Your cart is currently empty!

Month: April 2013

-

MEXICO as MUSE

“Mexico is truly the promised land for abstract art.”

Anni & Josef Albers, 1936“Mexico is the most surrealist country in the world.”

Andre Breton, 1938Why Mexico? It was not only that Mexico was nearby and easily accessible to U.S.–based artists, although that was certainly true. And it was not just that Mexico had powerful ancient arts that were alien and mysterious to the Euro-American public, though that was true as well. It was also that Mexico was, in the 1920s, a significant cultural center. As historian Amy Lifson notes in “Art of Influence” from 2010, “[O]ne of the hottest venues in the art world was the Mexican Ministry of Public Education, where Diego Rivera was painting the frescoes that would revive mural painting in the West. Rivera was world-famous, considered one of the three great living artists—the other two being Picasso and Matisse. It took him seven years to paint the cycle, which consisted of 235 panels. Artists, intellectuals, students, and curiosity-seekers from all over came to see the work.” Rivera’s work employed a new stylistic language, combining the European avant-garde with Mexican indigenous traditions. The following is a short survey of artists and the years they were in Mexico, where they were inspired and transformed.

Tina Modotti, Mexican peasants reading El Machete, 1928, © The Estate of Tina Modotti EDWARD WESTON & TINA MODOTTI,

1923–27

Weston and his model/lover/muse Modotti sailed to Mexico in 1923, the year Rivera began his work at the Ministry of Public Education. They met the muralist, as well as his revolutionary colleagues and the woman who would become Rivera’s wife not once but twice, Frida Kahlo. The years in Mexico transformed both Weston and Modotti. Weston moved from Pictorialism to the hard-edged formalism of his great mature work. “How ridiculous a ‘soft focus’ lens in this country of brilliant light, of clean-cut lines and outlines,” he wrote in his Daybook. Modotti went from photographic subject to photographer in her own right, producing what may be the quintessential portraits of the newly empowered Mexican people.JUNE WAYNE, 1936

The same Ministry of Education that hired Rivera to adorn its walls gave Chicago-born June Wayne a grant to travel to Mexico City and produce an exhibition of Mexico-themed work. Two employees of the Ministry met Wayne at her first one-person exhibition, a series of small works she later called “execrable” abstractions. In Mexico, witnessing the painful difficulty of poverty and homelessness, she began the expressive figuration that initiated her Social Realist phase. Mexican critic Jorge Juan Crespo de la Serna wrote of “vehement sensitivity” and “perspicacity” in the work, concluding that Wayne was “on the threshold of a great triumph.” Indeed, Wayne returned to the United States, was hired by the Federal Art Project, flourished artistically and never produced another “execrable” canvas.ANNI & JOSEF ALBERS, 1936

I opened this essay with a quotation from a letter the Albers sent Wassily Kandinsky during their first trip to Mexico. “Mexico is truly the promised land for abstract art,” they wrote in 1936, “for here it has existed for thousands of years.” Josef created his first abstract oil paintings in Mexico. Anni incorporated elements drawn from serapes and temple facades into her designs. The 2007 exhibition “Anni y Josef Albers: Viajes por Latinoamerica” paired Albers abstractions with photographs of geometric configurations in pre-Columbian pyramids and indigenous back-strap loom textiles, clearly establishing the linkages. (Although they were in Mexico at the same time as June Wayne, the Albers did not meet her there. Years later, she invited both artists to come to Los Angeles and work at Tamarind Lithography Workshop.)ANDRÉ BRETON, 1938

The Pope of Surrealism came to Mexico as a cultural ambassador of the French government. He stayed with Rivera and Kahlo, traveled through native villages in Michoacan, collected folk art, and wrote a revolutionary tract with Leon Trotsky. He also curated an exhibition of Mexican Surrealism, including not only the magnificent double self-portrait Dos Fridas (painted specifically for Breton’s show), but also several stunning works by Manuel Alvarez Bravo (whom Breton, in his typical aggrandizing way, claimed to have “discovered”).Although Breton created a significant amount of visual art, he is much better known as a poet and artistic powerbroker. He should also be credited with putting Mexico at the center of the Surrealist map—and thereby attracting numerous non-Mexican artists to its “marvelous” terrain. Among the many European Surrealists who immigrated to Mexico and found inspiration in her welcoming arms were Luis Buñuel, Leonora Carrington, Wolfgang Paalen, Alice Rahon, and Remedios Varo.

Robert Motherwell, Poncho Villa, Dead and Alive, 1943 ROBERT MOTHERWELL, 1941

Although Motherwell had longed to be a painter, his father pressured him to do something “practical” instead. In 1940, he went to Columbia University to study with Meyer Schapiro and become an art historian. While in New York, he met and befriended many of the expatriate Surrealists, including Breton, whom he found “difficult,” and Chilean painter Roberto Sebastian Antonio Matta. He and Matta spent the summer of 1941 in Mexico. Motherwell later said (in his oral history for the Archives of American Art), “It was there that I really seriously started painting. And wrote my father that I was going to quit school and paint. By that time he was beginning to feel that everything might turn out all right […] So he said, ‘Fine, if that’s what you want to do, do it and I’ll give you your fifty dollars a week.’”RUTH ASAWA, 1945-47

Asawa left the wartime Japanese interment camp her family resided in to go to teachers’ school and then on to Black Mountain College. There she studied with the Albers, among others. She traveled to Mexico in 1945 and again in 1947. On her second trip, she learned the crocheting technique that she would later use for her astonishing wire sculptures.

HANS BURKHARDT (1904-1994)

BURIAL OF GORKY, 1950

Oil on Canvas

Collection: Philadelphia Museum of Art

Courtesy: Jack Rutberg Fine Arts, Los AngelesHANS BURKHARDT, 1950-68

Burkhardt traveled to Mexico in 1950, soon after hearing of the death of Arshile Gorky, his teacher, friend and frequent collaborator. It was there that he found the visual language to deal with the devastating personal loss. Inspired by Mexican funerals and cemeteries, he began two of his seminal series: “Burial and Journey into the Unknown.” Burkhardt returned to Mexico again and again, sometimes staying as long as six months. It was in 1968 that he began to work with the discarded skulls he had collected in Mexican cemeteries. (At that time, when families could no longer make payments on graves, the tomb was emptied and the bones piled at the rear of the cemeteries.) Affixing the skulls to a large canvas, Burkhardt created what may be his masterpiece: a protest of the Vietnam War entitled My Lai. In the catalog to Burkhardt’s “Black Rain” exhibition, art historian Donald Kuspit describes My Lai “among the greatest war paintings.”

J.Michael Walker, Zan ca tlaquetchol (Portrait of Mascara Roja), 1994

Color pencil on rag paperJ. MICHAEL WALKER, 1974 to present

Walker was attending art school in Oklahoma when he was hired to travel to Sisoguichi, Chihuahua, in Northern Mexico and work as illustrator of what would become the first textbook in the Tarahumara language. His first day in the tiny village, he met the young woman who would become his wife. Walker was scheduled to be in Sisoguichi two weeks, but ended up staying eight months. He found himself spiritually and culturally reborn: “Everything I’ve done since then I attribute to that blessed ‘bump on the head’ encounter. I was at a dead end. Mexico gave me a template for understanding life and moving on.” Walker drew with color pencil in large sketchbooks, creating portraits and interiors that would become the basis for his contemporary practice. He copied pre-Columbian warriors from a reproduction of Codex Nuttall, colonial sculptures from the local church, and saints from the chromolithographs Sisoguichans hung on their walls.This list could be much more extensive. I could, for example, mention Lari Pittman and Roy Dowell, who have traveled to Mexico regularly since the late 1970s, noting that Mexican motifs appear in both of their works. I could talk about the Mexican precedents for Peter Alexander’s black velvet paintings. Or I could discuss the Mexican viceregal sources of so much of Matthew Couper’s oeuvre. But I must draw this to a close, so I will discuss only one more person for whom Mexico served as muse.

CODA: Mexico as My Muse

When I was a little girl, my favorite television program was Howdy Doody. As a female viewer, my strongest identification was with Princess Summerfall Winterspring. (The “Indian” princess was portrayed by “white” actress Judy Tyler, an irony I did not understand until much later.) Throughout my childhood, I dressed as Summerfall Winterspring, wearing a short fringed dress, moccasins, beads and headband to birthday parties and Halloween. (Imagine how silly this looked on a little girl with curly red hair and freckles.) In college, the Indian princess look morphed seamlessly into Hippie attire: I wore fringed jacket, moccasins, love beads and headbands all over again.When I decided to go to graduate school in art history, I specialized in pre-Columbian and Native American art. I traveled repeatedly to Mexico, doing research in Mexico City and Oaxaca and visiting every major pre-Columbian site. I loved the people. I loved the food and became addicted to really hot chiles. I was seduced by the raw power of Aztec sculpture, recognizing the truth of the fierce feminine in Coatlicue. I was enraptured by the sheer beauty and grace of Palenque and the magnificence of Monte Alban. I was fascinated by the elegance of Mayan relief carvings and the precision of Mixtec jewelry. I collected folk art, especially wooden dance masks and traditional women’s clothing. When I began teaching, I wore Mixtec or Maya huipiles over jeans, hanging Zapotec earrings in the holes I pierced myself.

