We are in a time of global pause. A moment where everyone for the most part, is by mandate, confined to their interiors, forced into slower, humble domesticity; those with children are responsible for lessons, many are taking up culinary endeavors, and for the ambitious, some home projects. With very little chance for public presentation—save dressing oneself for afternoon strolls around the neighborhood with precious little dogs—it feels as if suddenly the world has been propelled into the traditional feminine.

In looking through photos friends share of their long, amorphous days lounging in their homes, I’ve been reminded of scenes rendered by Frederick Childe Hassam, The New York Window (1912) comes to mind, Joven Decadente (1899) by Ramon Casas, really anything in a room by Wyeth. If we find ourselves hungry for complementary images of women in repose, art can lift up its hoop skirt and reveal a bounty of paintings over the centuries. And because of this, and the conditions in which we’ve found ourselves, I’ve returned to the book by French philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space and what he calls “the imagination of repose.” In “House and Universe” he notes for Baudelaire, for the dandy, for the opium-eater, interiors are a chance for “an artificial paradise”—Bachelard writes, “if while reading we accept the daydreams of repose it suggests… it soon brings tranquility to body and soul. We feel that we are living in the protective center of the house in the valley. We too are ‘swathed’ in the blanket of winter.”

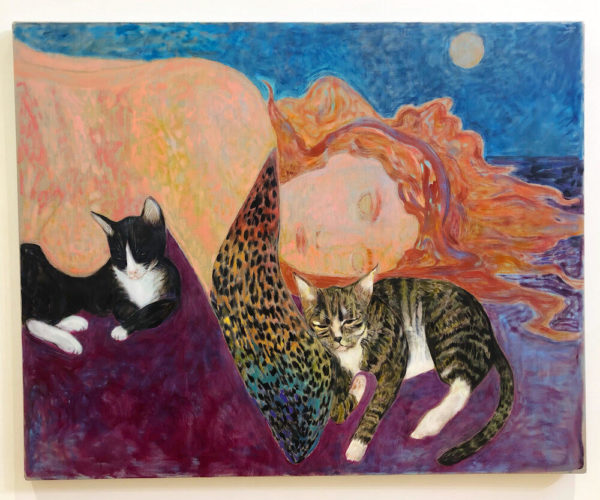

The River 3. 22.25x 20.25,” (2020). Oil on linen. Courtesy the artist and Bozo Mag.

Repose here offers a balm, a comfortable space in which to dream, opium-induced (if we’re lucky) and decadent; repose is, I would say for men, the comfort and allowance of an invisible mother, to lounge and to think and create as one pleases.

But repose is, and has always been, more charged for women.

Hayley Barker is an LA-based painter, raised and educated in the Pacific Northwest, gaining well-deserved attention recently. Her first solo exhibition is upcoming at Shrine NYC this fall. When I visited Hayley Barker’s studio in late January, pre-pandemic, we spoke about just this. Can a woman ever really rest?

Barker taps into the implicit, frenetic energy of the classical female pose—how precariously they sit—and through her splendid use of color and brushstrokes, all the activity of sitting still. One feels the energy of a clenched toe, a bent leg, as the figures maintain their position.

One of my favorite paintings of hers, River 3 (2020) features a nude female figure in the foreground, seated on the trunk of a tree at the water’s edge; the rest of the work is distant cliffs, waves, and leaves—a Romantic’s Eden. The figure has her arms up, to precariously rest her elbows, a diaphanous robe slipping down across her lap; her gaze is demure as her head turns down fixed on her one foot dangling just above the water’s surface. The combination signifies the Classical woman—nude, posed for viewing, in nature—and yet, what prevents her from sliding down the rock if not tight muscles, hyper-vigilance, or the cleverest detail of all, the figure’s finger poking into the side of the tree?

What instantly compels the viewer in Barker’s oil paintings is color. She employs a pastel palette with flourishes of neon; these electric hues enlivening idyllic scenes from our art historical repertoire plunge us into anachronisms—what could be a field for Roman goddesses is now rendered with colors that remind us of the byproduct hues from labs and factories, from man’s clever creation-as-destruction—deadly, poisonous and alluring. I commented on her use of radioactive color admiring the atomic sherbet and chemical-leak lime: “It’s as if a bomb has just gone off or will. These could just as easily be impending doom or post-doom.”

Barker confirmed the intense feminine anxiety embodied in the figure in River 3 and her work as a whole. I asked her if she found the word apocalypse in relation to this charge in her work, a ridiculous term, or rather a male term, something too external; my feeling is that many women exist in aftermath. That the “bomb” is really our own experience with our bodies—moving through sexual assault, miscarriages, endometriosis, hysterectomies, giving birth, orgasms and aging. She agreed, and we laughed for a moment that women don’t need alien invasions, explosions and martial law in a dystopian downtown to feel destruction at bay; writing this in April, I would add, nor do we need a pandemic. Barker said her work involves addressing and healing from trauma, but healing is not calm, and should not connote placid faces and banal serenity. Barker is intent on capturing the chaos of integrating both painful experience, and the illumination born of inner work and spiritual practice.

