs, fake nose and glasses dancing on her hair, hallucinatory. The visual allusions or suggestions evoke whimsy and a consideration of identity.

Opposite Irvin’s records of time, a series of almost 20 charcoal, ink and pencil sketches and drawings by Gibney investigate the considerations introduced in Evolving out of chaos. These are equally absurd, touching and cryptic, served with an underlying melancholy. Most, including Gone Astray, The Forgotten Triplet reaches a conclusion, The Boobhead said nothing interesting (all 2018), depict humanoid figures in expressive postures, wearing absurd, charming getups and props, some body parts blankly uncolored, others emitting a colorful vibrancy. All are hallucinatory, while also possessing some degree of realism. The effect is haunting. Gibney reportedly produced them in response to a personal loss.

Both artists have bared themselves and invited us into their intimate worlds through their art, yet do they remain strangers? This conundrum would seem worthy of the themes and questions so artfully explored and pondered in and through their work.

-

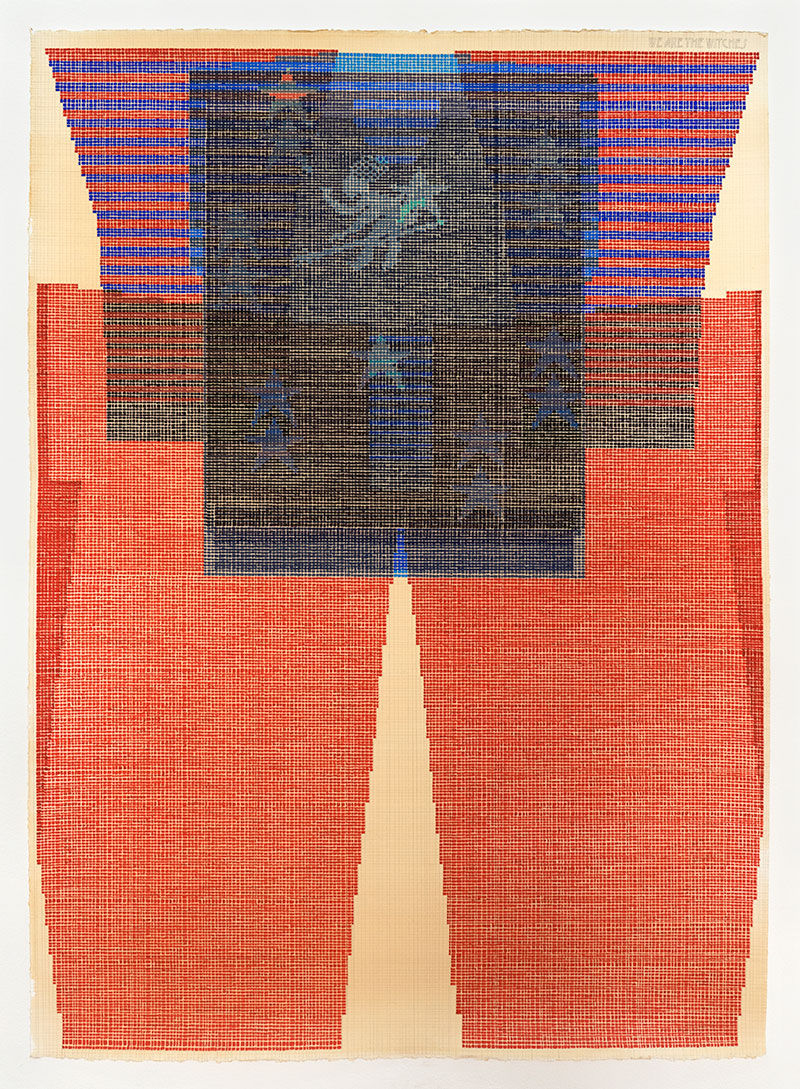

Ellen Lesperance

Ellen Lesperance has never trod lightly when imparting the social and political beliefs, inspirations and intentions guiding her practice. Raised in Seattle and based in Portland, Lesperance has been consistently straightforward in pointing to her feminist mother and growing up in a mixed-race family as factors in steering her interests towards feminism and sociopolitical activism, the latter having to do with the ethics and strategies of “creative direct action.” So informed, technically, Lesperance’s practice employs Symbolcraft, a grid-oriented traditional means of communication inherent to and utilizing the practice of knitting by way of meticulous painting because, the artist claims, knitting is historically women’s work, not beholden to a patriarchal tradition of practice. Among her stated aims is the desire to rescue any aspect of female activists, including clothing, which may otherwise be lost to the selective tendencies of official histories.

For “Lily of the Arc Lights,” her first solo exhibition in New York City, Lesperance continues to make use of Symbolcraft in interpreting, memorializing and activating the agency of the individuals and artifacts of feminism and activism. In this instance, Lesperance narrows her scope towards the particular yet vast subject of Greenham Common—the former a territory in Berkshire, England, with a lengthy, contested history—and its women’s peace camps, the latter’s response revealing what makes that history worthy of attention. In fact, that history spans centuries, alternating between popular and wartime uses, as determined by respective governments. In 1980, during the Cold War, the territory came to house the largest stockpile of nuclear missiles in Europe. The following year, women’s peace camps surrounded its perimeter, setting the stage for nearly 20 years of remarkably creative protests.