It wasn’t until I moved to California and found myself in a politically charged Chicano world that I began to understand the troubling racial politics of a white woman wearing indigenous attire. I stopped wearing huipiles and, eventually, I stopped teaching Native American and pre-Columbian art history. It no longer felt “right” to be a white person who was explaining—and thereby controlling the knowledge of—other cultures. Once I read Craig Owens’ “The Indignity of Speaking for Others,” I understood why. (Owens’ seminal essay is included in his Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power and Culture, 1992.) When I read about what is called Primitivism, especially as it applies to artists like Paul Gauguin, I realized that in my Summerfall Winterspring and hippie days, I had been something of a Primitivist, someone who turns away from her own culture to find answers in the Other.

I do not mean to say that my attraction to Mexico can be reduced completely to Primitivism. The clash of Mexico and U.S. cultures fueled my intellectual life. When I studied Mexican and Native American societies in graduate school, I learned about culture change and cultural difference. (I got my Ph.D. at the University of New Mexico—the perfect place for such studies.) Writing about Mexico led me to explore not only Said and Owens, but also writers as varied as Structuralist anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss and Phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty.

My journey through Mexico has been a journey from consumption to critical thinking. Just as Mexico turned Edward Weston into a sharp-focus photographer, Josef Albers into an abstract painter and June Wayne into a Social Realist, it changed me from an art historian trained in stylistic analysis to an eclectic Postmodernist. (And I’m still addicted to chiles.)

-

Catherine Opie

Catherine Opie enunciates the intentions and ideas behind her current body of 2012-2013 works with the first two images the viewer encounters—one a portrait, the other an abstracted landscape that could loosely be described as meditative.

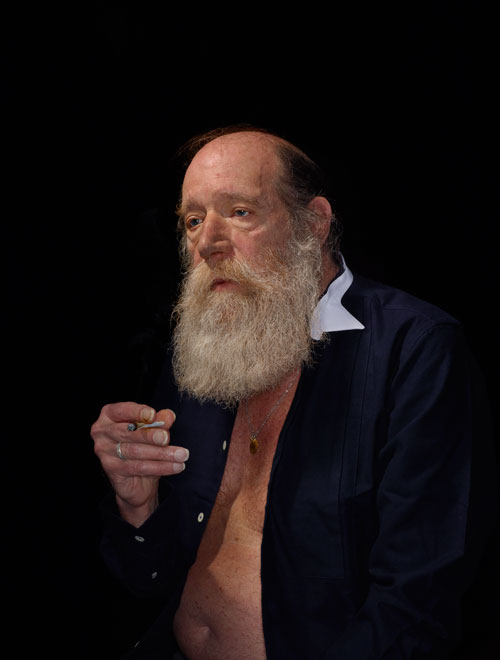

Lawrence (the conceptual artist, Lawrence Weiner), shining bald pate and frosty beard, open white-collared black shirt eliding seamlessly into the black backdrop, holding a cigarette, in slightly sheepish three-quarter view, receives our gaze with seeming resignation. Alongside it, what from the gallery doors might resemble a cluster of stars, a dazzle of light bounces off snowflakes falling on a darkened field, a stand of snow-dusted trees just barely limned in the middle ground. Light out of darkness.

Opie’s work implicitly addresses the cultural criteria for identification and identity as a function of place and, also, time. She hasn’t decontextualized her subjects here, so much as circumscribed their temporal actuality using disparate photographic means—in the portraits, closing in tightly on her subjects, isolating them in shadow and a dark surround; in the landscapes, opening the aperture and slowing or lengthening the exposure to sustain the moment. A deliberate ambiguity defines these blurred images. Our criteria for identification (or measure of geological and cosmic time) are called into question. Does the crest of a mountain ridge in one landscape (all of them untitled) loom any more prominently than a black tree dominating the foreground in another? The viewer’s notions of distance and proximity are inherently challenged.

Similarly, in the portraits, the emphasis on the temporal translates to gesture and attitude. In one of her largest photographs, Kate and Laura (the Mulleavy sisters, designers of the Rodarte fashion line), Laura, in long, ruffled white silk dress, kneels with a hand raised to Kate’s ear, as if whispering. Kate (black-clad) is seated, feet firmly planted, intently eyeing an embroidery circle through which she draws red thread seemingly into a red bloodstain. Portraits and landscapes alike connote realities both boldly stated and secretly whispered.

Another large portrait—Idexa (Stern, the tattoo artist)—presents an elaborately tattooed body frontally to the camera, but with head turned at an angle, eyes just slightly squinting: “Do I know you?” The photographs probe the notion of visual acquisition. We have the moment, and everything else stands outside it.

Opie draws on High Renaissance and Baroque conventions, not without an element of subversion, but her portraits are clearly ideations of her subjects. Her reverse three-quarter portrait of Jonathan (Franzen) is almost a literal instance of this—the spectacled silhouette just recognizable in shadow, with light catching the silvery highlights of his graying hair but falling principally on the book in his lap—Tolstoy’s War and Peace. (As serious as these portraits are, they are not without humor.)

To identify, specifically to name, is to fix in time. At their most transfixing, Opie’s photographs are about this imprint. An idealizing impulse manifests somewhere in the bleed from the conscious into the unconscious. But the magic inheres in plain view—although that view may be through murky depths.

-

Doug Aitken

Sonic Fountain, the centerpiece of Doug Aitken’s show (all works 2013) includes a large, round hole jack-hammered into the cement floor and filled with water. From above, a system of pipes with five spigots drips water into this small pool. The drops fall in programmed rhythms and are doubled with recorded water sounds. Each splash is synchronized with more synthetic and resonant recorded splashes, as if they were reverberating in a cave. Nearby sits a pile of excavated rubble.

The overall effect is perversely theatrical and yet formally awkward, with the five spigots arrayed like corners of a square and one in the center. The rhythm of the drops is predictably regular and yet irritatingly unmusical in a way that calls to mind someone practicing rudimentary beats on a drum. The synthetic sounds are both cheesy and redundant, yet manage to make the physical drops sound, by comparison, oddly banal (reminiscent of toilet splashes, sadly.) Likewise, the atmospherics make the laborious excavation seem relatively puny and prosaic. The whole thing cancels itself out. Oddly, it is also suspiciously similar to a more successful piece—Untitled (2011) from Jim Hodges’ 2011 show at Barbara Gladstone—in which Hodges made a nearly identical hole and rigged a disco ball to gradually lower itself from the ceiling until submerged.

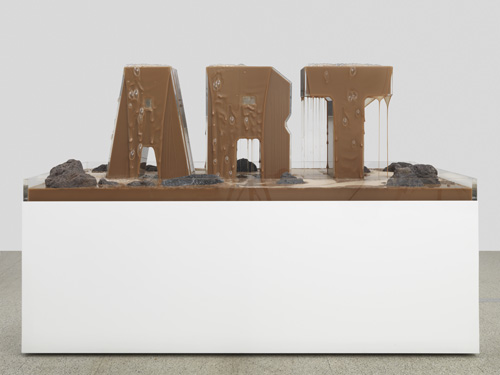

Aitken’s other sculpture here, Fountain (Earth Fountain), (2012) is blatantly derivative of a more famous work. In a large rectangular vitrine the letters “A-R-T”, built from Lucite, ooze smooth creamy mud resembling milk chocolate. It immediately recalls Robert Rauschenberg’s Mud Muse (1971)—itself a large rectangular vat filled with mud rigged to bubble and sputter like lava. The use of the word “ART” here merely underlines one obvious subtext of Rauschenberg’s piece: that something as ubiquitous and abject as mud could so effectively be corralled into the realm of art. This makes Aitken’s rather polished version more like CliffsNotes for a canonical work than anything else.

Here’s an even more tired trope: holes punched in gallery walls. While this device can be effective (if not subversive, as in the works of Gordon Matta-Clark) it’s become such a cliché that, at this point, Aitken’s version feels merely decorative. What’s worse, the holes are just-so: neatly cut through both layers of sheetrock with the interstitial space casually patched with cement and painted over. This creates the unconvincing impression of a rough but perfectly circular hole, over 8-feet wide, somehow spontaneously punched through a thick concrete wall. The large text pieces framed by these holes and situated a few feet behind them—Sunset (Black) and 100 YRS—are jokey, slick and elegant in ways that seems more like edgy design than art.

