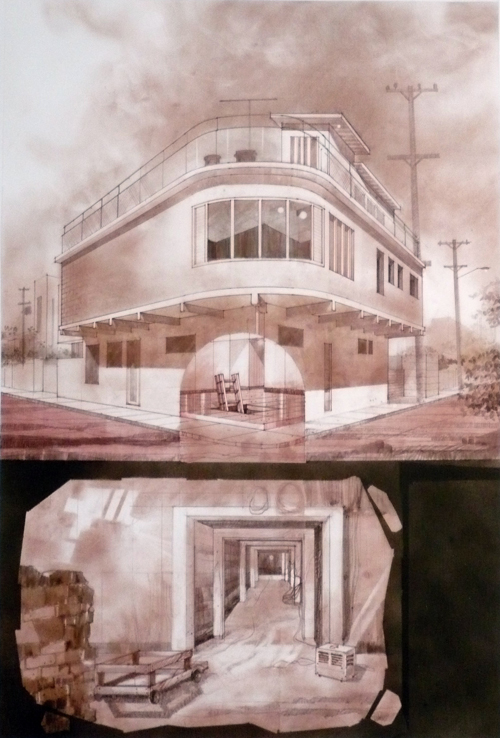

Geographical border zones figure prominently in the work of Julio César Morales, particularly those separating the U.S., where he lives, from Mexico, where he was born. In “Undocumented Interventions,” an ongoing series of watercolor and ink drawings, Morales presents a surrealist view of clandestine border crossings, in which piñatas shaped like Barney and SpongeBob Square Pants conceal the hidden bodies of immigrant children, while car seats and stereo speakers mask adults. Objects of consumerist desire become a prison for these desperate people, trying only to survive by making it across. In “Narquitectos,” he diagrams underground border tunnels used by drug smugglers. These makeshift spaces complicate and menace the architectures that conceal them. Though they seem absurd, Morales sources these images from real discoveries by U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

His approach to interdisciplinary borders is equally permeable. Like his subjects, he goes where the work is. Shifting between curating, teaching, making art and making music, Morales is a frequent collaborator on performance and video projects with Eamon Ore-Giron, and programs San Francisco gallery Queen’s Nails Projects with Bob Linder. Morales’ art also operates in the social realm, as when he and chef Max La Rivière-Hedrick create dinners centered on the extensively researched cross-cultural history of a menu, inviting guests for both a meal and a story.

Julio Cesar Morales, Undocumented Interventions #1, 2011, watercolor and ink on paper, courtesy of the artist

As a curator, Morales brought his global conscience to bear at San Francisco’s Yerba Buena Center for the Arts until this past year, when he joined Arizona State University Museum in Tempe, as curator. “The first project about to open is an amazing show working with the Jumex collection that can have a profound impact in the current cultural climate in Arizona,” he says. Artists from both sides of the border are included—Doug Aitken, Sam Durant, Francis Alÿs and Miguel Calderón. In the long term, he is concentrating on building an archive of Latino video art at the museum. “This new program I am developing serves as a mirroring effect—I am working to develop the largest Latin American video archive in the U.S., housed in the city most threatening to Latinos in the U.S. This juxtaposition reflects the ongoing struggles between the U.S. and Mexico, and their parasitic need for each other.” Morales promises to energize ASU’s student body through his innovative approach to curating and to pedagogy. Given the rancorous rhetoric in Arizona on the subject of immigration, entering the fray seems a characteristically bold move for him.

Asked about the effect of these changes, Morales replied, “Well, I can say that I only have two jobs now—curating and making art! I have had five jobs in the Bay Area for the last 12 years so in a way it’s what maybe being ‘normal’ is like? Far from conventional, being calmer has given me more strength to approach art-making in a new light.” His art is always formally and conceptually rigorous, addressing political realities with clarity and without easy messages. Morales rejects hierarchies amid the formal and informal economies depicted in his art, working instead to depict all participants as equally human.