Ellen Lesperance, How Does It Feel in Your Chicken Coop, Soldiers? Little Macho Cockrells Parading the Wire? Strutting in Your Dustbowl, Arid and Treeless, You Obey Orders but We Are Free! (2018), courtesy Derek Eller Gallery, photo by Robert Wedemeyer. “Lily of the Arc Lights” consists of 10 new paintings of gouache and graphite on tea-stained paper, one accompanied by its sweater realization. Not only do the paintings evoke an earthy, painstaking process in interpreting memory and recorded media, they contain hollowed-out Desdemona-font texts, such as the colorful, graded and abstracted As If The Earth Itself Was Ours By New Covenant (all works 2018). We Are The Witches reflects a child-like motif of a witch riding her broomstick in the nighttime sky, surrounded by large, crooked stars, cloaked in blues above reds. Stay Safe contains those very words in its grid-like patterns, along with images of a peace dove, a peace sign, and a blazing rocket, with monochrome abstract shapes surrounding. Shall There be womanly times? Or Shall We Die? posits its question through imagery of mountainous landscape under starry sky in blues and browns, and Fireworks displays beautiful, folksy, colorful arrangements of rings.

In making Greenham Common and its women’s peace camps her subject, Lesperance invokes the lives of ordinary people, and larger structures and entities of power at play in the world as real contingents, interpreted and sharpened by a process of work bound to feminist and activist perspective. In a clever stroke, we may access this all through the sweater, materialized, inviting us into the exhibition.

-

Nirveda Alleck and Eric Van Hove

Curated by Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi, and inspired by Anthony Kwame Appiah’s Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers (2006), the loosely Africa-centric, two-artist exhibition at Richard Taittinger Gallery, “Ethics in a World of Strangers: Nirveda Alleck and Eric van Hove,” involves a public intellectual, a curator and two artists, all of whom have led very cosmopolitan lives. Continuing a focus on Africa that defined “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?”, Nzewi’s 2015 survey of contemporary African art at Taittinger, the core theme for “Ethics,” is an exploration of and supportive appraisal for the outlook and culture of cosmopolitanism—the idea that we are all citizens of a common human community that is sustained through mutual ethical understanding.

Juxtaposing the very different work of van Hove and Alleck, Nzewi’s intention seems to be for a productive dialogue; both artists arguably start with a concern for community, with an aim towards clarifying and reconciling the tensions and interdependencies for the micro and macro, in an age of globalization.

Van Hove’s sculptural installations, placed on pedestals and concentrated mainly in the front of the gallery, are overlooked by paintings from Alleck’s “Continuum” series, which has been ongoing since 2006. These realistic, figurative works depict different populations–perhaps African locals, and European tourists. There are families, parents, children and older couples, with clothing giving away possible clues to their identities. Interestingly, the backgrounds in each painting have been completely erased, or have not been painted at all. One of its many effects is that the figures from any one of the paintings could be exchanged for those from another without much of a difference to either painting.

Nirveda Alleck, Continuum Dakar, 2017, courtesy of Richard Taittinger Gallery The effect of van Hove’s engine parts assembled from local materials is that of a curiously charming Frankenstein-like creation. There is the obvious suggestion of connecting folk arts and crafts with modern technology, and a playful lifting of the veil behind the technology’s characteristic façade of perceived perfection and artificiality. On a deeper level, the combination of folk arts and crafts objects, their long histories of tradition and development, with some of the most iconic productions of modern industrial production, stages the collision between two traditions, or cultures. After all, who would have thought, or deemed it rational, or efficient, to build complex machines out of non-machine-produced components? The works on view are commentaries ruminating on the relationships not only between periods of history, cultures and globalization, but also, evidently and notably, the European and African industries. The finished motorbike on view, the Mahjouba Installation (2016), is only one among many possible culminations of van Hove’s investigations.

Van Hove’s and Alleck’s interspersed works call into question, indeed blur the boundaries between what we think of the local, with implications for how we identify ourselves, and who we feel a relationship with, potentially suggesting connections heretofore neglected or unimaginable, within an ever-increasingly interconnected, yet also unpredictable, world. -

Paul Anthony Smith

Paul Anthony Smith’s third solo exhibition at ZieherSmith represents an ultimately fruitful distillation, apparently in both the methods of his practice, and subsequently in the visual nature of the roughly dozen works that make it up. “Procession,” as Smith’s latest collection of works is titled, features the practices and mediums, visuals and themes that have characterized his art; however, in a welcome provocative development, it also finds him honing aspects of his practice.

