For those of us who have followed Yuja Wang’s career for the last 15 years or so (at least since her major American orchestral debuts) and especially over the last five, we have more or less come to expect two things: to be dazzled and to be surprised.

Los Angeles audiences (who—it always amazes me—can be shocked) occasionally seem to make as much of her performance attire as her playing. At her 2011 Hollywood Bowl debut, the abbreviated length of her dress aroused almost as much comment as her playing.

No one has ever failed to notice her playing, though—which in the years since her first American orchestral appearances has placed her in a class all by herself. Always a remarkably self-assured virtuoso, she has also been consistently adventurous, continuously taking on fresh challenges both technical and artistic; and she clearly takes great delight in fresh discoveries. In the artistic stratosphere she now inhabits what has evolved over the last five years or so is a kind of playfulness, a delight in surprising both herself and her audiences.

Her last recital in February of 2020 was not necessarily programmed to surprise (though certainly, given its eclectic scope and staggering technical (and mnemonic) challenges, it pretty much floored everyone). But not much more than a minute before stepping onto the stage, she announced over the auditorium’s P.A. that she would be playing the program randomly as her mood might dictate. The cumulative effect was alternately meditative and, as the program moved into its corruscating late romantic and 20th century repertoire electrifying. By the evening’s end, between Ravel, the Alban Berg Opus 1 sonata and two Scriabin sonatas (including the F# major), it was as if the auditorium had opened into an aurora borealis.

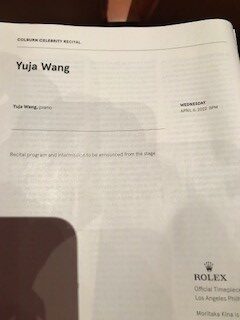

This past Wednesday night, the audience opened their programs to a blank page, rendering the standard advisory, “Programs and artists subject to change,” all but absurd. Meditative? Maybe—but also a playful contest of chance: get in the car and let me take you for a ride. Then Wang walked onto the stage in a sheer, lacy bodysuit and sat down to an assertive reading of a Beethoven sonata (No. 18 (Op.31, No.3) in E flat major). Just guessing that it wasn’t an actual ‘reading’—but it might have been; and here another first. This was the first time I had ever seen her play with an iPad on the piano music stand (although she has used music in live performance before—usually loaded onto an iPad or similar electronic screen). This isn’t a big deal in the contemporary music world. Throughout the 20th century and right up to the present, as contemporary music has become less conventionally melodic or harmonic, more complex and harmonically dense, and frequently atonal, it has become more common for musicians, including soloists, however photographic their memories, to play with the printed music. (Long before mid-20th century, Sviatislav Richter had insisted upon it, whether for Prokofiev or Rachmaninov or earlier classical and romantic repertoire.) More than a few of my pals remarked on how daunting the sheer feat of memorizing that earlier February 2020 recital program must have been. So here was Wang—for all practical purposes dressed as an aerialist—with safety net (not that she’d ever need one) securely in place. Let the playtime begin.

This past Wednesday night, the audience opened their programs to a blank page, rendering the standard advisory, “Programs and artists subject to change,” all but absurd. Meditative? Maybe—but also a playful contest of chance: get in the car and let me take you for a ride. Then Wang walked onto the stage in a sheer, lacy bodysuit and sat down to an assertive reading of a Beethoven sonata (No. 18 (Op.31, No.3) in E flat major). Just guessing that it wasn’t an actual ‘reading’—but it might have been; and here another first. This was the first time I had ever seen her play with an iPad on the piano music stand (although she has used music in live performance before—usually loaded onto an iPad or similar electronic screen). This isn’t a big deal in the contemporary music world. Throughout the 20th century and right up to the present, as contemporary music has become less conventionally melodic or harmonic, more complex and harmonically dense, and frequently atonal, it has become more common for musicians, including soloists, however photographic their memories, to play with the printed music. (Long before mid-20th century, Sviatislav Richter had insisted upon it, whether for Prokofiev or Rachmaninov or earlier classical and romantic repertoire.) More than a few of my pals remarked on how daunting the sheer feat of memorizing that earlier February 2020 recital program must have been. So here was Wang—for all practical purposes dressed as an aerialist—with safety net (not that she’d ever need one) securely in place. Let the playtime begin.

The Beethoven reading was assertive, but calm and deliberative, nothing rushed about it, including its ornaments, saving the fireworks for the super-fast final movement with its rocking triplets, jig-like rhythms, and streams of ascending and descending grace notes (and a finish that would have delighted Richter himself). From Beethoven, she moved on to Schoenberg. That was about as far as I got in identifying it until intermission when with the help of two other audience members I finally figured out it was the Opus 25 suite for piano, a landmark 12-tone work for piano. (Which means that Wang effectively turned the tables on what another famous pianist and Schoenberg fan once called “six movements in search of an audience” by sending half her audience rifling their memories for its correct identification.) Truth be told it couldn’t have been more than the third time I’d ever heard it played—including the Gould rendition. (So when was the last time you heard Schoenberg, much less played him?) She closed what seemed a short first half with what seemed a long-ish suite of piano études (or was it a kind of ‘sonata’?)—but whose? Fortunately, I was only three rows back from Los Angeles Times music critic Mark Swed—and trust him to know: they were by György Ligeti. It’s embarrassing to admit that aside from the Atmosphères (a relatively early work) and some of his music for film scores, I know little of Ligeti’s work. What in the playing sounded like four études were in fact only two: the No. 6, Automne à Varsovie and No. 13, L’éscalier du diable. They lived up to that second title—a devil’s staircase and conceivably a double one. Setting aside the notable dazzle of their chromatic progressions, I can scarcely comment; but it’s safe to say that Wang’s interpretation was true to every note.