Another text piece, MORE (Shattered Pour), is made from faceted planes of mirrored glass spelling “MORE” with wet-looking broken mirrors coated in resin scattered in each letter’s convexity. It might seem custom-made to satirize art-market acquisitiveness except that its anodyne quality could just as easily play into it. Either way, it’s a nice looking object, but the viewer is left wanting, well… more. -

DOROTHEA TANNING

Dorothea Tanning was a painter, printmaker, sculptor, set designer, writer and poet who died last year at the age of 101. Best known for her enigmatic works of the 1940s and 1950s, which feature women and girls involved with strange animals and animated swaths of cloth or shreds of wallpaper, Tanning created a forceful combination of erotic danger and allure.

Birthday (1942) is a portrait of the artist as a young bacchante. Standing, bare-breasted, in a skirt composed of roots and tresses of hair before a succession of receding doorways, she is accompanied by a familiar winged quadruped, much like the comical demons that tormented Bosch’s saints. Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (A Little Night Music) (1943) features two young girls in tattered garments, clutching parts of a gigantic sunflower, fallen to the floor yet still alive; a series of closed doors gives way to one that is slightly ajar, admitting a wedge of yellow light. One girl listens, eyes closed, at one of the doors. The other, her face turned from us, regards the flower, while her long hair ripples upward, like tendrils or flames.

Tanning is also known as the wife of Dadaist/Surrealist Max Ernst. The personal and creative partnership lasted 30 years, though Tanning’s work was eclipsed in popularity by her older, more famous husband’s. When Ernst died in 1976, Tanning returned from France to New York, where she continued working for another 25 years, focusing, after a stroke, on the poetry and writing that would give her a late second creative career and further renown. Of the 30 works—oil paintings, sculptures, and drawing—included in “Unknown But Knowable States,” many have not been widely seen.

Tanning, whose tolerance for formal education had limits, was to an extent self-taught. A push-pull between attraction and repulsion powers the abstract images of tangled, submerged female figures, flying or falling that evolved in her “prism” or “insomnia” paintings from the mid-1950s. In Eclipse (1966) and Salut, Délire! (Hail, Delirium!) (1979), the traditional figurative art of Tiepolo, Rubens, Watteau and Rodin is reinterpreted through a combination of Cubist planes, Futurist simultaneity, Surrealist metamorphosis and Abstract Expressionist all-over patterning. This improbably successful eclectic mix is additionally leavened with Tanning’s semi-abstract eroticism—see Untitled (1965), with its echoes of Léonor Fini and Balthus and Notes for an Apocalypse (1978)—as well as her perversely humorous Peke-a-poo canine companions.

In Faith, Surrounded by Hope, Charity, and Other Monsters (1976), there’s an unmistakable similarity to Ernst’s grattage paintings of the same period, but Tanning’s vision is darker—more romantic and dramatic. A couple of sculptures, Traffic Sign (1970) and Etreinte (Restraint or Grip) (1969), exploit the abject faux coziness of fake fur. There’s an unusual note of pathos in Tanning’s drawing, Birthday, made in August, 1976, four months after her husband’s death; a woman, stunned, lies on a huge bed, almost buried herself, beneath a darkened sky.

-

Richard Jackson

Richard Jackson is a maniac with paint. His current retrospective is a testament to the gargantuan ambitions and massive amounts of energy he has displayed over a 40-plus-year career. The exhibition’s title, “Ain’t Painting a Pain,” is indicative of his commitment to the act of painting, although his real achievement as an artist is how he has consistently pushed the boundaries of the painting medium into installation, performance and sculpture, while still retaining a focus upon the act of painting itself.

A Jackson installation from 1980, “Big Ideas—1000 Pictures,” made an unforgettable impact when exhibited at Rosamund Felsen Gallery in Los Angeles with its 1000 painted canvases stacked from floor to ceiling. The radical nature of “the idea” as a way of dealing with painting was unprecedented—it could conceivably be compared to Pollock’s breakthrough drip paintings in its inventive re-thinking of the painting medium. The multi-colored, process-laden pattern, like bricks and mortar, was visually compelling as well. These works were intentionally ephemeral, but the OCMA show features a new similar work, “5050 Stacked Paintings” (2013), a monumental stack of dripping canvases creating a structure akin to terraces. One of the most formally captivating works in the show displays Jackson’s relation to both minimalist and process vocabularies.

The exhibition features work from every period of Jackson’s career, including several wall works from the period 1969–1988 made by pushing heavily paint-coated canvases across gallery walls, another terrific innovation of the painting process. Also included are many of the perspective drawings he has done over the years to plan his projects. In their visual resonance, the drawings are outstanding as works of art themselves and provide an intimate view into the playful musings that eventually resulted in huge projects requiring vast amounts of labor and materials.

“1000 Clocks” (1987-92), which was shown in “Helter Skelter” at MOCA in 1992, seems to mark the mid-point in Jackson’s career. The work he has done since then has been a departure, at least stylistically, from the painting installations of the 1970s and 80s. Jackson’s installations from the last two decades continue the exuberant energy of his earlier, more abstract projects, but the recent work is characterized by the use of representational sculptural forms. Much of his imagery is culled from art historical sources, as well as those reflecting more of a Pop, or Postmodern sensibility.

This work, while impressive, sometimes struggles to transcend spectacle—Bad Dog (2013), a giant dog peeing yellow paint on the museum is a hilarious jab at stuffy institutions, but lacks the complexity and innovation of the painting installations inside. However, “The Blue Room” (2011) is amongst the most successful of the newer installations. Based upon imagery from both Picasso and Duchamp, the painted installation pulsates with an inimitable chromatic energy.

What remains consistent throughout all the work is a love of the substance of paint itself—a highly-saturated, dripping, runny, viscous material. Jackson’s oeuvre wryly deconstructs art’s most enduring and dominant tradition.

-

Art Spiegelman

Fans of Art Spiegelman’s seminal graphic novel Maus can be forgiven for writing off Spiegelman as a one-hit wonder. After all, before producing the two volumes of the Holocaust memoir, which almost single-handedly turned the lowly comic book into a serious literary form, Spiegelman was a little-known creative consultant for the Topps Candy Company who moonlighted as a member of the Underground Comix movement. In the two decades since Maus, which won a special Pulitzer Prize in 1992, Spiegelman’s graphic novels have failed to live up to the promise of his breakout hit.

But a fascinating retrospective of Spiegelman’s work explodes this assumption, making a convincing case for Spiegelman as a brilliant visual polemicist and surprisingly avant-garde artist who for nearly half a century has twisted popular visual art forms to subversive ends.

“Co-Mix: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics and Scraps,” the first major exhibit of Spiegelman’s work since a 1992 show of Maus at the New York MOMA, begins with a series of gag trading cards he created for Topps, where Spiegelman worked for more than two decades. The Wacky Packages cards, which riff on popular consumer products (a box of Wheaties cereal is reimagined as “Weakies” and so on), and the later Garbage Pail Kids stickers, which satirize the cloying Cabbage Patch dolls, harness an antic Mad magazine–style comic sensibility to 1960s anti-consumerist political bent. The results are brilliant—sharp, funny miniature panels of visual invective that function as pocket-size Andy Warhol pop art paintings for nine-year-olds.

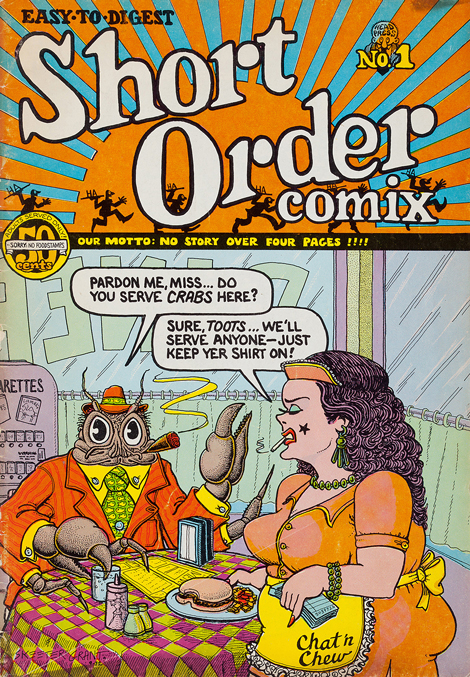

Art Spiegelman, “Short Order Comix no. 1. Cover,” 1973, © Art Spiegelman By displaying the bubblegum cards alongside the Underground Comix Spiegelman was creating at the same time he was working for Topps, the exhibit shows how his early hippie comics informed his coyly subversive commercial work, and vice versa. More importantly, these early works demonstrate how Spiegelman digested all manner of popular visual art, from Mad magazine gag panels to superhero comics, and refashioned them to more openly political (and often more personal) ends. From there, as the “Co-Mix” show makes clear, it is but a short conceptual step to Maus, a memoir of Spiegelman’s parents’ survival of Nazi pogroms and of Auschwitz reimagined as a sort of high-art “Tom and Jerry” cartoon, with the Jews as mice and the Germans as cats.

