When I drove up to Zackary Drucker’s home off San Fernando Road, the front door was wide open—a startling sight since most of the surrounding houses have metal bars over the windows and doors. The Los Angeles video and performance artist lives in Glassell Park, an industrial strip in Northeast Los Angeles. Besides the open door, the house also stood apart with its manicured lawn and the polished wood floors I glimpsed through the doorway. It was as if Drucker’s house was in color, and the rest of the neighborhood in black and white.

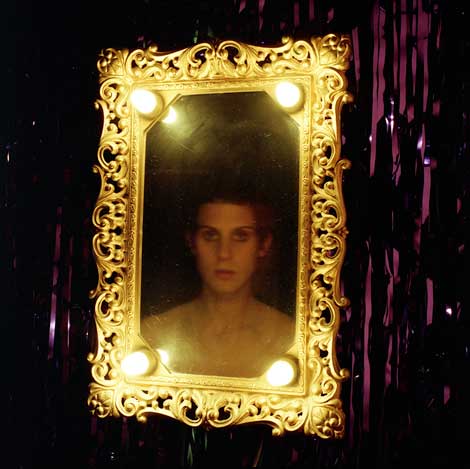

Drucker welcomed me with open arms. We’ve only met a few times socially at art functions, but that’s just how she is. The house is immaculate, though she explains—as if apologizing—she has recently moved in and the decorating was not quite finished. The empty walls are freshly painted in dark grays, browns and puce. Drucker also is dressed in neutral colors wearing a white T-shirt with snug pants, showing off her slim figure. Drucker is a natural beauty, with blond hair and a devilish smile—like she’s got something up her sleeve, but in a harmless way. Her deep-set eyes are so blue they practically sparkle. She invites me to sit down at the round, smoky glass dining room table for our conversation.

In walks Rhys Ernst, her partner in love and art, casually dressed, equally as attractive as Drucker with boyish good looks—not a far cry from the likes of Justin Timberlake. He asks me what he can get me as we all settle at the table. I know their time is precious, as they are preparing for the Whitney Biennial. They squeezed in my promised only-an-hour-of-your-time to meet on a recent Saturday, as both of them work during the week. Evenings and weekends are when they make art, and now it’s spent preparing for their show in New York. They both say to me, nearly simultaneously, “Take your time.”

Zackary Drucker, 30, and Rhys Ernst, 31, both graduated with MFAs from CalArts—Drucker in 2007, Ernst in 2011. They are a transgender couple, Drucker a transwoman and Ernst a transman, meaning Drucker is man-to-female, and Ernst, female-to-male. (The irony of this transition really never comes up.) The new photographs they’ll be showing at the Whitney will illustrate their stages of transitioning and is a body of work they’ve been working on for five years now. Both are artists in their own right, but they often collaborate, and the work being shown at the Whitney is a fully collaborative series. Ernst is known more as a filmmaker and Drucker, a performance artist who works in video and photography. But to be so definitive, so “boxed in”—a phrase that repeats throughout our conversation—would be a falsity, practically a lie. These artists make art out of their daily lives, and that is what their new work will come to reveal. I am instantly drawn into their world, their realm, the moment I sit down.

Drucker and Ernst’s series of photographs will debut at the 2014 Whitney Biennial, along with their film, She Gone Rogue, first shown at the Hammer in 2012 in the Los Angeles biennial, “Made in L.A.” It was that film that captured the attention of this year’s Whitney Biennial co-curator, Stuart Comer. Drucker and Ernst showed him some photographs that have never been seen before. Drucker tells me Comer “knew what was on the table, and what was possible.”

Seeing what was possible could be an understatement—if Comer was also seeing for the first time what I’m seeing. Drucker and Ernst showed me a stack of photographs, the kind you get from the drugstore photo department. They were working proofs culled from five years of taking pictures of one another. At first glance, thumbing through, they look like a lot of selfies—if they weren’t photographs. All the images seem to be exclusively Drucker and Ernst. The photos were taken between 2008 and 2013, basically their entire time together as a couple.

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING

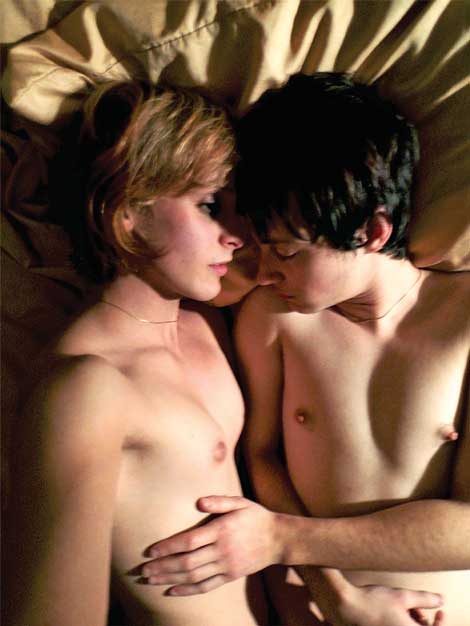

“I think I knew that there was something really compelling there,” says Drucker of the time she started making these images toward the beginning of their relationship. “And it wasn’t until these years accumulated that we realized that there was this incredible archive that really captured the essences of a relationship.” Ernst points out also in their collaborative short, She Gone Rogue, “There is some resolution/revolution to our relationship in the film too, even though it’s very much like a meta-fiction film piece. There’s a fiction/documentary line that we like to play with. This becomes the photographic back story to the film.”