After an intermission abuzz with everyone comparing notes, the second half began in more familiar Wang territory—Scriabin, specifically, the F# minor sonata (No. 3, as if following up on the F# major she had played in 2020—and easily as complex). This wasn’t too hard to guess, especially given a kind of vague rhythmic echo back to the Beethoven E-flat major—yet as always, Scriabin keeps us guessing, modulating into the relative major key and building up a kind of melodic fragment, before further modulating into darker harmonic excursions both major and minor that build, break down and build yet again. Wang makes all of this feel practically seamless while losing nothing of the dramatic fire and nuance or the delicate evocations of everything from Chopin to Brahms. It feels like everything is on the line in this work and Wang held nothing back.

I recognized the work that followed as Albéniz and probably as some part of Iberia. The question was what part exactly. (I sometimes forget that Iberia is not two, not three books—but four.) Then as it moved through its harmonically shifting, dramatically syncopated sections, I had second thoughts. This flamenco drama, this passion—Albéniz?—impossible! Certainly not Granados—but could it be de Falla? I voiced my doubts after the recital to my companion. This was Wang with both hands in the fire—Albeniz’s as it turned out (Book III No. 3, “Lavapiés”).

Wang closed her program with two Preludes (Op.53, Nos. 10 and 11) by Nikolai Kapustin, a composer I knew almost nothing about—and can offer no excuse for my ignorance. Googling his name immediately after the Disney Hall press team released the program and encore selections later the next day, I learned that Marc-André Hamelin, among others, had recorded some of his music in the early 2000’s. A piano (and composition) prodigy, the Ukrainian-born Kapustin discovered jazz while a student at the Moscow Conservatory in the 1950s. For a time after finishing his studies, he was a jazz arranger in Russia and had his own jazz quintet in Moscow before incorporating bluesy jazz riffs and motives into quasi-classical musical structures. Kapustin’s music should have been surging in the fusion-fired 1970s, but seems to have languished outside Russia and Ukraine after that period, although he was actively composing well up to at least the turn of the century. The first of these preludes has a kind of Tin Pan Alley energy moving up and down the piano in broken chord progressions encompassing a range of musical notions from Gershwin to Bernstein to Shostakovich. The No. 11 Prelude is an almost quintessential blues lamentation, relieved by a slightly eccentric syncopation. In my ignorance, I half-thought Wang might be entirely improvising. (It wouldn’t have surprised me.) But no—this was the music (confirmed by the hands of Kapustin himself).

Wang closed her program with two Preludes (Op.53, Nos. 10 and 11) by Nikolai Kapustin, a composer I knew almost nothing about—and can offer no excuse for my ignorance. Googling his name immediately after the Disney Hall press team released the program and encore selections later the next day, I learned that Marc-André Hamelin, among others, had recorded some of his music in the early 2000’s. A piano (and composition) prodigy, the Ukrainian-born Kapustin discovered jazz while a student at the Moscow Conservatory in the 1950s. For a time after finishing his studies, he was a jazz arranger in Russia and had his own jazz quintet in Moscow before incorporating bluesy jazz riffs and motives into quasi-classical musical structures. Kapustin’s music should have been surging in the fusion-fired 1970s, but seems to have languished outside Russia and Ukraine after that period, although he was actively composing well up to at least the turn of the century. The first of these preludes has a kind of Tin Pan Alley energy moving up and down the piano in broken chord progressions encompassing a range of musical notions from Gershwin to Bernstein to Shostakovich. The No. 11 Prelude is an almost quintessential blues lamentation, relieved by a slightly eccentric syncopation. In my ignorance, I half-thought Wang might be entirely improvising. (It wouldn’t have surprised me.) But no—this was the music (confirmed by the hands of Kapustin himself).

Wang’s encores took on a bluesy cast, too, including Michael Tilson Thomas’s lyrical and ironic “You Come Here Often?” finally circling back to the electrically percussive Toccatina from Kapustin’s Eight Concert Studies for Piano, op. 40 – III. Toccatina—a show piece Wang has encored with before, but carrying that much more emotional freight in the wake of everything Wang’s breathtaking music-making chased from our minds—if only for that evening.

Wang’s encores took on a bluesy cast, too, including Michael Tilson Thomas’s lyrical and ironic “You Come Here Often?” finally circling back to the electrically percussive Toccatina from Kapustin’s Eight Concert Studies for Piano, op. 40 – III. Toccatina—a show piece Wang has encored with before, but carrying that much more emotional freight in the wake of everything Wang’s breathtaking music-making chased from our minds—if only for that evening.

Wow, a polished review of an accomplished performance by Yuja of Rachmaninov’s Piano nimber 2.