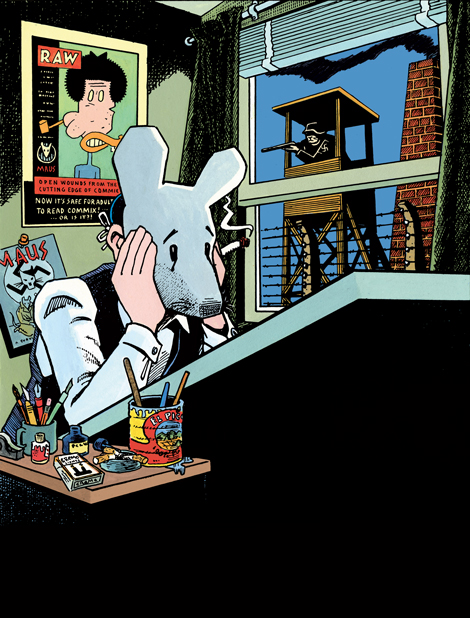

As is to be expected of any Spiegelman retrospective, Maus takes center stage in “Co-Mix,” with an entire room given over to the two-volume graphic novel that is sure to be Spiegelman’s most lasting work. The exhibit, designed in part by the artist himself, displays every page from Maus, along with dozens of sketches and preparatory drawings. The effect is grand, and also a bit demanding, since all but a few of the drawings are presented at their original size, forcing the viewer to stand inches from the wall and read the book panel by panel.

More successful, and in some ways more illuminating to those already familiar with Maus, are the rooms devoted to Spiegelman’s later work, especially his New Yorker magazine covers. The most visually arresting of these is the iconic black-on-black “Ground Zero,” depicting the missing Twin Towers, published weeks after the 9/11 attacks. Just as startling, though, is “Valentine’s Day,” showing a Hasidic Jewish man kissing a black woman, published in 1993 while the city was still recovering from the Crown Heights riots, three days of violence and looting that pitted Brooklyn’s Orthodox Jews against their African-American neighbors.

As with the Topps trading cards, the power of these images flows as much from their context as from their visual imagery. The Wacky Packages were not made to be displayed in a museum gallery but in the supermarkets where the products that the cards parodied were sold. To adult sensibilities, the sight gags and puns may sound like groaners, but to a nine-year-old boy shopping with his mom in 1974, Spiegelman’s cards depicting “Crust” toothpaste and “Jail-O” functioned as a critique of the very consumer culture into which the kid was being indoctrinated.

Art Spiegelman

Self Portrait with Maus Mask, 1989, Courtesy of the ArtistThe New Yorker covers carry this cultural critique into more sophisticated, racially fraught terrain. In New York City, the New Yorker is the voice of the Upper West Side liberal establishment, which had recoiled at the racial violence out in distant Brooklyn, so Spiegelman’s Valentine’s Day cover, with its deliberately shocking depiction of interracial love, served as a provocation to white liberals, saying in effect, “You think they’re racist—what about you?”

Some of the subversive flavor of these images is inevitably lost when they appear on museum walls, but the thoughtful layout of the exhibit, along with informative wall text in each gallery, help the viewer understand the original context. And in the end, Spiegelman’s work, visually rich, politically radical, equally at home with the profundities of history and low-minded crotch shots, speaks for itself.

-

FIELD REPORT: WANAS

“The artist comes first,” says Marika Wachtmeister, referring to the core philosophy of Wanås, one of the most remarkable contemporary art venues in the world, which she founded in 1987. Located in southern Sweden, Wanås is unlike anywhere else, offering a glorious combination of contemporary art and nature with a little history thrown in. In addition to contemporary art, the bucolic estate boasts a magnificent castle—originally built as a medieval fortification—beautiful parkland and some of the most interesting agrarian structures I have ever seen: enormous barns with brick, stone and stucco facades, now converted into exhibition spaces. With over 1,000 cows in residence, keeping company in a pasture with Maya Lin’s Eleven Minute Line (2004), Wanås is also one of the largest organic dairy farms in Northern Europe.

Wachtmeister spent her high school years in New York City, where she was captivated by the vibrant art scene. Seeing Niki de Saint-Phalle and Jean Tinguely’s The Fantastic Paradise (1968), an outdoor installation in Central Park’s Sheep Meadow, was a seminal experience, planting a seed from which Wanås has clearly grown. A dyed-in-the-wool feminist, Wachtmeister did not pursue art when she returned to Sweden for university, choosing instead a profession (law) that would ensure independence.

Wachtmeister’s transition from law to art occurred after her family moved to sleepy Knislinge in the 1980s to help run her husband’s family estate. Though Wanås has been a professionally administered foundation since 1996, it started quite casually. The first year, Wachtmeister, inspired by two outdoor sculpture shows she had recently seen, invited 25 artists to exhibit works on the estate, and it went from there.As word spread within the insular art world about the nurturing and supportive environment of Wanås, it began to attract more renowned artists. Fast forward 25 years and you have the highly acclaimed arts organization Wanås has become. Aside from the enormous satisfaction of creating it, Wachtmeister also discovered a pursuit that combined her love of art and New York, which she visited regularly searching for artists.

Early on, Wachtmeister made the decision to focus on site-specific works that centered on the remarkable setting that is Wanås. “Wanås made artists brave,” she explains, “inspiring them to try things they might not have done before.” The original work was, for the most part, playful, ephemeral. Now it’s more serious and enduring. Of the 53 pieces currently in the collection, only Bernard Kirschenbaum’s minimalist Cable Arc survives from the first year.

Wachtmeister has recently passed the baton to Co-Directors Elisabeth Millqvist and Mattias Givell, who come from Stockholm’s distinguished contemporary art space, Magazine 3. Wanås will continue its current format of presenting two new artists each year (plus a “Revisit” artist—a returning artist from the collection), but it’s redirecting its focus to include more Third World voices. Millqvist is eager to see how artists from nonwestern cultures and far-flung parts of the world interact with Wanås. She’s also committed to Wanås’ vital educational outreach programs.

Louise Bourgeois, Maman, 1999, at Wanås 2007, The Wanås Foundation, Sweden,

Photo: Anders NorrsellI was enchanted by Wanås. Most of the installations are situated within the fairytale forest, which not only means the aesthetic integrity of the estate is preserved, but you get to experience a wonderful scavenger hunt of discovery as you wander through the woods in search of artwork that is spread over 1.5 square miles (It takes about six hours). Visiting as the season was winding down, I had the park to myself and it was magical and, at times, quite mysterious.

There are many art stars in the collection, including Yoko Ono, Robert Wilson, Ann Hamilton, Janet Cardiff, Jenny Holzer, Marina Abramovic and Antony Gormley. Louise Bourgeois’ “Maman” spent a season there—and though she coveted it, Wachtmeister decided the $8 million price tag was better spent in other ways. A number of artists were new to me: Marianne Lindberg de Geer, Malin Holmberg, Esther Shalev-Gerz, Jacob Dahlgren—my favorites.

What is most compelling about Wanås is the way art and nature and art in nature are treated. Wanås manages to honor both the artwork and the natural beauty of its location. It strives for and achieves an intimate experience between viewer and artwork and also provides a most memorable one.

By following her passion and embracing the new and the challenging, Wachtmeister has done something amazing with what might have been an onerous family legacy. Nowadays, Wanås is more vibrant and relevant than ever with a reach that extends across international borders, contributing in numerous ways to the advancement of culture. -

MEXICO al MAXIMO

The Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach calls itself, “The only museum in the United States exclusively dedicated to modern and contemporary Latin American art.” Yet its permanent collection is comprised largely of works from Mexico, with exhibitions often featuring art from that country. Idurre Alonso, curator there since 2002, talks about the “aestheticism” of contemporary Mexican art that is on a par with that from the United States and Europe. She credits this in part to Mexico’s comprehensive support of the arts. “The country gives out so many grants that emerging artists are able to live largely on grant money.” She adds that the government supports most museums, freeing them to devote energy to exhibitions, while Mexican citizens are usually admitted for free. “On weekends, museums and galleries are filled with families of all classes,” she says, adding, “Art there is not just for the elite.” Mexico’s support for the arts goes back 100 years to when the government subsidized its murals, regarding them as tools for education about the country’s history.

Alonso grew up in the Basque country of Spain with art-loving parents and grandparents. As a child, she frequented the local Bilbao museum and later the Guggenheim Museum there. While in college, she interned at MOLAA, developing a passion for Latin American art, and began working there after graduation. Since starting there, Alonso and the staff have been working toward connecting Latin American art with that of disparate locales, creating exhibitions with a more universal approach.