Smith has long mined the Jamaica of his childhood and family—alongside his identity as an American and immigrant—and of his imagination, for inspiration in his paintings, prints and other multimedia works. Likewise, he has more often than not distorted and obscured what he has chosen to depict, and then layered over, overlapped or applied upon these already rich images from a limited set of patterns, themselves evocative of either scarification and the Kuba stylings of the African Congo, or physical boundaries such as cinder brick walls. These patterns have been created mostly through Smith’s trademark method of “picotage,” inspired by an 18th-century French practice associated with textile arts, in which he utilizes a ceramic tool to laboriously pick away at and from the surface layer of his photographic prints. The resulting effects can mean different things to different people: decorative, damaged, shimmering; to me they looked like tiny dabs of white paint, meticulously and strategically applied and arranged.

Paul Anthony Smith, Blurr, 2016, ©Paul Anthony Smith, courtesy of ZieherSmith, NY. For “Procession,” Smith has focused on particular aspects of his practice even as he has transcended its boundaries. The locations and events the photographs which make up the ‘body’ of the exhibition were taken in and of—Vieques, Puerto Rico, and Brooklyn’s 2016 West Indian Day Parade—suggest Smith’s geographical and cultural interests expanding beyond Jamaica, towards the pan- or diasporic Afro-Caribbean world. In works citing Miles Davis and John Coltrane compositions, for example Kind Of Blue I and II (2016), which consist of blurred picturesque tropical snapshots picotaged with abstract brick wall patterns, nature now shares as much visual representation as the human subjects that have always interested Smith; other works, like Giant Steps, So What, and Afternoon Brew (all 2016), all of which impose Caribbean carnival scenes onto those of tropical-esque nature, centering on female dancers, introduce a newfound enthusiasm for the kaleidoscopic. In all of the aforementioned works too, Smith is found to have further mastered and refined his picotage process, effecting a heightened juxtaposition between abstract and more figurative elements.

Alongside his continued employment of brick wall imagery, representative of boundaries, Smith has introduced that of chain-link fencing on works such as ‘Manhood,’ and in the 6-part ‘Blurr’ series, where images of scenes are obscured to unrecognizability, becoming compositions of color, glimpsed through a pattern spray-painted in the style of said fencing. Collectively, Smith’s receptiveness to new locales—both literally and conceptually, and the maturation of his unique methods and skills, all herald an artist coming into his own, all while in the thick of developing his practice.

-

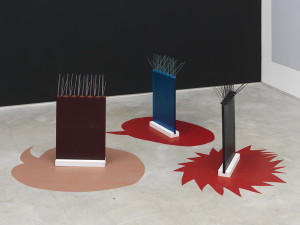

Julieta Aranda

The New York and Berlin-based artist and e-flux mainstay Julieta Aranda has long been concerned with the workings of the social arena through its medium of human interaction, and its reciprocal relationships with both the production of the self as subject, and the space within which these very subjects interact. Aranda’s practice has demonstrated not so much an aversion to producing material, as an attraction to evoking the immaterial nature and subject matter of social concepts whilst utilizing material(s) in realizing her creative intentions.

Julieta Aranda, 54H – SURVIVABILITY I had no idea of what I was supposed to want, but knew better than to admit it., 2016, ©Julieta Aranda, courtesy of James Fuentes Gallery, New York. In Aranda’s current solo exhibition, “Swimming in Rivers of Glue (an exercise in counterintuitive empathy),” she narrows her conceptual and geographical scope to an investigation of how urban spaces have been affected by the proliferation of what is termed defensive, or hostile, architecture—a design scheme imposed and implemented by governments and corporations to control human behavior. In effect, the control of subjects according to privatized interests realizes the kind of space against which Aranda has been arguing throughout her work.

Although it consists entirely of new work produced in 2016, “Rivers of Glue” loosely echoes the composition and layout of Aranda’s 2014 installation “Stealing one’s own corpse (An alternative set of footholds for an ascent into the dark).” In fact, the video projection around which the rest of the exhibition arguably revolves is titled as a sequel to the aforementioned installation, with the addendum of Part 2—Swimming in rivers of glue—The perspective of perspective. The nearly 10-minute composite of video, images and text more or less takes up where its predecessor left off, expanding from the themes of space exploration and colonization. In it, insects tear apart and devour larger creatures; images displaying the diversity of life forms on Earth are intercut between depictions of animals, diseases, and deformities; texts relay propaganda for human exploration, colonization and domination; and anonymous interviewees discuss the most urgent, distressing issues of humanity. All of the content augments a sense of dread and anxiety about the human condition, which pervades the film throughout.

As if amplifying one of the core themes driving the film, the works surrounding the projection weave together and conjure an atmosphere of tension. Each formation of the “PLACEMENT” series scattered about the floor is named after and invokes an actual environment—Japan, London or Guangzhou,—while directly imitating some of the most common manifestations of hostile architecture, from fields of studs, cones and balls, to spikes spread over grounds. Employing a concept once utilized before, the large, unfinished crossword puzzle overlooking the gallery floor, PRODUCED, provides the semiotic, discursive base for the tense atmosphere.

One of the more notable works in the gallery space, EXISTENCE, consists of the deflated artificial silhouette of a human figure draped over a bench shaped so as to discourage sleeping, seeming to question the presence of a human being, or humanity. Indeed, one of the primary concerns of the exhibition may have to do with the experience of space, when, in seeming violation of its very nature, it is employed as a means of subjugation and control.