Years of hard work and experimentation by April Street have coalesced in her most recent solo exhibition of four paintings and two sculptural installations titled A Vulgar Proof, after an Elizabethan phrase meaning “a common experience.”

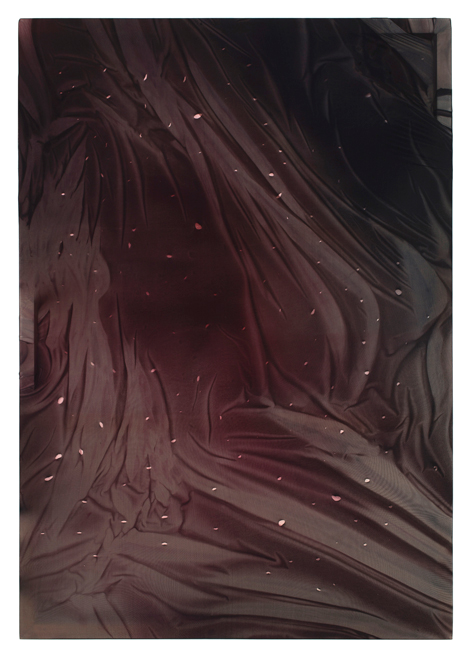

Dark, sultry and multi-layered, the four painted canvases immediately catch and hold one’s attention. What appear to be swirling patterns of paint are obscured by swaths of hosiery that are sensuously draped and stretched over them. Holding each composition intact is a single sheet of black nylon, stretched over the whole of the canvas and then dotted with small holes and tears that offer slutty glimpses into the work’s interior. One gazes at what is offered and wonders at length about the parts that can’t be seen.

Named after constellations that were in turn named after mythological figures, each painting is filled with movement, longing, seduction and elusiveness, evoking messy human encounters as well as the mysteries of stargazing. Doubt is constantly raised as to what exactly is going on; the corner of one painting bears a large and mysterious indentation, while other paintings reveal either more or less of an underlying pattern.

April Street, Antares (the heart of the Scorpion), 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Carter & Citizen.

Not long ago, Street’s work was very much about surfaces, playing exuberantly with bright colors and patterns on sprawling canvases. In 2011, her painting method took a decidedly inward and experimental turn when she devised her now signature method of wrapping herself in layers of nylon and recreating her own sleeping positions in a pool of paint, then using those same streaked nylons as compositional materials.

Her 2012 show at Carter & Citizen, titled Portraits and Ropes, featured streaked fabrics that were draped on canvases like shawls, and two dramatic pieces in which the fabric was twisted into skeins and hung. For A Vulgar Proof, Street has discarded the outward expressiveness of those works in favor of holding back and developing a deeper interior dialogue. The result is a richer and more sophisticated body of work that smartly evokes the histories of abstract painting, conceptual art and feminist performance work, but imitates none.

April Street, Cassiopeia loves Grimaldi (detail), 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Carter & Citizen.

Cassiopeia Loves Grimaldi, a pair of wall-mounted bronze Elizabethan collars, continues Street’s manipulation of the residual associations we bestow on articles of clothing. Named after two historical members of the ruling class, the sculpture isolates and objectifies a symbol of their rank, rendering it odd and specimen-like. More sweeping is Carving 100, Six in my bed, a ceiling-to-floor installation in which waxed silk threads hang from meat hooks and are weighted to the ground by pieces of soap stone, a traditional carving material from Street’s native Appalachia. One set of threads is further embellished by weaving in 100 bronzed birthday candles. Again, Street plays with the emotional and social charge of objects, deftly weaving personal associations with historical ones.

A few years ago, some might have referred to Street’s paintings as decorative. Now, she is more likely to pull elements of decor from culture and history and uncover the darker, dirtier and more complex impulses that hide in their corners.