Dream Addictive, Solar Sound/Sonido solar, 2010, at MOLAA Alonso curated “Descartes” in 2010, showing work by Mexican artists who emerged into the Tijuana-based international art scene in the late 1990s. The Collaborative Gallery (jointly owned by MOLAA and Long Beach) exhibition featured “readymade” objects, exploring Mexican-related issues such as immigration, exploitation, consumerism and the environment. UCLA graduate Camilo Ontiveros’ Deportables/Mattresses, constructed from discarded mattresses, bound in rope and hung on the wall, and his Restrained (both, 2008), a beat-up washing machine on its side, depict the selling of cast-off objects in Mexico at outrageous prices. Solar Garden (2010) by Dream Addictive (the art collective, Leslie García and Carmen González) employs recycled electronic and solar-powered equipment, demonstrating that even solar material is discarded in our throwaway world. Jaime Ruiz-Otis’ Untitled (2010) is a landscape made from discarded industrial stickers and labels.

At our meeting, Alonso pulls out three MOLAA exhibition catalogs, providing historical reference for contemporary Mexican art. “Mex/L.A. ‘Mexican’ Modernism(s) in Los Angeles, 1930–1985” explored the relationship between artists and supporters on both sides of the border. The show included descriptions of Los Angeles murals by José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros and graffiti art by Chaz Bojorquez. There was also Disney animation inspired by Mexican culture, including The Three Caballeros (1945) starring Donald Duck. Pieces in this show, largely from the “Mexican modernism” era, often incorporate influences from primitive and unschooled artists—a trend persisting in Mexican art today.

The museum’s 2011 “Mexico: Expected/Unexpected,” with modern and contemporary paintings, photography, installation, video art and sculpture from Latin America, Europe and the United States, included works by Mexicans Carlos Amorales and Manuel Álvarez Bravo, and by Americans Ana Mendieta (born in Cuba) and contemporary artist Ed Ruscha. Amorales’ Panorama (2007), large collage drawings with stark images of birds, apes, humans and hybrids depicts violence in humans and animals. These were hung near Mendieta’s equally dark On Giving Life (1975), a photograph of the artist lying naked in the grass atop a skeleton.

“Changing the Focus: Latin American Photography 1990–2005” (2010), curated by Alonso, demonstrated how “Latin American photography took its rightful place within the international contemporary art scene,” as the catalog explains. It explored current social, political and economic perspectives of Latin American photographic art. Death by Tupperware (2005) by Daniela Edburg from Mexico, of a woman in her kitchen being strangled by a monster arising from a plastic container surrounded by American convenience foods, is a metaphor for the perceived strangulation of Mexico by the U.S. and its processed products. Two elegant images by Mexican Daniela Rossell, from her 2002 “Rich and Famous” series, portray wealthy Mexican women in palatial estates, both homes lavishly appointed with Latin and European décor. These photos, referencing iconic Renaissance paintings, provide a window into this (nearly oligarchic) country’s embrace of styles and cultures far beyond its borders.

“This region’s art is as relevant today as that in Europe and North America,” Alonso explains, adding, “In the 20th century alone, Latin American artists have worked in surrealism, social realism, abstraction, conceptualism and more.” With so many artists and movements to present, her goal is to continue to create significant exhibitions and catalogs—to foster worldwide understanding of Latin American and Mexican art.

-

JENNIFER REEVES

“Abstraction talks her head off. She has a lot to say.”

You might not hear her right away, but Jennifer Wynne Reeves does. “I tune out or listen,” she adds, in the penciled text within a painting, “rattled by her noisy silence.” She is also silently talking back. She could be abstracting away from reality, building life on abstraction, or discovering her inner child.

Reeves sticks her text on three paintings, all from late 2012 and 2013, as if cut from a school notebook by a precocious learner. Each fragment shares a wooden frame with shards of acrylic or molding paste, but nothing within the frame, least of all abstraction. In due course, with Untitled Collage, one may spot loose grids of soft colors, as with Paul Klee, but with more shards sticking off the edges. They could pass for shattered porcelain from her morning coffee or the leavings of a brush wiped clean, on the way to painting something else. And mostly that something else is telling stories. Abstraction has the choice of tuning out or listening.

Maybe Reeves has not really saved her notebook all these years (and her texts often appear as Facebook posts as well, perhaps to rethink physical drawing as part of an ongoing virtual project). Still, a drawing from age nine does greet visitors on the way in—alongside a few messy sculptures somewhere between figurines, abstraction, and child’s play. She calls the show “The Worms in the Wall at Mondrian’s House,” as if Piet Mondrian had grown up on it. And the same gallery has had echoes of outsider art and personal confessions from Amy Wilson.

Yet Reeves is not as innocent as she may appear. Her gouache on paper has its realism, like the gray streaks of a damp sky or the scumbled vegetation of an open field. It also has somber dreams. The sailboat in Grace Note passes beneath a rainbow all but landing on its deck, and her characters are often at sea. A traveler in Far Away but Not Far Apart crosses a bridge in low light, behind fencing not at all comforting in its whiteness. A prancing horse in Horse Comforter does not escape its tether, and a wolf howls at a star. In I See Two Birds a shotgun brings down a bird, although another bird flies above, while a robin perches comfortably on a power line.

Actual wire, for her, is part of abstraction’s sign language. She draws with it and puns on it, as with the tense coils of those utility poles. Maybe she exaggerates the coiling and its looseness, but electricity works that way, and so does the loneliness of power lines beside a road.

When it comes to abstraction, many artists today feel a certain ambivalence. Like Amy Sillman, Sara VanDerBeek, and so many others, they are looking for a space between abstraction and realism. In the end, Reeves and abstraction reach an accommodation—”a perfectly unexpected Boogie Woogie.” Still, these are first and foremost her own stories, far from Mondrian’s Broadway.

-

Editor’s Letter

Not so long ago on a return flight to LA, I was sitting next to a young Boston couple who had never been to the West Coast before. I asked them what the first thing they wanted to do was when they landed. They said they wanted to eat at Del Taco. I tried to hide my horror and politely suggested that if they noticed any of the numerous taco trucks parked on the streets of our fair city, to please try those tacos as well. “It’s the closest thing you’ll get to Mexico without going to Mexico,” I told them. That didn’t seem to impress them at all. They much preferred their Del Taco wet dream while be-bopping to their iTunes.

Not so long ago on a return flight to LA, I was sitting next to a young Boston couple who had never been to the West Coast before. I asked them what the first thing they wanted to do was when they landed. They said they wanted to eat at Del Taco. I tried to hide my horror and politely suggested that if they noticed any of the numerous taco trucks parked on the streets of our fair city, to please try those tacos as well. “It’s the closest thing you’ll get to Mexico without going to Mexico,” I told them. That didn’t seem to impress them at all. They much preferred their Del Taco wet dream while be-bopping to their iTunes.I can’t claim to be an authority on Mexican culture, but living in Los Angeles does lend some street cred. Growing up in Missouri, you couldn’t get any further from Latin culture. My closest encounter were the tacos my Italian-American mom made with ground beef spiced with Lawry’s taco seasoning and topped with shredded cheddar cheese in crunchy taco shells, still warm from the oven. That Taco Bell sensibility kills me now, having lived in Southern California for over two decades.Maybe I shouldn’t be so hard on the Boston teeny-boppers.

Mexican art has been on my mind for some time. The prospect of devoting an issue to it was met with enthusiasm at an editorial meeting a while ago, but put on the back burner. Now it’s resurfaced, and in this issue my contributors more than make up for my lack of experience south of the border. Some of our writers have collaborated with the artists profiled here or have shown their own work in Mexico. Some have curated contemporary Latin art, or just championed an artist’s work. We have chosen to focus only on artists who are Mexican by birth, who are now living and working either in Mexico or the U.S.

The result is a rich array of our contributors sharing their Latin passion with Artillery. Chris Kraus delights us with her trip to Mexicali, cavorting with a neo-muralist. Betty Ann Brown recalls her youthful fascination with Mexico, right down to her addiction to hot chilies. Amy Pederson deconstructs rebel artist Joaquin Segura, and Tyler Hubby checks in with Yoshua Okón of Mexico City’s art space SOMA.

I wanted to do this Mexico issue because I felt ignorant about the art being made there. There’s so much happening in the Mexican and Latin American art scene—more art fairs, more collectors, more artists. And it so happens that the Getty is launching another segment of their PST program, this time calling it LA/LA, short for Los Angeles and Latin America. Maybe the timing is just right.

But before I sign off, I can’t end without drawing your attention to our newly designed website: artillerymag.com. Check it out. We’re working on adding all of your past favorite columns, articles and reviews, all archived, and preserving seven years of Artillery. We’ll be adding content to it throughout the summer. Something to keep you busy and out of the sun!

-

PROFILES: JOAQUIN SEGURA

Throughout his 1982 book All That is Solid Melts Into Air, Marshall Berman returns over and over to a single passage from Marx’s Communist Manifesto:

All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and men at last are forced to face….the real conditions of their lives and their relations with their fellow men.