The new series of photographs is aptly called “Relationship.” Drucker has always indulged in self-indulgence—that is obvious if you’re familiar with her sometimes campy, sometimes very serious videos and collaborative photographs, where she’s the lead in almost every scene. So it’s no surprise that documenting their lives while living their lives was a constant in their relationship. “At the time, I was feeling a diaristic impulse towards my own life,” Drucker says. “I would call it a life collaboration. We weave in and out of a creative space, a personal space, and all the lines converge with us.” Ernst adds that a lot of their collaboration is spontaneous, or even routine, like when they’re just sitting around in the evening, “It’s late at night and we like to be creative.”

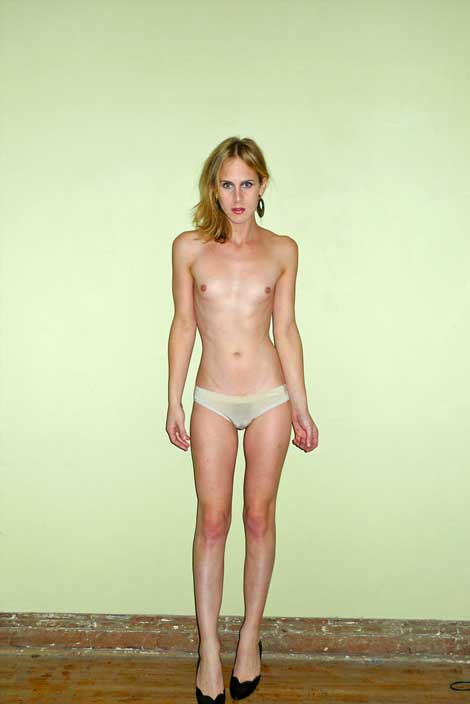

In “Relationship,” their ages would be mid-20s to their early 30s. Five consecutive years in this age range might show a change in appearance. Typically, men get a little more manly, and women get a little more womanly. But in Drucker and Ernst’s cases, it’s a bit skewed. At that particular time and period, they were also transitioning. So it’s more like Zackary Drucker becomes more womanly, and Rhys Ernst becomes more manly.

Seeing the proofs didn’t nearly do justice to the finished photographs when I got a chance to see some of them (albeit digital)—it was like in living color. These were far from selfies. These are of the fine craft of art photography with an edge, with hints of Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, and maybe a little Cindy Sherman. But more honest and raw—I know, how can you get rawer or realer than Larry Clark? I think the reason they stand apart is they are truly collaborative work, and neither Drucker nor Ernst were posing for the camera or necessarily planning a body of work. They were just doing what most artists do—making art. As with any artist, everything one does, essentially, can be called art. So, they were just sittin’ around, being creative, but mainly they were experimenting, documenting and throwing their love around. And that’s the difference.

“Relationship” is a love story. But it’s also an intense time in life for the both of them. They were transitioning, and at the same time. They were essentially going through puberty together. And we see in these photos that innocence, that wonderment, the playfulness. These powerful images allow the audience to be privy to a private world, but we also feel invited. We see Drucker and Ernst early on in their relationship where we are pretty sure Drucker is a male and Ernst a female, though they both have an androgynous look to them. Ernst may be lying in bed, looking like a tomboy with full-on armpit hair. Drucker confronting the camera with only sheer underpants and underdeveloped breasts. Ernst in a field of flowers, clasping a plucked daisy.

“Relationship” boldly exposes and reveals that androgynous period of Drucker and Ernst’s life, that time of what Ernst referred to as “being in the middle,” before they both started taking hormones. We see the subtle changes: more hair and muscle on Ernst’s arms, Drucker getting breasts and smoother skin. Although some of the images may be a bit staged, where clearly the subject is performing for the camera, it really never comes off that way. It’s like stumbling upon someone privately preening for the mirror. Both of these artists show their artistic chops with supreme awareness of technical possibilities, allowing the photos to radiate with their honesty and openness.

WHEN HE WAS A SHE

Ernst grew up in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. His mother was a painter and his father a professor of Islamic Studies. They traveled a lot in his youth, especially in Southeast Asia. He lived in Pakistan as a kid. He dropped out of high school when he was 14. He was into music, had a darkroom and painted—all at age 13. He was a girl then. ”I came out as like gay or queer or something along those lines. I was pretty iconoclastic as a young teenager. I just wasn’t really fitting in—ya know, the round hole, square peg. I got my GED at 16 and started taking college classes early.”

At Hampshire College Ernst got into filmmaking because of its many components, “it was visual, it was writing, it was music. I started doing animation, I would score my own films. My first films were mixed media, kind of more auto-ethnographic.” He then worked in TV in New York, then made his way to CalArts.