Swimmer, 20.5″ x 25″ (2020). Oil on linen. Courtesy the artist and Shrine Gallery, NYC.

Considering this, the anachronisms of her work move beyond aesthetic play and serve to capture experiencing time in a new way, or rather, a way that rings truer. I asked Barker if we might indulge a term like “female apocalypse,” and if so, did she feel it existed outside of an isolated event: was the female apocalypse ever-present? Barker expressed, what matters most is the fluidity of time for women, made more apparent when set against nature, as the beautiful must also contain complicated things, violence and disorder, so in this way: it is happening, has happened, will happen at once.

Because the lounging figures in Barker’s work appear active, they command our attention. Like Matisse’s Interior with a Young Girl (Girl Reading) (1906), we witness their interior world spilling over, and radiating out. But with Matisse’s figure, I feel separated from the girl, that what is being radiated from her is—if not veiled from us—still very quiet; Barker’s figures are here to have us look and let us know; they are in radical opposition to the derisory epithet I hear all-too-often of women who are “too much.” Barker told me, personally she is embracing this phrase, inviting in her shadow self, and allowing being “‘too much” to serve as a kind of superpower. Thinking back to Barker’s Bozo Mag exhibition in 2017, and the series of faces she showed, I was reminded of one titled Extra.

The concept of being a little “extra” means embracing the very qualities women have long been shamed for: loud, indulgent, commanding of space. In the world of social media exchange, it might be an image of Rihanna walking down the street with an oversized wine goblet or Maria Callas as Medea with the caption “mood.” Being extra is about being monstrously female and reclaiming it. Considering this, it is of no surprise that Barker is influenced by Kristeva. Barker’s drawings especially are about embracing the monstrous. As Julia Kristeva’s 1980 book The Power of Horror opens:

There looms, within abjection, one of those violent, dark revolts of being, directed against a threat that seems to emanate from an exorbitant outside or inside, ejected beyond the scope of the possible, the tolerable, the thinkable. It lies there, quite close, but it cannot be assimilated. It beseeches, worries, and fascinates desire, which, nevertheless, does not let itself be seduced.

In 2017, Barker, in collaboration with LA gallery Bozo Mag, published a book of Bed Drawings: Dark Goddesses, Queens, and Swamp Things a companion publication to her “Open Studio” Exhibition. The book contains eight 6-inch drawings, black marker on paper, all done, as the title suggests, from bed. Barker explained how important this morning ritual is to her art. To work in the early hours, in the same spot she sleeps, to grasp onto a liminal state a little longer, recall dreams, and revive the images is both therapeutic and generative. For Barker, and for women, the bed, perhaps the greatest symbol for intimate space, is not “swathing us” in rest in comfort from the outside, but a space for confronting and plunging psychic depths and claiming whatever surfaces, in this case compelling and horrific and lovely monster faces. The abject made manifest.

“Some Shade,” 25″ x 20.25,” (2020). Oil on linen.

In Barker’s painting, The Next Time You See Me… (2019 Oil on Linen) we behold a grotesque profile, blue eye fixed at us, hooked nose, sour bottom lip, and wild cotton-candy hair. The title, I think, is a threat; that the phantoms return, that the next time we might we might appear unrecognizable as we tiptoe towards assimilating our complex feelings of attraction and revulsion to our most hidden parts. Barker, as if reading my thoughts completes the title’s ellipses: “…I Will Be 1 M Times More Beautiful.” The greatest threat of all: monster metamorphosis and the concealed shadow of beauty.

As the world outside coughs up another clever meme on “Waiting Out the Apocalypse” and laments the unbearable restlessness of rest, I keep returning to Barker’s paintings and thinking about the homeless, frenetic energy of a human body staying still.

I called Barker this week, to congratulate her on her online group show with Shrine NYC , “Connections,” and to ask if anything has shifted in her practice with the recent stay-at-home orders.

She said, “the realm of the intimate, of self-reflection, psychological states; the relationship with oneself and with other women, the earth and art history is finally on the radars of others. One result is there more appreciation for the subject matter. The world, forced to go slower, is more tuned into notions of healing from trauma. There is I feel, a broader relevance to my work.”

The stunning paintings of Hayley Barker reimagine the woman in repose. This time she has embraced the terror of pre-doom and post-doom and rests, not as a retreat, but as a radically deliberate act: as one radiating triumph in stillness.

Hayley Barker: https://www.hayleybarker.com/