Published very shortly after the death of his son Marc at the age of 5, this collection of essays is ostensibly dedicated to a parsing of Marxism and its various legacies and applications. Yet in many ways Marx is an oblique figure here, a character through whom the melancholic narrative of loss that defines the Modernist condition is performed. Berman’s accounts of Marx’s theories and their operations in the world are in part autobiographical, and include indirect accounts of Berman’s own sadness, his loss, his feelings of alienation and homelessness, of being unmoored and unanchored in a melting world. Some thirty years later, we still exist in this eschatological place of desublimation. Superficially at least, everything has changed, but underneath nothing is different when it comes to a shared feeling of permanent malaise.

Segura shares the dread Berman articulates in his essays, and perhaps also responds to it in an indirectly autobiographical fashion. In a recent interview with Thomas Jeppe, Segura noted, “I always have a sense that in Mexico, in Latin America, your context is escaping through your hands, you can barely grasp at it. You should approach it in this immediate and more effective way to make it mean something somehow.” I’m reminded here of a game played by children in science class in order to test their reflexes. One person holds an object a few inches above another person’s closed hand. The first asks the second if they are ready. When they say ‘yes,’ the object is dropped. The second person almost never catches it. To grasp for one’s context, one’s placement in time and space, is to grasp at straws.

A few years after Berman wrote All That is Solid, Paul Virilio and Sylvere Lotringer published Pure War (1983), an extended conversation about the invisible global conflict between technology and humanity, and the collapse of the boundary between war and peace. Almost twenty years later, they reconsidered some of these same concerns in The Accident of Art (2005) and came to this conclusion: art is the casualty of war. In our present moment, the fear and paranoia of the 1980s seems hopelessly old fashioned, even romantic. The world was altered through the failure of classical war and the disintegration of the nation-state. The concept of cold warfare through military deterrence is a laughable specter of simpler times, and all war today is transpolitical, asymmetrical and utterly terrifying. Art now, Virilio tells us, is terrorist and terrorized. Beginning with trench warfare as reflected in the horrifying images of Otto Dix, the Frankenstein’s monster of Cubism created by Braque and Picasso from the fragmented corporeality of World War I, and so on and so forth, art is a distorted mirror for the causes and effects of social violence. Attempts to camouflage this reality can only occur on the surface, with the blood of these deep lacerations welling up beneath the paint. Efforts to ignore or repress these facts result only in disfigurations that draw even more attention to this brutality.

In The Accident of Art, Lotringer tells an anecdote about a WWII memorial built in Vienna in the 1950s. While celebrating the military combatants involved in the conflict, the installation neglected to make any mention of the role of Jews during wartime. In the 1980s, this oversight was rectified by the addition of a bronze figure of a stooped old Jew pushing a broom. This statue was of a proportion and in a location that tourists began using it as a place to sit and rest. The Viennese, in an attempt to prevent this behavior, surrounded the Jew with barbed wire, seemingly without giving any thought to the historical or aesthetic implications of this addition. “To me,” Lotringer commented, “this desperate attempt to repair the desecration by committing a new one was the best memorial to what had been done to the Jews and they should have kept the barbed wire right there, possibly unroll it around the city of Vienna while they were at it.” I laughed when I read this passage and thought to myself, that is something Joaquin Segura would do.

Joaquin Segura

Gringo Loco, 2009

Courtesy of Arena México Arte ContemporáneoIn 2009, Segura was famously the victim of censorship when the Guadalajara City Council refused to grant permission for the installation of a previously authorized work in the Parque Mirador Independencia. Modeled after the Welcome To Fabulous Las Vegas sign on the outskirts of that city, this sign proclaimed “Fuck off you chili-eatin’ gringo loco up your ass!” To me, the real mystery is not that this sign was censored during its installation, but that it was approved in the first place.

Segura’s natural habitat is what Hakim Bey called the Temporary Autonomous Zone, a punk rock anarchism littered with empty beer bottles and full ashtrays. In the TAZ, the permanent terrorism warned of by Lotringer and Virilio has been leavened by poetry, the hamstrung artist has remade himself as a saboteur of the first order and art as a criminal act.

I first met Joaquin in Los Angeles in 2006 when he came to do an artist’s residency through the organization Outpost for Contemporary Art, along with Renato Garza and another young artist from Mexico City. They showed at the storefront Gallery 727, located in a framing shop in a downtown neighborhood with a large Salvadorean community. Garza made fake rubber flayed skins of Mara Salvatrucha gang members and displayed them prominently on the floor of the gallery. Segura produced “ethnically correct” California license plates that read beaner, brownie, and wetback, and distributed t-shirts illustrated with instructions on how to make a suicide bomb. The third artist gave a poorly conceived and executed lecture about the film The Matrix and the art critic Cuauhtemoc Medina.

After a heated argument with the third artist about the quality and quantity of his work, Renato left the apartment and Joaquin went to bed, but was soon awoken by a full-blown physical attack. The bad lecturer smashed Segura’s head against the concrete floor repeatedly, and after returning to Mexico he was diagnosed with serious neurological trauma and swelling of the brain. He could easily have died from cerebral hemorrhaging and become another foreign corpse in the LA morgue, not so different from the dead gangsters Renato made while they were here.

In her 2008 essay on contemporary Mexican art titled “Pull the Trigger,” Gabriela Jauregui describes Segura as a guerilla artist, possibly even a terrorist one. But, she warns, his band of rebelliousness can easily be recouped by the cultural establishment, acting as an inoculation against the infection of real social and aesthetic change. Jauregui posits artistic self-referentiality as Segura’s response, and points to Los dos Gabrieles (2005), a parodic reimagining of Frida Kahlo’s doubled self-portrait in which her visage is replaced by two Gabriel Orozcos.

An interesting result of this adversarial strategy has been its recent détournement. After leaving the opening of an exhibition of video in DF in early October of last year, we returned to the artist’s car to find that it had been vandalized. A series of bumper stickers (I heart bumper stickers [2004]) Segura had printed as part of another recent exhibition at the Sala de Arte Publico Siqueiros had been unpeeled and stuck all over the car, with the paper backings stuck under the windshield wiper in a stack. His Renault was now covered with the slogans: “I heart Goebbels,” “I heart Gaddafi,” “I heart Pol Pot,” etc. Joaquin was really angry. He could only guess that whoever had done it had read on his Facebook wall that he was in town and would be attending the opening. I wondered if it wasn’t one of the younger students at SOMA who seemed to idolize him so much, imitating his look, his style and his art. No one can be a permanent teenager, just as no one can be a permanent revolutionary. At a certain point, and with any measure of success, we cross the border demarcating outsiders from the establishment. Beyond this limit, an army of Oedipal minions wait to attack.

Joaquin Segura,

I Heart, 2004-2011

Courtesy of Arena México Arte Contemporáneo

Photo: Ernesto RosasOn a recent trip to Guadalajara, Segura asked me if I could bring down some books that he wanted to buy online. When the box from Amazon.com arrived, I was embarrassed to find copies of The Unabomber Manifesto, Mao’s little red book, and Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Of course, my bag was searched by customs official in the airport. I felt like a complete asshole, and it occurred to me that I might have been unwittingly drafted to participate in some kind of art performance. Joaquin assured me that was not the case, but a trace of doubt remains. When we got to the apartment, the books were put on the table in a stack and started to accumulate ashtrays, papers, other books, and sticky rings from beer cans. Next to my library books and the research materials that I had brought from my own collection, the new books started to take on a plastic hollowness, and the weight and force of their contents in regards to politics, violence, and modern history became lesser and lesser until they started to disappear. The books became homogenous sculptures, and the information contained on and in them was almost completely evacuated. To me, this was a melancholic loss.

A similar emptying out can be detected in Segura’s engagement with identity on both a personal and collective level. To Jeppe, Segura made the claim: “I absolutely despise the idea of national identity and I don’t really believe in the idea of country, and most of the work I produce just mocks this idea of Latin American art, or Mexican contemporary art, which I think is absurd. It’s just an accidental geographical event that I was born and work here.” Race is a construct, nationalism is a fiction, and “Mexican” is only a random attribute. This is a clever feint, but one that does not eliminate the problem of overdetermination. Denial and repression always leave a trace, and from Schelling by way of Freud, “everything is unheimlich that ought to have remained secret and hidden but has come to light.” Nationalism is not neutral, and it bears within it the stratification of history, the presuppositions and biases of hundreds of years. An accident of birth may be just that, but nevertheless it results in certain facts.