At CalArts he studied Film/Video. He immersed himself in the narrative film style, learning all he could about the technical and professional tools of the trade. That, coupled with his TV experience, puts him a notch above other film and video artists. He’s very modest and uses those tools to his advantage, but knows when to back off as well. His filmmaking demonstrates a trained eye, stylish and understated. In his Indie film, The Thing—his MFA thesis which also premiered at Sundance in 2012—one of the main characters is a transman, but nothing is said about it and actually you wouldn’t even think about it or even notice. Ernst says, “For my work, at least, I am very intentionally not underlining it, and often somebody being transgender is very incidental to all these other things going on, it might be the least complex or noticeable thing that somebody’s transgender. So that’s what I really utilize; that it’s just one part of a much more complicated story.”

Ernst is conscious of a transgender population’s ability to disappear, with the capacity to completely pass forever. “That was something I was aware of before I transitioned, and I thought long and hard about how I wanted to make myself visible through my work as a transperson and not hide behind that façade of being transgendered.”

WHEN SHE WAS A HE

“I don’t have any artists in my family. So it was never a familiar trajectory or path or anything that I saw for myself,” Drucker says of growing up in Syracuse, New York. Her family has always been and is supportive of her lifestyle and in fact frequently can be seen in her photographs and films. The only art experience in her past she can think of is when she had her parents take Polaroids of her dressed up in her mothers’ old prom dresses and dance costumes. She made a book out of the pictures.

That experience must have had some profundity as she went on to the School of Visual Arts in New York for her BFA. She took pictures à la Cindy Sherman and explored different female personas and identities. “At that point I was an androgen, always,” she says. “Definitely trying to walk the line. The way I would describe it is I always wore a minimal amount of makeup and usually a low heel. I started testosterone blockers at age 21 or 22. When I started to enter my second puberty was when I really realized I didn’t want to be aging as a man.

“And then that really kicked in after Rhys and I met, which was when I was 25. That’s when I was really making photographs. At CalArts I started making video and performing for the camera. I started a photographic project with Flawless Sabrina, my muse and mentor, archetype, best friend.” (Jack Doroshow, a.k.a., Flawless Sabrina, is the empress of New York drag queens and the subject of the 1968 documentary, The Queen.)

After CalArts, Drucker continued to concentrate on videos, collaborating only with select people, who she continues to work with: Van Barnes, Flawless Sabrina, A.L. Steiner, her mother. A lot of her performances and videos stem from writing—narration is not uncommon in her films. Drucker sounded proud of her accomplishments and jokingly added about one film, “I think when I showed that to Rhys, he really crushed out on me.” She sheepishly giggled, checking with Ernst if that was okay to say. He smiled, it was.

POST RELATIONSHIP

Drucker and Ernst have such an easy demeanor and are respectful toward one another. You can really see how effortless it might be for them to make art together. Both artists have a collaborative element to their art process—Ernst being a filmmaker, by nature a collaborative discipline. Drucker is represented by Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, a gallery in the Culver City arts district. Her last two shows were collaborations with photographer Amos Mac and most recently with London photographer Manuel Vason. Drucker, more immersed in the fine art world, has more of an exhibition record, while Ernst works in the film industry and also does freelance editing.

Both talk about the importance of addressing transgender issues in their art, but admit it could be a subject they might grow out of someday. “It’s not the conversation I want to be stuck having for the rest of my life,” says Ernst—though, “It’s always going to be a part of my lens and I like to think that that meaning will become more and more embedded and less explicit and more implicit. Obviously I don’t want to be pigeonholed by it, but to ask another artist to abandon their orientation as a feminist or of color. I just hope the conversation gets more complex and we don’t have to.”

But what happens when you assimilate to a point where you “pass” and it’s really not even an issue anymore? Do you walk away from that life, and don’t look back? Is it like graduation? Drucker takes on my query: “It’s a conundrum of the trans community in that it is an evaporating community in a way. It’s like a group of people that are able to assimilate into a binary world and have no acknowledgment of their transgender history. And that happens a lot, more than anyone thinks it does, because people are able to assimilate real effectively.”

“What it really means to me is gender freedom for everybody. A lot of transgender people can look at how transgender people can live their lives and be themselves and find the middle space, or whatever that is, and it’s emancipating for everybody who lives in a binary box,” says Ernst.

“We’re preparing for a future generation and also laying the foundation the same way that our predecessors have laid the foundation for us,” Drucker says. “A lot of what I’m interested in is my own history, my own kind of counterculture history, or the history of transwomen, drag queens, gender outlaws. I think that we’re doing necessary work. And we’re contributing to that rich history of perseverance, of determination, or creating our own narrative.

“It’s a new conversation,” Ernst concludes. “And we very much think of ourselves and our audiences as existing in the future. I think we aim to create work that will withstand the test of time, and that isn’t a didactic impulse that we have about teaching people this is who we are and what our lives are. It’s a little more streamlined.”

All images courtesy of the artists and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles

See Drucker and Ernst’s work at the 2014 Whitney Biennial in New York, Mar 7–May 25; whitney.org