Your cart is currently empty!

OUTSIDE LA: Greater New York 2021 MoMA PS1

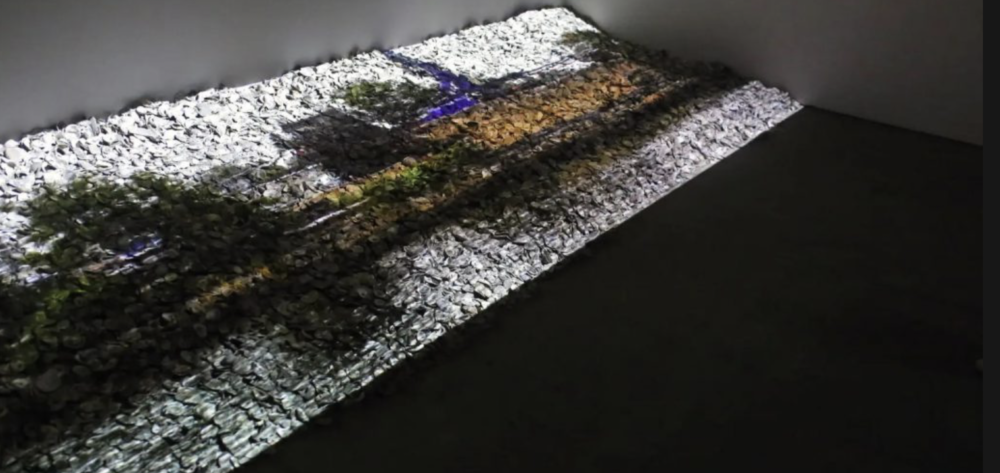

As with past editions, there are a number of entry and then exit-points to “Greater New York 2021,” which of course, further enhances the singular experience. One of the first works to be encountered may be Alan Michelson’s “Midden” (2021) (see above), an installation spanning a two-floored wall section wherein peering below from a balcony, a short documentary film depicting views of Newtown Creek and Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn is projected onto a frame-field of oyster shells below. “Midden” is the name for a shell mound of considerable size, and through the work, Michelson invokes a timeline going back thousands of years, from prehistory, through Lenape settlement, then European colonization, to present-day Brooklyn, a product of New York City’s industrialization, as native oysters have disappeared. History, if not time itself, is likewise an invocation within Mohawk-descended Shelley Niro’s photography as paleontology, Kansas-born, Chemehuevi and Anishinabe poet Diane Burns’s recitation of “Alphabet City Serenade” while walking the streets of a 1980s Avenue D seemingly in ruins, paraphernalia from the 1990s street performances of Curtis Cuffie, the sensuality of Black queerness captured in the 1980s photography of the Nigeria and England-raised Rotimi Fani-Kayode haunted by the HIV/AIDS epidemic much as the gorgeous and large-scaled abstract paintings of the 1970s and ’80s by the queer Argentine-born Luis Frangella, and Robin Graubard’s and Marilyn Nance’s decades-long photographic documentation of New York City’s punks and mafia gangsters, and the culture of its urban life, respectively, from the same decades as the former.

A more biographical aspect is articulated in the photography of Indian-born Avijit Halder (see above), powerfully capturing color and motion through the wearing of his murdered mother’s sari, or the works of Milford Graves and Paulina Peavy, inseparable from the incomparably creative and remarkable lives both artists led, the former mainly in music, and the latter in service to a UFO named Lacamo. Finally, if Yuji Agematsu’s miniature street-garbage sculptures, fitted into the wrappers of his cigarette packs, for every day of the year of 2020, does not serve as a fitting coda, perhaps Marie Kalberg’s understated yet bonkers adaptation of Doris Lessing’s The Good Terrorist does. Visibly filmed with artist friends filling in for 1980s leftist radicals-cum-terrorists in an empty Manhattan high-rise apartment during the March 2020 lockdown happening below, it more or less effects the surrealistic disorientation of the times. Or, perhaps it could be Emilie Louise Gossiaux’s multi-media conjuring of London, her yellow Labrador Retriever guide dog, through drawings and sculptures.[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]