The category of Latin America has a complicated relationship with historical bodies of all sorts. Colonialism is an indelible weight, but this region is characterized by a special, doubled modernism that can be strategically attacked. Cannibalism in the New World, whether real or imagined, was one of the central moral rationales for colonialism, and it is no accident that the etymological and sociological origins of the cannibal coincide with the discovery of the Americas. I hereby propose Joaquin Segura’s work as inherently anthropophagous. According to Romanian philosopher Catalin Avramescu, the cannibal is a scholarly creature, a thought experiment that interrogates identity on the verge of collapse, posits an ethics without morals, and instills anarchy into the social order. In the West, “the cannibal is the messenger of disorder, the proof that moral chaos has descended upon us, human nature at its worst, the unusable atom of an impossible social order.”

Recently, Segura told gallerist Brett Schultz:

The fact that I live and work in Mexico is a completely random

geographical and temporal factor, which of course affects what

I think and what I do, but I’ve chosen not to be limited by this

specific circumstance. In the past, while working abroad, I’ve

taken advantage of this preconception of Mexico—to be more

exact, pretty much all of Latin America—as one of the last

barbaric bastions of western civilization.Segura plays the role of the anthropological savage, employing the Mexican label as a temporary and expedient strategy for making art and fucking with culture.

Individuals who repeatedly transgress the socially policed standards of cultural identity are inherently threatening to the authenticity and power of this entire ideological edifice. But within these transgressions, as Jauregui noted, the potential for assimilation and neutralization is ever present. Possibly Segura’s work indicates a solipsistic miring in the practice of overdetermination from without. The perception of Mexicanness he plays with lines up with the most racist fantasies of gringo outsiders, but a feeling of complicitness often outweighs any evidence of critique. Beyond categorical rejection, what Joaquin himself thinks of Mexico and Mexicans remains largely a secret. Certainly, it is a fraught relationship.

Thomas Jeppe writes, “Segura’s themes are enlivened by the cultural-political environment of Mexico, so far from the conditions that generate the contemplative Conceptualism of Europe and the United States.” While perhaps true on its face, this contemplation leads to complacency, and often results in the widespread production of art of the most banal and mediocre sort. This cultural production is propped up by the sorts of governmental subsidies that protect the commodity trade for such other things as butter and wine. Certainly, the booming but largely conservative art market has long supported this work. Against this, I propose Virilio’s theory of the accident as a corrective. The accident is relative, unexpected, and necessary; the invention of air travel is the invention of the plane crash, after all.

The modern condition is perhaps writ large within the present context of Latin America. A permanent state of crisis, the institutionalization of revolution, a conglomeration of failed states, each of which is crumbling into pieces. This uncertainty and instability can be considered as a boon to art making, if as Segura suggests, “you learn to function within a context that forces you to do more with less. To potentialize what you have.”

Joaquin Segura

Homemade (Napalm #1), 2010

Courtesy of Arena México Arte ContemporáneoFacts about a Mexican context include the hyperviolent climate of everyday life, and the question of class that affects contemporary artistic production and reception on every level. The normalization of violence produces a permanent state of semi-fearfulness accompanied by numbness. In this light, it seems difficult to get upset by some of Segura’s more provocative images, since they cannot hope to compete with the theater of cruelty performed daily in the world. The intent of the artist in relation to his audience (indeed, his intended audience) can be called into question. But it seems unfair that there can be any added or specific regard for reception that Mexican artists must take into account, some extra burden from which European or American artists are exempt. As Hakim Bey asserts, “…even the truest secret becomes yet another mask.”

Almost every review of Segura’s work refers to him as an enfant terrible, but I think this is a title he has outgrown. His rage is cut with melancholy and deepened by maturity, but I wonder if this kind of practice is sustainable in the long term.

I didn’t understand the nature of subtlety before. I used to think

that you needed to be loud and manifest anger and unconformity

in the most aggressive manner possible. Then I finally realized that

you can actually permeate and rarify a battleground—because after

all, this is low intensity war—if you actually aim at silently building

up the contradictions and making the symbolic value of ideas and

acts clash within themselves. Or perhaps it is that I am just getting

old. I guess I used to be an angry kid until recently.An aesthetic of provocation is perhaps the strongest continuous legacy of the historical avant garde. Segura states: “I’m trying to formulate some sort of poetics of disaster.” I believe this to be true and entirely in keeping with the most radical and utopian modern traditions. To summarize Adorno, the mark of truth and freedom can only be found in art of all stripes, or, to quote Berman directly, “to give up the quest for transcendence is to erect a halo around one’s own stagnation and resignation.”

To paraphrase revolutionary filmmaker Melvin van Peebles, Segura may be an asshole, but he’s not stupid. Segura’s art is like fireworks: a weapon, but one invented to cause aesthetic shock, and not intended for use in war.

If I were to kiss you here they’d call it an act of terrorism—so let’s

take our pistols to bed and wake up the city at midnight like

drunken bandits celebrating with a fusillade, the message of the

taste of chaos.–Los Angeles, February 2012

This article is an expanded version of our printed article.

Dr. Amy Marie Pederson is an Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Art History at Woodbury University in Burbank, CA. She is a co-curator of the MexiCali Biennial and was the curator of La Quebradora: Lucha Libre in Contemporary Mexican Art at the Mission Cultural Center for the Latino Arts in San Francisco (Summer 2012). Her research interests include poststructuralist theory and zombies.

-

PROFILES: Elina Chauvet

It was in 2009, while teaching art workshops in Ciudad Juárez, that artist Elina Chauvet became aware of the numbers of women and girls disappearing from the city’s streets. She was shocked by the many posters on phone poles and boards pleading for help locating missing women. Most were never to be seen again—probably victims of rape and murder. The authorities were putting practically no effort into tracking down the guilty parties. Those lives were not considered of value by those in power. Chauvet conceived of a project to draw global attention to this tragedy.

Zapatos Rojos (Red Shoes) was always intended, Chauvet explained, to be “a huge event, a social event.” We spoke in a friend’s sun-filled casa in Mazatlan’s historic district. Dark-haired Elina, attractive, mature yet youthful, has flashing eyes and a ready laugh. But her cheerful disposition veils a dead-serious commitment. Well aware that “so many activists on this subject were frequently intimidated, or killed,” the artist felt that engaging many people would not only spread her message more widely, but “would also serve as protection.” Chauvet embarked on a grassroots campaign for justice, putting out the request through friends for donations of red shoes.

Each pair of shoes symbolizes a woman who vanished from the streets of Ciudad, red representing their spilled blood. Her first installation comprised 33 pairs of shoes, installed back on the very Juárez sidewalks where the women had been abducted; slingbacks, pumps, boots and even children’s Mary Janes, suggesting shoes the women and girls might, in fact, have worn, lined up as though in a procession bearing witness to the crimes.

Chauvet, no stranger to personal tragedy, lost her sister 22 years ago—murdered by a husband never prosecuted for the crime. While Elina had known “from the day I was born that I was an artist,” her studies were in the field of architecture, right in Ciudad Juárez. It was after the death of her sister that she returned to her fine art work, finding in it a way to work through her pain. Her early works were influenced by Picasso, Magritte and Kahlo. Expressionistic and personal imagery combining women in shawls, hearts, birds, flowers and angels filled her vibrant canvases. These garnered some recognition, in the U.S. as well as Mexico, but it was her fierce commitment to her installation work that has attracted international attention.

Elina Chauvet and shoes, photo by Luis Brito. The Zapatos Rojos project has taken on a life of its own. Already taken to six locations in Mexico, Chauvet installed the Zapatos Rojos last July in front of the Mexican consulate in El Paso, Texas. This drew the attention of women worldwide—and the international human rights community. The project was selected in Italy to represent the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, and her work has, in conjunction, been installed in Milan, Turin, Genoa and Lecce; the artist will travel to Bergamo, Italy in May for its installation events there.

While so many have embraced Zapatos Rojos, including families of the missing women—mothers of the victims installed the piece in Ciudad Juárez last December—the government of Chihuahua State continues to turn a blind eye. It is the unwillingness, if not complicity, of the government that has allowed this appalling situation to exist. Chauvet remains optimistic, “the minds of women in Mexico are changing. They are not accepting the violence anymore, and are talking about it. Before they did not talk about this. Maybe this is the first step.”

-

PROFILES: Sergio Bromberg

In the 20th century there has long been a long tradition of artists extending their visions beyond the studio walls to encompass a wider range of ideas and modes of thinking, wherein artists like Wallace Berman with his magazine Semina in the ’60s, or much later in the mid-’90s, Daniel Joseph Martinez with the nonprofit space Deep River, could extend their minds in idiosyncratic ways toward a complex, cohesive process of understanding. Sergio Bromberg is an artist who runs a gallery in the midtown La Cienega Arts district.This artist/gallerist combination can make for some of the most visually compelling art, most of which derives from an intensely realized rigorous investigative process.

Bromberg was born in Mexico City and originally moved to Los Angeles to attend graduate school at Otis. Receiving his MFA in 2011, he opened his not-for-profit gallery Venice 6114. The nondescript space could well be mistaken for a body shop as it sits smack amid a row of them. No specific signage distinguishes from its milieu, yet that choice is very much in keeping with Bromberg’s aesthetic approach—to keep things simple and pure; this is indeed reflected in the kind of art he shows, work that sometimes takes months to install and requires much planning and discussions with the artists. Bromberg describes it as “building an essential conversation that goes on for some time.” This process is what interests Bromberg most and derives from his ongoing relationship with the art being made in Mexico City today, work that is systemic and organic and derives from an essential and undeniable need to make it, as he explained, “In Mexico, being an artist is a fight, a risk. It’s not like it is here. It’s not a choice, but something you are called to do. Over there we say you ‘have to get out to get in’ meaning it’s very difficult to make it as an artist and many times artists have to leave, make their mark somewhere else and then come back again.”

Bromberg has shown his own work most recently in Yautepac, a Mexico City district, and again the work is process driven and could take a long time to realize. “What I like most about contemporary art being made here in LA versus in Mexico is how fluid and fertile they both are, kind of like the Wild West all over again. Anything goes and this same adventurous feeling exists in Mexico as well. It’s exploding with energy and ideas.”

Ideas are vital to Bromberg, who looks for art that can only exist if activated by the viewer, work that has a social component—based on a specific project. “The artist comes to me with a certain idea and I think of it as my having the right amount of steroids to grow that idea into something really powerful.”

-

PROFILES: Marycarmen Arroyo Macias

Meeting Marycarmen Arroyo Macias in MexiCali was a fortuitous event; she lent me her camera in a pinch to photograph potential performance locations for the MexiCali Biennial 13, in which we were both included. When I asked about her work for the show, she told me the museum was concerned about her plan to install raw meat in the gallery, for fear it would attract rodents and insects.

It wasn’t until I encountered Tomad y Comed… (2012) at the Vincent Price Art Museum (a pig blood version, oxidizing into a rusty brown) that the embodied impact of Arroyo Macias’ materials hit me. Her symbolic and literal pound of flesh called up an array of political, gendered, economic, religious and social problems around Mexican identity. Her use of language is a consistent theme, and the selection of words from a deeply ingrained Catholic ritual further complicated the installation. “I associate cannibalism with religion here in Mexico,” she said. “We have a deeply held belief that we must sacrifice our happiness, our lives, our loves—to help others, especially our families. I don’t agree with this idea of sacrifice, which is more powerful and constant with women; but other kinds of sacrifice happen for men, and often through religion, the problem of Catholicism.”Arroyo Macias’ family resides in Tijuana, Puebla, San Diego and Mexicali; she travels between these regions and addresses their disparities in her projects. For the Puebla Biennial she created Diccionario Spanglish, a flag of red and green “words in our common language.” Each word or phrase has various degrees of usage and familiarity depending on the region, from Frontera to El Centro. By playing with their meanings, definitions and recognizability, Arroyo Macias also plays with the shifting identity of being Mexican and how that identity manifests through language.

Arroyo Macias connects strongly with painting as a medium; her most recent project takes the famous Magritte work Ce N’est Pas Une Pipe (“This is Not a Pipe”) as inspiration. Emergente is both an investigation and intervention exploring the economic and political impact of Mexico’s franeleros, or window washers, who congregate around the border and offer to wash the windshields of autos stuck in la linea. Arroyo Macias interviews these workers on whether their labor is designated “illegal,” and on their defamation by merchants who often suspect them of theft. She trades a fresh franela to the workers for their used dirty franela, and will sew the soiled cloths together into a large quilt-like piece, to be labeled with the crossed-out saying Esto no es un Trabajo (“This is Not a Work”). “This situation has been created from the conflicts around education, economies and immigration, political problems that come from this kind of labor. We need to accept that this work is happening out of necessity; the causes that create it are in control of the government,” explains Arroyo Macias. She intends to collaborate with Mexican video artist Karla Paulina Sanchez to document her exchanges with the franeleros and the conditions of her labor. “My first language was painting, “ she said, “but I ask for help and have contact with people in using media, although I like to use objects in my process… political and economic paradigms are a part of my work, continuously.”

-

PROFILES: Miguel Osuna

Miguel Osuna’s grandly decaying storefront studio at 4th and Spring streets is a workshop, a think tank, a popular spot on the monthly downtown art walk and a place where skateboarders get exposed to the ’70s electronic sounds of Jean Michel Jarre—what he might be spinning on his trusty turntable. Much like his public/private space, Osuna seems comfortable working two different ways at once, more harmonious and connected than conflicted.

Born in Mazatlan, Mexico, Miguel studied and practiced architecture in Guadalajara before switching to fine art and moving to California. He has lived in downtown LA for 12 years and is very much a part of the burgeoning art landscape of the city.

He is best known for his epic landscape paintings that depict vividly colorful scenes witnessed from behind the wheel, in motion: lonely roads, cars on highways, urban architecture and signage, sculptural freeway overpasses. The blurred effect adds abstraction to the representational paintings to create a lost moment in time, a fragment of life that’s gone but preserves on canvas the residual emotional resonance. The work speaks perfectly to the SoCal experience (like Cathy Opie’s small but monumental photos of LA freeways being built) where seemingly all of life happens in cars. Based on images he snaps while driving, he works very quickly with oil paintings materializing in days. You can see his thought processes and inspirations in experiments and studies he has lying around the studio, ideas that will lead to new bodies of artwork. You can also sense his background in architecture in the formal sophistication of forms and structures that populate his canvases.

Miguel Osuma, Frequency Modulated, (detail) pencil on canvas, 2012, courtesy Garboushian Gallery While his paintings are all about the external world, his other body of work is both abstract and existential. He calls this series “Spin,” and like his paintings, these works convey movement but rely on suggestion and motifs. He uses materials from his architecture practice (ballpoint pens, colored pencils, electric erasers) to explore internal and existential subjects, “a theoretical allusion to membranes and particles of energy, this is what I see when I think about the theory of quantum mechanics, that we are all made of particles that are spinning,” Osuna says. Some canvases are literally spun by a homeless assistant he employs part time while the artist drips his paint onto the surface to create an undulating circle. Others are built from fluid but randomly hand-drawn squiggly patterns of ballpoint ink or Prismacolor that cover huge expanses to form dense yet intricate, otherworldly compositions. Another group in this series is created by carefully dropping graphite dust or pigment onto resin while the piece is slowly spinning, the shape created by the centrifugal force, with more light-catching resin layered on top to create a dazzling surface for the organic design.

Like his work, Miguel is always in motion. He’s animated and excited about his next group of paintings for a November show at Garboushian Gallery in Beverly Hills. Currently, he is engineering a curved 35-foot landscape mural he’s painting for a lobby on Wilshire Boulevard and is also working on a commissioned “Spin” piece with his signature calligraphic membranes on many sheets of glass for a collector’s home. It’s impossible not to be inspired by visiting a space spinning with so much creative energy and charmed by the artist working happily in the eye of the storm.

-

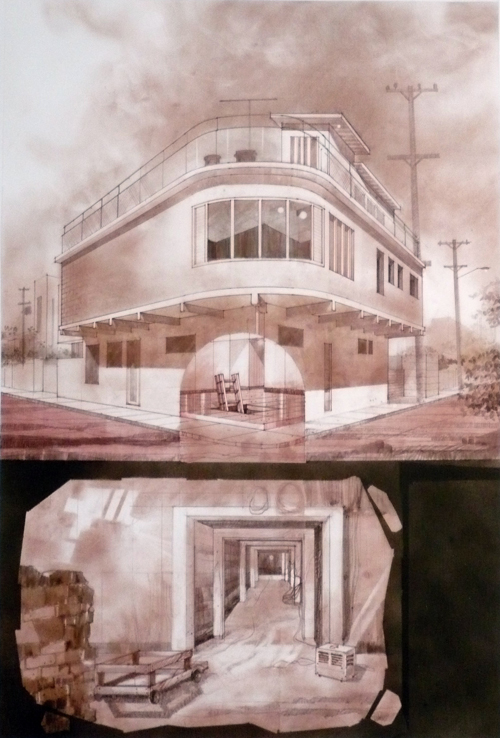

PROFILES: Julio César Morales

Geographical border zones figure prominently in the work of Julio César Morales, particularly those separating the U.S., where he lives, from Mexico, where he was born. In “Undocumented Interventions,” an ongoing series of watercolor and ink drawings, Morales presents a surrealist view of clandestine border crossings, in which piñatas shaped like Barney and SpongeBob Square Pants conceal the hidden bodies of immigrant children, while car seats and stereo speakers mask adults. Objects of consumerist desire become a prison for these desperate people, trying only to survive by making it across. In “Narquitectos,” he diagrams underground border tunnels used by drug smugglers. These makeshift spaces complicate and menace the architectures that conceal them. Though they seem absurd, Morales sources these images from real discoveries by U.S. Customs and Border Protection.